“You will forgive me for saying that this controversy does not interest me or my people.”

Nez Pierce Chief Richard Halfmoon to Yale University Press director Chester Kerr after being asked to comment on whether Columbus or Leif Erikson ‘discovered’ America at an autograph party for a book on the Nez Pierce, quoted in Harry Gilroy, Book Club Picks the Vinland Map, New York Times, November 25, 1965.

Painting by Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze. Secretary of State William H. Seward successfully negotiated for the United States to acquire Alaska from the Russian Empire. Seward House Museum in Auburn, New York.

The purchase of Greenland was considered by the United States government for both strategic and economic reasons long before U.S. President Trump’s recent offer. The earlier proposals were more appealing because of the U.S. public’s excitement, encouraged by a series of popular frauds, about early connections between Norsemen or Vikings and the discovery of the American continent. The 2019 suggestion by President Trump of purchasing Greenland differed from earlier proposals. Not only did the government of Denmark dismiss the proposal; it was completely and rather noisily rejected by the Greenlanders themselves, who today have an autonomous status within the Danish Commonwealth and are working to develop independent nationhood. In light of the recent events, however, it is interesting to examine the history of Greenlandic-American relationships and how important even a fictional cultural connection can be.

For most Americans, a common immigrant background can be a tie to a remote shared past, reinforced by viewing artifacts from other ancient civilizations in museums, through historical programs or movies depicting popular renderings of a mythological time.

Detail of book cover, Leif the Lucky by Ingri and Edgar d’Aulaire, 1941, Beautiful Feet Books; Illustrated edition, October 1, 1994. This children’s book introduced hundreds of thousands of American children to its version of the Viking discovery of the American continent.

In their own way, each experience lends historic legitimacy to awareness of that heritage and enables us to identify with peoples who lived long before the arrival of immigrants to the U.S. from around the world.

One popular connection is through stories of the Norse colonization of the Americas during the Viking age. Stories of Icelandic exploration and the failed colonies of Greenland enriched great medieval literature: the Grænlendinga Saga, the Saga of Eric the Red, and other monumental epics of Iceland. A lesson learned even then was that history would acclaim the chieftains with the best poets (who also served as ancient public-relations men), not necessarily the ones who actually won the battles.

Six to seven hundred years later in the U.S., enthusiasm for ties between America and the Viking settlers of Greenland has produced significant historical scholarship and archaeological excavation – as well as infamous hoaxes such as the Vinland Map and Kensington Runestone.

The Viking discovery of North America was popularized in the U.S. by the very successful children’s book Leif the Lucky by Ingri and Edgar d’Aulaire, published in 1941 and still in print today. Leif the Lucky was followed by over a dozen other children’s and young adult adventure books by various authors built around the discovery, and by the introduction of the visual trope of the Viking warrior as a youthful, muscular, horn-helmeted but otherwise scantily clad hero rather than an aging Wagnerian tenor. (The horned helmet trope was actually invented by a costume designer for the first production of Wagner’s “Ring Cycle” in 1876.)

Detail of “What’s Opera, Doc?” lobby card. Source: Warner Bros. Pictures; a small portion of the commercial product. The image illustrates the dissemination of a cartoon image as a popularizing mechanism for the visual trope of the ‘Viking’ horned helmet. Copyrighted image, Warner Bros. Pictures.

On U.S. television, political contests were the hidden subtext for battles against evil in which the Vikings were inevitably the good guys. It is possible that current U.S. leaders watched episodes of The Ruff and Ready Show as youngsters in 1958, in which a Viking boy named Olaf aids Ruff and Ready in preventing the theft of Professor Gizmo’s secret scientific knowledge by a Cold War-style evil opponent.

The themes of both U.S.-Viking heroic partnerships and stories of how aliens founded earth’s civilization have thoroughly penetrated today’s popular culture. Most recently, they both appear in the cinematic mega-hit adventures of Thor and the Avengers. All of these are elements of a continuing, well-accepted mythology of identity between Americans and a Viking past.

Viking History and the Americas

U.S. fascination with Greenland owes much to these popular and romantic notions about the Vikings. The seafaring exploits of Eric the Red, his son Leif “the Lucky” Ericson, and grandson Thorvald are among the best-known pieces of Viking-lore today. However, although the colonization of Greenland and establishment of several failed settlements in ‘Vinland’ in present-day Canada represent the furthest western reach of Viking settlement, they were outliers, virtual wilderness explorations that had almost no political impact compared to the far greater Viking impact on Russia, the Byzantine Empire, or the lands that form present day Germany, France, Ireland, or England.

Two family sagas of the thirteenth century, the Grænlendinga Saga and the Saga of Eric the Red formed the pre-archaeological basis for the history of the settlement of Greenland and discovery of North America. (In 1070, the archbishop of Bremen also mentions that Danes and Finlanders knew of an island in the ‘western ocean’ at the extreme end of the known world.)

The real history of the Greenland Viking colony is both brutal and relatively short. In 984 C.E. the Viking chieftain Eric the Red was under two sentences of outlawry (skoggangr, a form of banishment), one from Norway for manslaughter and another three-year banishment from Iceland.

Eric found several fjords on the island’s south-western coast with sufficient land for settlement and limited herding. Cleverly naming the prospective colony Greenland, despite its ice sheet and chilly climate, he gathered about 500 settlers from what was then an overcrowded Iceland. The sea journey was perilous; only eighteen of their twenty-five boats survived.

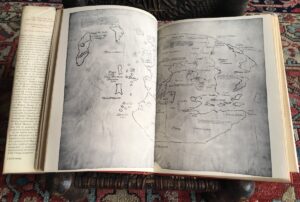

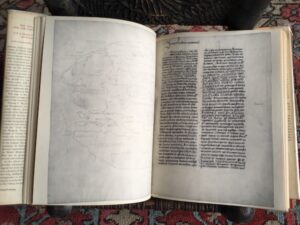

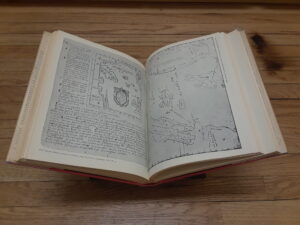

R.A. Skelton, Thomas E. Marston, and George D. Painter, The Vinland Map and the Tartar Relation, The Vinland Map, Yale University Press, October 11, 1965

When Eric the Red established his Greenland colony in about 985, there were no other people living there, its earlier Inuit inhabitants having migrated back to Canada during this relatively warm period. Most of Greenland was too cold and barren to sustain grain crops or raise European cattle, but the settlers grew what they could, supplementing their meager diet with whale, seal meat and fish, growing herbs and hardy vegetables like kale and too often, having to slaughter their cattle and sheep herds for food in the harsh winters. The settlements’ primary economic sustenance was through trade with Iceland and Norway for furs and ivory from arctic animals. Until the late 14th century, while Norwegian kings ruled the Scandinavian region, and until the mini-ice age of the same period, the Greenland colony remained a viable trading post.

In about 986, when a Greenland skipper and companion of Eric’s, Bjarni Herjólfsson was driven far west on a journey from Norway to Greenland, he sighted a region that seemed far richer in trees and animal resources (probably Newfoundland), which he called Markland or woodland, and then an island covered with rounded rocks (probably Baffin Island) before he journeyed clockwise back to Greenland and reported what he had seen.

About the year 1001, Eric the Red’s son Leif Erikson arrived in Greenland, bringing the Christian religion to the country (and upsetting his father, a confirmed pagan). Learning from Bjarni of the land mass about a thousand miles north and west of Iceland, Eric bought the skipper’s boat, hired part of his crew and sailed out to see if this unnamed land might serve as a new base.

R.A. Skelton, Thomas E. Marston, and George D. Painter, The Vinland Map and the Tartar Relation, back page of the Vinland Map and first page of The Tartar Relation.

On arrival in Newfoundland, Leif and his crew set up a small camp with a hall and workspaces. The area was rich in the essential timber resources that Greenland lacked and had much salmon and game. Even better, as they discovered after Leif’s foster father Tyrker reeled joyfully out of the forest, they found fruits they called ‘grapes’ (but which were more likely squashberries, gooseberries or cranberries) that could be brewed into wine. On this expedition, the Vikings found the country entirely uninhabited.

Leif returned to Greenland, gaining his sobriquet “the Lucky” when he rescued a group of shipwrecked Greenlanders en route. He intended to return to Vinland but was prevented by the death of his father Eric the Red and the need to take over the running of the Greenland colony.

Vinland exploration continued as a family endeavor, however. A second expedition was led by Leif’s younger brother Thorvald. This expedition encountered Native Americans. Following a policy of violence first, talk later, the Greenlanders killed eight of the nine Native Americans they found at a landing place. One escaped and returned later with reinforcements. Thorvald died, wounded by an arrow after a series of skirmishes. The remaining Norse returned to Greenland to report that the new lands were inhabited by hostile ‘Skraelingers’ or screechers.

R.A. Skelton, Thomas E. Marston, and George D. Painter, The Vinland Map and the Tartar Relation, Illustration XVII Sigurdur Stefansson, Map of the North, ca. 1590, Royal Library, Copenhagen, Yale University Press, October 11, 1965

In 1009, another effort to establish a settlement in Vinland was headed by members the family, including Freydis, an illegitimate daughter of Eric the Red. The group sailed to Leif’s original “booth” in Newfoundland. The settlement divided after the first winter with one part moving to a new site to build a stockade. This time, when they encountered Native Americans, a friendly trade relationship in foodstuffs was attempted. For unknown reasons, perhaps because the exchanged foods, which were likely primarily dairy-based, actually sickened them, the Indians returned a few weeks later and attacked in force. The settlers barely survived the attack. Freydis, who was pregnant, was a woman of very strong character. She is said to have rallied the Greenlanders and frightened off the attacking forces by shouting like a berserker, pulling out her breast and striking it with a sword dropped by a fleeing man.

This site was abandoned after another difficult winter. A final attempt at settlement at Leif’s booth led by Freydis and two Norwegian brothers failed due to a violent Icelandic type of family blood feud. (Freydis herself organized the killing of the women of the other party.) This was the last attempt known to establish a permanent settlement, although short term expeditions continued as late as 1347 in order to obtain timber for Greenland.

The Greenland colonies themselves were doomed by the lack of resources and of organized government as well as the arrival of the Black Death. It appears likely that Greenland’s Norse population died out entirely between 1500 and 1540.

Archaeological Evidence

In the early 1960s, archaeologists Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad located a Norse site at L’Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland. It may have been the location of Leif’s booth, or else a repair station for ships.[1] These initial finds, though of great importance, have not been supplemented by later excavations. Research at a promising site at Point Rosee, identified through satellite imaging by archaeologist Dr. Sarah Parcak of the University of Alabama, proved unrewarding. Initially thought to be a place where bog ore could have been roasted by Norse visitors, Dr. Parcak’s report concluded that there were no signs of Norse settlement at Point Rosee or clear evidence of human occupation before 1800. Memorial University archaeology professor Barry Gaulton said his colleagues had been doubtful from the beginning, citing the “scanty evidence” that led to the study. Canadian archaeologist Martha Drake concluded that, “There wasn’t one thing that you got to say, ‘Oh boy, that’s interesting.'”

Despite the desire of some American immigrant populations to find a northern European origin story to match that of Columbus, there was almost no immediate or lasting connection between the brief Viking explorations and the Americas. However, the Viking episode did inspire a number of archaeological frauds promoted by both passionate believers and hucksters.

Fictions and Frauds

In the 19th and 20th centuries, wishful thinking and active imaginations have helped to craft a variety of legends connecting the Vikings to the founding of American colonies – and even to the legend of the White God of Mexico, Quetzalcoatl and the founding of Aztec civilization.

The Kensington Runestone on display in Alexandria Chamber of Commerce and “Runestone Musuem” and Alexandria, Minnesota, USA, Photo by Mauricio Valle, 23 February 2018,

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

A 200-pound stone with a supposedly runic inscription dated year 1362, known as the Kensington Runestone, was said to have been discovered in 1898 by a Swedish immigrant, Olof Ohman. Ohman claimed to have dug it from under a large tree in the township of Solem, Douglas County, Minnesota. A University of Minnesota professor of Scandinavian Languages received a copy of the inscription and immediately declared the stone a forgery. A group of Scandinavian historians and linguists followed suit. The so-called runes actually appear to be related to modern Swedish.

Nonetheless, Hjalmar Rued Holand, a Norwegian-American historian and cherry-farmer in Wisconsin, took it upon himself to bring the stone to public attention. He took the stone to Rouen and presented it for study at an international conclave of scholars where it was roundly dismissed. Holand persisted and managed to get it displayed as a national monument in the Smithsonian Institution in 1948, but it was later quietly removed as an embarrassment.

The Vinland Map is the most famous of the likely hoaxes that enshrine the American history of Viking exploration. What excited the interest of scholars in the map was that it showed land west of Greenland labeled “Island of Vinland discovered by Bjarni and Leif in company.” Another legend detailed a visit to Vinland in the last year of Pope Pascal’s pontificate (1117-1118) by an “Eric, Bishop of Greenland.”[2]

A Spanish-Italian dealer of ill-repute named Enzo Ferrajoli de Ry sold the map to American manuscript dealer Laurence C. Witten, who then offered it to Yale University. Collector and philanthropist Paul Mellon agreed to purchase the map for between $250,000-300,000 and to donate it to Yale if it could be authenticated and if Yale would prepare a supporting book.

The Yale Press book, The Vinland Map and Tartar Relation appeared on October 11, 1965, the day before the annual Columbus Day celebration, stirring not only hard feelings among Italian Americans, but apparently resulting in fisticuffs between Italian American and Norwegian American clubs in Brooklyn, New York.[3] John La Corte, president of the Italian Historical Society, stated immediately that, “We are going to put Yale University against the wall.”[4]

Harry Gilroy, Book Club Picks the Vinland Map, New York Times, November 25, 1965.

The map was an untitled pen and ink drawing on a thin parchment, bound together with a manuscript text of the 1245-1247 mission of Franciscan Friar John de Plano Carpini to Tartary known as The Tartar Relation. However, even the first examiners of the documents noted problems with both its content and condition; the Vinland map showed Greenland as an island, when at the time the map was created and for long afterward it was thought to be a peninsula. The map had other cartographic anomalies not found at the time it was supposedly created. Although both documents had wormholes indicating antiquity and were bound together, the holes did not match. A short time later, however, in what some scholars termed ‘a miraculous reunion,’ a third document, Vincent Beauvaise’ Speculum of History, was found, which had the same size parchment and identical wormholes as the map, which it was thought to have been bound to at one time.

A Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice , Michael A. Musmanno, wrote his own book in 1966, entitled, “Columbus WAS First, characterizing Yale’s announcement as “an outright gratuitous sneer at Columbus.”[5] Many tests and historical analyses of the map later, the general consensus of researchers is that while the parchment is fifteenth century, the map itself is not authentic.

Yale University has now chosen not to take an official position on the authenticity of the map. Recently it has been subjected to additional testing including reflectance transformation imaging, or RTI, at Yale’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH). Yale’s stated goal is to better determine the relationship of the map to two medieval volumes that it was found with.

The overwhelming scholarly opinion is that the map is a forgery. In March 2019, Raymond Clemens, Curator of Early Books and Manuscripts at Yale’s Beinecke Library, has stated that the map is clearly a 20th century fake,[6] based both on the testing done over time and on the map’s content, which replicates mistakes found on a printed facsimile from 1782 of Italian mariner Andrea Bianco’s 1432 map, but not on the original.

Buying Greenland – Not Actually a Joke

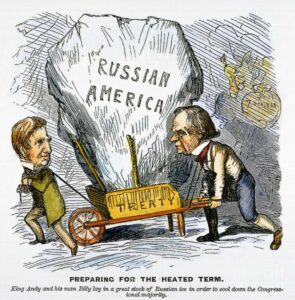

“Preparing for the heated term; King Andy and his man Billy lay in a great stock of Russian ice in order to cool down the Congressional majority”; Pres. Andrew Johnson and Sec. of State William Seward carrying huge iceberg of “Russian America” in a wheelbarrow “treaty”; refers to Seward’s purchase of Alaska in Dec. 1866. Wood engraving. Published: 1867. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-61346

The current U.S. President’s recent suggestion to reporters that he was interested in buying Greenland has raised the island’s profile in the U.S. Questions soon followed: “What?” and “Why?” and “Who exactly does the president intend to buy it from?”

Perhaps a sentimental vision of Viking warrior heritage was one factor behind President Trump’s recent suggestion to reporters that he was interested in buying Greenland. In the past, this wishful history co-existed with a more practical desire to get American hands on a strategic base with rich mineral resources.

Denmark’s Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen, rejected the suggestion as an “absurd discussion” because, as she said, “Greenland is not Danish. Greenland belongs to Greenland.” As a result of the tiff, the President’s planned diplomatic visit to Denmark was cancelled. After NATO allies were critical, Mr. Trump had harsh words for them as well.

Greenland is not an independent country, but its political history subsequent to the Viking era is complex. In the early 17th century, although the Norse colonies on Greenland hadn’t been heard from in 200 years, the amalgamated state of Denmark-Norway still claimed Greenland as part of its Norse inheritance. In 1721, the Danes sent a missionary, Hans Egde, to teach whatever Greenland population might exist about the Reformation that they had missed. Egde found Inuit instead of Norsemen. Nonetheless, he set about establishing a mission and recolonizing the island. Danish merchants followed in his wake and retained tight monopolies on commodities and trade.

After the breakup of the crowns of Norway and Denmark in the Treaty of Kiel in 1814, Denmark ceded the entire territory of Norway to Sweden, but continued to hold Greenland, Iceland, and the Faeroe Islands. After Norway gave up its rights, Denmark attempted to recolonize southwestern Greenland, with limited success.

Despite Denmark’s claims, the island’s ownership remained disputed. Under an early principle of international law, “nobody’s land” or terra nullius, may be legally acquired simply by a state’s occupation of it. (The term terra nullius was frequently applied to lands already occupied by native peoples such as Greenland’s Inuit, who were not considered capable of exercising sovereign rights).

The arctic peoples, whose lifeways were better adapted to the cold and to limited land resources, had made a better job of settling Greenland. Today, people of Inuit heritage form over eighty percent of the island’s population and Greenlandic, or Kalaallisut, an Inuit language, is the island’s official language.

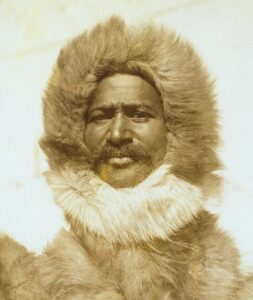

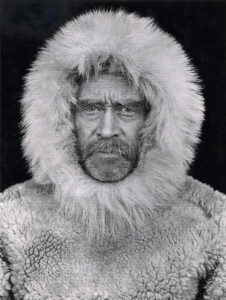

Matthew Henson, American explorer, 1910. Henson was chief assistant to Peary on all his explorations since 1887, his translator (Henson learned Inuit language), and expert in Inuit survival skills on Peary’s 1908–09 expedition to Greenland. Henson was one of the six men – including Peary and four Inuit assistants – who claimed to have been the first to reach the geographic North Pole. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Collection, digital ID cph.3g07503.

Rear Admiral Robert Peary (1856-1920), American explorer, who claimed to have reached the North Pole in 1908. Self-Portrait, Cape Sheridan, Canada, 1909, gelatin silver print, courtesy Christie’s, public domain.

Nonetheless, the American explorer Charles Francis Hall was claimed to have very briefly occupied north-west Greenland in the early 1870s, whereas Denmark’s first settlement in the region was in 1909. Admiral Robert Peary claimed much of northern Greenland after his journeys there in 1909. Peary wanted Greenland both for its strategic military advantage and to prevent other nations from establishing bases there that could threaten the U.S.

President Trump’s offer is not the first time that a U.S. administration has sought to buy or to claim rights over Greenland. In 1867, the same year in which he negotiated the purchase of Alaska, William H. Seward commissioned a report on the purchase of both Iceland and Greenland. In 1946, after the Second World War made plain the strategic importance of Greenland, Secretary of State James F. Byrnes offered Denmark $100 million in gold bullion to transfer Greenland to the United States.

The Danish public reacted very negatively and Danish politicians made the point that the question of selling Greenland was not about money but was based upon the Danish peoples’ identity with the Norse who had settled Greenland a thousand years before. Instead, Denmark demanded that the U.S. recognize her claims to Greenland to secure an agreement for the U.S. purchase of the Danish West Indies, now the U.S. Virgin Islands of St. Thomas, St. Jan and St. Croix.

For almost seventy years, U.S. military have operated in Denmark under the 1951 Defense of Greenland: Agreement Between the United States and the Kingdom of Denmark. The treaty gave the U.S. almost complete authority within “defense areas” set by agreement with NATO. It was under cover of this treaty that the U.S. developed plans in the 1960s for building 2500 miles of tunnels and launch sites for medium-range nuclear missile silos in Greenland’s north, without informing the government of Denmark. Project Iceworm was abandoned in 1966 after it became clear that the glacier through which it was being built was not stable and was moving far faster than anticipated, collapsing the tunnels already built. Nuclear and chemical waste from the project, which was fueled by a portable reactor, was left buried beneath the ice – permanently, it was thought. Climactic changes and rapidly rising temperatures now make it likely that the camp’s toxic waste will be exposed before the end of this century.

Although definitely in agreement with Denmark’s Prime Minister Frederiksen that Greenland is not for sale, many Greenlanders have expressed a strong preference for retaining close ties to the U.S. Greenlanders know their country’s strategic importance and see cooperation with, if not acquisition by the U.S. as resulting in greater security and possibilities for development as an independent nation. Some also see Greenland as a weak political entity that will inevitably be forced to partner with one of the major powers, the U.S., China, or Russia. A U.S. alliance is seen as the least of these necessary evils. Still other Greenlanders are reluctant to relinquish any ties with Denmark, which currently provides the majority of the financial, educational, and medical support for Greenland’s people .

[1] Helge Ingstad; Anne Stine Ingstad (2000). The Viking Discovery of America: The Excavation of a Norse Settlement in L’Anse Aux Meadows, Newfoundland (https://books.google.com/books?id=Gj-I5hdpzGoC&pg=PA28). Breakwater Books. pp. 28–.

[2] Hellen Wallis, FR Maddison, GD Painter, DB Quinn, RM Perkins, GR Crone, AD Baynes-Cope, Walter c and Lucy B. McCrone, The Strange Case of the Vinland Map, A Symposium, 4 February 1974, Introduction by Hellen Wallis, The Geographical Journal, Vol 140 Pt 2, June 1974, pg184.

[3] Id. p 183.

[4] Harry Gilroy, Book Club Picks The Vinland Map: Volume Including Old Chart to Be Book-of-Month Extra, New York Times, November 25, 1965.

[5] Columbus Day Sets off New Discovery War, Chicago Tribune, October 11, 1966, pg A12.

[6] Clemens, Raymond (2019). “Acquisition, Collaboration, Teaching: The Role of the Beinecke Library in Driving Research”. Bulletin of the Center for Historical Social Science Literature, Hitotsubashi University. 39: 13–18. http://hermes-ir.lib.hit-u.ac.jp/rs/handle/10086/30238

Panorama of the island Nunâ east of Upernavik and south of Aappilattoq in Greenland. Photographed south of the island during a sail trip to Upernavik Icefjord. Photo by Kim Hansen, 9 August 2007, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license.

Panorama of the island Nunâ east of Upernavik and south of Aappilattoq in Greenland. Photographed south of the island during a sail trip to Upernavik Icefjord. Photo by Kim Hansen, 9 August 2007, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license.