Euston Station Expansion Requires 45,000 St. James Gardens Reburials

The largest archaeological project ever undertaken in the UK is taking place as part of construction of a high speed rail project that will connect London to the West Midlands by 2033. The HS2 project’s estimated £55 to £106 billion cost is controversial, as is the removal of antique buildings and the disturbance of cemeteries and at least 60 archaeological sites along the route.

Expansion of Euston Station for terminus, photo HS2.

The ongoing expansion of Euston Station in London, a major terminus for the project, will require the reburial of an estimated 45,000 skeletal remains from a former graveyard adjoining the Euston Station site. The graveyard there was used to accommodate parishioners from nearby St. James Church between 1788 and 1853. After laws were passed to prohibit burial inside city, thousands of burials were moved and the area was remade as St. James Gardens, placing stone markers on paths and along its borders. Most burials there were simply covered over, and St. James Gardens is only one of London’s green spaces that was once a graveyard.

Protesters against garden’s destruction wrapped tree trunks in a “yarn bombing” of hand knitted scarves to draw attention to the trees’ fate. Photo source alondoninheritance.com.

Among the famous individuals buried under St. James Gardens are Captain Matthew Flinders, who first circumnavigated Australia, mapped its outlines and gave the continent its name – Bill “The Terror” Richmond, a former slave from New York who came to England and became first a cabinetmaker and then a champion boxer, and political and religious activist Lord George Gordon, who led anti-Catholic riots in 1780. Others buried there include the painters George Morland (d. 1804) and John Hoppner (d. 1810). A memorial to James Christie (the founder in 1766 of Christie’s auction house) still sits in the park, together with memorials to others of his family.

The HS2 project stated that it was working with the Church of England to find an appropriate place for reburial of the skeletons removed for the station expansion. Larger cities in the UK have been dealing with problems of finding space for the dead for centuries. Even mass burials during the Roman period had used cremation and coffining outside of the city and were relatively hygienic, but rules against burials in the city limits were later abandoned.

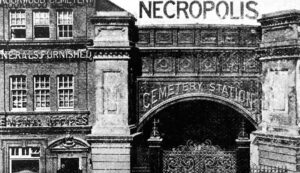

Terminal of the London Necropolis Railway, which ferried mourners and corpses between London and Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey, Image source alondoninheritance.com.

The problem was exacerbated by recurring plagues in which many thousands of inhabitants of London died suddenly, when there was neither time to coffin bodies or adequate space to hold them, leading to mass burials in “plague pits.” Throughout the Middle Ages and into the mid-19th century, burial sites in London were so overcrowded that even recently buried corpses were pushed aside and dismembered in order to accommodate new bodies. The overcrowding of graves led to a foul environment and gravediggers were said to contract smallpox and typhus from diseased bodies. After a cholera epidemic that killed 60,000 people in 1848, the government finally took steps to curb burials in the most appalling cemetery sites in London. The 1850s Burial Acts prohibited all burials in the city except for royalty. Cremation was not made legal until 1885.

Roman Statues in Stoke Mandeville

HS2 Archaeologists excavating the trench where Roman busts were found. HS2

The tracks for the HS2 will pass through the center of numerous small villages; tunneling and construction for the project will require removal not only of additional thousands of graves – but also demolition of both antique and ancient buildings. At the end of October, rescue archeological excavations by the commercial archaeology service L-P Archaeology for the HS2 in England’s West Country led to a remarkable, unexpected discovery on the last day of the dig in the village of Stoke Mandeville in Buckinghamshire.

Lead archaeologist Rachel Wood was excavating a circular ditch around what was thought to be the remains of an Anglo-Saxon tower at St. Mary’s church (c. 1080 C.E.) when the team discovered three Roman sculptures that made global headlines. The sculptures were detailed busts of a man and a woman and the sculpted head of a child, though no body for the child was located. The site also yielded a well-made Roman period hexagonal glass jug, with large pieces intact. As well as the ornate Roman finds, a Saxon coin and Saxon pottery was found at the site.

Roman bust of a male found at St. Mary’s Church excavation. HS2

Archaeologists believe the site to have once been a Roman mausoleum that lay immediately beneath the Norman period foundations. They suspect that the Roman building was deliberately destroyed to build the church as there was no fill between the stone of the mausoleum and church foundations.

Lead archaeologist Rachel Wood holds a Roman bust found in a mausoleum beneath the site of St. Mary's, a Norman church. HS2

Lead archaeologist Rachel Wood holds a Roman bust found in a mausoleum beneath the site of St. Mary's, a Norman church. HS2