How the bronzes became the private property of the Oba of Benin

Plaque, Two Portuguese with manillas, Benin; 16th–17th C, brass, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

In March 2023, Nigeria’s outgoing president Muhammed Buhari issued a Federal Government Order in which he decreed that all “Repatriated Looted Benin Artefacts” including those to be returned in the future will be the private property of the Oba of Benin “to the exclusion of any other person or persons and or institutions.” (See Nigeria Gives Benin Ruler Exclusive Ownership of Bronzes, CPN, April 26, 2023). As the data base Digital Benin shows, the total of Benin artefacts that the British confiscated in the royal court after the conquest of the kingdom of Benin in 1897 and now kept in museums around the world includes over 5,200 items. Buhari’s successor, President Bola Tinubu, congratulated the Oba of Benin on the retrieval of the stolen artefacts during an official reception in July 2023 and pledged the protection and support of the Benin Royal Council in its bid to establish a museum for the artefacts.

All the actors on behalf of the democratic institutions of Nigeria, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Minister of Culture, the Director General of the National Commission for Museums and Monuments as well as the Governor of the Federal State of Edo (with its capital Benin City) have been passed over by this presidential act. Thus, the Benin collections to be returned will not be housed in one of Nigeria’s several National Museums or in a new public museum, the Edo Museum of West African Art (EMOWAA) for which Germany had already confirmed that it would contribute 5 million euros.

In August, President Tinubu announced the appointment of new ministers in his cabinet. The new minister of Art, Culture and Creative Economy is Ms. Hannatu Musawa, a lawyer from Katsina state in North Nigeria; she took a degree in Legal Aspects of Marine Affairs from the University of Cardiff, Wales, and has a master’s degree in Oil and Gas Law from the University of Aberdeen. The new minister of Foreign Affairs is Yusuf Tuggar, the former ambassador to Germany and former chief executive officer of the energy consulting firm Nordic Oil and Gas Services; he has been advocating for more German investment in Africa for many years. As an ambassador, he was also engaged in the discussions on the restitution of Benin Bronzes kept in German public museums. Tinubu and Musawa’s official policies concerning the Benin artefacts transferred to the Oba have not yet been made public. Yet, it seems unlikely that Buhari’s decree will be cancelled, since traditional leaders are also powerful actors in the politics of the republic.

Glossing over history in the name of social justice

Bust of Queen-Mother Idia, Benin, Nigeria, Photo Humboldt Forum, Berlin, Germany.

The impact of Buhari’s Order may be seen in the fate of the 1130 Benin artefacts from German public museums, formerly held as national cultural property, whose ownership Germany had officially and unconditionally transferred to Nigeria in July 2022. The official act of state took place in Abuja in December 2022 when Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock and Cultural Minister of State, Claudia Roth, handed over the first 22 artefacts to the Nigerian Foreign Minister and the Minister of Culture and dedicated them to “the people of Nigeria.” In her speech, Baerbock compared the significance of the bronzes for Nigeria to the writings of the German reformer Martin Luther and the Gutenberg Bible (the first printed book) for Germany. Luther’s texts, which were followed by a revolution (the Reformation), were a protest from the social strata of ordinary people against the highhandedness of the church dignitaries and their selling of indulgences. The Gutenberg Bible is the first printed book and stands for the beginning of letterpress that enabled ordinary people to access religious thought and knowledge in general directly, outside the control of either Church or monarch. Both are potent symbols of successful social movements that finally resulted in the establishment of societies based on principles of egality and democracy).

Ironically, the Benin bronzes stand for the sheer opposite: they are the products of the centuries long slave trade of the Benin kingdom and their rulers. The bronzes were produced by using manillas, imported brass bracelets, for which they traded slaves with the Portuguese, and subsequently with the Dutch and the British. The Benin kings were notorious warriors who raided neighboring villages and regions. Apart from plundering and razing villages to the ground and killing people, they captured men, women and children. They enslaved them and sold tens of thousands of them to European slave traders in exchange for these brass rings. The famous Benin Bronze heads represented royal ancestors and were at the center of the royal cult. The communication with these ancestors consisted of frequent rites in which animals and human being were sacrificed and their blood spilled over the altar with the bronze and ivory artefacts on it.[1] The ancestors bestowed spiritual power on the king and provided him with the legitimacy of rule over his people. Now, transformed into valuable works of art and cleansed of their bloody history of origin, they are being returned to the place of their origin and placed under the exclusive ownership of the descendants of the former slave traders.

Parallels in Restitution – Compensation to slave-holders, not former slaves.

Benin, sculpture of a Portuguese soldier, bronze, photographed by Sailko in the Bode Museum, Berlin, CCA 3.0 unported license.

The way in which slave owners and their descendants are treated testifies to a principle deeply rooted in European history and spread around the world in the course of colonization. History does not repeat itself. Yet the same patterns anchored in the socioeconomic structure of European societies unfold their power again and again: It is not the victims, the slaves, who receive compensation, but the dispossessed slave owners, then as now.

After the abolition of slavery in the U.S.A. and in the French and British colonies in the Caribbean, it was the slave owners who received huge compensation for the “loss” of their slaves. The slaves got nothing. Their reward was “freedom.” They were released into an economic and social void. The plantations and slaves were profit-generating means of production and therefore private property. Thus, the plantation owners, not the slaves, were considered victims.

Private ownership of the means of production is a central building block of a capitalist economic and social order. The transatlantic plantation economy since the 16th century was a driving force in the development of this economy. According to the capitalist logic that emerged in Europe, private property is inviolable. It is under state protection. Private property has even been declared a “fundamental human right” – according to the Declaration of Human Rights whose starting points were European concepts. Private property became, as the French economic historian Thomas Piketty calls it in his book Capital and Ideology, “sanctified.” He shows that this social and economic order, together with its credo, arose as a result of the Enlightenment, the French Revolution and the abolition of the corporate society. Anyone whose property was taken away had the right to compensation. The principles applied to compensating the colonial plantation owners are now being applied to the Benin bronzes.

How slaves bought their freedom

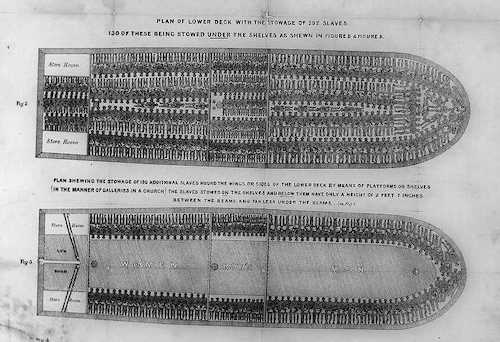

Detail from the Stowage of the British slave ship “Brookes” under the Regulated Slave Trade Act of 178, Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-4400, Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

Haiti is an example of how slave holders – in this case, the whole nation of France – asked for compensation from the freed slaves on an island that had been captured by France and turned into a colony. The slave rebellion in the French colony of Saint-Domingue in 1791 resulted, after bitter fighting, in the declaration of independence and proclamation of the state of Haiti in 1804. It was not until 1825 that France “released” its colony – but under draconian conditions. Haiti was obliged to pay 150 million gold francs – equivalent to today’s value of €40 billion – as compensation for the expropriation of the French plantation owners, an amount representing more than 300 percent of Haitian national income in 1825. Annual interest of 15 percent of national product applied, so it was not until the 1950s that Haiti had paid off the “debt” that was bankrupting the country, not least by clearing almost all of its rainforests for the sale of tropical timber. Investments in the country’s infrastructure were hardly possible.

France has never considered repayment. The post-colonial return of a few sculptures – i.e. symbolic capital – to the Republic of Benin, which was widely announced by President Macron and celebrated as a model in Germany and other European countries, appears in this context to be hypocritical window dressing. Social justice looks different.

Great Britain also applied the principle of protecting private property and thus compensating slave owners when abolishing slavery – in accordance with the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. Evaluation tables were created with the market value of the slaves according to age, sex and productivity in order to achieve the most “fair” compensation possible for the “expropriation” suffered by the plantation owners of their human means of production. £20 million sterling flowed to around 4,000 slave owners.[2] Ultimately, it was the British taxpayers who paid for it. In the United States, the emancipation of slaves and consequent financial losses to slave-holders were factors leading to the civil war between northern and southern states from 1861 to 1865. There has never been redress for that crime against humanity, slavery.

Benin plaque depicting the head of a Portuguese soldier with a background of manillas, brass bracelets used in the slave trade. 16-17th C. Photo by Sailko, GNU free documentation license.

In African slave hunter, owner, and trader societies such as Dahomey (now the Republic of Benin), Ashanti (now Ghana), Benin and the Sokoto Caliphate (both in Nigeria today) – the descendants of the victims of slaver societies have never received any compensation for what was done to their ancestors. This also applies to the descendants of enslaved women, men, and children who, already in pre-colonial times, were trafficked from West and Central Africa via the Trans-Saharan route to the north of the continent and the Indian Ocean. According to the German historian of Africa, Andreas Eckert, around eleven million slaves were deported to the New World between the 16th and the end of the 19th century. Entire regions were depopulated by the “slave production machinery” of powerful kingdoms. Even in today’s African states, descendants of the millions of their fellow citizens who were trafficked to the USA, the Caribbean and Brazil have never been recognized as victims of the slave trade in their country of origin.

None of the kingdoms in which the killing of slaves was institutionalized as a form of human sacrifice in the royal cult has apologized or offered compensation to descendants for the appalling human rights violations suffered by the thousands of people who were murdered. Slavery and human sacrifice were an integral part of Benin’s religiously legitimized social and economic system. When the Benin king, who was deposed in 1897, was already in exile, he asked the British for permission – writes the Nigerian historian Philip Igbafe – to seize some Urhobo slaves and to have them sacrificed in order to put an end to the heavy rains which threatened people and crops.[3]

Repatriation discourse ignores Benin’s history of slavery

After the subjugation of Benin, the British declared the slaves held by Benin chiefs and freemen as free, despite the Benin chiefs bemoaning the economic loss they would suffer. Slaves streamed in large numbers to Benin City, the capital which had been devastated by the British, and celebrated their regained freedom. Fearful of being recaptured and enslaved, many demanded certificates from colonial officials and insisted on paying money for them, as a sort of ransom, analogous to debt bondage, which also existed in Benin.

Igbafe writes that the descendants of slaves continued to be treated with contempt in Benin City until the second half of the 20th century because of their social background. Having been a victim of the rulers of the time is still associated with shame. These victims are not mentioned at all in the elite discourse of the state of Edo, whose capital is Benin City. All those who dare to speak of slavery and the prosperity that resulted from it in the form of the Benin bronzes – or of the spilling of human blood for ritually anointing them – are denounced as liars.

Waist pendant plaque, Benin Kingdom, court style, Edo peoples, Benin City Nigeria 18th century, ivory, courtesy Dallas Museum of Art.

Post-colonial provenance research on the Benin bronzes also only recognizes the slave owners and traders as victims. The true victims go unnoticed; they are literally hushed up, including by German politicians – as is the fact that Africans as well as white colonialists were slave traders and benefited from its evils. It therefore seems grotesque that the “reparation” for colonial injustice – the expropriation of the Benin bronzes financed by the slave trade – consists of “giving back” to the descendants of these despots, who were at the beginning of the chain of the slave trade, their corpus delicti. The political acceptance of the fact that the Benin bronzes from German museums are no longer public cultural assets, but private property of the Benin king, shows how European political actors have internalized the hegemonic and capitalist understanding of property.

The “Benin bronzes” were never the property of the king, which he, as supposedly the only “rightful” owner, could dispose of as he wished, as the European concept of private property would see it. They were not objects, let alone commodities produced for a market and priced by supply and demand. The commemorative heads represented powerful ancestors – they were treated as if they were living persons on whose support the Oba depended for the legitimization of his rule. The king communicated with them, in cooperation with priests and chiefs, with praise and (often human) sacrifices. According to these beliefs, the Oba rose up the ranks of the ancestors after his death to become one of the spiritual masters of his successor.

The reduction of Benin bronzes to their materiality as high-priced art objects which once were held to belong to a private owner and therefore have to be “returned” to him, shows the same pattern that was applied in the “compensation” of the plantation owners dispossessed of their slaves.

Benin bronzes represent the global interconnectedness of people and actions

The Benin bronzes materially and ideally embody central strands of the history of globalization up to the present day. The raw material of the early bronzes came from the Rhineland mining region in the form of brass bracelets called ‘manillas.’ From the 15th century to the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), the German Fugger Merchant Company sold them to Portugal, and from there they were traded to West Africa. Later, manillas from Birmingham and Bristol became the medium of exchange. European traders used the manillas as currency to purchase slaves hunted down by the Benin kings in their wars of aggression in neighboring areas.

Benin bronze plaques displayed at British Museum. Photo Joyofmuseums, 16 July 2018, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Thanks to excellent Benin craftsmen and artists, the mass import of the coveted manillas caused bronze art to flourish, especially the making of relief plates and sculptures. The bronze-casters’ mastery and skill, the victims of war campaigns, the nefarious human trafficking of the African and European slave traders, the transatlantic shipping companies, the slave traders and plantation owners on the other side of the Atlantic and the painful story of the descendants of the West Africans brought to the USA and the Caribbean: all this is embodied in the bronzes. Some of the descendants of the slaves have founded the Restitution Study Group based in New York; they call these artefacts “blood metal” and protest against being excluded from the discussion of ‘rightful’ ownership.

The life course of the bronzes was accompanied by a change in meaning: as the embodiment of ancestors – persons – they were objects of hero and ancestor worship and at the same time, exclusive monarchical insignias of power. Through the British subjugation of Benin, these artefacts lost their sacredness; they became spoils of war, material objects, some of which were thrown onto the art market and sold as world art. They became private property. A large part ended up in museums around the world as cultural assets. There, they were transformed through preservation, research, publications, and exhibitions into what they are today: a first-rate corpus of world cultural heritage.

The Benin bronzes belong to all of us

Cultural assets such as the large corpus of Benin bronzes housed in museums are part of the cultural world heritage of mankind. All those whose actions and suffering are embodied in the artefacts have rights to them. All those connected to them – indeed, all of us – are entitled to know their full history and to acknowledge it. They should also become co-owners of them in the sense of UNESCO’s World Heritage. It is time to give up the exclusive concept of private property– or a single nation’s property – for these cultural assets in favor of a concept of multiple stakeholders. “Shared heritage,” in other words.

Author Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin

Guest author Dr. Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin is professor of anthropology at the University of Göttingen (emerita since 2016). She carried out field work in Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, and Cambodia. One of her main subjects is material culture, cultural property and claims for restitution. One of her recent major publications is: Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin, Lyndel V. Prott, Eds., Cultural Property and Contested Ownership. The trafficking of artefacts and the quest for restitution, 2020, London, Routledge.

A shorter version of this article by Dr. Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin appeared in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) on 6 August 2023 under the title, Der schwierige Versuch, Unrecht zu tilgen.

[1] Mary Lou Ratté, Imperial Looting and the Case of Benin, (1972) quotes from the writings of Felix Roth, a doctor with the 1897 British punitive expedition as follows: “In the king’s compound, on a raised platform or altar, running the whole breadth of each, beautiful idols were found. All of them were caked over with human blood and by giving them a slight tap, crusts of blood would, as it were, fly off. Lying about were big bronze heads, dozens in a row, with holes at the top, in which immense carved ivory tusks were fixed. One can form no idea of the impression it made on us. The whole place reeked of blood. Fresh blood was dripping off the figures and altars...” from Felix Roth, “Appendix II, “A Diary of A Surgeon with the Benin Punitive Expedition,” 1898; Periodical: Journal of the Manchester Geographical Society, Vol 14, 208-221.

[2] According to economist Thomas Piketty, this would correspond to an approximate amount of €120 billion today, i.e. around €30 million, which the state paid to each of these 4000 slave owners. To do this, the national debt had to be increased massively. This “compensation” was paid off until 2015. See Piketty, Thomas, Capital and Ideology, Harvard University Press, 2020, 209, fn12.

[3] “Sir Ralph Moor [the first high commissioner of the British Southern Nigeria Protectorate] reported in 1897 that even after the capture of Benin City by the British, so incomprehensible to the Oba was his surrender, deposition and changed circumstances, that from his jail he asked for permission to send people to Benin waterside to catch some Urhobo slaves for sacrifice as the rains were falling too incessantly for the good of the people and their crops. A woman was usually sacrificed on these occasions with a message for the Rain or Sun god put into her mouth and, after death, she was hoisted on a crucifixion tree ‘for the rain and sun to see’” Igbafe, Philip A. “Slavery and Emancipation in Benin, 1897-1945.”, p. 411. The Journal of African History, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, pp. 409–429

Benin plaque depicting a Portuguese soldier with a background of manillas, brass bracelets used in the slave trade. 16-17th C. Photo by Sailko, GNU free documentation license.

Benin plaque depicting a Portuguese soldier with a background of manillas, brass bracelets used in the slave trade. 16-17th C. Photo by Sailko, GNU free documentation license.