“The Smithsonian has a duty to protect us. We need the Court to stop this transfer or else our children will never have a chance to experience these bronzes. They represent our history, our wealth and the fruit of our ancestors’ labor.” Deadria Farmer-Paellmann, Restitution Study Group, Inc.

Update October 15, 2022

On October 11, the Smithsonian Institution signed an agreement transferring ownership of 29 Benin bronzes to the Government of Nigeria in a private ceremony at the Smithsonian’s Museum of African Art. The Restitution Study Group (RSG), a NY nonprofit focused on slavery justice, had filed a Request for Temporary Restraining Order and Injunction on October 7 to prevent the Smithsonian’s transfer of the Benin bronzes, which were valued at $200 million, to Nigeria.

Judge Christopher R. Cooper the United States District Court for the District of Columbia ordered the Smithsonian, represented by the Department of Justice, to respond to the TRO request.

The Court denied the Restitution Study Group’s request on October 14. RSG director Deadria Farmer-Paellman told the press that the group would appeal: “This is very disappointing, but it is not a reflection of the merits of our case or our ability to meet the procedural requirements. Our papers are well supported with facts and analysis. We don’t have a Court opinion, but the judge obviously did not think this was urgent… the Smithsonian will still need to fight this case in court after that.”

Class Action lawsuit filed against the Smithsonian Institution

Plaque, Two Portuguese with Manillas, Edo peoples; 16th–17th C,

Brass, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

The Restitution Study Group filed a lawsuit[i] on October 7, 2022 against the Smithsonian Institution over its planned transfer of ownership of 29 Benin bronzes from the Smithsonian to the Republic of Nigeria and thence to the Benin Kingdom. The suit accuses the Smithsonian of breach of trust to American citizens, descendants of slaves trafficked by Benin royalty and of acting without legal authority. The suit is an attempt to halt the legal transfer of the bronzes on October 11 from the Smithsonian to Nigerian officials; it seeks a restraining order from the United States District Court for The District of Columbia. This may be the first lawsuit filed on behalf of American citizens of a diaspora claiming a right of access and even to shared ownership of objects from a foreign country as part of their own heritage.

Restitution Study Group’s Executive Director Deadria Farmer-Paellman announced the class-action lawsuit “on behalf of DNA descendants of enslaved Africans from the area known today as Nigeria — 93% of African Americans descend from enslaved people from Nigeria as do 82% of Jamaicans and other Caribbeans.”

The civil suit alleges that the 29 Benin Bronzes being transferred to Nigeria have an approximate value over $200 million and gifting them would unjustly enrich the Nigerian government. It states that “the Benin Bronzes are central to the Smithsonian’s core activities of scholarship, discovery, exhibition, and education and are a vital resource that constitute or should constitute a common law trust for the benefit of descendants of West Africans whom royal Benin traffickers and European slave-traders kidnaped and enslaved.”

In a Declaration in support of the suit, Farmer-Paellmann begins with the example of her own family history to explain the injustice of returning the Bronzes to Nigeria and denying access to descendants of slaves in the United States:

“I am a direct descendent of enslaved people from West Africa. My 23 & me DNA report shows my DNA ancestry at two ports controlled by the Kingdom of Benin during the transatlantic slave trade – Warri and Lagos. The report indicates over 27% of my DNA is from the area known today as Nigeria. My ancestors were enslaved in communities near Charleston, South Carolina – the main port in the United States where people enslaved by the Benin Kingdom disembarked and were sold.”

Deadria Farmer-Paellmann, Director of the Restitution Study Group.

Farmer-Paellmann’s Declaration details an extensive correspondence between herself and Ms. Ngaire Blankenberg, the new director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art, in which she states that Ms. Blankenberg denied a connection between the bronzes and the slave trade. Farmer-Paellmann describes supplying some of the extensive research on which the Restitution Study Group’s data is based, including in Smithsonian publications, detailing the Benin kingdom’s trade in men, women and children in exchange for “manillas” the brass bracelets that served as currency in West Africa. These manillas were also the source of the “bronze” (actually brass amalgams) from which the Benin Bronzes were created.

The Declaration includes multiple exhibits of letters from Nigerian, Senegalese, Canadian and United States researchers into the transatlantic slave trade that provide historical information that Farmer-Paellmann states support the lawsuit’s contentions that manillas were a major form of currency used in the slave trade and that artifacts such as the Benin Bronzes were made from melting down these manillas.

(For reporting on a number of alternative perspectives on the repatriation of Benin Bronzes, arguments by Nigerian factions over ownership, the history of Benin’s slave trade and sacrifice of human captives, see Where will Benin bronzes go? Nigerian government, Edo Museum or Oba? Cultural Property News, October 4, 2022.)

Group says descendants of slave traders should not be the exclusive owners of Benin bronzes.

“Modern” copper alloy (probably brass) manilla of probable early 19th century date and of type ‘Okpoho’, The manilla is in the form of a small penannular arm ring. Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS), A-SA 4.0 license.

Objections raised by African American scholars, pastors, public servants, and nonprofit organizations present fresh insight into arguments for and against returning the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria. They point out that Britain’s destruction of the kingdom of the Oba of Benin in 1897 was not only an example of colonial oppression but that it also ended Benin’s long history of slave trade and human sacrifice. They say that the global appreciation for the outstanding artistry of the Benin Kingdom must also acknowledge that the Benin Bronzes were made from melted down “manillas,” the currency used to purchase human beings for the slave trade for 300 years.

A letter dated September 14, 2022 signed by African-American leaders seeks retention of Benin bronzes in Western museums so that the descendants of enslaved peoples would have access to them.

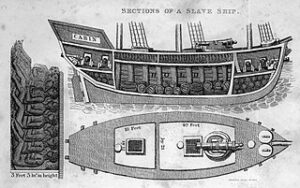

Drawing of a cross-section of a slaver ship in Brazil, from book by Robert Walsh, published 1830.

Professor Raymond Winbush, Director of the Institute for Urban Research at Morgan State University, a Historically Black College in Baltimore, Maryland addressed a petition to the chair and CEO of Britain’s Charity Commission, Germany’s Minister of State for Culture and the Media, and to the director and General Counsel of the Smithsonian Institution. Professor Winbush and other signatories argue that the children of enslaved peoples need equal access to the bronzes.[ii] While they understand the desire of Nigerians to repatriate important cultural property, they also support “the retention of bronzes at Western museums where, due to the transatlantic slave trade, descendants of enslaved people who paid for the bronzes reside.”

The petitioners note that an estimated 1 million people are believed to have been enslaved by the Kingdom of Benin between the 16th and 19th centuries.[iii] Professor Winbush states, “the descendants of the slave traders should not be the exclusive owners. The children of the enslaved need access to them too.” Given that there are an estimated 2,500 and 10,000 Benin artifacts from the period available worldwide, there are enough to be shared and to “bring about healing between both groups.” They support using alternatives to restitution, through the sharing of materials between Nigerian and US, UK and other museums, to educate the public in the historical wrongs of both colonialism and slavery.

Additional reading: Where will the Benin Bronzes Go? Nigerian government, Edo Museum or Oba? African American human rights activists say wherever they are, Benin’s slave trading history must be told.

[i] Deadria Farmer-Paellmann and Restitution Study Group v. Smithsonian Institution, Emergency Motion for Temporary Restraining Order and Preliminary Injunction, Civil Case No. 1:22-cv-3048, October 7, 2022.

[ii] The petition’s signatories were Raymond A. Winbush, Ph.D. Director, Institute for Urban Research Morgan State University Baltimore, Maryland, Dr. Jeremiah A. Wright, Pastor Emeritus Trinity United Church of Christ Chicago, Illinois, Kamm Howard, Executive Director Reparations United Chicago, Illinois, Rev. JoAnn Watson, Former Member Detroit City Council and City Council President Pro Tem, Detroit, Michigan.

[iii] Matthias Busse, “Remelted Slave Money,” in the Sächsische.DE, on August, 29, 2022 Busse.

Beechey, Richard Brydges; HM Brig 'Philomel' Capturing the Slaver, 'Condor', off the Coast of West Africa, 1880 (Midshipman Commanding, Ralph P. Cator); Defence Academy of the United Kingdom; Royal Navy Trophy Center.

Beechey, Richard Brydges; HM Brig 'Philomel' Capturing the Slaver, 'Condor', off the Coast of West Africa, 1880 (Midshipman Commanding, Ralph P. Cator); Defence Academy of the United Kingdom; Royal Navy Trophy Center.