Impelled by digitization and driven by the goal of bringing global access to culture, the concepts of “museums” and “archives” are changing. In an age when many elements of authentic culture and its history can be found online, there are opportunities to preserve history and promote cultural understanding by applying modern technology to age-old issues of cultural survival.

Reclamation and Revisioning for Cultural Survival

The Facebook notification popup said “Rinpoche is live: Day 1 of a two day Avalokiteshvara Empowerment.” The link connects to a live stream of the Tibetan Buddhist Lama in his meditation room. Behind him are Tibetan Buddhist deities in both traditional painted scroll thangka and statue form.

It is morning in India and the birds are singing as monks in face-masks light candles and make offerings to the deities in preparation for the empowerment, a ritual that confers the qualities of the deity onto the participants, in this case, the compassion of Avalokiteshvara. The Lama is reading in Tibetan from a pecha, an elongated loose leaf Tibetan book. This one is a ritual text, likely centuries old, dedicated to Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of compassion. As he chants the text his hands dance between different mudras, gestures that convey enlightened meaning.

Leaf from a “Prajnaparamita” (Perfection of Wisdom) manuscript. The text, written in Tibetan language and script, is a translation of a Sanskrit text that was produced in India as much as a thousand years earlier, 13th C, ink and paint on paper, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, gift of John and Berthe Ford. Creative Commons license.

A camera pans the room and passes two large screens with a few dozen Zoom attendees participating in the preliminary practices of the empowerment. After the Lama concludes, and then starts the teaching, translation in English begins. He occasionally directs his comments to the Zoom participants by name and exchanges warm smiles with them. This ancient ceremony, in practice for over a thousand years, is being conveyed to tens of thousands of people all around the globe.

Also this year, to commemorate Saga Dawa Düchen, the day where Buddha’s birth, enlightenment and parinirvana is celebrated across the world, another Rinpoche, asked his students to create a “virtual choir” recitation of the Heart Sutra that we may “invoke love, kindness, and healing, and open our hearts for the earth.”

The Heart Sutra is perhaps the most well known sutra in Buddhism, recited in temples and meditation rooms all around the globe. A conversation between two disciples of the Buddha, Avalokiteshvara and Shariputra, on the nature of transcendent wisdom, it was translated into Tibetan, in the ninth century.

Over thirty participants in ten different countries each sang the sutra separately. The different parts were then edited into a visual and auditory harmony. The choral arrangement was by a New York based multidisciplinary music and theater artist, Harry Einhorn whose work has been deeply inspired by Tibetan Buddhism. The Nalanda Translation Committee, an early Tibetan to English translation group founded in the 1970s, composed this English translation of the Heart Sutra.

When completed, the video was globally broadcast via Zoom, YouTube, and Facebook.

Pre-COVID, people would travel to hear these Lamas teach and to receive their blessing. Now the Lamas can reach thousands of people in the comfort of their own homes and their direct students can attend via Zoom. As the first reflected, he has been able to catch up on his rest since the global pandemic halted his arduous travel schedule and still be able to teach.

The live-streamed empowerment and recitation above highlight how elements of Tibetan culture have become integrated into world culture with people who are not ethnically Tibetan but who identify as Tibetan Buddhists and with Tibetan culture, creating a kind of meta-Tibet, now connected through the Internet.

While these are doorways to dharma and Tibetan Buddhism in the digital age, and contribute to the preservation of aspects of Tibetan culture, they are not the living and changing culture itself, in situ, in Tibet.

Historical Background

What is recognized as Tibetan culture today is rooted in the snowy mountain landscapes of the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau, grounded in indigenous cultural practices such as those of the Bön, and infinitely influenced by the teachings of Buddhist masters from the great Indian centers of learning like Nalanda, and Vikramashila.

There have been multiple Tibetan dynasties controlling large portions of Central and East Asia since the seventh century. At its height, Tibet included almost two million square miles and portions of the countries that are now China, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Bhutan. In about the eighth century, Buddhism became the state religion, and with the “Great Fifth” Dalai Lama in the seventeenth century, the Dalai Lamas assumed control as both the spiritual and temporal heads of Tibet. They would maintain this control, even within the Tibetan Government in exile, until the current Dalai Lama completed the investiture of his temporal powers in a democratic system in 2011.

“Commentary on the Profound Inner Meaning,” a core treatise by Karmapa 03 Rangjung Dorje, 1615. Buddhist Digital Resource Center, BDRC. Currently, the BDRC has placed over 11,000 Buddhist texts available for online viewing.

In a move to modernize China and transform it to an industrial economy, Chairman Mao Zedong’s Army invaded Tibet in 1950 to remove what Mao saw as a feudal system, and to force negotiations for control. By the end of 1959, close to 100,000 Tibetans had fled Tibet. Thousands more followed in subsequent decades, relocating around the globe. In the years of the Cultural Revolution, over 6,000 monasteries were destroyed, their libraries burned in large bonfires. Monks and nuns were imprisoned, tortured, and killed. The devastation caused by the Chinese invasion, a famine that lasted through 1961, and the Cultural Revolution that finally lost its momentum in 1976 with the death of Mao, resulted in deaths of over a million Tibetans.

When restrictions began to loosen on religious and cultural expression under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, and after the Third Plenum of the Eleventh Chinese Communist Party Congress in Beijing in 1978, Tibetans began a careful dance of reclamation, adaptation, and preservation of their cultural heritage.

The Chinese government also invested in Tibetan language and culture. By the mid-80s many monasteries, especially in Eastern Tibet, were able to revive their monastic education programs. Some Tibetan Lamas were allowed into Tibet to assist with the reclamation of their former monasteries. Han Chinese patrons and disciples supported many of these efforts. As one researcher noted, there is “a potent belief in the spiritual power of Tibetan Buddhism [among the Chinese].”

Other monasteries, nunneries, and hermitages emerged that were rooted in ancient tradition but not always based in Tibetan Buddhist sectarianism. The largest of these was Larung Gar, founded by Khenpo Jikphun in 1980.

Khenpo Jikphun chose to form what he called a “mountain hermitage” rather than a monastery for a number of reasons. His most frequently stated one, according to David Germano in Buddhism in Contemporary Tibet: Religious Revival and Cultural Identity, was that Khenpo Jikphun saw “the most pressing contemporary need to be the renewal of scholarship and meditation all over Tibet, a task that in his view a new monastery with its inevitable sectarian tendencies could never accomplish.” Larung Gar became a thriving center of Tibetan Buddhist education, supporting thousands of monks and – notably – nuns from across the Tibetan Plateau in their scholastic efforts. In turn the Larung Gar-trained monastics have spread Khenpo Jikphun’s ethos of non-sectarianism widely throughout Tibetan society.

Since the late 1980s simmering discontent with Chinese control in Tibet has led to waves of protests and in response, increased regulation on Tibetan cultural expression by the Chinese Government. Larung Gar has been one institution affected. Though the hermitage has been allowed to continue its education program, between 2011-17 officials have evicted thousands of monks and nuns and enforced other restrictions.

Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche gives thanks to Gene and the new Mac computer over his head that holds 12,000 tests. Production still from the film Digital Dharma by Dafna Yachin, digitaldharma.com. © 2012 Lunchbox Communications.

E. Gene Smith: Setting the Path Toward Digital Dharma

“Every culture is a precious flower that deserves to be preserved and cultivated. It will make us more human.” E. Gene Smith

Gene Smith was a student at the University of Washington in the 1960s when he was introduced to Dezhung Rinpoche, one of 25 Tibetans who had relocated in Seattle. In 1959-60 the Ford Foundation helped to bring members of aristocratic families to the United States. Because these families in Tibet had close ties with the religious establishment some of the new arrivals from Tibet were high-ranking lamas. The foremost of these religious figures was Dezhung Rinpoche of Eastern Tibet. Dezhung Rinpoche was born in 1906. He had the traditional Tibetan Buddhist training of a high lama, and had studied with some of the leading masters of the day.

Smith’s meeting and subsequent study with Rinpoche and other Tibetan religious figures sparked his lifelong quest to assist the Tibetan people in locating and restoring lost texts of Tibetan culture. Smith’s career with the Library of Congress, especially his position as station chief of its offices in India, facilitated access to Tibetan texts that had made their way out of Tibet and into the bookstores of India and surrounding countries.

The 2012 documentary by Dafna Yachin, Digital Dharma: One Man’s Mission to Save a Culture, tells Gene Smith’s story from birth to death. It focuses on his collecting, digitization, and dissemination of Tibetan texts as well as the creation of the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center (TBRC) in 1999. TBRC was created to preserve Tibetan texts – starting with Smith’s personal library – in digital form, catalog them, and make them accessible to anyone with an internet connection or portable hard drive. Shelley and Donald Rubin of the Rubin Museum of Art; Peter and Patricia Gruber of the Gruber Foundation; Richard and Mary Lanier; Linda Pritzker; and the Khyentse Foundation all provided support to launch the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center.

His Holiness shows Gene the only text he had with him when he fled Tibet. Production still from the film Digital Dharma by Dafna Yachin, digitaldharma.com. © 2012 Lunchbox Communications.

In 2015 the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center expanded its mission and, in 2016, officially became the Buddhist Digital Resource Center (BDRC), which has now archived over 15 million pages of Buddhist works.

Unlike the Bible or the Koran, the Tibetan Buddhist canon is not a single book and not so easily portable. In two parts, called the Kangyur and Tengyur, the Tibetan Buddhist canon consists of over 4,500 works in 332 volumes. Because of the sheer size of the volumes of canonic text it was very difficult to travel with them, and most were left behind in the Tibetan diaspora. These texts are viewed as the heart of Tibetan culture and venerated as the speech of the Buddha and other enlightened masters.

The film Digital Dharma introduces many of the Rinpoches, Lamas, and others involved in Tibetan cultural reclamation and preservation from the 1960s until 2012. Dilgo Kyentse Rinpoche was a prominent Lama who promoted Tibetan Buddhism and culture throughout the world. A documentary on his life, Spirit of Tibet: Journey to Enlightenment, The Life and World of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, notes that he was able to work carefully with local governments and Tibetan leaders in the 1980s in Tibet to help restore texts and monasteries there. During scenes of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche’s visit to the only Tibetan printing press not destroyed in the Cultural Revolution, the narrator notes that the press is “no less sacred than a temple” because of the sacredness of the texts it produces.

Over his lifetime Gene Smith acquired an immense collection of Tibetan literature. It became his fervent wish, even in the 1970s and 80s when it was not possible to work in cooperation with the government in China, that his library could be made accessible to the Tibetan people, the majority of whom live in China and in Tibet. In light of that wish, he bequeathed his entire library to Southwest University for Nationalities (SWUN) in Chengdu, China (Now Southwest Minzu University).

On December 16, 2010 Gene Smith passed away. In June of the following year his archive of over 12,000 Tibetan texts, the single greatest collection of Tibetan books outside of Asia, was dedicated as a library at SWUN in his honor.

BDRC, the world’s largest collection of Tibetan Buddhist literature

During a recent interview with CPN, Dr. Jann Ronis, executive director of the Buddhist Digital Resource Center, noted that while Gene Smith’s work and the work of BDRC has been extremely important in the recovery and preservation of the Tibetan Buddhist textual tradition, they haven’t been the only organization dedicated to this mission. “We see ourselves as just one player on the Tibetan Plateau. A lot of the texts that we are digitizing, even without us, would eventually find the light of day.”

“The exposition on the graduated path” by Kadam Master Sharawa Yontan Drak (1070-1141) Buddhist Digital Resource Center, BDRC. The only surviving manuscript of the Kadampa school—a 11th- and 12th-century tradition.

A large part of the cultural economy in Sichuan Provence, China revolves around Tibetan Buddhism and cultural tourism. Shops in Chengdu sell thangkas, statutes, and Tibetan Buddhist texts. There is also an economy around the digitization of these texts with the monastic community driving much of this work. A monastery may unearth a previously unknown text and bring it to a data input center where it is manually keyed into a computer so that multiple copies can be printed. The Lamas edit the book once its entry is complete. The book is then sent to a state-run printing house where the content is approved and the book is given an ISBN number. The Lama or the monastery pays the state to print the book and also pays for the ISBN number.

Though there are many such printing houses and text preservation projects in Sichuan Provence, the BDRC fills a niche that most other digitization programs do not.

In line with Gene Smith’s methods, “Our policy is to ‘Hoover up’ everything we get access to. “ said Dr. Ronis. “We don’t disregard texts because they are so called ‘duplicates’. When it comes to manuscript culture there is no such thing as a duplicate, every handwritten text is unique.” He described how some ‘duplicate’ texts might also have notes in the margin or other variations that add to the meaning. “Even if the title is very common, there is probably some unique feature to the text that should be digitized.”

Because duplicative or familiar texts are not digitized by other researchers and monks, BDRC’s work is essential because their text digitization team is tasked with digitizing works that haven’t been accessed before.

“We also don’t disregard the very local and parochial works” like locally produced rituals and local histories, noted Dr. Ronis. He continued, “If a text is written by a local priest, only for use by the local priests, someone raised 100 miles away won’t know the deities referred to in the texts, or its terminology and idiosyncratic abbreviations. These texts will be meaningless to them in every way. They are not their deities and they don’t even really understand the language. But, if the right person would get hold of the texts, they would absolutely speak to their traditions.” This type of scenario allows a deeper reclamation of regional culture. Such works are also primary materials for in-depth academic understanding.

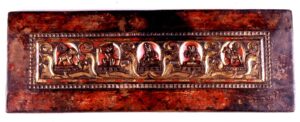

Cover of a Buddhist Manuscript, Tibet, 13th C, wood with paint and gilt, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, gift of John and Berthe Ford. Creative Commons license.

“Tibetan graduate students and professors in Tibet love BDRC” says Dr. Ronis. “It’s safe to say that it would be impossible for someone to write a serious Ph.D., either inside or outside of Tibet, without BDRC, without our material.” He noted that all the classic texts of Tibetan Buddhism have been recovered, but that “BDRC has the variant editions and lesser known works on which dissertations are based. No one else offers such a wide selection of rare Tibetan works.”

If the internet is now a living digital global museum with a mandate to bring history and the objects of history to the world, to discover and integrate the “whole and full and complex truth” in the spirit of reclamation, and in some cases, cultural survival, then BDRC is an integral part of the reclamation of Tibetan culture, through its work of preserving Tibetan writings, a foundation of Tibetan civilization.

In 2016 the Buddhist Digital Resource Center was tasked with a new mission, the preservation and dissemination of all living Buddhist canonical traditions around the world that are endangered due to poor storage conditions, neglect, and precarious social factors. “To this end we recently began an ambitious project in Cambodia to digitize palm leaf manuscripts held in rural monasteries that survived the tumultuous twentieth century.” said Dr. Ronis.

To facilitate its mission and to create increased access to these texts, BDRC launched a sophisticated new website in August 2020. Along with holding the Buddhist texts that BDRC has digitally preserved, the new website is also designed to allow extensive two-way data sharing with institutions. BDRC already has data sharing agreements with the British Library and the SAT Daizōkyō Text Database at the University of Tokyo. As Dr. Ronis noted, two-way data sharing allows BDRC “to amplify the dharma treasures located in libraries and museums around the world.”

With this access to texts in Sanskrit, Chinese, Pali, Tibetan, Burmese, Khmer, and Newari, the possibilities for a deeper understanding of the Buddhas’ teachings are unlimited.

The Broader Goals of Digitization

Book Cover with the Seven Jewels, Tibet, Tsang Province, 1150-1250, wood with pigments and gilding, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, promised gift of John and Berthe Ford. Creative Commons license.

Questions about the nature of a museum, the purpose and the variability of preservation of objects were addressed recently by critic, playwright, and former Trustee of the British Museum Bonnie Greer, writing on ‘The Era Of Reclamation’, project she worked on with Hartwig Fischer, Director of the British Museum. Greer says in ‘three journeys‘ that the project is “The result of a series of conversations that we had, that we are still having, [this] idea of reclamation as a sign of our time.”

“We, all of us, want to take something back; have something back. What that is differs from person to person; from community to community; from nation to nation.” She explains, “Maybe it is our human connection that, above all, we want back, that we need back right now. This includes our ancient connections, as well as the whole and full and complex truth about them. And what better arena for this journey, this conversation, this debate, than a global museum.”

Although Greer was referring specifically to the brick and mortar British Museum, her words also illuminate the aspirations underlying BDRC’s project. The whole internet is now a form of living digital global museum with a mandate to bring history and the objects of history to the world, to discover and integrate the “whole and full and complex truth” in the spirit of reclamation, and in some cases, cultural survival.

E. Gene Smith with monks at TBRC. Production still from the film Digital Dharma by Dafna Yachin, digitaldharma.com. © 2012 Lunchbox Communications.

E. Gene Smith with monks at TBRC. Production still from the film Digital Dharma by Dafna Yachin, digitaldharma.com. © 2012 Lunchbox Communications.