Kathmandu, Nepal Microphones placed on painting hung over table.

Nepal’s Department of Archaeology held a press conference in its Kathmandu offices on March 30, 2025, unveiling three extraordinary examples of Newari paintings. The paintings were taken from the Itumbaha Monastery in Nepal in about 1980 and returned this year by New York prosecutors. The three paintings are more than 500 years old; their description as paubhas identifies them as of Newari heritage. In addition to the three ancient paintings, a number of bronze objects and sculptures and a clay face of Bhairava, a Shaivite and Vajrayāna deity, were included in the display of returned objects. A magnificent sculpture of Buddha Sheltered by the Serpent King Muchalinda, known as the Muchalinda Buddha, from the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, was also displayed by National Museum staffers. This outstanding twelfth century sculpture had been identified through an early photograph by Art Institue provenance researchers as originally in the Guita Bahi, a group of three monasteries in the Kathmandu Valley. The sculpture had been donated to the Art Institute by collectors Marilyn and James Alsdorf, now deceased, in 1999. After researching its provenance, the Art Institute proactively contacted the Embassy of Nepal in Washington, DC to arrange its return.

The story of the three sacred paintings, stolen 45 years ago was very different. The paintings were taken by thieves from the inner sanctum of the Itumbaha monastery, a historic 11th-century site in central Kathmandu. Each painting was only publicly displayed during the Gunla festival. The theft occurred during this festival, with the perpetrators gaining access through a small opening in the wall. The loss was discovered by priests and caretakers the next morning.

Despite the crime being reported to the police, to Nepal’s Department of Archaeology (DOA), and customs at the airport, the official report disappeared following a suspicious fire at the police station. Community members, however, never ceased efforts to locate and recover the artworks.

A 1978 photograph served as key evidence of the paintings’ provenance. In 2003, concerns were raised when replicas appeared during a Smithsonian exhibition. Nepalese community members wrote to the exhibition’s coordinator and government authorities requesting help in halting any public display and initiating repatriation.

By 2006, official confirmation that the paintings had been stolen—not sold—was submitted to Nepal’s Department of Antiquities. Further investigations, coordinated by the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign, involved collaboration with heritage experts, local witnesses, and legal authorities in New York.

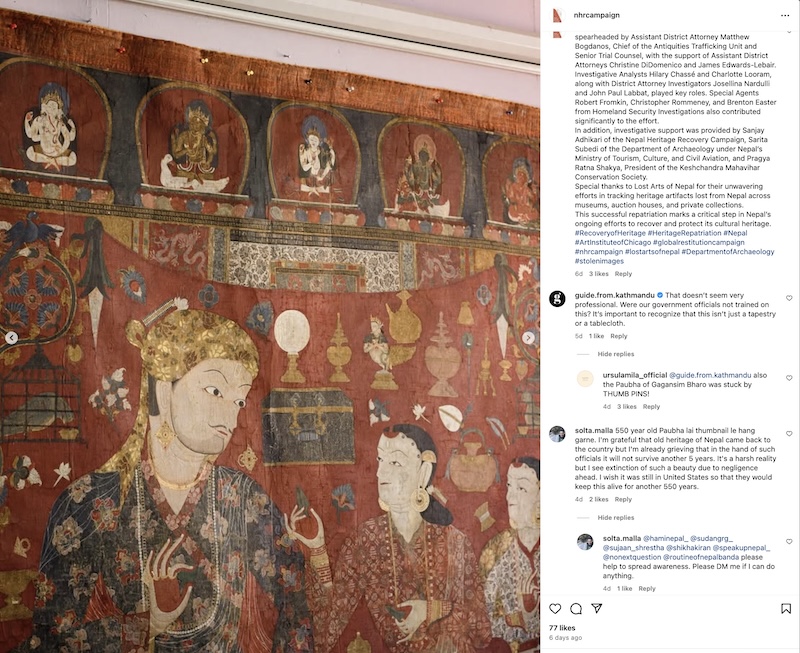

After years of advocacy and legal proceedings, the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office secured the paintings, which were formally handed over to Nepalese representatives in New York. Community organizations, including Newa Guthi, an organization practicing and promoting Newari culture abroad, raised funds to return the paubha and twenty brass and bronze sculptures of deities to Nepal. However, the treatment of the objects during the return ceremony in Kathmandu, seen in press images and videos and shared online, has shocked Nepalese and international viewers who responded with outrage on social media. The artworks appear to have been repeatedly handled in a manner that any cultural specialist should have known was abusive. In one photo, a videographer rests his elbow, holding a heavy film camera, directly on an incredibly fragile ancient painting as he shoots around the room.

After the conference, one of the representatives from Department of Archaeology measured and weighed the paintings before dispatching them to a facility of the National Museum of Nepal, where they will be displayed for three months. This display is also raising concerns as the National Museum is said not to be well-equipped for the conservation of the delicate paintings. Commenters have noted that as a practical matter, the Itumbaha Museum might be better equipped to conserve the paintings at this time. In fact, some suggested on social media that the paintings would have been better preserved if they had remained in the U.S.

After the conference, one of the representatives from Department of Archaeology measured and weighed the paintings before dispatching them to a facility of the National Museum of Nepal, where they will be displayed for three months. This display is also raising concerns as the National Museum is said not to be well-equipped for the conservation of the delicate paintings. Commenters have noted that as a practical matter, the Itumbaha Museum might be better equipped to conserve the paintings at this time. In fact, some suggested on social media that the paintings would have been better preserved if they had remained in the U.S.

The Manhattan District Attorney’s office’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit (ATU) returned altogether twenty artworks to Nepal in March 2025. The ATU’s press release described how the following “key pieces” were seized and returned. Each had been in the United States for between 45-50 years:

“The Portrait of Gaganshim Bharo with His Wives – this monumental pigment and gold on cotton portrait is a paubha, a type of traditional religious painting made by the Newar people of Nepal. Dated by inscription to c. 1450-1474 C.E., this portrait depicts the military governor Gaganshim Bharo performing an unknown ritual with two of his wives. The portrait, along with two other paubhas, was stolen from the Itumbaha Monastery in Kathmandu during a break-in robbery in 1980. They were then smuggled out of Nepal and trafficked through Switzerland before ending up in the possession of a New York County-based antiquities dealer in 1982. In 2003, federal authorities began investigating the theft, but all three Itumbaha paubhas remained with the dealer. Then, in 2024, members of the Nepali community contacted the ATU requesting assistance on behalf of the Monastery. Using extensive in-country contacts and international partners, the ATU conducted its investigation and seized all three paubhās two months later.”

“The Figure of Buddha – Made of black stone, this statue dates to the 9th century C.E. and depicts the Buddha Sakyamuni. The Buddha was stolen from a stupa in Bungamati, Nepal in the late 1970’s and next appeared with a dealer in London in the 1980’s, who sold it to an American collector. After being offered for sale at Christie’s New York in 2015, the Buddha was donated to the University of Michigan Art Museum, where it was recovered by the ATU in 2024.”

“The Stone Goddess – This statue likely depicts the Hindu goddess Parvati or Lakshmi. The Goddess first appeared in a niche in the Vishnu Devi Temple Complex, Kathmandu, in a 1975 photograph taken by the Austrian architect Carl Pruscha. It was next seen in a 1984 shipping receipt recording its arrival in New York County from Switzerland. The Goddess was then purchased by New York-based collector Robert Hatfield Ellsworth and remained in his Estate’s possession until it was seized by the ATU in 2025.”

Kathmandu, Nepal. Tacking 500 year old sacred painting to wall with pushpins. Cropped.

The U.S. nonprofit Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust and the Rubin Museum in New York have been prominent supporters of Nepalese efforts to build expertise in care and conservation of ancient objects in Nepal. A remarkable collaborative effort has resulted in the restoration of the Itumbaha monastery in Kathmandu and the construction of a new, up-to-date Itumbaha Museum to house its treasures and share them with the Nepalese public.

The Itumbaha Museum has a fascinating history. In the 1990s, local Kathmandu residents discovered over five hundred ancient items in very bad condition in a storeroom in an important 11th-century monastery complex in the Kathmandu Valley. They established an organization, the Shree Bhaskardev Sanskarita Keshchandra Krit Paravat Mahavihar Conservation Society, to preserve the objects and developed a plan for the Itumbaha Museum to exhibit them but eventually abandoned it as there was no government funding available. After the 2015 earthquake, the residents contacted the Rubin Museum and asked for its assistance. The Rubin Museum and Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust provided both funding and expertise to enable the conservation and display of the monastery’s long neglected artifacts – enabling the opening of the Itumbaha Museum at the monastery. Throughout, the project was designed and developed by Nepalese, with support from foreign organizations. This museum, though only recently organized, could be be a destination for future returns.

Instagram announcement by National Museum of Nepal and responses.

Instagram announcement by National Museum of Nepal and responses.