Many articles lamenting the loss of India’s cultural heritage have described the suffering of village communities whose ancient statues have been plucked from local temples and smuggled overseas. The villagers’ distress is undoubtedly real – and ongoing. When stolen statues are recovered, they are rarely given back to the villagers to be re-consecrated and replaced in temples. (A pair of stolen statues were in fact returned to their temple, after being discovered in an Indian museum where they had been kept for 50 years – after a judge’s order.) Most often, however, statues retrieved from overseas are neither returned to temples nor put on display in Indian museums. It appears that when cultural artifacts are nationalized, their local ties are weakened. Temple statues may be stolen from the villagers, but once found, they belong to a national government with little interest in returning them to their original homes.

If the old gods are being lost, disappearing into foreign collections or police godowns, where are replacement gods to come from? Major temples can afford to buy newly carved stone idols from sculptors still working in India. In a development which highlights the dual modern identity of Indian religious sculpture as both sacred icons and decorative artworks, some Indian copyists now take orders over the internet for delivery of replicas and works inspired by ancient art around the world, which are pictured with accompanying “artist statements,” as is customary for secular contemporary art.

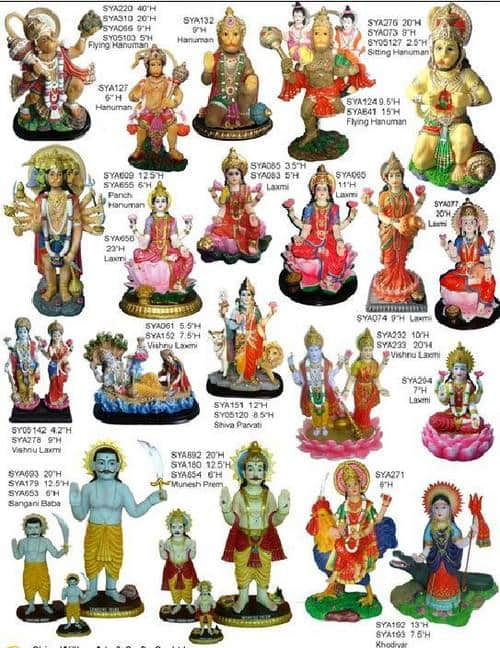

However, many of the newer gods making their appearance in India today are not made in India at all. These colorful polyresin figures, used for household worship or given as wedding gifts, arrive by the hundreds of thousands via container from China each year. Their presence in Indian homes is a reminder that ‘tradition’ and ‘cultural identity’ are extremely malleable concepts. And why not? After all, a static culture is a dead culture.

Amidst the rising tides of isolationism, nativism, and protectionism, the foreign extraction of these new gods is a reminder that a living culture stays alive through exchanges with its neighbors, as well as internal growth and change. This is just one of countless stories of artistic borrowing and trade which go back millennia, showing the inseparability of art and commerce. They also demonstrate how adaptable the concept of cultural heritage can be.

Illustration from Huc and Gabet’s Souvenirs d’un voyage dans la Tartarie, le Thibet, et la Chine pendant les années 1844, 1845 et 1846.

Religious statues, whether made from classical materials or bright plastic, have not always been created by co-religionists. China in particular has a history of participation in the trade in sacred sculpture, described by French Catholic missionary Évariste Régis Huc in the two volume Souvenirs d’un voyage dans la Tartarie, le Thibet, et la Chine pendant les années 1844, 1845 et 1846. Together with another French missionary, Joseph Gabet, and a young ‘Mongolou’ priest convert, Huc made a difficult and dangerous journey through China and Mongolia enroute to Tibet, where they hoped to establish a Lazarite school.

Stopping at Tolon-Noor in Mongolia, they visited a foundry where religious statues were made to order for Tibetan monasteries and temples, and Huc commented upon the workmanship and quick turnaround of the Chinese craftsmen:

“The magnificent statues, in bronze and brass, which issue from the great foundries of Tolon-Noor are celebrated not only throughout Tartary, but in the remotest districts of Thibet. Its immense workshops supply all the countries subject to the worship of Buddha with idols, bells, and vases employed in that idolatry. While we were in the town, a monster statue of Buddha, a present… to the Tale-Lama, was packed for Thibet on the backs of six camels.

We availed ourselves of our stay at Tolon-Noor to have a figure of Christ constructed on the model of a bronze original which we had brought with us from France. The workmen so marvelously excelled, that it was difficult to distinguish the copy from the original. The Chinese work more rapidly and cheaply, and their complaisance contrasts most favourably with the tenacious self-opinion of their brethren in Europe.”[i]

In our 21st century, the Chinese still work very efficiently. A persuasive article in Yale Global Online, Made in China: Millions of Hindu Gods by Dr. Farok J. Contractor, a Distinguished Professor at Rutgers Business School, uses the example of the hugely popular polyresin gods to illustrate the continuing barriers to India’s productivity and resulting trade imbalances between China and India, despite a more than four-fold difference in labor costs (India’s 92 cents per hour to China’s more than $4) and the added costs and time of bringing goods 7,300 kilometers by sea. The output and measures of productivity, however, are five to one in favor of China, so the Chinese costs remain lower. The cost of shipping from Guangzhou to Mumbai is very nearly equal to that of trucking from Delhi to Mumbai, and is just as fast, due to the poor condition of many of India’s roads. Electricity costs are about the same, but India suffers from frequent blackouts and ‘load-shedding,’ deliberate cutting of electricity by overburdened, antique plants.

Strikes and slow-downs are frequent among India’s 16,000 unions, and government regulations make it punitive to have more than 100 employees in any business. While both nations ranked high on Transparency International’s Corruptions Perceptions Index for 2018 (78th out of 180 countries for India, 87th for China in 2018), Dr. Contractor points out that Chinese corruption tends to be high level and infrequent, whereas “bribery in India is petty and frequent,” constantly impeding the process of manufacturing. All these factors helped to keep the trade imbalance for export goods between India and China at six to one in 2016.

These figures are a matter of deep concern for Indian manufacturers, and for the Secretariat of Infrastructure, but for many individual consumers, Chinese efficiency is a blessing.

Chinese manufacturers can boast same-day design and incredible turnaround time to make thousands of statues. The Chinese-made gods have made small home shrines affordable for low wage-earners and even for many of the 500 million Indians earning less than $2.75 a day, who could not afford the ceramic or brass statues made locally. The polyresin statues from China retail for as little as $3.

There can be some cross-cultural anomalies in the Chinese production. Some factories offer a wide range of products for global consumers, including Christian religious figurines and cartoon characters. One polyresin Ganesh, made by the Chinese company Southwell, was advertised as “Religion: Judaism.” More concerningly, Dr. Contractor partially attributes the popularity of the polyresin figures to an increase in the spirit of Hindu nationalism – despite their international origin.

Many Indian brass and ceramic craftsmen facing crushing competition from Chinese producers have abandoned traditional media and adopted their rivals’ materials, making their own polyresin gods, although using more basic techniques. They buy polyresin by the kilo, and hand pat it into molds made, not from Indian models, but copied from the Chinese imported gods.

And what of the art of the craftsman, and the ancient conviction that his work was inspired by communion with the god, or at least deep pious intention? More modern notions have intervened, and wholesalers are marking the gods with brand names to develop customer recognition. Nonetheless, at least one wholesaler of Chinese gods insists, “These holy idols are created in a spiritual atmosphere.”

Another traditional Indian industry, and a commodity as necessary as idols for religious activity, is the incense business, which is also facing severe competition from both China and Vietnam. Indian incense is made by hand, Chinese, more cheaply, by machine, but a rise in duties has helped to keep Indian businesses afloat, even in hard economic times. One Indian manufacturer was quoted as saying, “In troubled times, people tend to pray more and that’s when they need agarbattis to please the gods. So, we are safe.”

This made-in-China story plays out in big ways and in small. The giant, 597 foot tall statue of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, India’s first Deputy Prime Minister, a particular project of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, known as the Statue of Unity, was cast in a foundry in China.

Statue of Sardar Vallabhai Patel, Statue Of Unity, Sardar Sarovar Dam, Kevadia, Gujarat, India. Photo, Prime Minister’s Office of India, Wikimedia Commons.

The fact that Indian gods are now mostly made in China challenges our accepted ideas about what is tradition and what is heritage in several ways.

Switch countries, and take the example of a more ‘traditional’ cultural property conflict, this time between Korea and Japan, that played out in 2013, when South Korean authorities arrested five South Korean men for smuggling two Buddhist bronze statues from Japan. The two statues had been in Japan for over 600 years, on a small island between Japan and Korea. They were from sites associated with the Tsushima temple.

The Buseoksa Temple in South Korea claimed that at least one of the statues had been made there in the 14th century based upon a document found inside the statue. The Japanese asserted their right to the statue on the grounds that it had been purchased from Korean commercial bronze casters, much like the Chinese workmen in the Mongolian factory who so impressed the French missionaries. The future of the statues became a highly contentious public issue, in part because of difficult political relations between Japan and South Korea, and a Korean judge refused to allow the statues to be returned to Japan.

Monks of the Buseoksa Temple in South Korea attempted to achieve a reconciliation with the Tsushima temple in 2013. They arrived, bringing with them three miniature plastic female figures that are sold as the temple’s “mascots” and a newly made bronze statue by a contemporary artist as a symbol of renewed friendship. The monks of the Japanese Kannonji temple were insulted and refused to meet with the representatives.

Was an insult intended? Is this a cultural misunderstanding about the juxtaposition of modern figurines versus revered ancient objects? Two groups of Buddhist monks, whose homelands are separated only by a narrow waterway, not by great lengths of time and space, so misunderstood one another and so differently construed what constitutes ‘heritage’ that they could not even speak together.

[i] Travels in Tartary, Thibet, and China, During the Years 1844-5-6, by M. Huc., translated from the French by W. Hazlitt, Vol. 1, p 35-36, National Illustrated Library, London, 1851.

Polyresin Hindu Gods, Credit: CHINA WILLKEN ARTS & CRAFTS LIMITED

Xiamen, Fujian, China

Polyresin Hindu Gods, Credit: CHINA WILLKEN ARTS & CRAFTS LIMITED

Xiamen, Fujian, China