Archaeologists and Native American preservationists reacted with outrage this Fall when St. Louis based luxury lifestyle magazine Sophisticated Living featured an unusual piece of real estate scheduled for auction under the title “The Ultimate (Man) Cave comes to Auction.” On sale were 43 acres in Warren County, Missouri, “teeming with natural springs, rolling hills, and wonderful views,” complete with its very own “subterranean masterpiece” known as Picture Cave.

Book Cover: Picture Cave: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos, by Diaz Granados James R. Duncan, and F. Kent Reilly III, Alan Cressler (Photographer), Patty Jo Watson (Introduction)

(The Linda Schele Series in Maya and Pre-Columbian Studies), University of Texas Press, June 2015.

Picture Cave houses over 290 of the most remarkable Native pictographs in the United States. The pictographs vary in age from 600 to more than a thousand years old. Archaeological evidence suggests that the cave and similar sites in the region had been used and decorated by Native peoples for thousands of years. Indigenous tribes – ancestors of the Osage Nation and other tribal nations – used natural pigments to paint the walls of the cave with colorful and detailed images of their lives, rituals, stories, and beliefs. The cave system was a place for storytelling and for ritual. Burials of indigenous people took place both in the cave and across the surrounding region, making the land surrounding the cave also sacred to the history of the Osage nation.

On September 15, 2021, the cave and surrounding area was sold at auction to an anonymous bidder who paid $2.2 million for the site. The new owner is a “cave conservationist who wishes to remain private”, according to Bryan Laughlin, director of Selkirk Auctioneers & Appraisers. (See “Truly Heartbreaking”: Osage Nation Decries Sale of Cave Containing Indigenous Art.) According to Laughlin, “potential bidders were vetted to ensure the protection of the ancient artworks.” The recent history of the cave, which has been the property of one family since 1953, includes several known instances of vandalism, and at least one attempted theft of a section of the painted walls. (See the Introduction to Picture Cave: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos, by James R. Duncan and Carol Diaz-Granados). It is only in recent years that gates have been installed over the entrances to the cave to protect the contents. By the time these measures were put into place the floor and walls of the cave had already been extensively impacted by earlier visitors, Investigating archaeologists believe that many artifacts had long since been removed when they began to document the cave’s contents in the late 1980s. The walls are marked in many places with names, dates and other graffiti left by the curious, the earliest dating to 1840.

Picture Cave

The cave lies somewhere in the rolling hills of Warren County, perhaps seventy miles west of the ancient mounds of Cahokia and the modern city of St. Louis. What is known of the human history of Picture Cave comes from the oral traditions of the descendants of the cultures that created the images on its walls, scientific and linguistic analysis, and archeological investigations. This last source of information has been limited by the difficulties inherent in conducting research on private property. Natural obstacles also impede study: the pictographs of Picture Cave lie in a complete darkness that has helped to preserve them to the present day. Access involves crawling for several feet before lowering oneself fifteen feet down a series of ledges to the cave floor. Despite these challenges, it is one of the most intensely researched and ethnologically interesting caves in North America.

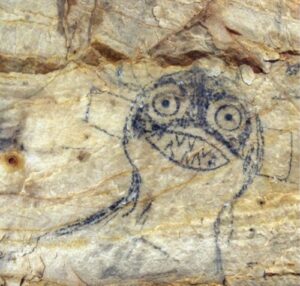

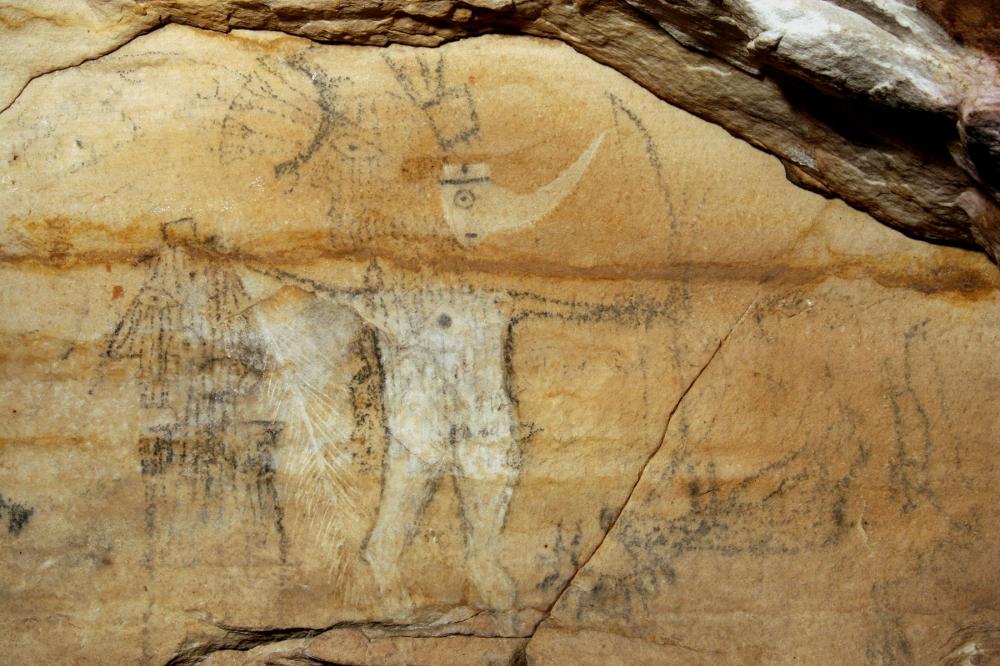

The pictographs, composed of natural pigments in shades of red and black, depict fantastical creatures, supernatural beings, and ordinary daily life. Chemical analysis dates the pictographs in Picture Cave to between about 800 CE and 1025 CE, contemporaneous with the Cahokian civilization. The UNESCO Heritage Site of Cahokia, in Illinois, known for its mounds and intricate artifacts, is thought to have been the largest and most sophisticated pre-contact settlement north of Mexico. There is strong evidence that its cultural reach extended throughout North America, including the region surrounding Picture Cave. The cave art constitutes a key resource for students of the history of pre-contact North America.

Image from Picture Cave: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos, photo by Alan Cressler, source Selkirk Auctions.

The sale of the cave is controversial. Dr. Andrea Hunter, Historic Preservation officer of the Osage Nation, told Jeannette Cooperman in the August 24, 2021 article The Midwest’s Lascaux Is Up for Auction, that “the location of Picture Cave, contains the burials of hundreds of our Osage ancestors and some of our most sacred locations.” While there are some legal protections in place, including both a Missouri law that provides limited protection for burial sites and associated cultural items and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), private ownership of property generally supersedes indigenous rights to access these spaces and practice religious traditions. Despite efforts to educate the public on the importance of sacred sites and cultural landscapes to indigenous people, most of Missouri’s petroglyph and pictograph sites remain in private hands. Two exceptions in the state are Washington State Park in Washington County and Thousand Hills State Park in Adair County, Missouri.

The Osage Nation claims a primary ancestral connection to Picture Cave. In an Osage Nation claim for human remains under NAGPRA for another site, Dr. Hunter and archeologists James Munkres and Barker Fariss derive the contemporary Osage nation’s relationship to the makers of the pictographs in Picture Cave from ‘archaeological data, oral traditions, historical, and linguistic evidence’. The line of descent from the Dhegiha Siouan-speaking tribes who first migrated into the region and settled it nearly two thousand years ago to today’s Osage nation is a long one, known today through oral traditions and historical traces such as the pictographs in Picture Cave themselves.

One research team, lead by spouses James R. Duncan and Carol Diaz-Granados, have spent decades studying the cave, culminating in the 2015 book Picture Cave: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos.

Duncan discussed the significance of the site in a 2008 article by Michael Gibney for the Columbia Missourian entitled Missouri cave paintings give ancient insight, explaining that the evidence of Picture Cave dramatically impacts the current understanding of North America’s pre-history.

According to Duncan, “The figures on the walls of the cave in east-central Missouri now provide crucial details of the prehistoric timeline of the region. And there’s recent evidence that the paintings in Picture Cave predate the Cahokia Mounds as the birthplace of what archaeologists refer to as the Mississippian period.

“According to archaeological records, the Mississippian period saw the creation of some of the first large towns and city centers north of Mexico. The conventional belief has been that this period started around 1050 AD, but the [details of the] drawings in Picture Cave indicate the period began earlier and in a different location.”

While scholars’ interest in the cave is rooted in its relevance to the study of pre-contact North America, for members of the Osage nation the cave is still sacred, part of their living history. Echoing the Osage claim to the cave, Duncan said to New York Times reporter Isabella Grullón Paz after the sale of the cave, “Osage elders have called the cave the womb of the universe.”

The cave’s new owners have promised to preserve the caves from further thefts or vandalism and allow access to Osage tribal members and researchers. In time, thanks to the attention brought to ‘Picture Cave’, the Osage nation may gain stewardship of the area, including its “subterranean masterpiece”.

Image from Picture Cave: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos, photo by Alan Cressler, source Selkirk Auctions. Image identified with the Hočąk spirit Redhorn in the Encyclopedia of Hočąk (Winnebago) Mythology by Richard L. Dieterle.

Image from Picture Cave: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos, photo by Alan Cressler, source Selkirk Auctions. Image identified with the Hočąk spirit Redhorn in the Encyclopedia of Hočąk (Winnebago) Mythology by Richard L. Dieterle.