Papua New Guinea collection, MIssienmuseum, 18 December 2015, photo Kleon3, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Efforts to return ritual skulls collected by colonial missionaries to their place of origin have faced an unexpected obstacle: the modern-day Papuan communities have firmly refused to take them back.

Ritual skulls, crafted by the Iatmul people who live along the Sepik River, were initially used in ceremonial practices. These intricately decorated objects incorporated human skulls as their base. The skulls were taken from the graves of venerated ancestors several years after they had died, then faces were modeled over the skulls in clay. They were central to spiritual rituals, including mourning and invoking favors for warfare or hunting.

The practice of headhunting, intertwined with cannibalism, was a rite of passage for Iatmul men. Warriors collected skulls during battle, boiled away the flesh, and stored them in spirit houses for ceremonial purposes. These objects, once revered in the tribal culture, became highly sought-after collectibles in Europe during the colonial era, symbolizing the perceived “savagery” of the tribes and justifying colonial intervention as a “civilizing” mission. In the first half of the 20th century, villagers began to decorate the plain skulls of decapitated enemies that were hung about in houses as battle trophies as if they were ancestor skulls in order to satisfy foreign market demands.

Taxidermied mammals in Missiemuseum Steyl, Venlo, the Netherlands, 23 June 2017, photo Kleon3, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

In a bid to address colonial legacies, the Missiemuseum (Mission Museum) in Steyl, the Netherlands, recently initiated discussions about returning five ritual skulls to the Papuan communities. The museum, founded by German Roman Catholic missionaries in 1931, holds numerous artifacts collected during missionary activities. The skulls, like many other objects, were acquired as symbols of indigenous cultures and the perceived need for “civilization.”

The Missiemuseum has a collection of literally thousands of ethnographic objects – some displayed in traditional museum format with specific objects highlighted, but with hundreds of others collected in high, deep showcases arranged by country and type. There are ethnographic materials from China, Japan, Indonesia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Ghana, Togo, Congo and Paraguay, sent or brought back over decades by Christian missionaries. The museum is also famous for its extraordinary collections of taxidermied animals, insects and butterflies.

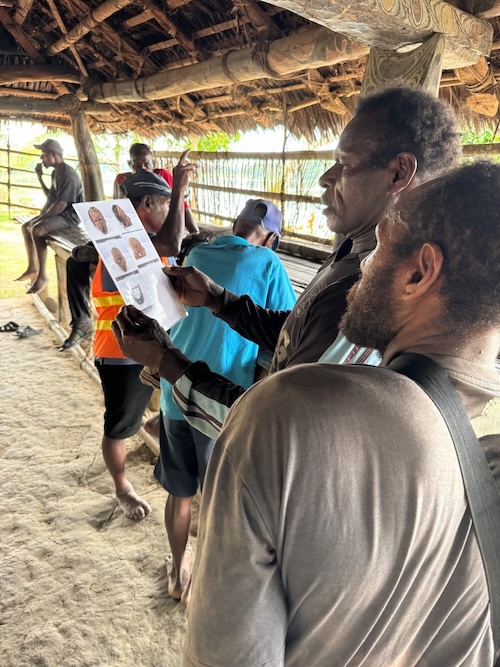

Paul Voogt, the museum’s curator, traveled to Papua New Guinea to discuss the potential return of the skulls with modern-day Iatmul communities. Despite acknowledging the historical and cultural significance of the objects, the communities declined the offer to have them returned.

Insect display Mussiemuseum. 23 June 2017, photo Kleon3, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

The Papuan communities expressed two key reasons for their refusal. Firstly, there is a deep-seated fear of curses associated with the skulls. Without clarity on whether the skulls belonged to revered ancestors or fallen enemies, villagers are wary of reintroducing objects that could bring harm or misfortune. As Voogt explained, they said that, “If we bring them into our village, this could cause harm to the village, a curse.”

Secondly, the skulls have lost their spiritual significance for the Iatmul people. The tradition of creating and venerating such objects has not been practiced for generations.

According to the Missiemuseum’s description of the repatriation project, “The opinion of the people in the villages was unanimous: they don’t want them back.” Modern villagers see the skulls as relics of a long-forgotten past, with no practical use or relevance in contemporary life. “They have lost their power for us and they are just objects. We have no use for them,” Voogt recounted hearing during his visit.

The Ethical Complexity of Restitution

Papuan skull collection displayed in the Missiemuseum. Photo courtesy Mussienmuseum, 2024.

The case of the ritual skulls underscores the complexity of colonial-era artifact restitution. While some advocates in Europe call for the unconditional return of such objects, Voogt emphasized the importance of consulting the communities from which they originate. In this instance, the Papuan communities not only declined the return but also expressed no objection to the skulls being exhibited in the Netherlands. Some villagers even took pride in seeing their heritage preserved and displayed abroad.

Voogt’s research into the origin of the skulls—whether they were ancestral remains or trophies from battle—will continue, but the objects will remain on display in the Netherlands regardless of the findings. The curator believes this situation demonstrates that restitution is not always a straightforward process. “What it shows, I think, is that the most important thing is to ask people themselves what they think about it. Instead of just drawing conclusions made in Europe,” he noted.

The refusal of the Iatmul communities to accept the return of these ritual skulls illustrates the nuanced realities of artifact restitution. While European institutions grapple with their colonial past, the voices of the communities from which these objects originate must remain central to the discussion. Restitution is not always desired and cultural heritage, when severed from its original context, can take on entirely new meanings and values over time.

The Missiemuseum Steyl is currently considering working with Germany, which is helping the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery (NMAG) in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea to build a new warehouse for its collections and to teach museum conservation practices to its staff. The Missiemuseum is also expanding its online presence in order to inform people in Papua New Guinea and around the world about its collections – and its openness to future restitutions.

Other Missionary Collections

The same issues of religions’ impacts, coexistence and conflict are being discussed in museums holding ethnographic objects around the world. The Ethnological Museum Anima Mundi at the Vatican contains 88,000 objects and is undoubtedly the most famous of all the mission-based ethnographic museum collections. Wantok Place in Adelaide, Australia, which holds 1500 Papua New Guinea artifacts, is a small museum owned by the Lutheran Church of Australia, with 1500 objects collected starting in the 1880s by the first Lutheran missionary to Papua, Johann Flierl. Collecting by missionaries has also formed the basis of public museum collections around the world, such as the Namibian collections at the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin, which recently repatriated 23 objects. Other object-based mission museum collections include the items assembled by the missionary Carl Spiess for the Übersee-Museum Bremen, the objects collected by the Bael Mission from Cameroon now at the Museum der Kulturen Basel (MKB) in Switzerland, those of the London Missionary Society Museum, and many others.

Missiemuseum Steyl

Father Arnold Janssen, founder of various RC missionary congregations. Collection of Missiemuseum in Tegelen-Steyl, Limburg, the Netherlands, 18 December 2015, photo Kleon3, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

The Missiemuseum Steyl was established in 1931, at the home of the mission of the Society of the Divine Word (SVD). The mission was founded in Steyl in the Netherlands by Saint Arnold Janssen in 1875 to perform missionary activity, focusing on preaching the Gospel in foreign lands. The Society of the Divine Word has grown to become the largest international missionary congregation in the Catholic Church.

The museum accepts requests for study or loans through its website, https://www.missiemuseum.nl/en

Starting January 17 and running through 29 June, a museum exhibition is featuring three films made by priest cinematographer Father Simon Buis on the island of Flores in the 1920s and 1930s. The films are fantasies modeled on Hollywood-style tropes of forbidden love, forced marriage, neighborhood wars and also, Christian love.

Poster for exhibition Hollywood Op Flores, De films van Pater Simon Buis SVD, Missiemuseum.

Missiemuseum Steyl

St. Michaelstraat 7

5935 BL Steyl

The Netherlands

Papuan men examining images of the objects in the Missiemuseum. Photo by Bruno Waterfield for the Missenmuseum.

Papuan men examining images of the objects in the Missiemuseum. Photo by Bruno Waterfield for the Missenmuseum.