May 27, 2022 Fire Map, Calf Canyon/Hermit’s Peak fire.

The Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon fire that has now devastated over 315,000 acres of northern New Mexico began as a ‘prescribed burn’ on federal lands on April 6. The fire started near the base of the Pecos Wilderness near Las Vegas, New Mexico – a quiet former frontier town with a ‘main street’ fronted with banks, cafes, and antique stores, not lined with casinos, like the other Las Vegas in Nevada.

The fire is now 17 miles wide and 45 miles long. Over the last two months, it has roared through tinder-dry forests northward to the edges of Taos County, threatening Taos Pueblo lands and the Angel Fire Ski Resort to the north. Westward, it has burned frighteningly close to the town of Pecos but has been held back from Santa Fe itself through the extraordinary efforts of some 2000 firefighters.

This is a place of isolated rancheros and tiny traditional communities tucked into the mountains, where villagers can often trace their ancestors back to the conquistadores or before and where small communities retain traditional rural lifeways admixed with the modern. With the fire and consequent loss of homesteads, many cultural traditions may end.

Hermit’s Peak, where the fire began, got its name from a real hermit, Giovanni Maria de Agostini. Agostini was born in Italy and though initially a member of the Maronite Church, was attracted to the life of a solitary wanderer and hermit from an early age. He went first to Brazil where he developed such a large following of believers in his ability to perform miraculous cures that the government considered him dangerous and arrested him.

Giovanni Maria de Agostini, Palace of the Governors Photo Archives Collection, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

He went to Mexico in 1861, where his mysticism and piety again brought him followers, but records show that he was also held in an insane asylum. From Mexico, he travelled to Cuba, was again expelled, then to New York, from which he walked to Montreal in Canada where his disheveled appearance made him coldly received, then returned to the U.S. and joined a wagon train to Kansas, walking all the way.

Las Vegas was a terminus on the old Santa Fe Trail and Agostini found its wilderness the perfect place to establish himself. He lived for three years in a cave high up on a mountain peak, walking down to Mass in the town, and living by foraging and on donations from the devout. A tradition that sprang up among the locals of walking to his cave to visit him and to pray evolved into an annual pilgrimage to obtain his blessing and cures for ailments. After Agostini’s departure, the tradition of pilgrimage to the hermit’s cave, following the Stations of the Cross continued. Eventually it diminished, but even in the 2000s the Abeyta family walked there every year, praying and erecting crosses enroute.

Agostino himself left Hermit’s Peak after three years to stay in another isolated spot in southern New Mexico. In 1869, he was attacked and killed by robbers as he attempted to carry a gift of gold from a priest to be delivered to needy Indians in Mexico.

There is no word yet on whether the now revered Hermit’s Peak cave of Agostini was completely destroyed in the fire; but the region surrounding it has burned.

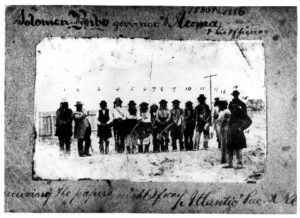

Solomon Bibo (#15) (July 15, 1853 – May 4, 1934), governor of the Acoma Pueblo. Taken for his 1885-86 term as governor of the Pueblo, presumably in 1885.The words at the top read: “Solomon Bibo governor of Acoma & his officers 1885 – 1886″; According to notes on the photo:”From left to right: 1) Jose Miguel Chino 2) Pedro Sanchez (Indian agent) 3) Hashiti* Martin de Valle 4) Jose Berendo (principal) 5) Santiago Orilla 6) Santiago Conepo Linazeteah 7) Lorenzo Pancho 8) Lorenzo Lina 9) Larenzo Schaurva Kruz 10) Toribio Mateai 11) Jose Ant Aujune (Bibo) 12) Napoleon Pancho (Bibo) 13) Andres Ortiz (Interpreter) 14) Mr. Read, Secretary of Indian Agent 15) Solomon Bibo, Governor of Acoma,” Source The Leona G. and David A. Bloom Southwest Jewish Archives, public domain.

Some travelers who were drawn to New Mexico for less than spiritual reasons have found themselves playing unexpected but life-changing roles in the desert West. One New Mexico story leads to another, so here is the tale of another stranger who arrived in the United States in 1869, the year Agostino died. This man, Solomon Bibo, played an essential part in the history of the Native American community at the Acoma Pueblo, today one of most respected and influential Native American sovereign nations among New Mexico’s twenty-three federally recognized tribes.

Solomon Bibo came to the United States from Prussia to join his two older brothers who had settled in Santa Fe. The Bibos were just one of several Jewish families who came to the Southwest as small traders and ended up as prominent citizens.[i]

In the 1860s and 1870s, the Bibo brothers opened dry-goods stores selling basic foodstuffs, seed, and farming tools in communities across the region, trading with the resident Hispanic and Native American communities. One store, located at Cebolleta, was adjacent to Navajo; another was established outside of Laguna Pueblo.

Solomon Bibo went on a trading trip to Acoma, where he spent a week and established good relations, returning to Santa Fe with corn and a load of the Acoma’s skilled pottery creations. Returning to Acoma again, he was invited to the primary settlement, atop a 300 foot high mesa. The then Acoma leader, Governor Martin Valle, welcomed Bibo and helped him to set up a small trading post next to the Catholic church on the mesa. Despite hostility from the local priest, Bibo persevered, learned to speak the local language fluently and courted Governor Valle’s granddaughter Juana.

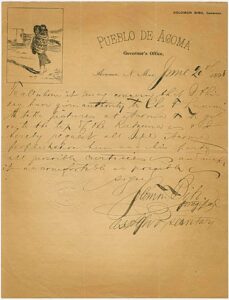

Solomon Bibo, 1853-1934, author, Letter, Date 1898. Letter Solomon Bibo of the Governor’s Office of Pueblo de Acoma in New Mexico wrote on June twentieth giving authority to Chas F. Lummis to take pictures at Acoma.

There is a famous story in New Mexico of the priest’s journey by mule all the way to Santa Fe to complain to Bishop Lamy[ii] about a Jew becoming influential in Acoma. The Bishop is said to have put his arm around the priest, led him to the doors of the cathedral, and pointed to the sill. On it was carved the silent Hebrew name of God. Pointing out that Santa Fe’s Jewish Speigleberg family (relatives of the Bibos) had actually donated much of the construction cost for the new cathedral, the bishop sent the priest back to Acoma.

In 1884, Bibo was able to assist the Acoma by supporting their claims to their ancestral lands against Anglo, Mexican American and Laguna Indian interests. While he certainly also profited himself in his financial dealings with the Pueblo, he was sufficiently respected to have strong Acoma support for his appointment as Governor, the Acoma equivalent of Chief. The Acoma elected him their Governor for four separate terms.

Some of Bibo’s actions are considered negative today. He was a strong supporter of education, both locally at the Pueblo and in sending Indian students to faraway boarding schools. These schools are recognized today as oppressive and as having aggressively and inhumanely forced children to assimilate and lose their languages and culture. By contrast, during Bibo’s governorship of the Acoma, he was regarded by White and Hispanic settlers as extremely pro-Indian and anti-establishment.

The old church at Acoma Pueblo, date 1902. Public domain.

Solomon Bibo married Juana, probably in the Catholic church, and Bibo was accepted into the tribe. She is said to have converted to Judaism, and they raised two sons as both Jewish and Acoma – one was known as Carl – but two young men are identified in a photograph taken at Acoma in 1885 as Jose Ant Aujune (Bibo) and Napoleon Pancho (Bibo). Eventually, Solomon and Juana Bibo left Acoma and moved to San Francisco with their children. It is said that one of their sons went back to Acoma for a traditional Pueblo manhood ceremony after his Bar Mitzvah, but it is not known whether he stayed.

[i] Many Jewish traders served as officials in the 19th c. New Mexico territory and during early statehood. New Mexico became a state in 1912. In 1931, native son Arthur Seligman became mayor of Santa Fe and then Governor of the State of New Mexico.

[ii] Bishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy is well known for his work to reform the New Mexico church. His life is fictionalized in Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop.

Pueblo Governor Solomon Bibo with members of Acoma Pueblo.

Pueblo Governor Solomon Bibo with members of Acoma Pueblo.