A prosecutor from the New York County District Attorney’s office walked into the booth of English art dealer Rupert Wace at the gala opening of The European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF) at New York’s Park Avenue Armory on October 27. He was holding a search warrant and accompanied by uniformed police officers, who seized a limestone bas relief from Persepolis in Iran. The relief was worth $1.2 million. Wace had purchased it from an insurance company, which had acquired it from the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

The New York District Attorney’s office, under the aggressive direction of DA Cyrus Vance and dedicated anti-art trade crusader Assistant DA Matthew Bogdanos, has made two cultural property seizures in recent weeks. Neither object was recently looted; together, they had been in museums or private collections for over 115 years.

There was no evidence of wrongdoing by the collectors or dealers involved. Wace had purchased the bas relief after it was given up by the Canadian museum. The other seized object, a fragment of mosaic from Italy, was purchased in the 1960s by a journalist and his wife, an antique dealer, from an aristocratic family in Italy. According to the couple, the deal was brokered by an Italian police official “famed for his success in recovering art work looted by the Nazis.”

These cases raise serious questions, impacting both private and museum collections in the US. When an artwork is well-known to scholars, published or exhibited, how long is too long for a country to make a claim? Will museums and collectors in the US that are second, third, or fourth generation owners be held to vague, ambiguous, and unenforced laws in foreign nations, when those nations have failed to make any claim for decades? At what point do US judges or law enforcement consider whether the evidence, or the terms of the foreign laws, actually provides a reasonable basis for a claim that an object is ‘stolen’?

The Iranian Law

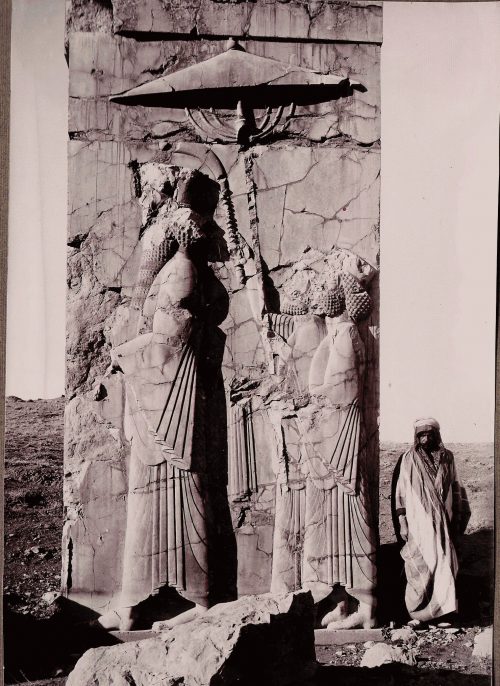

Stone Panel, Credit Rupert Wace

There is serious doubt whether the Persepolis bas relief qualifies as stolen property under Iranian law. The seizure was ostensibly based on a 1930 Iranian law, the National Heritage Protection Act dated November 3, 1930, and the Regulation Implementing the Law dated Nov. 3, 1930 relating to the Conservation of Antiquities in Iran (3 Nov 1930) (“1930 Regulation”).

Yet this National Heritage Protection Act, along with its 1930 Regulation, does not appear to be the type of national ownership law that could enable a claim to be enforced under US law. Simply having Iranian art outside of Iran does not make it ‘stolen.’ The Iranian National Heritage Protection Act does state that all artifacts shall be considered national heritage, and shall be ‘protected,’ but does not say that all antiquities are state-owned. In fact, the 1930 Regulations allow continuing private ownership and even sale in Iran of an “immovable antiquity with protected status” (Chapter I. Article 7). The 1930 Regulation also allow owners of movable antiquities to sell them if notice is given 10 days before to the government (Chapter II. Article 16). Indeed, the 1930 Regulation allows commercial trade even in “immovable National Monuments” when they are approved for sale by the Minister of Education (Chapter IV. Article 41.)

Legal Commercial Looting in Iran up to WW2

If claims based upon misreading this foreign law go forward, then New York’s famous archaeologically excavated collections from the Metropolitan Museum’s Nishapur expeditions – and many important collections in other museums – are vulnerable.

The Nishapur excavation’s history clearly shows how foreign archaeologists removed items from Iran legally after 1930, by buying a ‘concession.’ They also show that legal, purely commercial exploitation of archaeological sites was prevalent until at least 1947, when the Met’s concession was terminated. The operation of Iranian law, as it affected this scholarly expedition, is vividly described on pages xxiv and xxv of the Introduction to Charles K. Wilkinson, Nishapur, Pottery of the Islamic Period, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973. The book also describes how the American archaeologists deliberately refrained from buying archaeological material from dealers who sold it openly in the bazaars, acquiring surface finds only directly from peasants at the site, in order not to confuse the record. (It is said in the archaeological community that the expedition lost its concession for Nishapur, not because the Iranian authorities were trying to preserve the site, but because the Met was outbid by commercial diggers.)

For example, from the Introduction:

“Here it may be said that it is not possible to give the entire picture of the pottery of Nishapur from the Sasanian period to modern times…The subsequent ravaging of the sites for commercial purposes has made any future attempt much more difficult…Some of this digging was technically legitimate, an unfortunate clause in the antiquities law of 1930 permitting commercial excavation so long as part of the finds are turned over to the Muze Iran Bastan. The intention was to give the Iranian Antiquities Service, at no cost to itself, knowledge of the ancient sites of Iran, but it is deplorable nonetheless that a site proved of the first importance should be opened to ruthless exploitation. Nishapur deserved a better fate than death by looting.”

This dramatic picture of state-sanctioned looting, and the clauses of the 1930 law cited above, give the lie to any claims by the District Attorney that the seizure is justified under the 1930 Iranian law without evidence to establish that the ancient stone relief was unlawfully excavated, or that its export was forbidden by the Iranian authorities. The statement by Ebrahim Shaqaqi to the Tehran Times seems to confirm that as yet, the claim is based upon speculation, not evidence: “Legal follow-ups are underway to first prove that the relic belongs to Iran and finally repatriate it.”

History of the Seized Bas Relief

The seized relief is said to be from a site excavated by the Oriental Institute of Chicago in 1933. (It is known that the members of the Oriental Institute expedition actually received permission to take some pieces from its excavation out of the country. It is not known if the bas relief was removed during the excavation, or was part of a permitted commercial antiquities business.) However it came to the Americas, the seized relief had been donated to the Montreal museum by collector and department-store heir Frederick Cleveland Morgan in the 1950s. It was placed on exhibit for more than 60 years, but was stolen from the museum in 2011 and then located several years later by the museum’s insurance company. The museum decided to keep the insurance payment in exchange for title to the object, and the insurance company sold it to Wace.

Mr. Wace told the NY Times via email, “This work of art has been well known to scholars and has a history that spans almost 70 years…We are simply flabbergasted at what has occurred.” Scholars commenting in the NY Times article mentioned that reliefs from Persepolis are found in museums around the world, as they were collected and removed by the dozen in the 19th and early 20th century, when Iranian law did not prevent it. What they did not mention is that Iranian law condoned commercial looting for decades afterward.

Another Day, Another Seizure, Another Foreign Law

A different set of facts, and different foreign laws were at work in another seizure a few weeks earlier. Four years after starting to work with Italian authorities (who do not seem to have been very excited about the matter) the District Attorney’s office seized a piece of mosaic flooring with an abstract design from the New York home of European antiques dealer, Helen Fioratti. Ms. Fioratti said she and her husband, journalist Nereo Fioratti, had purchased the piece in the 1960s. The marble flooring had once been part of an enormous ship used as a floating palace by the Emperor Caligula at Lake Nemi. Two of Caligula’s ships were dredged from the lake by the Mussolini government in 1932, and a museum was built nearby to house artifacts from them. Partisans used the museum as a bomb shelter during WWII, and at its close, set fire to the building. The artifacts were lost in the fire or disappeared.

The Fiorattis purchased the mosaic, according to Ms. Fioratti, through an Italian police official more than twenty years after the museum was burned. They knew nothing of the connection to the museum and believed their ownership to be completely legal. They displayed the fragment of flooring as part of a coffee table in their home. “It was an innocent purchase,” Ms. Fioratti told New York Times writer James C. McKinley, Jr. “It was our favorite thing and we had it for 45 years.” She told the Times that she would not contest the seizure because of the expense and time it would take.

Museums Are Vulnerable Too

If the seized bas relief, which which had 70 years of provenance, can be claimed to be ‘stolen,’ then so can tens of thousands of other items in American museums. For museums in particular, antiquities claims based on old and previously unenforced foreign laws raise urgent questions; their inventories are full of objects for which the original records of export no longer exist. Foreign permits were not required for importation or sale and such records were not relevant to establishing good title or required for donation. The ethical goalposts for museum acquisitions have been moved over the years, and what was common practice in the past may be unacceptable today, but imposing today’s standards on the past doesn’t help resolve issues regarding ownership of collected in the past.

Luckily for museums, prosecutors seem more eager to target art dealers than august institutions. After all, mere possession of a ‘stolen’ object is a continuing violation of the National Stolen Property Act. If ‘stolen property’ laws were as strictly enforced against museums as they are against the art trade, then museums would be stripped, trustees would be unwilling to serve, and the public deprived of access to art and history. There might then be real impetus to reform laws that harm the public interest. That is something that aggressive campaigners against the art trade want to avoid. But museums aside, if far-fetched claims like those raised against Wace by the NY District Attorney are not challenged, then New York will surely lose its place as a center for the international antique trade. How can businesses operate if 70 years of provenance is not good enough?

US Prosecutions Are Based on Foreign Laws

It is a principle of US law that no purchaser of a “stolen” object, whether a car or an ancient sculpture, can gain good title. It makes no difference how many hands it has passed through, or whether the purchase was thought to be legitimate. The object remains “stolen property.”

When police seize an ancient artwork as “stolen property,” it is often by using a national ownership law that states that all antiquities (often, all objects over 100 years old) are the property of the foreign government of the source country. Even if, at the time of the removal, the foreign law existed only on paper, and was not locally enforced, a long court case ensues. A year or more may pass before a judge can rule on whether that foreign law is enforceable in the US as a national ownership law, or if the law simply prohibits export, in which case it is not enforceable, or, if a valid (on paper) foreign law was not enforced in the foreign country at the time.

Few art dealers or collectors can afford the costs that such a lengthy legal process entails, and few objects are valuable enough to be worth fighting for. Museums are even less likely to fight a seizure; they cannot afford to suffer negative publicity or be called looters in the press. The result? Both museums and collectors give up objects without a fight and the prosecutor declares another ‘moral’ victory. To some, it might seem more like extortion by the source country, or at the least, a cover-up of the source country’s failure to follow its own laws many years ago. (Others might find pursuing a case on behalf of Iran at a time when that country holds US citizens in prison on trumped up charges, an uncomfortable task.)

Some common sense arguments can be made against all these ‘sleeper’ claims – the kind of claims that arise only when an ancient artifact is known to be particularly valuable, as this Iranian bas relief was.

How Long is Too Long?

When foreign governments sleep on their rights and fail to make claims for decades, then many believe it is unjust to place the burden on good faith buyers. When a case is 70 years old and weak to begin with, the evidence of how export occurred is no longer available, and the witnesses are long-dead, then society ought to move on.

The legal principles of repose and laches both rest on the idea that a long delay on the part of a claimant makes it unreasonably difficult for another party to defend itself. (Imagine waiting 40-50 years to make a claim that something disappeared from your home. And imagine that the object had been publicly displayed in a nearby museum the whole time.)

But the NY District Attorney’s office seems more focused on making headlines than ensuring that cases are justified before they act.

Persepolis, early 20th century, private collection

Persepolis, early 20th century, private collection