Cycladic idol seized by NY District Attorney and sent to Greece.

In December 2023, a highly publicized return of 30 antiquities to the government of Greece included an antiquity with over seventy-years history of lawful ownership, exhibition, and publication in the United States – and decades of before that in Europe. Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg’s splashy announcement of the return of ‘looted’ and ‘stolen’ objects at a recent repatriation ceremony with Greek officials didn’t begin to tell the whole story.

Nineteen of the returned objects were ‘voluntarily surrendered’ by New York dealer Michael Ward after he was indicted in New York for criminal facilitation in the Fourth Degree, a misdemeanor. Ward had admitted signing documents he knew to be inaccurate while helping a Bulgarian dealer to create false provenances for objects. Some objects that Ward had purchased or taken on consignment had turned up in the DA’s prosecution of collector and hedge fund billionaire Michael Steinhardt. Ward said he was unaware of the extent of the Bulgarian dealer’s actions until informed by the DA.

One notable object returned to Greece was a Cycladic marble figure that came from another source altogether. The eight-inch-high sculpture seized from the storage space of the former spouse of a longtime private collector didn’t fit the DA’s favorite narrative about returning stolen objects or righting wrongs. Instead, its return to Greece appears to be an example of high-pressure tactics directed by the DA against an innocent owner – in which the DA seized private property where there was no actual evidence of any crime. If there was any evidence of wrongdoing, the DA did not make it public. And in this case, the Cycladic idol had a published, U.S. exhibition history going back to the 1950s and an ownership record and provenance decades older.

Cover, 1955-56 Harvard University Fogg Museum exhibit that included the Cycladic Idol.

The Antiquities Trafficking Unit (ATU) in the New York County District Attorney’s Office is a surprisingly large and well-funded investigative department in which researchers go back decades to locate antiquities imported through New York that are now – 30-70 years later – in the hands of collectors and museums across the United States. Unbeknownst to their current owners, a recent claim by a source country or a find of a photograph in closed police records of past investigations in Italy or Greece is enough to trigger issuance of a warrant from a NY judge.

The 20-plus person team at the ATU is led by Assistant Manhattan DA Matthew Bogdanos. Bogdanos’ investigations are a rich source of public attention for NY County District Attorney Alvin Bragg. A review of press releases under Bragg’s administration shows that from 7-11% press releases issued annually are not about fighting crime today in New City – muggings, murders, and major thefts – but instead about the return of ‘stolen’ antiquities and how the DA is sending them back to Italy, Greece, Yemen, Syria, Libya, Lebanon, Iraq – and even to the Palestinian Authority.

Why Didn’t the DA’s Investigators Make the Cycladic Idol’s History Public?

Odyssey of an Art Collector: Unity in Diversity – Five Thousand Years of Art. Fig. 3.

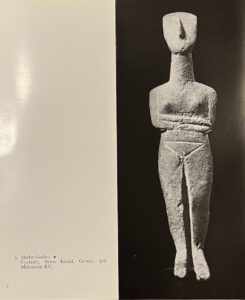

The return of the small Cycladic idol as a “stolen” object to Greece raises many questions. The sculpture, a slight, highly abstracted figure of a woman with folded arms, was returned without any explanation– no evidence was presented of a crime, not even a bad provenance or suspect collection history – and no evidence showed that it was looted or smuggled. Nor was its collection history mentioned by the DA, although for an object just under eight inches high, it appears to have been been well documented since the 1950s and has been featured in several exhibitions in the U.S.

The tiny sculpture was first published seventy years ago in a 1954 catalog of an exhibition entitled Ancient Art in American Private Collections at the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. This is undoubtedly the same object as the one returned to Greece by the ATU. The breaks in the arms, the pubic triangle, the granular surface, the straight incision marking the upper right arm and the proportions of the abdomen are the same. The sculpture’s feet had been minimally restored years ago by a New York restorer who also recognized the sculpture.

The catalog entry included a photograph, a description, and the names of the owners, Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Stafford. (See Ancient Art in American Private Collections, fig. 127B and Addenda, p. 43)

Catalog description of the Cycladic idol with Alphonse Kahn provenance.

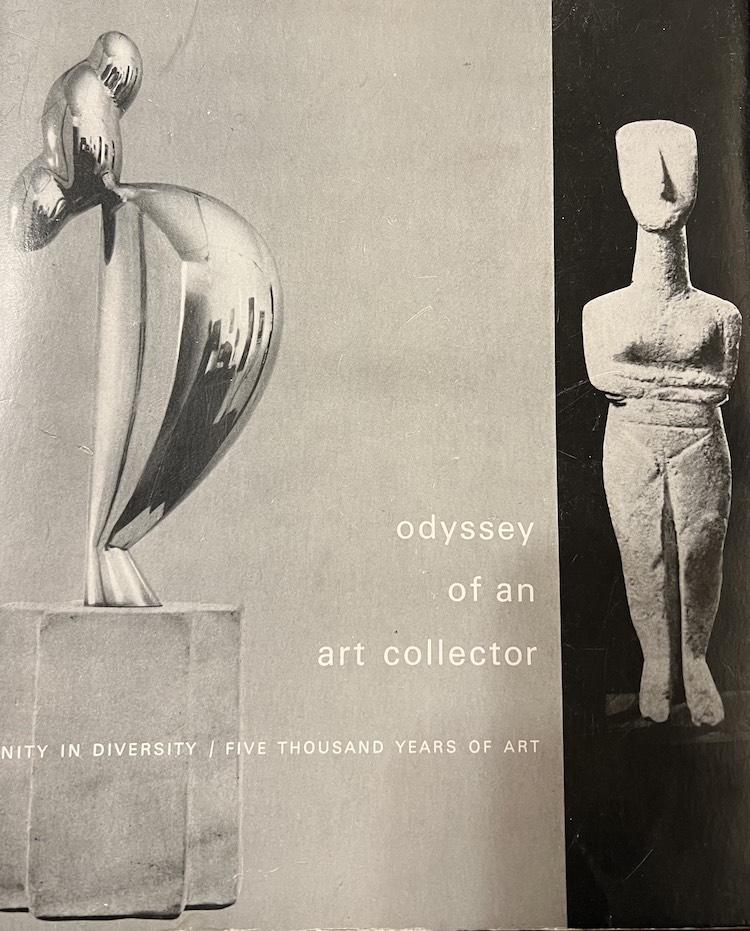

This was not the only publication featuring the same Cycladic idol. It was also published, together with a metal sculpture by Brancusi, on the cover of a 1966-67 exhibition at the Isaac Delgado Museum of Art in New Orleans. This time, the Staffords’ collection was the sole focus – the exhibition was entitled Odyssey of an Art Collector: Unity in Diversity – Five Thousand Years of Art. This catalog also provided a prior provenance for the object, stating that it came from the collection of the famous Paris dealer Alphonse Kahn (or Kann), one of the largest and most eclectic art dealers of the early twentieth century, who died in 1948.

In the 1950s and 60s there were no concerns whatsoever about concealing a foreign provenance to justify falsely ascribing the piece to a prior collection in the Stafford or Fogg catalogs.

The Cycladic idol circulated in the American market for at least seventy years. Information on the history of the idol was available to any researcher through the Internet. Why didn’t the DA’s team of investigators know this? And if they did, why did they keep silent?

There was no evidence that the Cycladic sculpture came from any unlawful source whatsoever. If, as it appears, the object was seized from a storage locker of the former spouse of a U.S. collector who acquired it subsequent to the Staffords and other owners, why was it taken?

The Cycladic sculpture had not only circulated in the U.S. market decades before the 1970 UNESCO Convention, it had been published twice – once on the cover! – in major U.S. exhibitions. What evidence does Bogdanos have to return the property of an American citizen to another country? Did Greece ask him to return it now? If yes, why didn’t they ask before?

NY Prosecutors Deliberately Ignore the History of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Art and Antiquities Trade

Showcase on the first floor of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, probably 1913. Università degli Studi di Milano, Eg. Arch. & Lib., Varille Collection. Plate 23, Piacentini. “When the Museum moved to Midan Ismailya — now Tahrir, in the first years of the Twentieth century, the Sale Room was located in room 56 of the ground floor, accessible from the western entrance…

(pls xvii-xviii). Id. at 116.

The seizure of the Cycladic idol is an excellent example of how Bogdanos and other anti-art trade extremists have promoted a false narrative about the trade in antiquities. Sadly, Bogdanos is joined by academic enablers, who remain unfazed by his outrageous claims about a (non-existent) billion-dollar antiquities market. They surely know better. Antiquities form by far the smallest sector of today’s art market and with rare exceptions, are its lowest valued objects.

Academics and archaeologists, including some who are prominent in condemning the antiquities trade today, are well aware that at the same time that foreign archaeologists were exploring and excavating sites, establishing professional processes and writing the ancient histories of the Mediterranean and the Near East, art dealers, collectors, and museums were invited to visit the same source countries and openly acquired antiquities directly from excavators as well as from local dealers.

Italy, Greece, Egypt, Turkey, Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Lebanon were all open resources for dealers and collectors. The trade in Egypt, whose government licensed antiquities dealers and permitted legal export until 1983, has been documented in detail by Fredrik Hagen and Kim Ryholt in The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930: The H.O. Lange Papers. The book even documents the existence of an antiquities salesroom where visitors could purchase items inside the Cairo Museum. Yet the Egyptian government issued permits for whole “crates of antiquities” and kept no records, rendering proof of legal export unobtainable for tens of thousands of objects today.

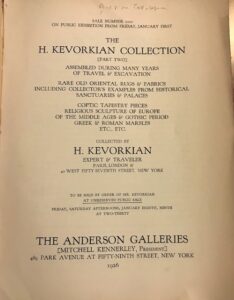

The catalogs for U.S. and European sales by antiquarians C. & E. Canessa (1924) and Hagop Kevorkian (1926) illustrated here, and records of other sales exhibitions show how ancient objects were readily marketed in the U.S. In 1914, Kevorkian invited the NY public to the Galleries of Charles of London on Fifth Avenue for the “Exhibition of the Kevorkian Collection Including Objects Excavated Under His Supervision.” Similar sales were held by other dealers. In 1914, the prominent dealer Joseph Brummer closed his Paris gallery and moved to New York. His East 57th Street gallery sold Medieval and Renaissance European art, and Classical, Ancient Egyptian, African, and pre-Columbian objects as well as holding some of the earliest exhibitions of modern European art in the United States. After Brummer’s death in 1947, part of his private collection went to the Metropolitan Museum; another 2400 lots were sold at auction in 1949. From 1931 until 1948, Brummer had owned the 5,000 year old Guennol Lioness; between 2007 and 2010, it was the most expensive sculpture sold at auction.

Kevorkian Collection sale in New York in 1926 of objects “excavated” under his supervision.

Anyone who knows art history also understands the importance of ancient and ethnographic art in the development of modern and contemporary art. Consider the placement of the seized Cycladic idol next to a dramatic sculpture by Brancusi on the cover of the 1966 Delgado Museum catalog. Nothing could better illustrate the fact that many of the greatest twentieth century art dealers, from Alphonse Kahn to Andre Emmerich, dealt not only in contemporary and modern works but also in ancient artworks. They, like the living painters and sculptors they represented, understood how the formal qualities – and the messages carried by ancient artworks – have informed modern art. Consider also the collector Alfred Barnes’ hanging an antique African mask a few inches from a portrait by Picasso, displaying a Marsden Hartley with an Egyptian Ba-Bird of painted wood, or a red-figured pelike with a still life by Cezanne. To take the position that art is only meaningful within the borders of the present-day countries where it was made thousands of years ago not only denies history, it shows a complete ignorance of how art and art history have worked together for centuries.

New York’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit Defines the Crimes

Page showing Cycladic idol, plate 127B, Ancient Art in American Private Collections, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1955-56.

The New York’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit headed by Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos has racked up quite a record of supposedly looted objects returned to source countries – but like the claim that the Cycladic figure is “stolen,” Bogdanos’ claims are often founded on dubious evidence never put to the test in the courts. Some returns from good-faith buyers of objects several generations away from the hands of ‘suspect’ dealers happen simply because owners fear bad publicity. Other current owners are spooked by the threat of felony prosecution for possession of a ‘stolen’ object under NY’s aggressive pawnbroker law.

Almost all ancient artifacts and artworks in United States collections were duly declared and entered the U.S. legally. Even well into the 21st century – and even today for objects from many countries – all that is legally required to import antiques or antiquities to the U.S. is an honest statement of age and the price paid, the same as for any other goods. Until very recently, with the signing of cultural heritage agreements with some thirty countries, it made no difference to U.S. Customs if a source country forbad the export of antiques – Customs didn’t ask for and didn’t want to see export permits and wouldn’t accept foreign documents except for Certificates of Origin – U.S.-made forms that would enable entry at reduced tariffs for favored nations. Customs wanted declarations written by the importer and in English only.

Assistant DA Matthew Bogdanos (Cen. R), former NY County DA Cyrus Vance (Cen. L) and members of the antiquities trafficking unit with seized objects at a press event celebrating their achievements. Large vessel at center was seized from Fordham University, a gift of former federal attorney William D. Walsh, who broke the Genovese crime family. Credit Office of New York District Attorney.

Even though source countries paid little or no attention to exports of antiquities decades ago, it appears to be enough for Bogdanos and his twenty-plus investigators in the Antiquities Trafficking Unit to justify seizures today if the source country had a law on the books any time in the twentieth or even the nineteenth century. It doesn’t appear to matter whether the DA has evidence of how or when the object left the source country or whether its law was ever enforced. In the case of Mediterranean-sourced objects from Italy, Greece, or Turkey, for example, the DA doesn’t even need proof which country was the true source.

It has to be asked – is there so much money for prosecutors and police and so little crime in NYC that twenty or more NY investigators should do nothing but enforce foreign laws against U.S. citizens and U.S. museums? Especially when these supposed ‘crimes’ occurred 20-40-60 or even 100 years ago?

How much is Bogdanos’ obsession with supposedly looted objects costing the New York District Attorney’s office? It is already abundantly clear that Bogdanos’ values for seized objects are uniformly and preposterously high. Bogdanos’ claims that international criminal networks and ‘terrorists’ are linked to the art trade are likewise unsupported. The most respected analysis of the international antiquities trade, by the RAND Corporation, not only refuted Bogdanos’ claims about terrorist involvement in the antiquities trade but laid the blame for the media’s wildly exaggerated numbers for the international trade directly at Bogdanos’ door. (See, Why is the Manhattan DA’s Office Publishing Data it Knows to Be Untrue?, CPN, December 6, 2023)

Damning the Art Dealers

C & E Canessa NYC sale, 1924, of Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Gothic and Renaissance Sculpture , Enamels, Primitive Paintings, Early Tapestries Orfèvrerie, Italian Majolica and Furniture.

Assistant DA Bogdanos’ strategy is to stigmatize art dealers without giving them an opportunity to defend themselves. He has to some degree a military mind and knows well the power of ‘shock and awe.’ Certainly, there are art dealers with bad records, but Bogdanos has methodically worked to taint as many antiquities dealers as possible by association rather than actual bad actions. Bogdanos named twelve art dealers in the Steinhardt Complaint and stated or implied that the dealers only sold newly excavated ‘fresh’ material. This is absurd.

In an art world in which antiquities dealers are almost all small businessmen, specialists in different fields who frequently sell objects to other dealers before they find a home with a collector, it’s not difficult to find a transaction with missing records from decades before, when, as noted above, provenance was not even considered an issue.

Today, according to Bogdanos, virtually all dealers are criminals because they bought objects third hand or at public auction that were sold by traffickers twenty or thirty years before. The goal is to make artifacts from as many dealers as possible automatically suspect.

Once a dealer is accused of selling a looted object, everything that the dealer has ever sold is deemed looted unless there is proof of legality established through foreign export permits, which were never issued by foreign countries in the first place. Regardless of how the dealers acquired the objects, whether purchased from another dealer or from an auction house, they are considered “stolen.” Yet the original dealers in Italy, Greece, France, and the Near East– whether they were officially licensed, legitimate sellers, or clearly “baddies” with reputations as illegal diggers, were not charged, prosecuted or convicted in their home countries.

Assistant DA Bogdanos claims jurisdiction over every object that was ever imported into the United States through New York, by saying that New York is a legal “nexus.” He sends dubious warrants for seizure for objects in public and private collections not only outside New York County, but outside of New York State. He relies on collectors feeling threatened and museums being fearful of bad publicity. Bogdanos’ warehouse – which the New York Times described as a ‘museum’ – is so full of objects that his office has told people in other cities and states as far out of his jurisdiction as Chicago or Los Angeles to hold on to the seized antiquities because he has no room for them.

Why should the New York District Attorney spend taxpayer dollars to send back artworks to countries that nationalized all art, based upon foreign laws that would be held un-constitutional takings of private property in the U.S.?

When will the people of New York City demand an accounting by its District Attorney that justifies it in prioritizing decades-old claims by countries, many of which are emphatically anti-American, over the actual crimes that New Yorkers must deal with every day?

Additional Reading:

Antiquities Forum, Why is the Manhattan DA’s Office Publishing Data it Knows to be Untrue, CPN, December 6, 2023.

Kate Fitz Gibbon, Egypt Demands Review of TEFAF Artworks; Study Shows Vast Majority of Egyptian Objects Around the World Acquired Through Lawful Trade, CPN, November 27, 2018.

Kate Fitz Gibbon, Vance Caps Career: Steinhardt Gives up $70 Million in Antiquities, CPN, January 19, 2022.

Catalog Cover with Cycladic idol and Brancusi sculpture, Odyssey of an art collector: Unity in diversity - Five thousand years of Art, Isaac Delgado Museum of Art, New Orleans, 1966-67.

Catalog Cover with Cycladic idol and Brancusi sculpture, Odyssey of an art collector: Unity in diversity - Five thousand years of Art, Isaac Delgado Museum of Art, New Orleans, 1966-67.