The U.S. Interior Department has announced proposed changes to the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, known as NAGPRA.[1] The announcement came after a several-years-long consultation with 71 organizations out of the 574 Native American tribes, 129 Native Hawaiian Organizations and 13 Alaska Native Corporations covered by NAGPRA.

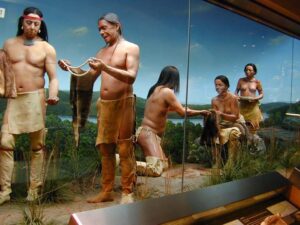

Diorama featuring members of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center, Mashantucket, CT (1997). Author Elliot Schwartz for StudioEIS, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

Many of the proposed changes to NAGPRA represent a reversal rather than a strengthening of Congressional intent in passing NAGPRA. While a number of the proposed revisions 2023 to NAGPRA are practical ones intended to streamline processes and facilitate repatriation of objects, other changes focus on current perceptions of restorative justice. Instead of enabling the NAGPRA Committee to better do its job, they abandon precedent in ways that will encourage ad hoc decision-making by tribes, without public accountability.

There are significant changes in how objects are defined. Objects of unknown heritage would now be classified only according to geographical origin, and claims made when there is no actual evidence of cultural links. Without scientific or historical evidence, classifications as ‘sacred’ or ‘cultural patrimony’ must defer to current beliefs stated by tribes. And – if tribal traditions must be deferred to – what happens when more than one tribe claims an object?

Changes to definitions of what are deemed “federal lands” and Hawaiian lands could also make objects not previously subject to NAGPRA susceptible to claims. These changes could result in many more objects in museum collections being claimed under NAGPRA and in the re-designation of objects from private lands.

Other laws could also be affected by changes to NAGPRA. The STOP Act, which was signed into law on December 21, 2022, restricts export of Native American cultural items. It is already illegal – and has been for decades – to export illegally obtained items. The STOP Act reiterates this but will also require exported objects to first be reviewed by federally recognized tribes, Native Hawaiian Organizations and Alaska Native Corporations and a permit must be obtained for export – the first restriction on the export of art in the history of the United States. There is no value or age threshold, and Native input under the Act will be kept secret.

Side of the National Museum of American Indian in Washington, D.C., Author Aguebor, 10 September 2017. Wikimedia Commons.

When coupled with the proposed new NAGPRA purpose, which mandates that Federal agencies must defer to Native American traditional knowledge, the proposed changes to NAGPRA would exacerbate the constitutional infirmities of the STOP Act. The lack of adequate notice as to what objects are subject to the various provisions of STOP would be further aggravated, rather than improved. Exporters seeking to determine the nature of any object, sacred, cultural patrimony, etc., will not be privy to Native American traditional knowledge and only informed after an alleged violation of STOP. Moreover, these proposed changes will further erode the apparent lack of adequate due process in STOP’s permitting and appeals process. The mandated agency deferral to Native American traditional knowledge appears to create an irrebuttable presumption in favor of a tribe’s characterization of the status of an object.

The impact on the status of Native Hawaiian objects as a result of the proposed changes to NAGPRA is equally concerning in the case of both NAGPRA and the STOP Act. Hawaii has no permanent ‘tribal’ organizations or established community ownership of ‘inalienable’ property. The Native Hawaiian traditional religion was abolished for all practical purposes by King Kamehameha II in 1819. The Kingdom of Hawaii, a feudal society in which property was held by a ruling elite (ali’i), was itself overthrown by American sugar planters in 1893. Today’s more than 125 Native Hawaiian Organizations are effectively self-designated and federally recognized for 5-year periods only. They encompass very broad range of social, spiritual, and business organizations without a consistent ‘traditional knowledge.’

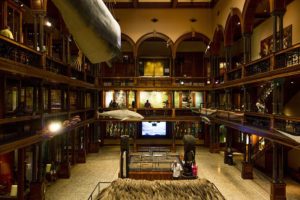

Institute of American Indian Arts Museum, Santa Fe, NM, Author Sarah Stierch, 20 April 2013, CCA 2.0 Generic license.

It is well established under the Spending Clause of the Constitution that the federal government may attach conditions to federal grants. Applying such conditions to private property holders is a different matter and raises a host of constitutional issues: failure to provide a fair process through inadequate notice of what can or cannot be exported, denial of ability to challenge or appeal a decision – resulting in a loss of constitutionally protected private property rights.

At its most fundamental level, since 1990, NAGPRA has protected Native American and Native Hawaiian ownership rights to sacred and culturally significant items, human remains and funerary objects found on federal and tribal lands. Federally funded institutions must inventory and repatriate these items to tribes that claim them.

No one today can fail to acknowledge the mistreatment to which Native American peoples were subjected or the need to remedy many past wrongs. Few, even in the scientific research community, would challenge the need to respectfully return the hundreds of thousands of human remains collected from battlefields and expeditions to their descendant tribes.

NAGPRA covers far more than human remains and objects associated with them, however. The law also provides a mechanism for the repatriation of “cultural items” that are inalienable from tribal communities either as “cultural patrimony” or as “sacred objects” – categories which can also overlap.

A quick summary of changes:

- NAGPRA’s new Purpose states: “…museums and Federal agencies must defer to the customs, traditions, and Native American traditional knowledge of lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations.”(Proposed Rule, Subpart A, § 10.1(a) Federal Register Vol 87, No. 200, p 63237)

- Definitions of a funerary object, sacred object, or object of cultural patrimony may be according to a lineal descendant, Indian Tribe, or Native Hawaiian organization and based on “Native American traditional knowledge” instead of scientific or historical evidence.

- ‘Affiliation’ for repatriation can simply be a geographical connection.

- ‘Federal lands’ can include lands leased by the U.S. government.

- Hawaiian lands are redefined based upon a traditional division into ahupua’a, somewhat triangular divisions originally pertaining belonging to pre-colonial Hawaiian community lands extending from the tops of mountains to the sea and beyond it.

- The Department proposes to add a new term, ‘‘custody,’’ that would indicate an obligation for human remains or cultural items that is less than ‘‘possession or control.’’

- The term “culturally unidentifiable” is removed entirely and “geographic origin” is “integrated” into the repatriation process to replace an unknown identity with a known concept.

Application to all institutions receiving Federal funds

Cherokee Hills Byway – Trail of Tears Exhibit at the Cherokee National Museum, Oklahoma. The sculptures create an environment where the visitor walks alongside the Cherokees on their route from their homelands to the Indian Territory.

NAGPRA originally was applied almost entirely to museums and federal institutions. However, a 2018 case involved a public library in Medford Massachusetts, which received a donation of a collection of Northwest Coast artifacts in 1880, 110 years prior to passage of NAGPRA. The library wished to auction the artifacts to provide funding for to build a new library. Despite there being no evidence whatsoever that the items had been acquired illegally (indeed, the original collector apparently had a good reputation for purchasing items fairly from Native sources), a firestorm of protest resulted, based upon “moral” and “ethical” grounds rather than the actual law.[2]

The proposed 2023 definition of federal funding[3] broadens the type of collections and institutions subject to NAGPRA. According to an example in the proposed regulations, an educational institution would be deemed subject to NAGPRA for receiving federal funds, for example, through a Pell Grant to a needy student subsidizing their tuition. This interpretation could significantly broaden the number and type of institutions required to inventory and repatriate objects and acceptance of federal funds in one or another institutional sector could require university museums, galleries, and study collections not previously subject to NAGPRA to repatriate them – solely on a claim based on ‘traditional knowledge.’

Changes to the “duty of care” expected of museums and institutions could also impose significant restrictions on the handling of objects based upon ‘traditional practices’ defined solely by what a tribe avers is traditional today.

F. Bartoli, Ki-On-Twog-Ky (also known as Cornplanter, 1796, New York Historical Society Museum and Library, New York, USA.

The proposed regulations may lead to concerns about conservation and preservation of museum holdings:

“(d) Duty of care. Prior to disposition or repatriation, these regulations require a museum or Federal agency to care for, safeguard, and preserve all human remains or cultural items in its custody or in its possession or control. Upon request of a lineal descendant, Indian Tribe, or Native Hawaiian organization, a museum or Federal agency must, to the maximum extent possible: (1) Consult, collaborate, and obtain consent on the appropriate treatment, care, or handling of human remains or cultural items; (2) Incorporate and accommodate customs, traditions, and Native American traditional knowledge in practices or treatments of human remains or cultural items; and (3) Limit access to and research on human remains or cultural items.” (Proposed Rule §10.1 (d) p 63237)

Deference to currently held ‘traditional knowledge’ may lead to unexpected results. In the following example, a perspective held by a tribe today superseded the tribal perspective of the Native American artists who actually made the work.

As described by historian Ron McCoy:

“A 2010 [NAGPRA] notice of intent to repatriate seemed to run directly counter to the law’s intent, as articulated by the Senate Committee. The notice announced plans to transfer 184 “medicine faces” – False Face masks – from the Rochester (New York) Museum & Science Center to the Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians of New York. Claimants characterized these pieces were both “sacred objects” and “objects of cultural patrimony.” This, despite the fact Senecas carved the pieces specifically for public exhibition between 1935-1941 while working with the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration.” [4]

Jesse Cornplanter, descendant of Seneca chief Cornplanter, making a ceremonial mask, Tonawanda Community House, Tonawanda, New York, 1940 National Archives Identifier 519161

Another example of the potential for abuse took place in 2000 with the delivery of 200 objects, including some of the most important Hawaiian carvings known, from the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum to the Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei, a recognized Hawaiian Organization. The group hid the objects in a cave in a remote location on Hawaii Island and refused to divulge their location even after a court order’. A number of scholars disputed that the objects had a sacred character or had ever been ‘buried’ with human remains. Other Hawaiian Organizations disputed the Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei right to claim ownership of the items in the first place.[5] (See NAGPRA in Hawaii: Museum and Native Hawaiian Conflicts).

Tribal claims and traditional knowledge

Arguably, the most significant changes proposed to NAGPRA regulations for 2023 are express statements of purpose and intent that defer completely to tribal definitions of “sacred” and “cultural patrimony” based upon “traditional knowledge.” According to the announcement of the proposed changes to NAGPRA by the Department of the Interior, this change is specifically intended to strengthen “the authority and role of Tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations in the repatriation process.”[6]

Despite the repeated grant of authority to “Native American traditional knowledge”, the proposed changes avoid defining what this means. They end up stating that the term may include “traditional ecological knowledge” or “indigenous knowledge” or “traditional cultural knowledge.” “Native American traditional knowledge” is “inclusive of all these terms and may provide information needed to identify affiliation (either cultural or geographical), funerary objects, lineal descendants, objects of cultural patrimony, and sacred objects.” (C. Section 10.2 Definitions for This Part, 17, p 63213.)

Statue of Mohegan Medicine Woman Dr. Gladys Iola Tantaqudgeon on display at the Mohegan Tribal museum in Uncasville, CT on Nov. 19, 2013. Dr. Tantaqudgeon was born in 1899 and educated in tribal spirituality and herbalism by her grandmothers then studied anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. USDA photo by Bob Nichols, public domain.

The NAGPRA Proposed Rule states explicitly that “…museums and Federal agencies must defer to the customs, traditions, and Native American traditional knowledge of lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations.” (emphasis added) (A §10.1(a) p 63237)

In NAGPRA’s new definitions section, “’Native American traditional knowledge’ means knowledge, philosophies, beliefs, traditions, skills, and practices that are developed, embedded, and often safeguarded by Native Americans… Native American traditional knowledge may be, but is not required to be, developed, sustained, and passed through time, often forming part of a cultural or spiritual identity.”(§10.2 Definitions for this part, p 63239)

In the DOI announcement, Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland stated that NAGPRA “helps us heal from some of the more painful times in our past by empowering Tribes to protect what is sacred to them. These changes to the Department’s NAGPRA regulations are long overdue and will strengthen our ability to enforce the law and help Tribes in the return of ancestors and sacred cultural objects.”[7]

A number of the proposed changes explicitly defer to this ‘traditional tribal knowledge,’ giving this equal or greater weight than scientific and historical data in establishing ‘affinity’ between objects and claiming tribes. The means of identifying an object as a funerary object, sacred object, or object of cultural patrimony subject to repatriation may also be defined according to a lineal descendant, Indian Tribe, or Native Hawaiian organization and based on “Native American traditional knowledge” instead of scientific or historical evidence.

Cultural Affiliation

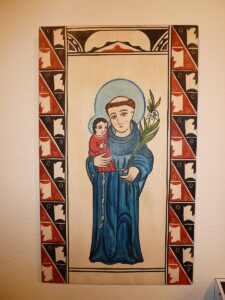

Wallpainting of St. Anthony of Padua, Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, Albuquerque, NM. Author Jim McIntosh, 30 October 2010. CCA 2.0 Generic license.

Under the proposed changes, “one or more of the following equally relevant types of information may be used to identify cultural affiliation: (i) Anthropological; (ii) Archaeological; (iii) Biological; (iv) Folkloric; (v) Geographical; (vi) Historical; (vii) Kinship; (viii) Linguistic; (ix) Oral Traditional; or (x) Other relevant information or expert opinion, including Native American traditional knowledge which alone may be sufficient.

A “shared group identity” is still required to establish cultural affiliation, however, the proposed text also states that, “As two or more earlier groups may be connected to human remains or cultural items, a relationship may be reasonably traced to two or more Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian organizations that do not themselves have a shared group identity.” (§10.3(a)(3), p 63241)

Also, “Cultural affiliation is established by a simple preponderance of the evidence given the information available, including the results of consultation.” (§10.3(a)(1), p 63240) Simple preponderance of the evidence means that something is more likely that not to be true, for example, 51% likely.

Geographical Affiliation

Past NAGPRA regulations relied primarily, though not exclusively, upon historical or scientifical cultural linkages between ancient objects and current tribal entities. As part of the regulatory changes, ‘affiliation’ for repatriation may now be based simply on a geographical connection, for example, in situations where a current federally recognized tribes lives in general proximity to a region inhabited by ancient Native American peoples.

Under the new rules, “Geographical affiliation is identified by reasonably tracing a relationship between an Indian Tribe or Native Hawaiian organization and a geographic area connected to the human remains or cultural items.” (§10.3(b), p 63241) A claim may be substantiated for an ancient object by a current Native American tribe by “a relationship between the geographic area and the Indian Tribe or Native Hawaiian organization, based on the identification of the geographic area as: (A) The Tribal lands of the Indian Tribe or Native Hawaiian organization, (B) The adjudicated aboriginal land of the Indian Tribe, or (C) The acknowledged aboriginal land of the Indian Tribe. (§10.3(b)(2)(iii), p 63241) Also, “Information used for geographical affiliation may provide information sufficient to identify cultural affiliation under paragraph (a) of this section but must not be used to limit geographical affiliation.” (§10.3(b)(3), p 63241)

Inventory, repatriation and ‘geographical affiliation’

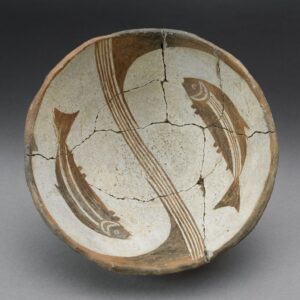

Mimbres bowl, American Southwest photo by Brian Zehowski, 2008, Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, MN.

The new rules maintain the basics of the current method of repatriation but replace the category of “culturally unidentifiable” items with “geographically affiliated” items based upon the findspot – when there is no cultural affiliation. The term ‘geographical affiliation’ simply means that an object is found ‘near’ to lands of an existing tribe. In the Southwest, where 30 or more tribes whose cumulative lands can cover much of a state (such as New Mexico) will all receive a NAGPRA Notice to make a claim, it is already the case that just a few tribes from a much more limited region will consistently make claims while others consistently do not. The result could be that a small number of quite distant tribes will make successful claims, setting precedents for certain tribes to control access to ancient artifacts from a broad geographical area.

This rule change may have begun as a housekeeping measure to facilitate the return of unknown human remains for reburial and making that process easier and more flexible. On the other hand, the return of objects to an unrelated cultural community based upon geography alone constitutes an unjustified removal of objects from an ancient period to the control of an unrelated present day community. While it makes sense to facilitate claims for human remains by nearby tribes to be able to honor even potential, long-ago ancestors with respectful burial, it is not reasonable to allow claims for objects that do not have a cultural affiliation to be “repatriated” to a tribe for which there is no meaningful community and sacred context, based solely upon a “geographical affiliation.” (§10.3 (a-d), pp 63240-63241)

The proposed changes:

- Require repatriation of associated funerary objects with human remains that are geographically affiliated.

- Require updated inventories, following consultation, within 2 years of the effective date of the rule for culturally unidentifiable objects

- Require a notice within 6 months of updating an inventory and establishes timelines, deadlines, and instructions for completing repatriations upon request

Funerary Objects

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, Albuquerque, NM.

The proposed changes restate the definitions of ‘funerary objects’, both ‘associated funerary objects” and ‘unassociated funerary objects.’

“In response to consultation with Indian Tribes and NHOs, the Department proposes to add to the definition of funerary object (and to all specific definitions of cultural items) that identification of a funerary object is according to a lineal descendant, Indian Tribe, or NHO based on customs, traditions, or Native American traditional knowledge.” (§ 10.2 Funerary object).

The NAGPRA committee commentary preliminary to the proposed regulations state,

“With respect to the Act, Congress acknowledged that no general property interest exists either in human remains or in the funerary objects associated with them in a burial… the proposed revision would require repatriation of associated funerary objects whenever the repatriation of human remains is required. Such an action, based on this guidance from Congress, would not result in a taking of property within the meaning of the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution.” (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act Systematic Process, Federal Register, Vol. 87, No. 200, October 18, 2022, p 63227)

Sacred Objects

“In response to consultation with Indian Tribes and NHOs, the Department proposes to revise that a sacred object is, in the words of the Act, ‘‘needed’’ for a traditional Native American religious practice. Such practice could include the need to ritually inter the object. The Department proposes to add to the definition of sacred object (and to all specific definitions of cultural items) that identification of a sacred object is according to a lineal descendant, Indian Tribe, or NHO based on customs, traditions, or Native American traditional knowledge.”[8]

Cultural Patrimony

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, Pojoaque Pueblo, New Mexico. Author Marelbu, 4 August 2014, CCA 3.0 Unported license.

The Commentary sets forth principles defining how cultural patrimony is held within the tribe on Indian terms:

“The Department proposes to revise the definition of ‘‘object of cultural patrimony’’ to clarify what a Native American group or culture is for purposes of the definition. In response to consultation with Indian Tribes and NHOs and a specific suggestion from an Indian Tribe, the Department also proposes to add a sentence to recognize that a caretaker may have been entrusted with responsibility for an object and may have even conferred that responsibility on another caretaker, but the object can still be an object of cultural patrimony. In response to consultation with Indian Tribes and NHOs, the Department proposes to add to the definition (and to all specific definitions of cultural items) that identification of an object of cultural patrimony is according to an Indian Tribe or NHO based on customs, traditions, or Native American traditional knowledge. In the Act, the identification of an object of cultural patrimony is dependent upon consultation with lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and NHOs.”[9]

How Congress Framed NAGPRA to Limit Over-Broad Claims

National Museum of the American Indian (Gustav Heye Center), New York, NY, author Ajay Suresh, 26 Sept 2021, CCA 2.0 Generic License.

Under NAGPRA, tribal traditions have always been held as important in establishing connections to cultural patrimony and were essential to identifying “sacred objects” as connected to spiritual and religious practices by “present day adherents.” However, when NAGPRA was passed, Congress made clear that not all objects could be deemed “sacred” or “cultural patrimony” on that basis. The 1990 Senate report on NAGPRA limits these categories:

“The substitute amendment includes a revised definition of the term “sacred object.” The Committee received comments regarding the ambiguity surrounding the term “sacred,” in particular when that term is used in reference to Native American religious practices.

There has been concern expressed that any object could be imbued with sacredness in the eyes of a Native American, from an ancient pottery shard to an arrowhead. The Committee does not intend this result.

The term sacred object is an object that was devoted to a traditional religious ceremony or ritual when possessed by a Native American and which has religious significance or function in the continued observance or renewal of such ceremony.

The Committee intends that a sacred object must not only have been used in a Native American religious ceremony but that the object must also have religious significance.

The Committee recognizes that an object such as an altar candle may have a secular function and still be employed in a religious ceremony. The substitute amendment requires that the primary purpose of the object is that the object must be used in a Native American religious ceremony in order to fall within the protections afforded by the bill. It has been suggested that some Native American artisans create objects which could be construed as falling within the definition of sacred object and therefore this provision would adversely impact the trade in Native American artwork. The Committee does not intend the definition of sacred object to include objects which were created for purely a secular purpose, including the sale or trade in Indian art.”

“The substitute amendment also includes a revised definition of the term “Native American cultural patrimony.” The Committee received comments from several witnesses regarding the lack of clarity in the original definition of cultural patrimony. These concerns focused primarily on the character of property within traditional Native American societies where property was held by the whole community, not by an individual. It had been suggested that in traditional Native American societies no object could be conveyed by an individual because it was owned by the collective whole. The substitute amendment defines “Native American cultural patrimony” as an object with significant historical, traditional or cultural importance and which is central to the culture of an Indian tribe or to Native Hawaiians. The Committee intends this term to refer to only those items that have such great importance to an Indian tribe or to the Native Hawaiian culture that they cannot be conveyed, appropriated or transferred by an individual member. Objects of Native American cultural patrimony would include items such as Zuni War Gods, the Wampum belts of the Iroquois, and other objects of a similar character and significance to the Indian tribe as a whole.”[10]. NAGPRA Senate Report 101-473 (1990)

Federal Lands

The new NAGPRA language states:

“For purposes of this definition, control refers to lands not owned by the United States Government, but in which the United States Government has a sufficient legal interest to permit it to apply these regulations without abrogating a person’s existing legal rights. Whether the United States Government has a sufficient legal interest to control lands it does not own is a legal determination that a Federal agency must make on a case-by-case basis. Federal lands include:

(1) Any lands selected by, but not yet conveyed to, an Alaska Native Corporation or groups organized under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (43 U.S.C. 1601 et seq.);

(2) Any lands other than Tribal lands that are held by the United States Government in trust for an individual Indian or lands owned by an individual Indian and subject to a restriction on alienation by the United States Government; and

(3) Any lands subject to a statutory restriction, lease, easement, agreement, or similar arrangement containing terms that grant to the United States Government indicia of control over those lands.” (our emphasis)

Hawaiian claims/land definitions

View of the ahupuaʻa of Oʻahu’s south and east side. CCA-SA 3.0 license.

There have always been issues with respect to the classification of the wide variety of Native Hawaiian Organizations for NAGPRA purposes. Native Hawaiian Organizations are not permanently recognized, as federally recognized Native American tribes are. Once granted Native Hawaiian Organization status, they must request renewal every 5 years. Native Hawaiian Organizations range in size and scope from the State of Hawaii’s Office of Hawaiian Affairs[11] (which serves and represents the interests of Native Hawaiians, but which the U.S. Supreme Court has held cannot be made up exclusively of Native Hawaiians) to small cultural and folklore organizations, schools, and Homestead Associations.

Full map of the ahupuaʻa of Oʻahu, Data from State of Hawaii, Author Sn1per, 27 November 2011.

Under the proposed new ‘geographical affiliation’ rules, the Native Hawaiian organization with the closest cultural affiliation, and thus able to claim cultural objects as well as human remains, is defined under the following hierarchy, based upon the concepts of ‘ohana (a Hawaiian term meaning “family“ in an extended family sense, including blood-related, adoptive or intentional) and ahupua’a (defined by the DOI as “a land division in Hawai‘i usually extending from the uplands to the sea which traditionally was, and in some cases remains, self-sustaining or whose occupants were or are permitted a right to gather and access for subsistence, cultural, or religious purposes. In contemporary times, ahupua‘a is also considered a cultural resource management principle.”)

The new rules define both organizationally-based and geographically-based cultural affiliations for the hundreds of Native Hawaiian organizations holding temporary 5-year recognition, from nearest affiliation to most distant in a system that is not only mind-bogglingly complex and challenging to administer, but which could give, for example, a family, a small local school or cultural organization priority over a claim by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs or another major organization tasked with preservation of heritage. The order is:

- An ‘ohana that can trace an unbroken connection of named individuals to one or more of the human remains or cultural items, but not necessarily to all of the human remains or cultural items from a specific site.

- An ‘ohana that can trace a relationship to the ahupua‘a where the human remains or cultural items were removed and a direct kinship to one or more of the human remains or cultural items, but not necessarily an unbroken connection of named individuals.

- An organization with affiliation only to the earlier occupants of the ahupua‘a where the human remains or cultural items were removed, and not to the earlier occupants of any other ahupua‘a.

- An organization with affiliation to either: (A) The earlier occupants of the ahupua‘a where the human remains or cultural items were removed, as well as to the earlier occupants of other ahupua‘a on the same island, but not to the earlier occupants of all ahupua‘a on that island, or to the earlier occupants of any other island of the Hawaiian archipelago, or (B) The earlier occupants of another island who accessed the ahupua‘a where the human remains or cultural items were removed for traditional or customary practices and were buried there.

- An organization with affiliation to the earlier occupants of all ahupua‘a on the island where the human remains or cultural items were removed, but not to the earlier occupants of any other island of the Hawaiian archipelago.

- An organization with affiliation to the earlier occupants of more than one island in the Hawaiian archipelago that has been in continuous existence from a date prior to 1893.

- Any other Native Hawaiian organization with affiliation. (§10.3(d)(2), 63241)

What is most likely to occur in such a complex system for making claims is that the organizations that more aggressively pursue claims are most likely to obtain authority over cultural objects as well as to receive human remains. This not unlike patterns sometimes seen in the Southwestern U.S., where 25 or more tribes may be listed as potential claimants on a NAGPRA Notice, but only a few tribes regularly make claims for any NAGPRA Notice.

New Regulations and Claims and the “Everything Back” Movement

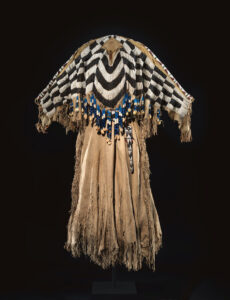

Tipi bag, ca. 1890, North Dakota or South Dakota, USA: Lakota/ Teton Sioux, The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art, Gift of Charles and Valerie Diker, 2019. Met description: This bag was made during the early reservation period, after the United States government outlawed the Lakota’s annual Sundance and instituted Fourth of July celebrations in its place. During this time, the American flag and interpretations of the Great Seal of the United States became popular beadwork motifs.

Legitimate questions about the effect of the proposed changes to NAGPRA also arise from an increasing shift by certain Native American activists toward demanding classification of broader and broader categories of objects, including items made for commerce, as “objects of cultural patrimony” and “sacred objects.” The proposed changes to NAGPRA come at a time when Native activist groups such as the Association on American Indian Affairs have urged aggressive claims for repatriation and demanded that tribal permission be sought for the transfer of objects long in legal circulation.[12]

Virtually all objects made by Native Americans, these groups have argued, should not only be returned by institutions receiving federal funds, but even when legally owned, they should not be transferred, donated or sold without the explicit permission of current tribal authorities.

These expanded claims would limit public access to art not previously deemed communally owned or sacred – even to artworks long recognized as secular and even made for commerce.

An example of this activism took place in 2018, after gifts and promised gifts of 91 masterworks to the Metropolitan Museum in NY from a private collection of Native American art resulted in a major expansion of the type of American art exhibited in the American Wing of the museum. The Met consulted extensively with tribal scholars in curating the exhibition including with Brian Vallo, an Acoma Pueblo member (and later Governor) who was also director of the Indian Arts Research Center (IARC) at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, NM.[13] The Metropolitan Museum’s exhibition did not feature objects generally understood as having a specifically ritual or sacred context.

Dress and belt with awl case, ca. 1870, made in Oregon or Washington, USA, Wasco, The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art, Gift of Charles and Valerie Diker, 2019. Garments of superior craftsmanship incorporating trade goods, such as this example, expressed personal identity and a family’s high status. The dress is accompanied by its own belt and awl case.

However, when the Met exhibition opened, Shannon Keller O’Loughlin, executive director of the Association on American Indian Affairs stated that, “Their first mistake was to call these objects art.”[14] She argued that prior to selling or donating Native American objects, owners must first confer with whichever of the 574 federally recognized tribes from which the objects originated. If the tribe claims the objects, the AAIA says they should be transferred to the tribe.

“Everything Back” has been the slogan of recent AAIA events, including its 2021 Repatriation Conference – and featured on the organization’s promotional t-shirts.[15]

A recent example of a claim on principle of “Everything Back” was made at the auction of the famous Roy H. Robinson Collection in October 2022, the AAIA sought to stop the sale of “ledger art” drawings by imprisoned warriors at Fort Marion in Florida between 1875 and 1878, made for sale. Ledger drawings have been in private and museum collections for 100 years but have never before been claimed as “cultural patrimony.”

Similarly, certain tribes and the AAIA have made recent claims that commercial kachinas made by Native carvers, signed and sold by them on eBay are “cultural patrimony”.

A Special Note – The Department of the Interior announced new and returning appointees to the NAGPRA Review Committee.

On November 22, Secretary Haaland appointed Edward Halealoha Ayau, Domonique deBeaubien, and Angela Garcia-Lewis, each for a four-year term. The new members join Timothy McKeown and Shelby Tisdale. Secretary Haaland reappointed Armand Minthorn for a two-year term.[16]

The appointment of Edward Halealoha Ayau to the NAGPRA Review Committee is a somewhat surprising one. Mr. Ayau is a Hawaiian attorney who was on the staff of Senator Daniel Inouye, a chief sponsor of the NAGPRA legislation passed in 1990. He founded one of the first Hawaiian Organizations to be accredited under NAGPRA, the Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei, or “Group Caring for the Ancestors of Hawaii.” After passage of NAGPRA, Ayau worked successfully to repatriate and rebury numerous Native Hawaiian human remains.

Bishop Museum – Hawaiian Hall, Photo by Daniel Ramirez from Honolulu, HI USA, 2015. Wikimedia Commons.

Then, in the mid-1990s, the Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei requested the repatriation of 83 objects from the 1905 Forbes Collection at Hawaii’s premier museum, the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum. The eight main objects in the Forbes Collection are considered among the most beautiful and important examples of Hawaiian carving in the world. In 2000, the museum’s vice-president turned over the Forbes Collection and 200 other objects to Ayau. The Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei group placed them in a cave in a remote location on Hawaii Island and sealed it. Litigation resulted after other Native Hawaiian claimants asserted their interest in the objects and demanded their return, which the Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei refused. The NAGPRA Review Committee also stated that the museum had made a mistake in transferring the items.

‘Uo ‘i’iwi, ‘i’iwi feather bundle from Hawaii, scarlet honeycreeper (Drepanis coccinea) feathers, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum accession 10559. Wikimedia Commons.

In September 2006, a U.S. District Judge ruled that the 83 artifacts must be returned to the Bishop Museum; Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei appealed and was denied. The judge suggested that the Hawaiian organization claimants should engage in a traditional mediation in order to resolve their differences. The judge also ordered Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai’i Nei director Edward Halealoha Ayau to be imprisoned for refusing to disclose the burial sites. Ayau spent three weeks in confinement and was released to participate in settlement negotiations. Later that September, it was reported that the 83 artifacts from Forbes Cave had been returned to Bishop Museum; a plaintiff confirmed the return had been completed and a settlement agreement was signed.[17]

Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai’i Nei is not currently listed among Native Hawaiian Organizations on the Department of the Interior Native Hawaiian Organization (NHO) Notification List,[18] updated October 14, 2022. Another organization, Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo, which names Mr. Edward Halealoha Ayau as director, appears on the list, having been originally registered on October 6, 2022. The Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo listing states that, “We are the successors of Hui Mālama I Nā Kūpuna O Hawaiʻi Nei who have continued to research, advocate, conduct, and fundraise the national and international repatriation and reburial of iwi kūpuna (ancestral bones), moepū (funerary possessions) and mea kapu (sacred objects) having completed 133 combined cases since 1990.” The successor organization directed by Mr. Ayau lists itself as having an interest in all islands, all Moku, and all Ahupua‘a.

See more: NAGPRA in Hawaii: Museum and Native Hawaiian Conflicts

The Department of the Interior requests comments on the proposed changes as follows:

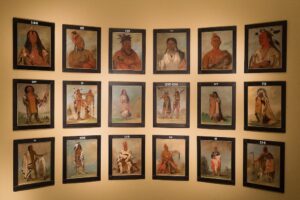

George Catlin, Portraits in Smithsonian American Art Museum, dates 1832, 1834, 1835, 1836. Top row, left to right: H’co-a-ah’co-a-h-cotes-min, No Horns on His Head, a Brave Nez Perce; Meach-o-shín-gaw, Little White Bear, a Distiguished Brave Kansas/Kaw; Háw-che-ke-súg-ga, He Who Kills the Osages, Chief of the Tribe issouria/Jiwere-Nutachi; Tís-se-woó-na-tís, She Who Bathes Her Knees, Wife of the Chief Cheyenne/Suhtai; Náh-se-ús-kuk, Whirlihg Thunder, Eldest Son of Black Hawk Sac and Fox; Stán-au-pat; Bloody Hand, Chief of the Tribe Arikara/Sahnish;

Middle row, left to right: Ha-na-tá-nu-maúk, Wolf Chief Head Chief of the Tribe Mandan/Numakiki;Ah-móu-a, The Whale, One of Kee-o-kúk’s Principle Braves Sac and Fox; Ah’-kay-ee-pix-en, Woman Who Strikes Many Blackfoot/Siksika; Two Young Men Menominee; Tsee-mount, Great Wonder, Carrying Her Baby in Her Robe Plains Cree; Wán-ee-ton, Chief of the Tribe Yanktonai Nakota;

Bottom row, left to right: Kotz-a-tó-ah, Smoked Shield, a Distiguished Warrior Kiowa; Nót-to-way, a Chief Iroquois/Haudensaunee; No-wáy-ke-súg-gah, He who Strikes Two at Once, a Brave Otoe/Jiwere-Nutachi; Cler-mónt, First Chief of the Tribe Osage/Wa-zha-zhe I-e; Wife of Kee-o-kúk Sac and Fox; Om-pah-tón-ga; Big Elk, a Famous Warrior Omaha;

Note: Tribal affiliations are given with historical associations first, followed by the current Native American preference, where it differs. Public domain.

The Department is committed to proactively working with all stakeholders to obtain feedback on topics in the recently published proposed rule to amend the NAGPRA implementing regulations at 43 CFR Part 10 (87 FR 63202, Oct. 18, 2022). Additional information on the proposed rule is available at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nagpra/regulations.htm. The Department will consult with the Review Committee during public meetings held during the open comment period. The Department is interested in receiving feedback from the public during public listening sessions or during the Review Committee meetings. If you would like to provide oral comment on the proposed rule, register at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1335/events.htm. You will be required to provide a written copy of your oral comment.

Public comment on the proposed changes must be submitted by January 17, 2023.

Public comments must be identified by the Regulation Identified Number (RIN) 1024-AE19, and must be submitted by one — and only one — of the following methods:

(1) via the Federal eRulemaking Portal: https://www.regulations.gov. Follow the instructions for submitting comments. Direct link to make comments is: NPS-2022-0004-0001.

(2) by mail to: National NAGPRA Program, National Park Service, 1849 C Street, NW, Mail Stop 7360, Washington, DC 20240. Attn: Melanie O’Brien, Manager, NAGPRA Rule Comments.

[1] Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act Systematic Process for Disposition and Repatriation of Native American Human Remains, Funerary Objects, Sacred Objects, and Objects of Cultural Patrimony, 43 CFR Part 10, Proposed Rule, Federal Register, Vol. 87, No. 200, Tuesday, October 18, 2022, 63202-63260

[2] If the library received federal funds, as it indirectly did through funds provided by the City of Medford, MA, which itself received federal funding as part of its budget, then it would have an obligation to inventory and contact potential tribal claimants. However, the “experts” quoted in the press incorrectly claimed that NAGPRA covered commercially made items and made numerous misleading statements about the illegality of selling similar items, which it should be noted are lawfully held in both private and public collections and found in numerous museum collections in the U.S. See, for example, Alexander Thompson, The Tufts Daily, December 5, 2018, https://tuftsdaily.com/news/2018/12/05/medford-cancels-auction-native-american-artifacts-federal-violations/

[3] According to the proposed NAGPRA regulations: “’Receives Federal funds’ means an institution or agency of a State or local government (including an institution of higher learning) directly or indirectly receives Federal financial assistance after November 16, 1990, including any grant; cooperative agreement; loan; contract; use of Federal facilities, property, or services; or other arrangement involving the transfer of anything of value for a public purpose authorized by a law of the United States Government. This term includes Federal financial assistance provided for any purpose that is received by a larger entity of which the institution or agency is a part. For example, if an institution or agency is a part of a State or local government or a private university, and the State or local government or private university receives Federal financial assistance for any purpose, then the institution or agency receives Federal funds for the purpose of these regulations.”

[4] For more examples of recent re-categorization of objects hitherto not considered sacred or communally owned, see Ron McCoy, “Is NAGPRA Irretrievably Broken?”, Cultural Property News, December 19, 2018, https://culturalpropertynews.org/is-nagpra-irretrievably-broken/ As McCoy notes:” “The museum’s Indian Arts Project was the creation of Arthur C. Parker, the institution’s part-Seneca director. Between 1935 and 1941, 31 Tonawanda Seneca men and women – joined the first year by 39 residents of the Senecas’ reservation at Cattaraugus – received fifty-cents an hour while creating 6,000 “wood carvings, beaded outfits, silver jewelry and other accessories, baskets, cornhusk dolls, and bottles, as well as more than 200 easel paintings illustrating ceremonies, traditional stories, historic events and daily activities of the people of the Reservation. They saw themselves as renewers and reclaimers of Seneca traditions and values….Parker hoped that the Indian Arts Project would nurture craftswork that could help the participants continue to earn a living. Only a few, however, continued with painting or carving that could be sold to collectors. Their work remains one of the best documented collections of Seneca materials in the world.” “The Indian Arts Project (1935-1941),” Rochester Museum & Sciences Center (n.d.: Rochester, NY), http://www3.rmsc.org/museum/exhibits/online/lhm/IAPmain.htm. One of the participants was famed author, mask carver and Cattaraugus native Jesse Cornplanter [1889-1957], who “provided designs and models for false face masks that the other carvers followed

[5] Kate Fitz Gibbon, NAGPRA in Hawaii: Museum and Native Hawaiian Conflicts, Cultural Property News, May 1, 2019, https://culturalpropertynews.org/nagpra-in-hawaii-museum-and-native-hawaiian-conflicts/.

[6] U.S. Department of the Interior, “Interior Department Takes Next Steps to Update Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, October 13, 2022, https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/interior-department-takes-next-steps-update-native-american-graves-protection-and-1

[7] Supra n. 6. U.S. Department of the Interior, “Interior Department Takes Next Steps to Update Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, October 13, 2022, https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/interior-department-takes-next-steps-update-native-american-graves-protection-and-1

[8] Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act Systematic Process, Federal Register, Vol. 87, No. 200, October 18, 2022, p 63215.

[9] Id. at 63213.

[10] Providing For The Protection Of Native American Graves And The Repatriation Of Native American Remains And Cultural Patrimony, Senate Report 101-473 (1990), September 26, 1990, 5, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nagpra/upload/SR101-473.pdf

[11] The State of Hawaii’s Office of Hawaiian Affairs serves and represents the interests of Native Hawaiians, but is not exclusively administered by Native Hawaiians. The U.S. Supreme Court has held that Native Hawaiians

[12] See, for example, Association on American Indian Affairs, press release, Dealers in Native American Cultural Heritage Choose Profit Over Anti-Racism, April 5, 2021, http://www.indian-affairs.org/uploads/8/7/3/8/87380358/2021-04-05_auction_house_anti_racism.pdf

[13] See Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection, https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2018/art-of-native-america-diker-collection/community-perspectives, and The Met, Art of Native America, installation tour, series of 9 videos, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z3U6ga0iVVk

[14] Gabriella Angeleti, Native American group denounces Met’s exhibition of indigenous objects, November 6, 2018, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2018/11/06/native-american-group-denounces-mets-exhibition-of-indigenous-objects

[15] Association on American Indian Affairs, 7th Annual Repatriation Conference, https://www.indian-affairs.org/7thannualconference.html

[16] National Park Service, Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, Members, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nagpra/members.htm

[17] Kate Fitz Gibbon, NAGPRA in Hawaii: Museum and Native Hawaiian Conflicts, Cultural Property News, May 1, 2019, https://culturalpropertynews.org/nagpra-in-hawaii-museum-and-native-hawaiian-conflicts/.

[18] US. Department of the Interior, Office of Native Hawaiian Relations, Native Hawaiian Organization Notification List, maintained by the Office of Native Hawaiian Relations, Updated October 14, 2022, https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/nhol-complete-list.pdf.

National Museum of the American Indian, 2005 Powwow. MCI Center. Photo Walter Larrimore, 15 August 2005, public domain.

National Museum of the American Indian, 2005 Powwow. MCI Center. Photo Walter Larrimore, 15 August 2005, public domain.