While NAGPRA is the most important U.S. legislation to address past abuses regarding the collecting of human remains and artifacts from indigenous peoples, its history with respect to Native Hawaiians is less widely known than for Native American tribes.

‘Uo ‘i’iwi, ‘i’iwi feather bundle from Hawaii, scarlet honeycreeper (Drepanis coccinea) feathers, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum accession 10559. Wikimedia Commons.

Most discoveries of artifacts and human remains in Hawaii occur as a result of development projects that unearth individual burials or antique cemeteries. These finds are usually dealt with by Hawaiian state government agencies, which often negotiate returns and reburials with local organizations.

There have been relatively few returns of Hawaiian remains and objects under NAGPRA. When these returns take place, they are distributed to federally recognized Native Hawaiian Organizations. The most commonly contacted organizations are the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, the five Island Burial Councils, and the Department of Hawaiian Homelands.

The relationships between Hawaiian organizations over NAGPRA returns are characterized by lively controversies between different interest groups, communities, and even families over control of remains and Hawaiian cultural objects. Their conflicting claims impact how NAGPRA operates in Hawaii. Often, NAGPRA’s official notices acknowledge the difficulty of identifying the correct recipients for returns, stating that repatriation “may proceed after that date when the affiliated Native Hawaiian organizations have mutually agreed upon a resolution,” or when “the dispute is otherwise resolved pursuant to NAGPRA or as ordered by a court of competent jurisdiction.”

The first Hawaiian NAGPRA repatriation controversy was replete with highly publicized accusations between the parties, made in the press and in the courts. Some of the conflicts over how remains and artifacts should be dealt with have never been resolved, and continue to reverberate through other Hawaiian issues. They echo in grassroots movements to obtain recognition of Native Hawaiians as ‘tribes,’ to assert indigenous rights, and even in political campaigns to make Hawaii an independent nation.

A brief introduction of NAGPRA’s Hawaiian history may be useful in understanding current demands for recognition of Native rights in Hawaii.

Queen Kapiolani sitting on chair draped with feather cloak. David Kalakaua (1888) The Legends and Myths of Hawaii: The Fables and Folklore of a Strange People, C.L. Webster & Company, p. 318. Wikimedia Commons.

This article will not discuss the complex issues of race-based versus political categories under federal Indian law and how their adoption may change NAGPRA. NAGPRA is founded on the federal-Indian trust relationship, which is both treaty and legislation based; it does not treat Indian tribes as forming a racial category, but rather as sovereign entities.

The key to understanding NAGPRA processes in Hawaii is that Native Hawaiians are not currently organized under “tribal” categories and do not receive federal benefits specifically designated for “tribes.” Instead, a federal registration process identifies Native Hawaiian organizations that should be notified or consulted with when required under laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), and NAGPRA. A list of current Hawaiian entities is maintained at the Office of Hawaiian Relations (OHR) within the Office of the Secretary, U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI).[1] Native Hawaiian organizations range from Chamber of Commerce groups working to enhance economic opportunities for Hawaiian people, to school programs supporting traditional culture, hula dance organizations, Hawaiian language preservationists, and environmental groups. All listed Native Hawaiian Organizations must reapply after five years or they are delisted from the federal register.

The First Hawaiian NAGPRA Controversy

The accusations of self-dealing, theft and breach of fiduciary duty in the first contested NAGPRA case in Hawaii illustrate some of the practical difficulties and risk to objects in applying NAGPRA when there are conflicting claims of ownership by Native peoples. Key to this tangled controversy is the nature of a Native Hawaiian Organization, defined broadly under NAGPRA as an organization that has as a “stated purpose the provision of services to native Hawaiians.”[2]

Edward Halealoha Ayau, a Hawaiian attorney who was on the staff of Senator Daniel Inouye, a chief sponsor of the NAGPRA legislation passed in 1990, founded one of the first Hawaiian Organizations to be accredited under NAGPRA, the Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei, or “Group Caring for the Ancestors of Hawaii.”

After passage of NAGPRA, Ayau worked to repatriate and rebury numerous Native Hawaiian human remains. Then, in the mid-1990s, he requested the repatriation of 83 objects from the 1905 Forbes Collection at Hawaii’s premier museum, the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum. The eight main objects in the Forbes Collection are considered among the most beautiful and important examples of Hawaiian carving in the world.

‘Ahu’ula, Hawaiian feather cloak, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, accession 00323, Photo by Hiart, 2017. Wikimedia Commons.

Although many Hawaiian experts hold that Hawaiians were very rarely buried with funerary objects, Ayau asserted that they were actually funerary objects because they had been discovered in a cave that also held some human remains, and that they were illegally taken, although there was no law prohibiting it at the time.

In 2000, the museum’s vice-president turned over the Forbes Collection and 200 other objects to Ayau. The Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei group placed them in Kawaihae Caves, in a remote location on Hawaii Island and sealed the cave.

The Royal Hawaiian Academy of Traditional Arts and Na Lei Alii Kawananakoa, two other Hawaiian organizations listed under NAGPRA, sued the Bishop Museum and Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei for inappropriately distributing the objects in violation of NAGPRA. Altogether, thirteen Native Hawaiian organizations joined the group claiming cultural affiliation and persuaded the NAGPRA Review Committee to hold hearings on the transfer. A new director of the Bishop Museum attempted to recall the objects, stating that he was concerned about whether they remained in the cave and about their condition. The Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei attempted to halt the NAGPRA Review Committee’s consideration of the matter, saying it had not been properly notified and that the “National Park Service is engaged in an organized effort to subvert the intent of Congress by obstructing implementation of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.”[3] The NAGPRA Review Committee stated that the museum had made a mistake in transferring the items.[4] There was considerable controversy and public unhappiness with the role of the museum, and accusations of racist behavior by a “white” museum. The arguments for and against the funerary character of the objects were published in Hawaiian newspapers in May 2003. In September 2003, the Department of Hawaiian Homelands refused the Bishop Museum’s request to go into the Kawaihae Cave Complex to retrieve the objects, setting the stage for litigation to recover the objects for distribution to the thirteen claimants. The museum’s vice-president was fired after accusations of conflict of interest involving sympathies toward Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei.

Chart of the Sandwich Islands. printed by G. Nicol and T. Cadell for the 1785 edition of Captain James Cook and James King’s, A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean…in the Years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779, and 1780. In the lower left there is a large inset of Karakakooa Bay and the villages there. It was here that Cook was killed by angry Hawaiians. Wikimedia Commons.

The museum issued a position paper stating that it also was a Native Hawaiian organization, having been founded during the Hawaiian Kingdom, and was a steward for the protection of artifacts which were given to it for safekeeping by members of the noble Hawaiian families. This engendered further political controversy. The Bishop Museum’s request to be treated as a Native Hawaiian organization was opposed by Senator Inouye and others. The museum board later voted to withdraw the request. Meanwhile, federal agents had been stationed by at least one of the cave locations.

Also in 2004, reports circulated that several items from another early collection made in the mid-1800s by Joseph Swift Emerson, and repatriated by the Bishop Museum and Peabody Essex Museum to Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei in 1997, had appeared on the market in Hawaii, still bearing their museum labels. A collector who saw the items contacted federal authorities, who began an investigation. Some of the claimants sought to enter the caves and ascertain if the repatriated items were still there. Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei denied having anything to do with removing or selling artifacts. A few weeks later, reporters found one of the caves lying open. The boulders that had blocked access had been removed. State officials stepped in to seal the caves. In March 2006, two Hawaii island men were charged and plead guilty to conspiring to take the Peabody Essex and Bishop Museum artifacts from the Kanupa Cave.

‘Ahu ‘ula, feather cape from Hawaii, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum accession 07766. Photo by Hiart, 2017. Wikimedia Commons.

In September 2006, a U.S. District Judge ruled that 83 artifacts buried in two Big Island caves must be returned to the Bishop Museum; Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei appealed and was denied. The judge suggested that the Hawaiian organization claimants should engage in a traditional mediation in order to resolve their differences. The judge also ordered Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai’i Nei director Edward Ayau to be imprisoned for refusing to disclose the burial sites of the Forbes Cave items, and named a structural engineering company to assess the stability of the Forbes Cave. Ayau spent three weeks in confinement and was released to participate in settlement negotiations.

On September 5, 2006 it was reported that the 83 artifacts from Forbes Cave had been returned to Bishop Museum; a plaintiff confirmed the return had been completed. In a settlement agreement, the cost of returning the items was apportioned half to the museum and half to Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei.

The organization Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawaii Nei was officially dissolved on December 20, 2014. It does not appear in the most recent May 2018 Department of the Interior Native Hawaiian Notification List. However, despite no longer being a recognized recipient for NAGPRA returns, it appears to still be accepting international repatriations of human remains. In November 2017, the State Museums of the Free State of Saxony in Germany worked through the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and the Hui Mālama I Nā Kūpuna ‘O Hawai’i Nei to return the remains of indigenous Hawaiians that had been removed from burial caves in Hawaii between 1896 and 1902, and subsequently sold to the Museum of Ethnology in Dresden, now incorporated into the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden.

Dole Pineapple Company 1950. Pictorial map of Hawaii by the artist Joseph Feher. The map shows eight major Hawaiian Islands with decorative elements including scenes of Hawaiian life, tropical fish, ships, volcanoes, and tourists. Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Native Hawaiian Organization Notification List. Fed. Reg. 186 (Sept, 26, 2007).

[2] 43 CFR 10.2(b)(3)(i)Native Hawaiian organization means any organization that: (A) Serves and represents the interests of Native Hawaiians; (B) Has as a primary and stated purpose the provision of services to Native Hawaiians; and (C) Has expertise in Native Hawaiian affairs.

[3] A valuable guide to and chronology of this controversy is Kenneth R. Conklin, The Forbes Cave Controversy During and After The NAGPRA Review Committee Meeting of May 9-11, 2003, including official findings of the review committee published August 20, 2003 and Bishop Museum position paper of June 30, 2004., http://www.angelfire.com/hi2/hawaiiansovereignty/nagpraforbesafterreview.html

[4] NAGPRA National Review Committee Meeting In St. Paul, Minnesota May 9-11, 2003 (Focusing On Forbes Cave Controversy) — Findings, Recommendations, And Minutes Of The Meeting (Published August 20, 2003), http://www.angelfire.com/hi2/hawaiiansovereignty/nagpranatlmtngmay2003.html.

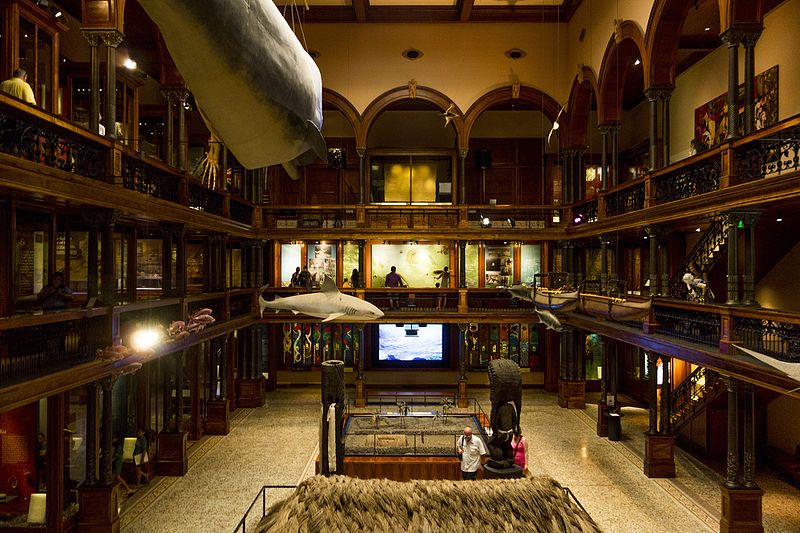

Bishop Museum - Hawaiian Hall, Photo by Daniel Ramirez from Honolulu, HI USA, 2015. Wikimedia Commons.

Bishop Museum - Hawaiian Hall, Photo by Daniel Ramirez from Honolulu, HI USA, 2015. Wikimedia Commons.