North of Beirut, overlooking a beautiful jetty on the Mediterranean Sea is Lebanon’s newly minted Nabu Museum. The museum was founded by three Middle Eastern businessmen in order to “provide a tranquil space for the preservation and creative pursuit of art and culture in a region of seemingly constant turmoil and strife.” From the thoughtful integration of architecture into landscape and the harmonious contextualizing of ancient and contemporary art, the museum appears to have met its goal.

Three Friends with an Eye Toward “Giving Back”

Friends since their youth, successful businessmen Jawad Adra, Fida Jdeed, and Badr El-Hage began to ask themselves, “How can we give back?”

Long time art and antiquities collector and spokesperson for the Nabu Museum, Jawad Adra is the founder and managing partner of Information International SAL, a Beirut based information research company. In 1997 he founded the Social and Cultural Development Association (INMA), an NGO that focuses on community building through providing healthcare, job skill training and education with an environmental and cultural bent in villages in rural Lebanon. Adra is currently the president of that organization.

Fida Jdeed is the Nabu Museum’s Syrian co-founder and a partner at Information International, and Badr El-Hage is a Lebanese entrepreneur, writer and expert on 19th century Middle Eastern photography. He is the founder of Folios Limited, a rare book business based in London.

Realizing that governments in the region were “busy battling troubled economies and poverty,” and unable to support additional cultural activities, Jawad Adra, Fida Jdeed, and Badr El-Hage pooled their expertise, financial resources, art, antiquities and book collections, and the Nabu Museum was born.

A Unique Architectural Accomplishment

Nabu Museum, https://www.nabumuseum.com/home.

The Nabu Museum collection is housed in a multistory, weathering steel, rusty-orange patinated, stylized cuboid structure. The building would be heavy and foreboding without a central panel of glass that allows natural light in and provides the visitor with a view of the museum interior as well as a dramatic window onto the sea, right through the building.

Iraqi artists Dia Azzawi and Mahmoud Obeidi worked with Nabu’s founders in the museum’s architectural design. In an October 16th interview by Maghie Ghali for the Lebanese Daily Star, Antiquities Mingle with Modernism, Adra said, “[They] decided to use weathered steel to create the façade of the building…” “which has a connection to the sea, as it changes color with humidity.” “The final choice of material has a poetic and practical meaning as it becomes the building’s form, shape and color at once.” Adra noted that the “forms were informed by Azzawi’s interest in calligraphy as abstract semiotic elements.”

In November 2018, the rooftop café will open: that will also be an art experience. As Adra explained to Lizzie Porter in a October 14th article Lebanon celebrates 2,000 years of creativity with new Nabu Museum, “Diners will sit in the shadow of Ford 71, an installation by Iraqi-Canadian artist Mahmoud Obaidi. Inspired by the 2003 United States invasion of Iraq, a military vehicle in bronze and cor-ten steel is topped with a Mesopotamian statuette and its trunk is filled with ancient columns. It’s a wry comment on occupation.”

An Eclectic Collection Spanning Thousands of Years

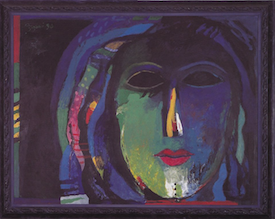

Dia Al-Azawi, “Eshtar,” Nabu Museum.

The museum opened on September 22, 2018. Its first exhibit is “Millennia of Creativity”, curated by Pascal Odille. Modern art and ancient antiquities from Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Egypt and Yemen are combined in the exhibition, in order to tell the history of the Roman, Greek, Byzantine, Phoenician, Mesopotamian, and contemporary cultures of the Middle East. It is both a story of evolution and what Odille sees as a sort of “confrontation between different ages.” As Odille explained to Porter, “We cannot build a future without looking back at what happened in the past.”

Twentieth century Lebanese artist Katya Traboulsi’s sculpture of a mortar missile adorned with hieroglyphs, and millennial old “Ushabti” figurines, meant to transform into servants for the Egyptian elite in the afterlife, sit in close proximity in the exhibition. And, as Porter noted, “2,000-year-old alabaster statues from south Arabia and Babylonian tablets displaying some of the earliest forms of writing are exhibited alongside 20th-century artworks by Lebanese, Iraqi and Palestinian artists.”

The permanent collection and the items in the current exhibit are from the acquisitions of the museum’s founders. The majority come from the collection of Jawad Adra, who purchased Middle Eastern antiquities at Christie’s in New York, Bonham’s in London and from a variety of Parisian auction houses. Adra also provided a number of contemporary works from local and regional artists such as Shafic Abboud, Amin al -Bacha, Helen Khal, Dia Azzawi, Shakir al – Said, Omar Onsi, Mustapha Farroukh, Ismail Fattah, Adam Henein, Khalil Gibran, Paul Guiragossian and Mahmoud Obaidi. The museum also holds a unique collection of works by Saliba Douaihy.

In 2016, Lebanon passed a law requiring all antiquities to be registered with its government’s cultural ministry. Although Adra has registered most of his collection, according to Lizzie Porter, “Adra admits that he has not always known the exact provenance of objects purchased, but he thinks putting collections on public display is one of the best ways to tackle the theft and smuggling of antiquities. “ He told Porter, “If everyone did what we have done, smuggling and illicit trading would become much more difficult, because you become accountable for every object.”

The naming of the museum

The museum is named after Nabu, the ancient Mesopotamian patron god of literacy, the rational arts, scribes and wisdom. Nabu is well known as the god of cuneiform writing. The museum holds a large collection of tablets dating from 2330 to 540 B.C.E. As the museum website states, “Cuneiform tablets are important archival records of our ancient past.” These tablets include “literary works and extensive social and economic records, that together provide detailed and often new, information on the history and culture of the Sumerians and Babylonians of Mesopotamia.”

In tribute to Nabu (and with the assistance of Badr El-Hage) the museum library houses an extensive collection of books on art, archaeology, history, and geography, along with a collection of rare manuscripts.

As the god of literacy and wisdom, Nabu was linked by the Romans with Mercury, and by the Egyptians with Thoth.

Bringing regional access to an under-served public

The three founders intentionally chose not to locate the museum in Beirut, but 50 miles north of the capital, in el-Heri village. Entry to the museum is free. There are plans for instituting workshops for schools and residencies for artists in the village.

There is a reason for this focus on rural accessibility. According to Adra, fewer than 25 percent of Lebanese adults have visited Lebanon’s national museum, and even fewer – approximately 14 percent – have read books outside of what was required for their formal education. “With numbers like these, one can argue that there isn’t much demand for culture in this country. However, once people learn to appreciate art through exposure to it, galleries and museums then become desired destinations.” In a country without easy access from outside Beirut to museums, placing a museum, with free admission, at this distance from Beirut will increase regional access to art and culture. No doubt the god Nabu would approve.

Palmyran funerary relief, Collection of Jawad Adra. Private collection in Nabu Museum, El Heri , Batroun, Lebanon.

Palmyran funerary relief, Collection of Jawad Adra. Private collection in Nabu Museum, El Heri , Batroun, Lebanon.