Introduction

Several days after the deadline for submission of public testimony on a request from Morocco for import restrictions under the Cultural Property Implementation Act, the State Department finally published a ‘summary’ of the request. The following extracts from the Committee for Cultural Policy’s and Global Heritage Alliance’s testimony, which by necessity was submitted before publication of the request, addresses the lack of evidence for the need for an agreement and the request’s failure to meet the requirements of the law. When the Morocco Public Summary was finally made available, it did not provide evidence of any current looting or otherwise attempt to satisfy the legal requirements.

Some words of explanation: The 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA) is the U.S. implementing legislation for the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. The CPIA was intended to balance U.S. interests in free trade and access to art with source county claims to heritage and the need to protect archaeological sites from looting. In the CPIA, Congress reserved judgment on the scope of import restrictions to the U.S. Instead, the law allows targeted export restrictions on materials currently threatened by looting and requires that important market nations act together to similarly block imports.

The Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) provides recommendations under the CPIA. In order to recommend import restrictions, CPAC must find that the request satisfies all four requirements set forth under the law. The requirements are:

- The cultural patrimony of the State Party is in jeopardy from the pillage of archaeological or ethnological materials of the State Party.

- The State Party has taken measures to protect its cultural patrimony.

- The application of the requested import restriction would be applied at the same time by other nations with a significant import trade in the restricted objects, and would have a substantial effect in deterring a serious situation of pillage – – and other remedies are not available.

- The application of the import restrictions is consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.

Excerpts from Testimony by Committee for Cultural Policy[1] and Global Heritage Alliance.[2] at the meeting of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee, October 29, 2019, refs. Federal Register: Oct. 2, 2019 (Volume 84, Number 191 (Page 52551):

Due process not served in hearing set with only two weeks notice

Key U.S. stakeholders, including museum organizations, heritage associations, art collectors and religious communities, especially religious minorities whose families lived in Morocco, have once again been denied a real opportunity to voice their concerns about the proposed MOU with Morocco.

In 2017, in its request for commentary on an MOU from Libya, the Department of State effectively excluded important stakeholders from being heard by providing a comment period of less than two weeks (which included the 4th of July weekend). At that time, representatives of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs assured members of the public that this would not happen again.

Jewish cemetery, Tangier, Morocco, photo by Diego Delso, diego.delso, 11 December 2015, license CC BY-SA. Wikimedia Commons.

The current Morocco request allowed only two weeks for comment and these two weeks included both a federal holiday and the Jewish High Holiday of Yom Kippur. This rushed scheduling has harmed the ability of museums and minority communities to consult with their members and to provide a full and considered response.

The State Department cannot claim that it is unaware of the specific concerns of the Jewish community for whom this scheduling is especially difficult. Eighteen prominent Jewish organizations have raised concerns about overbroad and legally untenable cultural property agreements granted to MENA countries in a December 8, 2018.[3]

The Department of State Has Failed to Provide Any Summary of the Morocco Request

Both the Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance support the Congressionally mandated application of the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA).[4] However, both organizations object strongly to the State Department’s failure to publish a complete text of the request, much less a Summary.

The Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance respectfully request that the Morocco request for import restrictions be held over for a later meeting of CPAC, that the full text of the Morocco request be supplied to the public, and that the public be given an opportunity to address the range of materials sought to be restricted and the chronological scope of the request.

Morocco has provided no information on what it seeks import restrictions on. The mere fact that Morocco has made a “request” is not sufficient for a public response. A publicly available statement of the evidence meeting the statutory requirements – and the ability to challenge or question that evidence – is necessary in order to determine whether the request actually meets the criteria set by Congress in the Cultural Property Implementation Act.

Wall of Tangier, Morocco, photo by Diego Delso, diego.delso, 11 December 2015, license CC BY-SA. Wikimedia Commons.

Morocco has not even stated whether it is making a “regular” request pursuant to 19 U.S.C. § 2602 or an “emergency” request pursuant to 19 U.S.C. § 2602(e). Different findings must be made for each under the law.

It is strange that the Cultural Property Advisory Committee requests public commentary be limited to the four determinations[5] set forth in the CPIA without requiring foreign governments to make any showing whatsoever under these key provisions of the Act.

Blanket Restrictions Were Never Contemplated by Congress

The Federal Register Notice announcing the Morocco Request states that Morocco is seeking import restrictions on “archaeological and ethnological material representing Morocco’s cultural patrimony.”[6] Without further elaboration, this implies that Morocco is seeking restrictions on a very broad range of items, at least by date. Blanket restrictions on objects that are neither currently threatened by looting nor demonstrated to be illicitly trafficked in the U.S. were never contemplated by Congress, either in the legislation or in the Congressional hearings on the CPIA.

On the contrary, Professor James Fitzpatrick, an expert on cultural property law who was personally involved in the negotiations in Congress that resulted in passage of the CPIA, has noted,

“…On their face, wall-to-wall embargoes fly in the face of Congress’ intent.[7] Congress spoke of archeological objects as limited to “a narrow range of objects…”[8] Import controls would be applied to “objects of significantly rare archeological stature…As for ethnological objects, the Senate Committee said it did not intend import controls to extend to trinkets or to other objects that are common or repetitive or essentially alike in material, design, color or other outstanding characteristics with other objects of the same type…[9]”

Morocco Has Provided No Evidence That Its Cultural Property is Currently Subject to Looting

The first determination that must be met under the CPIA is that the cultural patrimony of the State Party is in jeopardy from the pillage of archaeological or ethnological materials of the State Party. Morocco has not provided evidence that archaeological or ethnological materials are currently subject to looting, and thus does not meet the requirements set by Congress in the Cultural Property Implementation Act. Morocco has entirely failed to satisfy the determination required by 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(A), showing that each type of objects for which import restrictions are sought is in jeopardy from pillage. No list of specific items subject to current looting and no evidence of pillage has been presented.

It is worth noting that except for articles describing the looting and defacement of prehistoric rock carvings, particularly in the 1990s, there is almost nothing in news coverage in the last decade on looting or smuggling of art or antiquities from Morocco.

Morocco Has Provided No Evidence That Any Illegal Trafficking Has Taken Place in the U.S.

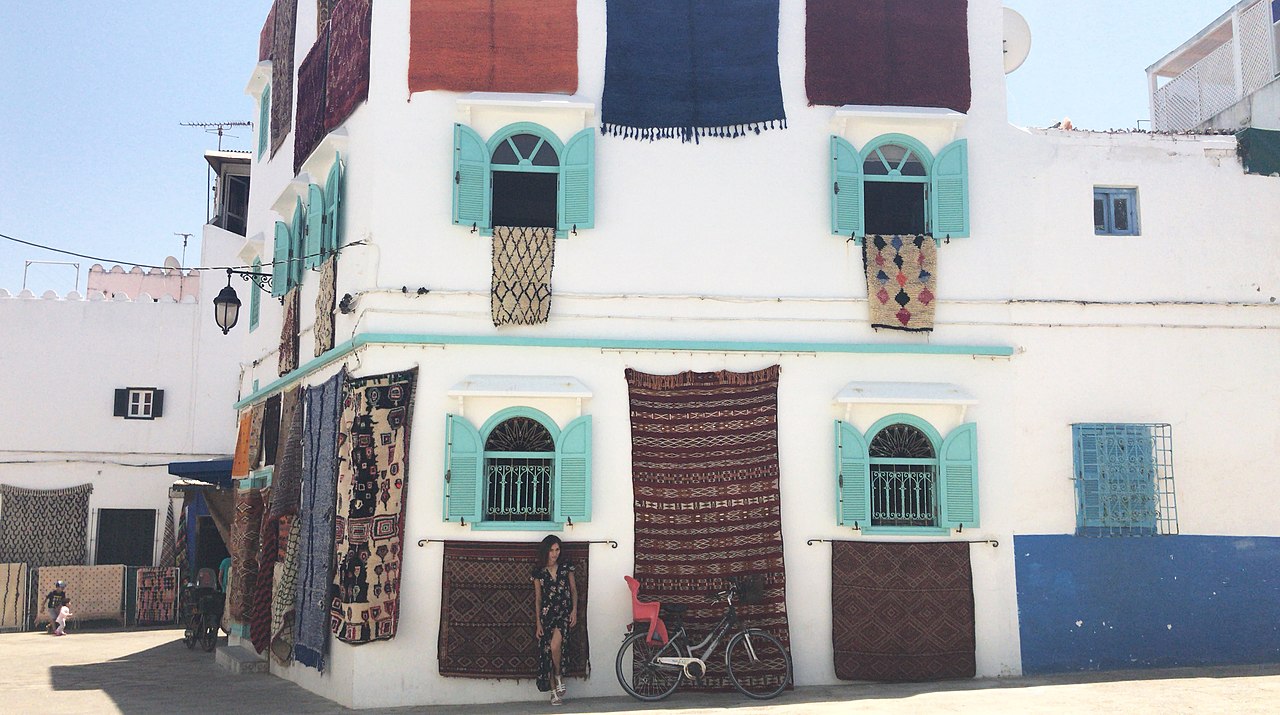

Carpet sellers, Aït Benhaddou, Morocco, photo by Grand Parc-Bordeaux, France, 22 June 2013, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Moroccan artworks found in the U.S. market are varied, but not often of significant value. There was no indication that items we located on eBay or in auction house records, virtually all of which are available online and which are equally accessible by the government of Morocco, appear to have been illicitly trafficked. Moroccan artworks sold at art auctions have either been manuscripts or photographs or Orientalist paintings with European provenance histories. We looked at the eBay market in supposedly Moroccan materials and found among the fifty most expensive items a number of Jewish manuscripts (from $450-$49,000, but almost all priced at less than $1000) being offered by sellers in Israel. There were also a number of ordinary beads and jewelry items. Such jewelry items are regularly sold to tourists visiting Morocco.

There is a significant eBay market in Moroccan carpets. Neither these nor Moroccan textiles and costumes are restricted from ordinary export, as attested by the thousands of carpet shops in the Middle East, Europe, Asia and the U.S. regularly being restocked with similar inventory. These are also not restricted in ownership or trade within Morocco.

The only items from Morocco being sold in popular venues that are restricted from export under Moroccan law are fossils. Fossil items and prehistoric rock carvings from Morocco were available in great numbers in the European and U.S. markets of the 1990s and early 2000s, and many are still being offered for sale.

Regarding the Submission of Ms. Katie Paul

With respect to this determination, we note that Ms. Katie Paul of the Athar Project has submitted a comment to CPAC alleging a significant illicit trade in objects from Morocco. Ms. Paul’s research identifies seventeen objects or lots that she identifies as illegally trafficked between 2016 and 2019. To be more accurate, these are items being offered for sale on Facebook; there is no knowing if they were actually illegally owned (i.e. found in illicit excavations) in Morocco, or if they actually fit into the categories of items that may be legally possessed but not exported from Morocco, or if they were actually ever sold. However, let’s assume the worst, that all items were being illegally sold.

Unfortunately, these images are very fuzzy and do not permit serious analysis. Of the items shown, however, two lots are clearly elephant ivory carvings of the tourist market type that cannot under any circumstances be imported commercially into the U.S. under both USF&W Director’s Order 210 and under the African Elephant Conservation Act, reducing the number to fifteen objects or lots of objects being offered for sale out of Morocco within a three year period.[10] Several items are jewelry of low quality from the 1970s or later, regardless of what their optimistic sellers claim about their being antique. These are not illicit or looted, or even very old.

We will not question the authenticity of any of the supposedly ancient manuscripts she depicts (although similar fakes of Jewish materials are notoriously prevalent in MENA markets) or cavil about the relatively recent types of Islamic calligraphy shown (similar items were being made throughout the Middle East up to the early 20th century). Although we agree that dealing in any illicit materials is reprehensible, we submit that ten or fifteen sales in three years is not indicative of a looting crisis.

Self-Help Requirements

Carpet Bazaar, antique costumes and rugs on sale, Essaouira, Morocco, Photo by Daniel Csörföly, September 2004, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

The Kingdom of Morocco has not provided information to the public demonstrating its commitment to preserving its monuments and taking steps to reduce trafficking. Congress is on record stating that parties to MOUs are required to take significant self-help measures and that these need to be considered when judging the effectiveness and continuation of MOUs. The House Appropriations Subcommittee included language in a recent State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Appropriation Bill urging CPAC to “consider the annual national expenditures on securing and inventorying cultural sites and museums in its annual reviews of the effectiveness of MOUs, as well as during the reviews required by the CPIA for extension of an MOU.”

The Appropriations Subcommittee also indicated that they will hold CPAC responsible: “The Cultural Properties Implementation Act (CPIA) requires countries participating in MOUs restricting cultural property take significant self-help measures… The Committee also requests the Secretary of State review the feasibility of collecting and reporting on the cost of measures taken by partner countries in support of their cultural property MOU with the United States and be prepared to report on such review…”

Without making significant self-help actions part of the discussion, the determination that Morocco has done its best to ameliorate looting cannot be made.

Import Restrictions Must Be of Substantial Benefit in Deterring a Serious Situation of Pillage

Another measure of whether an MOU with the U.S. would reduce the jeopardy of pillage is whether there is a market in pillaged material in the state that is being asked to impose import restrictions. Section 303(a)(1)(C) of the CPIA states that U.S. import restrictions may be implemented only if:

“the application of the import restrictions set forth in section 307 with respect to archaeological or ethnological material of the State Party, if applied in concert with similar restrictions implemented, or to be implemented within a reasonable period of time, by those nations (whether or not State Parties individually having a significant import trade in such material, would be of substantial benefit in deterring a serious situation of pillage…)”

The Moroccan request fails to show that the United States is a significant market for recently looted Moroccan antiquities. The Moroccan request does not provide any data on recent U.S. imports of any of these materials. It does not show that there is any significant market for recently looted Moroccan antiquities anywhere. Nor does it demonstrate that U.S. import restrictions will have a significant effect in preventing current looting in Morocco.

No Showing that Import Restrictions Would Be In the Interest of the International Community

Old American Legation Museum, Tangier, Morocco, photo by Diego Delso, diego.delso, 11 December 2015, license CC BY-SA. Wikimedia Commons.

The last showing under the CPIA’s fourth determination is that the application of the import restrictions is consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes. Although CPAC has often accepted having traveling exhibitions as meeting an extremely low threshold of what constitutes being in the interest of the interchange of cultural property, Morocco has provided no evidence to show that it can meet even that minimal standard.

Morocco has thus failed to provide evidence that it can satisfy any of the required determinations.

Even Moroccan Law Provides Little Information on the Types of Material for which Import Restrictions Are Sought

There are three Moroccan cultural property laws available on U.S. databases, each of which amends but does not replace the prior laws. Different legal regimes apply to “listed” or “classified” and “unlisted” movable and immovable objects in all three laws. The types of objects the laws cover change or are re-defined over time and it is not always clear (with the exception of excavated objects) which antique and ancient objects fall in to the listed and unlisted categories and which are inalienable and imprescriptible.

- Law 1.80.341 of 17 Safar 1401 (December 25, 1980).

- Law No. 2.81.25 of 23 Hijra 1401 (October 22, 1981) issued for application of Law No. 22.80.a

- Amended in 2006 by Royal decree no. 1-06 102 of 18 Joumada 1427 (June 15, 2006)

In general, Morocco allows private ownership of both antiques and antiquities, although transfer of certain objects must be documented, and the state given the option to purchase it when transferred. Excavated archaeological materials are automatically deemed state-owned. In 2006, the definition of movable property was refined to include “documents, archives and manuscripts who archaeological, historic, scientific, aesthetic, or traditional aspects are of national or universal value.”

Movable and immovable property may be ‘listed’ or ‘classified’ and thereafter be subject to requirements for documentation and/or restrictions on transfer (1980), but “movable objects belonging to individuals are subject to registration or listing with the agreement of their owner.” (1981)

If the government does list a privately-owned object or monument then it has the right to step in to preserve the property. If an unlisted property is endangered, the government may order automatic listing. A classified movable item may not be restored, mutilated, modified, destroyed, altered or exported. But – the total or partial declassification of an immovable item or the declassification of a movable item may be requested by the administrative authorities or by individuals. There are rights of pre-emption by government and a right for the government to purchase with compensation in certain circumstances. These rights may also be waived by inaction. Owners of private museums must list their inventory. Museums, owners of collections, and individuals must allow access to their property for study. (2006)

Morocco has provided no explanation of how any items restricted under a U.S. MOU would correlate to these categories under Moroccan law. In general, it is the Committee for Cultural Property’s and Global Heritage Alliance’s position that no object that may be traded, transferred or sold legally in Morocco under its domestic laws should be illegal to import into the United States.

Conclusion

Mandatory statutory determinations must be based on evidence and facts, not speculation. Without having provided the facts substantiating the four determinations, Morocco does not meet the criteria required by the Cultural Property Implementation Act to justify an MOU. It hardly needs repeating that every one of the statutory criteria must be met in order for the U.S. to implement import restrictions under the Cultural Property Implementation Act.

Under the aegis of the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, import restrictions under the CPIA have provided for near permanent bans on the import of virtually all cultural items from the prehistoric to the present time from the countries which have sought agreements. If it fails to heed the concerns of Congress regarding overbroad import restrictions unsubstantiated by clear evidence of meeting the four determinations, CPAC would not only act in derogation of U.S. law, but also lend support to what Congress feared, an exclusively statist rather than internationalist policy on cultural heritage.

Caves of Hercules, Cape Spartel, Morocco, photo by Diego Delso, diego.delso, 11 December 2015, license CC BY-SA. Wikimedia Commons.

When the CPIA was passed, Congress never indicated that it was in the interests of the United States to block imports of all art and archaeological materials from source countries. Congress contemplated a continuing trade in ancient art except in objects at immediate risk of looting. Nor did Congress state that halting the trade in art was a positive goal. On the contrary, Congress viewed the CPIA as balancing the United States’ academic, museum, business, and public interests by assisting art source countries to preserve archaeological resources and ensuring the U.S.’s continuing access to international art and antiques through a relatively free flow of art from around the world to the United States.[11]

As both the Committee for Cultural Policy and the Global Heritage Alliance have stated in the past, and doubtless will have to state again, the Cultural Property Advisory Committee should live by the law that created it. It should apply a plain reading to the four determinations it must make.

CPAC can follow the dictates of Congress. It can honor and respect the limitations of the law by not signing Memoranda of Understanding with governments that fail to meet the statutory requirements of the CPIA. It can ensure, by demanding specific language that exempts the heritage of minority peoples who have been persecuted and exiled, that import restrictions are not imposed on community and personal property that has been seized, disrespected and despoiled. Import restrictions should only be imposed in situations where the facts and the law support them.

Once again, the Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance respectfully request that Morocco’s request for import restrictions be tabled, that the full text of the Morocco request be supplied to the public, and that the public be given a meaningful opportunity to address the range of materials sought to be restricted and the chronological scope of the request.

Kate Fitz Gibbon, Committee for Cultural Policy

[1] The Committee for Cultural Policy, POB 4881, Santa Fe, NM 87502. www.culturalpropertynews.org, info@culturalpropertynews.org.

[2] The Global Heritage Alliance. 1015 18lh Street. N.W. Suite 204, Washington, D.C. 20036. http://global-heritage.org/

[3] Letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo Regarding Cultural Property Agreements, Jimena, December 9, 2018, http://www.jimena.org/letter-to-secretary-of-state-mike-pompeo-regarding-cultural-property-agreements/

[4] The Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, 19 U.S.C. §§ 2601, et seq.

[5] The four determinations are found under 19 U.S.C. 2602(a)(1(A-D). According to the website of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, “public comments should focus on the four determinations.” https://eca.state.gov/highlight/cultural-property-advisory-committee-meeting-april-1-3. Last visited 2019/03/25.

[6] Federal Register: August 21, 2019 (Volume 84, Number 162 (Page 43462).

[7] James F. Fitzpatrick, Falling Short – the Failures in the Administration of the 1983 Cultural Property Law, 2 ABA Sec. Int’l L. 24, 24 (Panel: International Trade in Ancient Art and Archeological Objects Spring Meeting, New York City, Apr. 15, 2010).

[8] See Senate Report No. 564, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess. at 4 (1982)

[9] See Senate Report No. 564, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess. at 6 (1982)

[10] See What Can I do With My Ivory? https://www.fws.gov/international/travel-and-trade/ivory-ban-questions-and-answers.html

[11] 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(A-D) and 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(4)

Antique carpet shop, Morocco, photo by Safaa2606, 28 June 2018, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Antique carpet shop, Morocco, photo by Safaa2606, 28 June 2018, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.