The Montana Legislature’s State Administration Committee held hearings in March 2019 on a bill that would have made it a crime in Montana to buy, sell, exchange, distribute, market, or otherwise transfer a Native American ‘object of cultural patrimony’ or a ‘sacred object.’ The bill gave a burial board previously tasked with dealing with unmarked graves and other finds of human remains the job of responding to claims that items, including private property of collectors and inventory of businesses, were sacred or inalienable cultural patrimony, and adjudicating their ownership between the current owners and tribal claimants.

The bill, HB 637, was titled in full, “An Act Prohibiting The Sale or Other Commercial Transaction of Cultural Patrimony and Sacred Objects; Providing Requirements to Establish an Object as Cultural Patrimony or a Sacred Object; Providing a Penalty; Providing Definitions; and Amending Sections 22-3-802, 22-3-803, 22-3-804, and 22-3-808, MCA.”

The bill’s sponsor, Mr. Tyson Runningwolf, addressed the bill at a hearing on March 15, 2019. He described how the return of sacred artifacts such as medicine bundles, which provided a link to sacred knowledge, was necessary for his own tribe, the Blackfoot, in order to heal a fractured tribal society. He described a repatriation he had participated in the day before:

“We were lucky enough to get some money from different people to get some other items that are cultural patrimony and sacred items… off of the guys wall, and we brought them to a high school that is suffering from suicide – historical trauma. It’s never been done before, and people told us that we would never be able to walk into the school with these sacred and ceremonial items that were taken off the wall and we had to pay money for, but we made the sacrifice and we’ve done it. This school is in a healing process, and it is all due to these sacred items. We are bringing them back to the people, led by the children. It was historic.”[1]

Mr. Runningwolf did not present evidence during the hearing that there have been any recent violations of burial laws. Instead he read from a press release from the Association on American Indian Affairs, which described items in trade as often being taken in violation of federal, state and tribal laws.

The National Museum of the American Indian building in Washington is a remarkable structure that combines flowing curvy lines with a strong vertical fortress-like shape. The primary designer was the Métis and Blackfoot Indian architect Douglas Cardinal. 21 February 2010. Photo by O Palsson.

Committee member Frank Garner asked: Are there other states where this is the law?”

Mr. Runningwolf stated several times that there were parallel laws in other states, including Arizona, New Mexico, Oregon, and Nebraska. Mr. Runningwolf said “It is mirrored right through,” and “it is done in other states just like this.”

That prompted another committee member to ask: “I had an aunt that passed away and she lived in a state that you mentioned had these rules… Could she have been fined and put in prison?” He replied, “Only if she wasn’t consulting with the state or free-will giving it back to an organization or a tribe that wanted it back.”

(In fact, no U.S. state currently has a law such as HB 637, under which a state-appointed review board has the role proposed in the Montana bill. Human remains and certain cultural objects are repatriated from federally funded museum, university, and government collections under NAGPRA provisions. Some states have enacted state burial laws to deal with human remains and funerary objects found on private or state-owned land. An action by a state burial board to adjudicate ownership rights over legally-purchased private property, based on a tribal claim and without evidence of violation of law, would raise serious constitutional ‘takings’ of private property and due process issues.)

One member questioned information witness Mr. Mike Manion, chief legal counsel and deputy director for the Montana Department of Administration, whether the burial committee could take on the responsibility for administering the law. Mr. Manion answered that he had queried the burial board and nobody objected to assuming these responsibilities. However, he noted that the board’s total budget is about $11,200 for each fiscal year. He said, “If someone makes a claim for an object and a private person has it, the private person says well wait a minute, I bought this legally and I have a right to it, the board would have to in effect adjudicate that. When you get into a hearing, it could cost some money. We’ll make it work if that is your will, but we might have to come back and ask for money.”

Mr. Runningwolf stated at the closing of the hearing that he felt this was a preventive bill, and not one where “we would go out and say, ‘We got you!’” He stated that 85% of the time, when he personally has asked a private collector if they would simply give him the sacred object and allow him to “take it home,” they said, “Go ahead and take it off the wall if it is that important.”

Committee members had also heard from Montana’s small-business community, collectors, and historical societies about the problems that could result from HB 637’s lack of due process for owners and potential for overreach by Indian claimants, although none presented at this hearing.

Given the failure to define what was unlawful to buy, sell, or pass through inheritance, the ease with which an object could be claimed to be sacred or cultural patrimony, and the fact that there need not have been an unlawful transaction in the past, the public could be at constant risk of violating the law without knowing they could be breaking it if HB 637 passed. The bill was also criticized for inaccurately claiming that graves and grave goods were not already protected under Montana law. The bill failed to pass through the committee on April 25, 2019 and did not reach the Montana House.

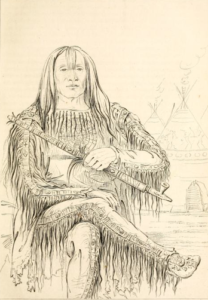

Original artwork of the head chief of the Blackfoot nation in the travel narrative Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians by George Catlin, 1842, Wikimedia Commons.

Nonetheless, the attempt to pass HB 637 provides an important example of how challenging it can be to return key objects to tribes, while at the same time preserving Constitutional protections and rights of due process to lawful holders of Native American art and artifacts.

The bill’s proponents apparently did not consider alternatives such a creating a grant system to enable tribes to purchase the truly important objects that occasionally come up for sale in legal trade, or to encourage current owners to donate them by means of tax incentives, or by devising another process for review that guaranteed transparency and required that there be due process protections for current lawful holders before forfeiting objects to tribes.

Instead, HB 637 could have made the trade and collecting of Indian art and artifacts a minefield for dealers, collectors, and museums, in which they could not take a step without potentially incurring severe fines or jail time simply by buying or selling items long in circulation that a tribal-majority burial committee held to be ‘sacred’ or ‘cultural patrimony.’

Parallels with proposed federal legislation

The argument that tribes should be given the ability to claim objects collected decades or more than a hundred years before, without specifically identifying which objects are covered, is a strategy familiar from the several unsuccessful attempts since 2016 to pass export legislation under the “Safeguard Tribal Objects of Patrimony Act of 2017” (STOP) and its 2016 predecessor. The STOP Acts called for essentially closed systems of tribal review, without the due process of law that American citizens expect.

Details of the Montana Bill

Definitions broader than NAGPRA – an undefined ‘ceremonial transfer’ provision

HB 637 defined sacred objects and cultural patrimony more broadly than the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), the primary federal legislation.

HB 637 Article (7)(a) stated that, “Sacred object” means a specific ceremonial object that is necessary to traditional Indian ceremonial leaders for the practice of traditional Indian ceremonies by their present-day adherents and requires a ceremonial transfer to be transferred from one person to another.

HB 637 Article (4) stated that, “Cultural patrimony” means an object: (a) that has ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to an Indian tribe, group, or culture itself; (b) that cannot be alienated, appropriated, or conveyed by an individual regardless of whether the individual is a member of the Indian tribe or group; (c) that was considered inalienable by the Indian tribe or group at the time the object was separated from the Indian tribe or group; and (d) for which the duties as a caretaker are transferred through a ceremonial transfer.”

These definition were similar to NAGPRA’s with the addition of the language about ceremonial transfers.

Burial review board with a permanent majority of Indian tribal members

The determination whether an object fit one of these categories and was therefore unlawful to buy or sell would be made by a burial board composed of at least eight Indian members and no more than five non-Indian members. It would include one representative of each of the seven Indian reservations, one person from the Little Shell band of Chippewa Indians, one person nominated by the Montana state historic preservation officer, one representative of the Montana archaeological association, one physical anthropologist, one representative of the Montana coroners association, and one member of the public.

How the board would define ‘cultural patrimony’ and ‘sacred’

Walter McClintock papers, 1874-1946. Karge, Annette. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Wikimedia Commons.

The board would have the ability to, “establish an object as an object of cultural patrimony or a sacred object,” without requiring outside expert review or possibility of appeal.

An object could be “established as an object of cultural patrimony” by evidence from:

“(1) an Indian tribe or group that can show that the object of cultural patrimony was owned or controlled by the tribe or group;

(2) a direct lineal descendant of an individual who owned the sacred object;

(3) an Indian tribe or group that can show that the sacred object was owned or controlled by a member of that tribe or group; or

(4) an Indian tribe or group that can show that the object of cultural patrimony or the sacred object was transferred through a ceremonial transfer.”

The reviewing burial board would set up a process to evaluate and establish an object as an object of cultural patrimony or a sacred object including verification of the evidence presented regarding the object’s history and nature; store an object under review while the board establishes the object’s history and nature, determine if the object will be returned to an Indian tribe or group, determine the method to return an object that has been designated for return to an Indian tribe or group; and provide a process to accept and return an object of cultural patrimony or a sacred object from someone who voluntarily turns over an object to be returned to an Indian tribe or group.

HB 637 also permitted any related Indian tribe which alleged that there was group ownership of an item, or any lineal descendant of an individual who had owned the object at a previous time, to claim it as cultural patrimony or a sacred object, even if the object has been legally owned and transferred in the past, by showing that the object was transferred through a ceremony.

Opponents to the bill felt that the reviewing system in the bill left too great uncertainty in defining what was unlawful to trade, and a failure of due process in the review board’s ability to unilaterally define an object as cultural patrimony or sacred.

Penalties

Tipi by the Blackfeet (Pikuni) Nation, shown in the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, D.C. August 2007, Photo by Gryffindor. Wikimedia Commons.

The penalties for buying or selling Native American artifacts included in the categories of cultural patrimony or sacred objects included both large fines and imprisonment. A person convicted of buying or selling an ‘object of cultural patrimony’ or a’ sacred object’ could be fined $10,000 and imprisoned for six months.

Disturbing a burial had more severe penalties of imprisonment for six months and $1,000 fine for disturbing or pilfering from an unmarked grave, and twenty years imprisonment and a $50,000 fine for knowingly engaging in a commercial transaction with human remains or items found in a burial for a first offense.

Graves and grave goods already protected under Montana law

The proposed law also contained extensive provisions regarding protections for graves and grave goods. However, there is existing Montana law dating to 1991, the Human Skeletal Remains and Burial Site Protection Act, that sets forth procedures for protecting all human remains, burial sites, and burial materials in marked or unmarked graves or burial sites located on state or private lands. The 1991 law addressed what must be done after the discovery of any human remains, regardless of ethnic origin, burial context, or age. (It is noteworthy that a key omission from this 1991 law which would have provided for repatriation of human remains discovered prior to 1991 was not explicitly addressed in HB 637 either.)

A legal analysis of the 1991 Montana law in August 2000 by the Montana Legislative Services Division states that contrary to popular belief, goods found in Indian graves do not belong to the finder under Montana law. “[W]henever funerary objects are removed from graves, they belong to the person who prepared the grave or to the known descendants of the deceased.”[2]

The 1991 law, therefore, disposed of some of the concerns about misappropriation of sacred objects that the 2019 law was intended to address. The substance of the 2019 HB 637, and its true impact, lay in granting a permanent Indian-majority review board with powers to characterize legally-owned objects already in circulation in trade or held as part of private or museum collections as sacred objects or cultural patrimony, and to direct them to tribes, apparently without requiring an evidentiary standard or due process of law.

[1] Audio recording of meeting of State Administration Committee, Hearing, Friday, Mar 15, 2019, 08:00 – 10:35, available at http://sg001-harmony.sliq.net/00309/Harmony/en/PowerBrowser/PowerBrowserV2/20170221/-1/34985?agendaId=137187

[2] Montana’s Human Skeletal Remains And Burial Site Protection Act: Repatriation And Board Reimbursement, Prepared by Eddye McClure, Staff Attorney, Legislative Services Division, August 2000, p 3. https://leg.mt.gov/content/Publications/Legal-Opinions/0801000213EMIALGL.pdf

Blackfeet Indian Reservation looking at the mountains of Glacier National Park. Rmhermen at the English language Wikipedia.

Blackfeet Indian Reservation looking at the mountains of Glacier National Park. Rmhermen at the English language Wikipedia.