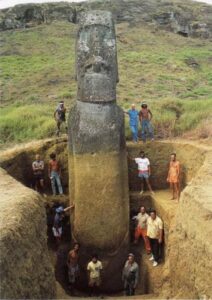

Excavations by Dr. Jo Anne Van Tilburg and her team at Rano Raraku quarry on Rapa Nui. Photo credit: Easter Island Statue Project. Courtesy of Forbes/UCLA.

Moai, the monolithic stone figures representing ancestors and powerful chieftains, are synonymous with Rapa Nui, as Easter Island is now known. The giant moai were carved between A.D. 1100 and 1500; their likely purpose was to commemorate the death of an important tribal leader. Rapa Nui has been completely closed to tourists during the Covid pandemic. It was reopened only on August 5 of 2022.

Rapa Nui authorities reported that a number of moai were severely damaged in a human-set fire that raced through 100 hectares (247 acres) of the Rapa Nui national park on October 6. Only a few photographs of burned moai are available and details on the number of charred heads in the burned areas around the Raro Rarako volcano are unknown. Several hundred Moai are located in the Raro Rarako area; the quarry on the outer side of the volcano where stone for carving moai was extracted may also have been affected. According to Rapa Nui officials, a “lack of volunteers” caused delays in putting out the fire.

Easter Island mayor Edmunds Paoa told the press that, “The damage caused by the fire can’t be undone. The cracking of an original and emblematic stone cannot be recovered, no matter how many millions of euros or dollars are put into it.”

A Moai statue whose right earlobe was stolen by a Finnish tourist. Chilean Investigative Police photo.

The moai are highly protected under Chilean law – and by their importance to the island community. It is illegal to touch any of the nearly 1000 moai on the island. A Finnish tourist caused a “national uproar” and was fined $17,000 for chipping part of an earlobe off a moai in 2008. In 2020, a Chilean resident on the island failed to properly brake his pickup truck, which rolled down a hill empty, striking and completely destroying a moai and its plinth at the bottom. Many more moai have been lost to natural erosion of cliffs and damage from high seas and rough weather. Many people of Rapa Nui, although the spiritual traditions that produced the moai are long past, are nonetheless committed to preserving and honoring their cultural history.

Archaeological work has been going on at the inner quarry area of the volcano since 2002, led by Dr. Jo Ann Van Tilburg in collaboration with all-Rapa Nui community archaeologists and staff.

A truck that has crashed into and destroyed a moai. Comunidad Indígena Ma’u Henua.

Excavations have revealed massive torsos with elaborate carving beneath the ground that are far better preserved that the exposed heads. Dr. Van Tilburg’s team has also identified and mapped thousands of habitation sites on the island. Their work also includes the study of numerous small portable objects that were a form of personal art honoring ancestral spirits in wood and stone, locating them with the help of researchers in museum and institutional collections worldwide.

Dr. Van Tilburg has described the communal making of the monumental moai as a form of public commemorative monuments. With other researchers into Rapa Nui culture, she has helped to develop a program of “community archaeological and heritage preservation.”

Two Moai are shown during excavations by Jo Anne Van Tilburg and her team at Rano Raraku quarry on Rapa Nui, better known as Easter Island. Photo credit: Easter Island Statue Project.

There are over 900 moai located on Rapa Nui. They lie scattered in fields on hilly slopes, and along the island’s sea border. Many are half buried, by tradition or because many standing moai had fallen or been pushed down by the 18th and 19th century. The statues (often erroneously called “heads” because of their disproportionate size and the fact that many were buried to the shoulders) stand 13 feet high on average; the largest, called Paro, was 33 feet tall and weighed over 90 tons.

By the time it was known outside of Easter Island, the moai tradition had faltered, in part as a result of European contact and the rise of another religious cult of Tangata Manu, or Birdman. Recently, indigenous pride, recognition of the moai’s importance to the island’s history, and the rise of tourism, have resulted in many moai being raised again, including those originally placed on stone platforms called ahu. These characteristically face inland, away from the sea.

Front of the Moai at the British Museum, By Szilas, via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the most famous moai has been in the British Museum since 1868, when it was donated by Queen Victoria. Rapa Nui officials have asked the British government to return the iconic stone moai statue called Hoa Hakananai’a. In response to the British Museum’s declining to return the statue, one of the museum’s best known artifacts, the Easter Islanders are now proposing that they carve a replica of Hoa Hakananai’a and trade it for the original.

This sculpture has a unique history described in a Cultural Property News article in 2018:

“The moai in the British Museum, the Hoa Hakananai’a, was created around 300 or 400 years ago during a transitional time in the cultural narrative of the people of Rapa Nui. In this period the moai tradition, involving the creation of giant statues imbued with the ‘mana’ life force of the ancestors, was superseded by another spiritual tradition known as Tangata Manu or Birdman.

The Birdman tradition involved a yearly ritual contest involving the retrieval of the first sooty tern egg from a nearby islet, which decided who should hold tribal authority for the year. There are multiple layers of carvings on Hoa Hakananai’a’s back that suggest its repurposing during this transition. Researchers say the more recently carved images are symbolism from the Birdman tradition, the older ones from the ancestor mana tradition.

Back of the Moai, by BabelStone, via Wikimedia Commons.

Theories of the evolution from the moai to the Birdman tradition on Rapa Nui have been pieced together using the journals of sailors who visited the island and the remaining oral history that survived the decimation of the Rapa Nui people in the 18th century, first by Peruvian slavers and then by the smallpox. Some material evidence of the transition has also been gleaned from examination of the images on moai and other stone carvings.

Even prior to European contact with the island’s people in 1722, the Moai tradition was in a period of decline, possibly due to social upheaval resulting from deforestation and environmental degradation. In 1724, a period of intertribal warfare commenced that continued until the 1860s. The arrival of Peruvian slavers in 1862 virtually stilled Rapa Nui cultural life. The slavers captured about 2000 Rapa Nui, including the priests and chiefs who held much of the cultural knowledge. An estimated 90% of the captured Rapa Nui died in Peru.

Peru attempted to return the remaining enslaved Rapa Nui three years after their capture, but many died of smallpox en route to their home. The few that survived the journey transmitted the infection to the estimated 1,500 inhabitants still remaining on the island. By 1877 only 111 Rapa Nui had survived both the smallpox, a tuberculosis outbreak and then a forced relocation to other islands. Much of Rapa Nui’s cultural knowledge was gone with the death of its leaders and elders.

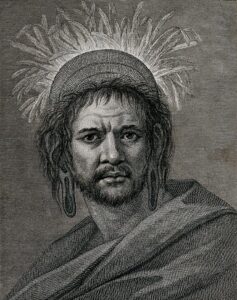

A man from Rapa Nui with elongated ears, encountered by Captain Cook on his second voyage, 1772-1775. Engraving by F. Bartolozzi, 1777, after W. Hodges. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain.

The controversy over the Hoa Hakananai’a in the British Museum raises important questions regarding the benefits of retaining objects in foreign museums in order to share the richness and variety of global cultural heritage with a broader audience. Certainly, not everyone can visit the British Museum, but the Hoa Hakananai’a is seen by about 6 million visitors a year there, as one of its most popular exhibits. Far fewer visitors will ever be able to see Rapa Nui’s cultural heritage on Easter Island, and the people who do travel to Easter Island will be able to see the Hoa Hakananai’a’s 900 giant stone kin in their traditional cultural environment.

The Rapa Nui, on the other hand, point to the Hoa Hakananai’a’s significance as an ancestor of the people, and endowed with a life force called mana. They have said that moai provide protection and the presence of this particular moai on the island may help restore its ecology and the Rapa Nui’s culture. With recent improvements to their heritage conservation infrastructure, the Rapa Nui state that they are well able to bring Hoa Hakananai’a home and to care for it.

It is not known when Hoa Hakananai’a lost its significance to the Rapa Nui people as part of the Birdman or other cultural tradition. It is known that the Hoa Hakananai’a was found on 4 November 1868 by Lt William Metcalf Lang and Dr Charles Bailey Greenfield of H.M.S. Topaze on Easter Island. The stone giant was buried up to its shoulders inside a ceremonial stone hut at Orongo, at the Rano Kau volcano, which was the center of the Birdman tradition. At the time, its torso was decorated with patterns in red and white.

William Hodges, A View of the Monuments of Easter Island (depicting moai) , Rapanui, 1795, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England.

According to early sources, Hoa Hakananai’a was gifted to the English seamen by the island chiefs, who were newly converted to Christianity. The Rapa Nui peoples are described as helping to take the moai to the ship in several sources, the most intriguing being on a tattoo that was recorded in 1884, showing Hoa Hakananai’a positioned perpendicular to a rope, being dragged overland to H.M.S. Topaze.

Lt. Colin M. Dundas witnessed and recorded this procedure:

‘We sent a party of 40 men to disinter this image, and having got him out a large party were sent to drag him to the ship, a distance of more than three miles wc. [which] they accomplished by making a sledge of capstan bars & dragging him broadside on over the softer ground & end on up the steep places.’

Horses on Rapa Nui with moai behind them, by maryatexitzero , via Wikimedia Commons.

Dr. Jo Anne Van Tilburg noted in Lost and Found: Hoa Hakananai’a and the Orongo “Doorpost,” that after an “impromptu Rapanui ceremony… nearly all members of what was then a small Rapanui community—collected Hoa Hakananai‘a from the ceremonial village of Orongo,“and helped to transport the figure to the ship “as a trade commodity.” Hoa Hakananai’a is also described in some sources as a gift to Queen Victoria, and it was she who presented the stone statue to the British Museum.”

Six of the 15 Ahu Tongariki Moais, photo by Rivi, 29 March 2006, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

Six of the 15 Ahu Tongariki Moais, photo by Rivi, 29 March 2006, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.