“Over 18,000 items seized and 59 arrests made in operation targeting cultural goods,” a July 29, 2019 Europol press release

“… in September 2017, a car coming from the Netherlands via Bulgaria… was considered “high risk” and thereby deserving of a physical search that led to the seizure of 2,400 of long-play records. According to the expert’s report for this case, these records were considered protected within the scope of national legislation.”

From the World Customs Organization 2017 Illicit Trade Report, “Successful cooperation between Customs and culture experts in Turkey,” p. 18.

Old news mixed into the headlines… again

Reports and press releases citing two and three-year old seizures of “cultural objects,” are hitting the media – well-timed to counter the lack of evidence of illicit trade found by the ILLICID Report. A reprise of two earlier customs and police campaigns, Pandora III, was recently announced, along with high seizure numbers and little details about what the numbers represent.

ILLICID, a two year, highly promoted $1.2 million euro project funded by the German government, found none of the evidence its director promised for significant numbers of illicit objects being traded internationally, and none whatsoever of terrorist involvement in the art trade. Perhaps this was shocking to anti-trade activists but it came as no surprise to the art world. (See Was Illicid Report Buried for Failing to Show Illegal Trade?, Cultural Property News, July 14, 2019.)

An over-blown 2016 Pandora

Europol press release image of seized items. Europol.

Pandora II was a two-month, nineteen-country marathon search and seizure effort that sought to capture antiquities coming into Europe from North Africa and the Middle East. It reaped not a single object of importance (though it did retrieve coins stolen by thieves from a Spanish museum). The most recent effort, Pandora III, now claims to have located Greek and Roman coins, a 15th-century Bible, and a Mesopotamian crystal cylinder seal. Not much to report out of 18,000 items seized.

In the main, the objects seized during Pandora I and II were of very low to nil value. The seized items included such ‘treasures’ as hundreds of rusty WW2 cartridge casings and fragments of weapons taken from an elderly Polish man who failed to get a license from City Hall for his otherwise legally-permitted metal detectoring.

Pandora II involved searches of more than 48,000 individuals, 29,000 vehicles, and 50 vessels. Customs officers and police found hundreds of heavily encrusted coins, a wide variety of ceramic shards, a common early Islamic period ring (value about $20), a foot-long fragment of a marble Ottoman tombstone, and a mediocre eighteenth century painting of St. George.

Authorities were looking for items coming from war zones, but they were not mentioned in any police reports. The paltry results from Operation Pandora II produced no evidence for a European trade in antiquities from the Middle East. (See Pandora’s Big Disappointment, Cultural Property News, January 30, 2017.) While the full reports aren’t yet in, the preliminary data suggests a repeat of the same patterns, inter-European trade, objects from the CIS, and a dearth of evidence of trade in looted monuments and antiquities from areas of conflict.

What is a “cultural object” for the purpose of documenting illicit trade?

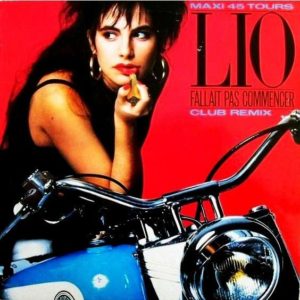

Lio’s 1986 Fallait pas commencer.

Europol is not alone in promoting the idea that there is massive trade in illicit “cultural objects.” Organizations from UNESCO to the EU Parliament use this expression to cover a world of miscellaneous objects, most of them of no market value. It is common to see expressions such as ‘treasures’ and ‘irreplaceable cultural heritage’ applied to utter junk, so long as it is old junk. The ancient objects seized in 2017 that are depicted in the World Customs Organization report are not hacked from monuments or even likely to have been dug from archaeological sites but are rather the sorts of objects that have sat in bazaars by the thousands for decades. From all these factors, substantial confusion and misunderstanding of the scope and volume of illicit trade in ‘cultural goods’ results.

What is a “cultural object” or “cultural good” for the purpose of the World Customs Organization, Interpol, and Europol? Is it correct to transpose this general term into ‘treasure,‘ and for politicians and activists to treat ‘cultural goods‘ as equivalent to ‘inalienable objects of cultural heritage‘? Yet this term is used by law enforcement to cover everything handmade or to do with human culture.

The vast majority of objects described in statistics in ‘cultural property crime’ are simply handmade goods of any kind and of any age, such as the furniture, carpets or silver stolen from people’s homes that comprises most ‘cultural property crime.’ Like the low-value coins used to illustrate Europol’s histrionic press release, seizures of cultural objects can be relatively recent, common objects… even vinyl records.

World Customs Organization Illicit Trade Reports and WCO Customs Enforcement Network

The World Customs Organization’s annual illicit trade report covers a variety of subjects each year, picking out highlights of activities from participating customs agencies from around the world. The report utilizes information drawn from a global database of Customs seizures in six major areas of enforcement. The “cornerstone… for the analysis” is the “WCO Customs Enforcement Network (CEN), a global database of Customs seizures in six major areas of enforcement.”

The categories covered in the annual report are cultural heritage; drugs; wildlife and environment; IPR (counterfeit non-medical goods, including clothing and accessories, cosmetics electronic appliances) and medical goods (including pharmaceuticals and smuggled medical technology); revenue and security (counterterrorism, weapons, etc). Each year, more countries contribute to the report; in 2017, 133 countries submitted data. Yet the reader perusing this major report might be surprised by what authorities consider ‘cultural heritage.’

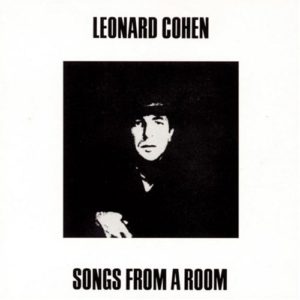

Leonard Cohen, anyone?

“In April 2017, at the Edirne, Kapıkule border crossing point, a truck coming from France via Bulgaria, was subject to a routine control by Customs officers. During the cabin search of the truck, officers seized 250 pieces of 45-rpm and 260 pieces of 33-rpm phonograph records. Then, in September 2017, a car coming from the Netherlands via Bulgaria, through the same border crossing point, was considered “high risk” and thereby deserving of a physical search that led to the seizure of 2,400 of long-play records. According to the expert’s report for this case, these records were considered protected within the scope of national legislation. These two cases comprise the largest seizures executed by Turkish Customs units in 2017.”

“In April 2017, at the Edirne, Kapıkule border crossing point, a truck coming from France via Bulgaria, was subject to a routine control by Customs officers. During the cabin search of the truck, officers seized 250 pieces of 45-rpm and 260 pieces of 33-rpm phonograph records. Then, in September 2017, a car coming from the Netherlands via Bulgaria, through the same border crossing point, was considered “high risk” and thereby deserving of a physical search that led to the seizure of 2,400 of long-play records. According to the expert’s report for this case, these records were considered protected within the scope of national legislation. These two cases comprise the largest seizures executed by Turkish Customs units in 2017.”

The photograph is fuzzy, but sitting atop these seized records are Leonard Cohen’s 1969 album Songs from A Room (Internet price about $20), French singer Lio’s Fallait pas commencer (49 cents to 6.00€), and even some recordings of Chopin. These were the largest seizures of cultural goods made by Turkish Customs units in 2017. And according to the World Customs Organization, the LPs and 45s were considered protected cultural heritage within the scope of Turkish national legislation.

World Customs Organization 2017 Illicit Trade Report – a wealth of information

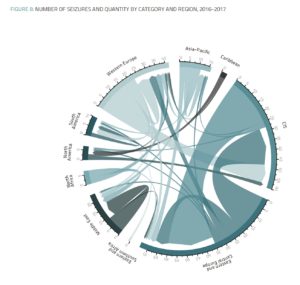

The World Customs Organization 2017 Illicit Trade Report, published in September 2018, is in some respects a scattershot approach to reporting on seizures, but it also has many helpful graphs, summaries and graphics that reflect the input of the contributing counties. These analyses depict the movement of illicit objects from one country to another. Contrary to widespread press reports about millions or even billions of dollars-worth of antiquities coming from war-torn regions into the legitimate art market in Europe or the US, the report shows trafficking in all cultural goods from the Mideast going almost exclusively to other Mideast destinations, not to Europe or the U.S.

According to the World Customs Report, in 2017, 25 countries submitted a total of 140 cases comprised of 167 individual seizures involving cultural objects. Customs officers identified 14,754 artefacts, including antiquities, paintings, statues. An increase in the number of seizures was thought to result from an increasing focus on cultural heritage crimes, “rather than a genuine uptick in cultural heritage trafficking.” (pg 8)

The types of goods seized included ethnological objects, musical instruments, religious items, engravings, prints, lithographs, and photographs, as well as antiquities. In the field of antiquities, which included “inscriptions, coins and seals,” there were 60 seizures, numbering a little over 7,500 objects in both of 2016 and 2017.

There were also:

- Archives of sound, film and photographs (four seizures and 3,169 pieces)

- household items including samovars and carpets (13 seizures and 1,056 pieces)

- archeological excavations (nine seizures and 716 pieces)

- 47 books and manuscripts

- 148 pieces of jewelry

- 39 statues and sculptures

- 50 antique weapons

(all p 10)

No values were provided for the items seized. The only high value items mentioned in the cultural goods section, at over one million dollars, had been illegally exported in 1981.

FIGURE 8: NUMBER OF SEIZURES AND QUANTITY BY CATEGORY AND REGION, 2016–2017, World Customs Organization Report 2017, p. 21.

By far the largest number of cases, outstripping all other countries by at least 5 to 1, were from the Russian Federation and the Ukraine. (The report also highlighted archaeological items and coins from the arrest of a gang of thieves in Spain who scoured archaeological sites with metal detectors.)

Readers will find it interesting to compare this data to the records for drugs: 105 reporting countries reported a total of 40,236 drug trafficking cases in 2017, involving 43,144 individual seizures of contraband narcotics.” A single, very large seizure of cannabis was valued at 9 billion USD. (p.46) Shipments of lesser known contraband, such as luxury goods, counterfeit semi-conductors, and even fake cigarettes described in the same report are frequently valued in the millions of dollars each.

Cultural Property News does not make light of crime, whether it is smuggling weapons, trafficking drugs, robbing archaeological sites or stealing from museums. But thoughtful, fact-based policies on cultural heritage are key to the intellectual, political and economic development of all nations. If instead of facts, policies are to be based upon rumors, exaggeration, and the sleight-of-hand manipulation of one term to stand for another – they will do harm, not good.

This article was updated July 31, 2019 to include additional information.

The largest single seizure of "cultural goods" in Turkey in 2017. This illustration appears on page 18 of the World Customs Organization 2017 Illicit Trade Report, “Successful cooperation between Customs and culture experts in Turkey,” p. 18, World Customs Organization 2017 Illicit Trade Report.

The largest single seizure of "cultural goods" in Turkey in 2017. This illustration appears on page 18 of the World Customs Organization 2017 Illicit Trade Report, “Successful cooperation between Customs and culture experts in Turkey,” p. 18, World Customs Organization 2017 Illicit Trade Report.