Requests for cultural property agreements blocking entry of art and antiquities from Lebanon, Mongolia, and El Salvador will come before the Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) at the U.S. State Department this September 24-26, 2024.[1] Written public comments on these requests must be submitted by September 16 to https://www.regulations.gov/commenton/DOS-2024-0028-0001.[2] Applications to speak briefly at CPAC’s 1-hour public hearing on September 24, 2024, at 2:00 p.m. (EDT) using Zoom must be emailed to culprop@state.gov by September 16, 2024.[3]

The U.S. appears ready to enter another cultural agreement with a broken government that has done little to protect its heritage – an excessively broad agreement that also fails to meet U.S. legal criteria. Lebanon’s request for import restrictions includes virtually any object ever created within its territory, in any medium, from any civilization, ethnic, or religious community, from the Paleolithic to the present.

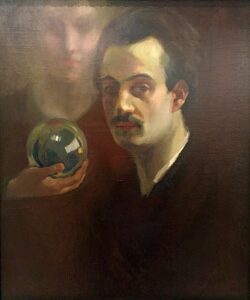

(The excessive breadth of Lebanon’s request for import restrictions reaches the point of absurdity: it claims as national cultural heritage even the works of Lebanese-American writer and poet, Gibran Khalil Gibran. Khalil Gibran, the author of The Prophet, moved with his mother to the United States in 1895 at age 12, and except for his return for 3 years of study in a Maronite school as a teenager in Lebanon, lived in the U.S. until his death. He was, in fact, an American.)

Ancient columns lie in the submerged Egyptian harbour of Tyre/Sour, South Lebanon, with the skyline of the modern city in the background, Roman Deckert, CCA-SA 4.0, November 4, 2019

The State Department has encouraged the Lebanese government’s request, despite its failure to provide evidence that each item listed as Lebanese heritage is currently subject to predatory looting and should be prohibited entry into the U.S. The list includes ancient glass and ceramic objects and ethnographic household objects and personal possessions, including costume, jewelry and coins – all described as in “daily use.” These hardly meet the definition of the “significant” objects covered in the statute. They also include the personal and religious possessions of Jewish and other minorities driven from Lebanon.

Lebanon avers that its own government has made sincere efforts protect these objects of cultural heritage from destruction and to halt their export, and that the U.S. is a primary destination for Lebanese looted items. However, as will be seen below, Lebanon’s government is not protecting its heritage and there is scanty, if any, evidence that there is current looting of objects in Lebanon that are subsequently marketed in the U.S. or anywhere else.

More than anything, Lebanon’s request – compared to its actual actions – shows the U.S. State Department’s disregard for the terms set by Congress for the legal protection of global heritage, and emphasizes how far its Cultural Heritage Bureau and the CPAC have strayed from the goals of the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act.

Lebanese history and background

Lebanon has long been a crossroads of trade and conflict, and no period has held greater strife than the last 75 years. Its rich historical legacy and significance in ancient times as an international entrepot and cultural center starkly contrasts with the ravaged and deeply fragmented nation that is Lebanon today.

In the early stages of human development, stone tool and weapon-wielding Neanderthals competed with Upper Paleolithic humans in the region, leaving behind aerodynamic stone and bone points. There are many true Stone Age settlements in Lebanon and evidence that the country formed part of the migration pathways of humans to Europe.

There is little doubt that these most ancient sites are at risk – but not by artifact seekers. Today, many of Lebanon’s prehistoric and ancient sites have been destroyed by government sanctioned development and even converted into cement quarries, erasing crucial parts of human history.

Anjar, Lebanon, Tetrapylon, UNESCO World Heritage Site. A fortified city surrounded by walls and forty towers. Vyacheslav Argenberg, CCA 4.0, September 17, 2008

Lebanon’s inhabitants seem to have taken some of the earliest steps in formal trade as early as the Bronze Age. The world’s oldest known scale beam, dating to the early third millennium BCE and probably used to measure grain or another foodstuff was found near Kfaraabida in North Lebanon, indicating that its inhabitants utilized advanced concepts of trade.[4]

From the middle of the second millennium BCE, the ancient Phoenician cities were hubs for Mediterranean trade. By the mid-first millennium BCE, ancient master mariners filled trading galleys with cedar and pine wood, fine linen, cloth dyed with Tyrian purple, embroideries, metalwork, glass, glazed faience, wine, salt, and dried fish oil, and sent Lebanese wares to ports around the Mediterranean.

Naturally, these riches drew conquerors bent on capitalizing on this trade; from Minoan times onward the Greeks both competed financially and fought with the Phoenicians. The Persians captured Lebanon under Cyrus the Great, and in the Roman period Beirut (Berytus) was a splendid metropolis. Among other wonders, it boasted the first school of Roman law in the eastern Roman Empire – founded by Septimus Severus in 200 CE.

Lebanese villagers during the era of Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate. Unknown author, Public domain, Late 19th, early 20th century.

During the early Byzantine Era, the region became a major center for Christianity. After the 7th century, however, it came under the political control of various Islamic caliphates, starting with the Rashidun Caliphate, followed by the Umayyads, and then the Abbasids. In the 11th century, the Crusades began, leading to the establishment of Crusader states.

These Crusader states were eventually overtaken by the Muslim Ayyubid Dynasty, then the Mamluk Sultanate, and finally the Ottoman Empire. During the Ottoman period, in the 19th century, Sultan Abdulmejid I established the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate. This Mutasarrifate was created as a semi-autonomous region for Maronite Christians during the Tanzimat reform period. After World War I, France acquired a mandate over part of the former Ottoman Empire, creating the state of Lebanon in 1920.

Following World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the region that is now modern-day Lebanon fell under the French Mandate for Syria and Lebanon. Under French administration, Greater Lebanon was established. During World War II, French authority in the region weakened significantly after the German invasion of France in 1940. By 1943, Lebanon gained independence from Free France.

Lebanon established a unique ‘confessionalist,’ religiously organized government system, which distributed political power among the major religious groups. The newly independent Lebanese state experienced a brief period of relative stability.

A group of Lebanese Arab Army soldiers during the civil war, between 1976 and 1983. Image from researcher Roy Arbaji’s archives. Posted by Haya Ma’amari, CCA-SA 4.0, CCA-SA 4.0 International.

The Lebanese Civil War that raged between 1975 and 1990 seriously destabilized the country. The chaos was compounded by a Syrian military occupation from 1976-2005, a large influx of Syrian refugees post-2011, and the rise of Hezbollah. A number of archaeological sites, including World Heritage sites, were damaged as a result of Israeli aerial bombardments in Lebanon, the most serious at Byblos.[5]

The UN reported in September 2006:

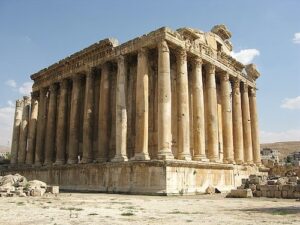

“Experts … found that major components of Lebanon’s cultural heritage had been spared by the recent conflict… The most serious damage resulting from the conflict concerns the World Heritage site of Byblos, which was affected by the oil spill from the fuel tanks of the Jiyeh power plant… The main features of the World Heritage site of Tyre, the Roman hippodrome and triumphal arch, did not sustain any damage… But frescoes in a Roman tomb on the site had come partly unstuck, probably because of vibrations caused by bombs, and required emergency restoration. The site of Baalbek, inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, was not damaged by bombs except for the fall of one block of stone… Fissures on the lintels of the temples of Jupiter and Bacchus at the site had probably widened because of vibrations from bombings nearby and warranted close monitoring…South of Baalbek, the World Heritage site of Anjar with its Umayyad vestiges was found to have been undamaged but is in a poor state of conservation.”[6]

The chaos that characterizes Lebanon today is the culmination of decades of turmoil resulting from political strife between Maronite, Catholic and Orthodox Christians, and Shia and Sunni Muslims – alternating with periods of prosperity and relative stability realized through collaboration between the key religious groupings, which also included substantial Druze and Jewish communities. Its ‘confessionalist’ government however, is faulted for its constant striving to protect each faction. The resultant dysfunction and corruption created Lebanon’s financial crisis and government negligence caused the 2020 port explosion that has devastated Beirut.

It is ironic that given its ancient contributions to foundational legal principles, modern Lebanon appears helpless in its current struggle for political stability and justice. Regrettably, the argument for the need to preserve and honor Lebanon’s historical and archaeological heritage is lost on both of its current and factionalized rulers, the fragile Lebanese Republic government and Iran-backed Hezbollah.

Sarcophagus known as the Tomb of Hiram I (c. 1.000 – 947 B.C.), Phoenician King of Tyre, but dated to the Persian period (6th century B.C.). On the road between Ain Baal and Qana, framed by Hezbollah flags. Roman Deckert, CCA-SA 4.0, August 12, 2019

The destruction of sites in regions controlled by Hezbollah shows that this terrorist organization places no particular value on preservation of ancient heritage. Regrettably, the corrupt officials of the Beirut government have also blatantly disregarded preservation, in their case, for the immediate rewards of dishonest development programs.

With regard to the trade in antiquities, Lebanon has been a center for trade in artifacts from its own sites and those of neighboring countries throughout the twentieth century. Despite the expertise and business skills for which Lebanese traders were famous, the quasi-legal, quasi-regulated trade in more modest antiquities declined along with all other commerce in the last quarter of the 20th century, as the country became embroiled in increasingly aggressive regional conflicts, with Israel, the Palestinians, Syria, and Iran either directly or through surrogates. In a few well-known instances (see below), there was opportunistic looting by militias of warehoused archaeological material, some of which was documented, enabling its later identification and return. The decade long civil war led to the antiquities being sold by all sides to fund militias and support powerful government officials.

Today’s Lebanese government officials (and today’s terrorists) have far more lucrative opportunities for enriching themselves than trading in antiquities: controlling basic foodstuff and energy, inflationary banking schemes, draining foreign funds from development programs, and general corruption and granting of favors.

Lebanon has become, for all intents and purposes, a failed state since the onset of the financial crisis in late 2019. The financial crisis was the result of a Ponzi scheme operated for years by the Central Bank, the commercial banks and the political establishment. Lebanon’s currency collapsed, inflation skyrocketed, and the country’s GDP plummeted. Many Lebanese lost the value of their life savings, worsening their economic situation. According to the Department of State, as of April 2024, Lebanon’s banks are insolvent, having accumulated more than $72 billion in losses.

(See: Lebanon’s Ponzi Financial Scheme has Caused Unprecedented Social and Economic Pain to the Lebanese People, World Bank Group, August 3, 2022.)

While Beirut is currently doing far better than the rest of the country, in the neglected Akkar region, for example, poverty surged from 22% to 62%. Stark disparities also exist between Lebanese citizens and Syrian refugees, with 33% of Lebanese living in poverty in 2022 compared to 87% of Syrians. Access to essential services such as electricity and education has disappeared for many. The Lebanese government brought this crisis on itself. International observers and the vast majority of Lebanese people agree that their government is irretrievably corrupt and will collapse without sweeping structural change. Lebanon needs other kinds of help from the U.S. and the international community than a cultural property agreement that will have no positive effect on its current crises.

Beirut’s heritage today. Building skyscrapers on Roman ruins.

Screenshot. On 4 August 2020, a large amount of ammonium nitrate stored at the Port of Beirut in the capital city of Lebanon exploded.

Throughout this disastrous modern history, Lebanon’s cultural heritage suffered substantial damage. Since October 2023, the levels of conflict and concomitant destruction have escalated following attacks by Hamas on Israel and subsequent Israeli retaliation on Hezbollah in Lebanon. Hezbollah’s ongoing conflict with Israel and other groups continues to pose serious risks to cultural sites.

However, the Lebanese government has been responsible not only for the greatest damage to heritage but also for inestimable human suffering. The 2020 Beirut Port explosion was an avoidable consequence of callous government indifference to public safety. A 127-page report issued by Human Rights Watch in 2021 implicates the highest level officials in the government (who have since taken steps to immunize themselves from prosecution, including by removing judges). The report makes clear that the port explosion, one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history, was the result of “longstanding corruption and mismanagement at the port, that allowed for tonnes of ammonium nitrate, a potentially explosive chemical compound, to be haphazardly and unsafely stored there for nearly six years.” [7] According to HRW, In the days following the blast the weeping prime minister confessed that the blast was the result of endemic political corruption and that the “system of corruption is bigger than the state.”[8]

Memorial for those lost in the port explosion, Photo Behnam Tofighi, Mehr News Agency, 5 August 2020, CCA 4.0 International License.

The blast killed 218 people and wounded 7,000. It displaced some 300,000 people including 80,000 children left homeless. It has left 800,000 tons of construction and demolition waste, much of it loaded with toxic chemicals that covered a large section of the city.

Crucially for heritage concerns, the explosion caused enormous damage to the most historic sections of Beirut from its time as a Roman port. Of the reported 8,000 structures damaged in the explosion, 640 had heritage status, according to UNESCO. Restoration of damaged museums in the area has largely depended on foreign aid.[9]

Corrupt development is the chief barrier to archaeological work and preservation activities

The port explosion also exposed the deliberately hidden erasure of important archaeological sites for the building of foreign-funded luxury development projects.[10] There is almost no government funding or support for archaeology in Lebanon, and foreign archaeological missions are rare.[11] There is no sign that the current government is attempting to overcome these economic and organizational barriers to preserving Lebanon’s ancient heritage. The Lebanese government has prioritized development (often foreign-funded) over archaeological conservation, leading to the destruction of significant sites for commercial projects, whose complete abandonment was only exposed when the port blast blew down fencing that disguised the destruction.

Beirut Downtown Seafront, 19 June 2011, Author A.K.Khalifeh, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

Starting in the early 1990s, a series of major private developments in the Old City of Beirut, on a hill overlooking the harbor, were designed and partially funded. The historical fabric of the Old City of Beirut was set to be replaced; it was rebranded as the Beirut Central District (BCD), with promises to preserve ancient sites spanning millennia.

Lebanese investigative reported Habib Battaah wrote in 2022:

“…out of at least 120 archaeological discoveries recorded in the 1990s and dozens more excavations since, less than 10 have been made accessible to the public in situ, the vast majority having vanished, either into decaying warehouses, poorly documented and thus irreparably damaged and devalued, or bulldozed entirely. A towering fifth century BC carved rock site that many believe to be one of the world’s earliest ports, was chiseled to a pulp by jackhammers in 2013 to build the Venus Towers, a series of towers designed by another Pritzker-prize winner, Spanish architect Rafael Moneo. Almost a decade later, this project too remains unfinished, having been sold to a new investor amid rumors of financial problems.”[12]

In Lebanon, the lack of state income tax revenues hampers public space projects. For instance, the multi-billion-dollar BCD project was funded by Beirut’s then prime minister Rafik Hariri and was designed to be tax-free, resulting in significant losses in potential municipal revenue. Admittedly, the costs associated with preserving cultural and historical sites is high. But that is only a small part of the problem.

Gaping pit in well-preserved Roman neighborhood for bank tower that was never built. Beirut, Lebanon. August 2020. (Habib Battah/The Public Source)

The Beirut Central District (BCD) project was launched with the promise of economic benefits and international investment. During the mid-1990s, Beirut witnessed massive construction as part of this rebuilding effort. Public sentiment at the time was marked by a sense of rebirth and new possibilities. The plan to erase much of the old city and replace it with a modern grid involved collaboration with world-renowned architects and urban planners. To showcase these ambitious plans, the project was widely promoted through billboards and commercials. The new buildings and influx of international investments became symbols of renewed hope and growth for the city.[13]

However, these reconstruction efforts were limited, as some damage could not be repaired through rebuilding alone. The lingering impact of the civil war continued to affect the country’s identity and heritage. There remained a stark contrast between the visible rebirth of Beirut and the deeper, unresolved scars of past conflicts. Lebanon’s laissez-faire economic order, rooted in colonial practices, continued to prioritize foreign investment over local development. The consequence of this strategy was the depletion of resources needed for renewal of public institutions.

Habib Battah has described how in the early 2000s, Beirut experienced an influx of tourists from oil-rich states, drawn by high-end restaurants and luxury retail outlets. However, as prices soared and the offerings became more exclusive, the Beirut Central District (BCD) was gradually abandoned by locals, leading to its underutilization. Many neighborhoods were erased and replaced with parking lots and luxury developments, while the high cost of housing kept much of the area empty.[14]

There have been many promises, all of them unmet by the government, for heritage preservation, the rebuilding of museums, and for public parks in Beirut. Since the 1990s, only a few open spaces have been built, and these are limited in accessibility and public amenities. The traditional outdoor markets in Beirut were replaced by a designer shopping mall designed by Rafael Moneo, featuring luxurious materials. In contrast, most Beirut residents live in dilapidated housing and experience severe shortages of electricity and potable water.

The architect attempted to integrate ruins into the Beirut Souks project, but these remains are largely used for decorative purposes, with archaeological finds displayed behind barriers or hidden away. A notable example was the destruction of the ancient Beirut hippodrome to build a luxury villa project, which incorporated a small portion of the hippodrome wall into a basement car park.

Site meant to house a bank tower designed by Italian celebrity architect Renzo Piano. Beirut, Lebanon. February 17, 2021. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Although all government institutions in Lebanon suffer from inadequate funding, the institutionally weak Directorate General of Antiquities (DGA) is especially deprived. There are only five professional archaeologists employed to cover the entire country. (A protest by archaeologists against Lebanese antiquities authorities was ineffective.) A neglected archaeological site near the DGA offices illustrates its completely inadequate funding. There is very little done to enthuse the public about the country’s archaeological and historical potential; the state antiquities authority rarely communicates with the general public about ongoing digs when there are any. Likewise, promises of modernity and public access have failed to prioritize the needs of the local population. Only billionaires and public officials see benefit.

Because of the total lack of transparency at the Department of Antiquities, the public sees nothing of the destruction of Lebanon’s ancient sites. The senior archeologist at the American University of Beirut accused the Lebanese antiquities authorities of covering up the destruction of countless sites across the country.[15] Journalist Habib Battah describes being approached secretly by archaeologists who were “desperate to save sites but fearing they will lose their jobs if they speak out publicly.”[16]

The lack of information means that ancient sites may be destroyed secretly, with impunity – not by looters seeking to harvest antiquities, but because real estate is more valuable than heritage.

Examples of deliberate destruction of archaeological sites to create spaces for development

As Habib Battah writes, “The city is full of empty ditches where ruins have disappeared to make way for speculative real estate that never materialized.”[17]

A cesspool-like crater is all that remains of the ruins of the ancient wall once encircling Berytus at Saifi Plaza in Beirut, Lebanon. August 2020. (Habib Battah/The Public Source)

In 2014, archaeologists working at the Saifi Plaza construction site found part of an ancient stone wall that once enclosed Berytus, one of the most storied capitals of the Roman empire. When Battah took photos in 2014, he hoped that the ancient site would not be entirely destroyed in the process of development. At that time, the interlaced ancient stone walls were still visible and the area of the ruins remained. The investigative reporter was threatened and driven away.

The massive explosion at Beirut’s port in August 2020 not only destroyed thousands of homes and businesses when the blast wave hit the historic center of Beirut– it also blew open the high walls that surrounded secretive construction projects. Where once there were ancient city walls beneath Saifi Plaza, there was now only a deep pit filled with filthy water. Another ancient site had been destroyed for nothing, as this building project had also been abandoned.[18]

When a new luxury building project is announced, like the multi-million-dollar Renzo Piano-designed bank tower on George Haddad Street near the edge of Beirut’s waterfront, an ancient site will disappear behind plywood and metal panel walls that are soon decorated with advertising billboards.

Roman ruins at the intended site of the Beirut History Museum. February 17, 2021. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

The intent is ostensibly to safeguard the public from wandering onto a construction site, but what happens behind them is a crime – in this case, the destruction of the well-preserved remains of a Roman-period neighborhood. It happens because wealthy Lebanese want to become even richer by building high-rise luxury apartments and business venues. And frustratingly, given Lebanon’s political and economic instability, these projects often fail to be completed. The Renzo Piano bank building was never built; what was once a Roman neighborhood is now a 40-50-foot-deep pit.

In 2018, the Beirut History Museum project, also designed by Renzo Piano, was announced. [19] The museum was planned as an all-glass structure aimed at showcasing postwar archaeological discoveries. The design concept included a live excavation visible on the lower level; its publicity stated that the museum “would inhabit the site.” During the initial excavation for the museum, a number of ancient structures were uncovered. These included well-preserved interconnected buildings, but today, the site that once held ancient Roman ruins is now replaced by a giant hole.[20]

Beirut, Lebanon. A street close to the Green Line which was a line of demarcation in Beirut. Vyacheslav Argenberg, CCA-SA 4.0, September 1, 2008

Overall, Lebanon’s turbulent history and ongoing conflicts have severely impacted its ability to protect its cultural heritage, with limited government resources and priorities further endangering these irreplaceable assets. Lebanon’s ongoing conflicts make it impossible to attract sufficient tourists to fund even the most important sites. A July 31, 2024 U.S. State Department Security Alert advises:

“Do Not Travel” …“the Lebanese government cannot guarantee the safety of U.S. citizens against sudden outbreaks of violence and armed conflict. Terrorists may conduct attacks with little or no warning targeting tourist locations, transportation hubs, markets/shopping malls, and local government facilities.”[21]

Because it is not safe for U.S. citizens, whether archaeologists, researchers, academics, or ordinary tourists to travel to Lebanon, the best place for Americans to understand and appreciate its culture today is through museum exhibitions, documentary research, art galleries and publications based upon artworks, antiquities, and ethnographic material held outside of Lebanon. There is a good deal of such material in circulation, not the least because Lebanon’s laws governing the trade in antiquities have been so loosely enforced until very recently as to barely count as laws at all.

Lebanon’s Antiquities Laws

Lebanon’s legal framework for antiquities began with the “30 Novembre 1933 Reglement Sur les Antiquités,” the first comprehensive law governing the management of cultural heritage. Understanding the evolution of these laws is crucial. Antiquities policies in Lebanon began with tolerating and licensing antiquities dealers and the tacit acceptance of Lebanon as a globally recognized overground antiquities market for the sale of both local and Iraqi, Syrian and other antiquities. Gradually, Lebanese laws became more restrictive but a black-market trade continued to flourish under the noses of authorities who took care not to investigate it.

Anjar, Lebanon, Tetrapylon, UNESCO World Heritage Site. Vyacheslav Argenberg, CCA 4.0, September 16, 2008.

Lebanon’s 1933 Reglement Sur les Antiquités replaced Ottoman regulations and was significant for governing the sale, trade, and export of antiquities in the country. The law included regulations on the sale of both immovable and movable antiquities (Articles 74-77) and allowed licensed antiquities dealers to trade in movable items under specific conditions (Articles 79-89). It also set requirements for exporting antiquities, such as obtaining permits and giving the state the right to purchase (Articles 94-107). There were penalties for illegal exports without a permit.

The 1933 law provided for paying informants 25% of fines collected for violations of antiquities laws (Article 1 of the 1934 appendix) and offered finder’s bonuses for seized antiquities. This system highlighted the role of informants in enforcing antiquities laws in Lebanon. These laws – and let’s face it, Lebanon’s quite open corruption – also created a de facto system of alternative payments for granting permissions and allowing export of antiquities from Lebanon and adjoining countries on a regular basis.

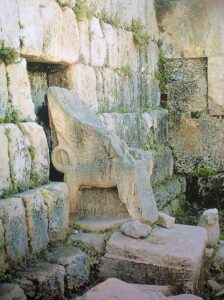

‘Astarte’s throne’ at the Eshmun temple, Bostan El Sheikh, near Sidon, Lebanon. Photo by Eli+, public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

The Lebanese government, under influence from Syria’s Assad regime, enacted more restrictive laws in the 1980s. The first general prohibition against export was the brief 1988 Ministry of Tourism Decree No. 8, issued on February 2, 1988, that prohibited the export of movable antiquities from Lebanon. There is some uncertainty about the exact publication and enforcement dates of the decree. Since its passage, the licensed, legal sales of antiquities and coins has been replaced by a grey market.

Law No. 37, enacted on October 16, 2008, was the first modern, comprehensive cultural property law in Lebanon. It expanded the definition of cultural property in Lebanon and outlined its significance. The law required documentation and registration of cultural property inside Lebanon (Articles 4-11) and imposed restrictions on the transfer and export of such property (Articles 12-14). However, the 2008 law states that it maintained some provisions of the 1933 Reglement unless they were incompatible (Articles 22 and 24). Lebanon’s historical laws remain vital in contemporary legal contexts, especially in cases involving antiquities trafficking.

Lebanon’s Request for an MOU under the U.S. Cultural Property Implementation Act

The restrictions on import and seizure and return to Lebanon under the proposed MOU of any objects entering the United States are extraordinarily broad, covering archaeological material from the Paleolithic period (approximately 700,000 years ago) to 1774 CE including everything that could possibly have been made and still exist, regardless how ordinary and duplicative these objects – for example coins – are.

The Temple of Bacchus is one of the best preserved and grandest Roman temple ruins in the world. 150 AD to 250 AD. The Baalbek temple complex. UNESCO World Heritage site. Heliopolis, Baalbek, Beqaa Valley, Lebanon. Vyacheslav Argenberg, CCA 4.0, September 16, 2008

The Lebanese government (or the U.S. State Department, which directs requests for MOUs) has also sought import restrictions on virtually every type of so-called ‘ethnographic’ object made from the 17th century to the present. i.e. 2024, including books, liturgical and religious artifacts (including Jewish and Christian materials from communities that have suffered persecution and been driven from Lebanon), as well as textiles, garments, and jewelry – and even modern and contemporary paintings by Lebanese artists. Import restrictions are also sought for rare flora and fauna.[22] The vast majority of the objects listed do not in fact qualify as of “cultural significance” under the Cultural Property Implementation Act of 1983 (CPIA).

As noted above, an obvious example of failing to meet the legal criteria is the request for import restrictions includes the works of Lebanese-American writer and poet, Gibran Khalil Gibran, the author of The Prophet. However, a far greater concern is the request for restrictions on import of common items like coins, which circulated in the hundreds of thousands throughout and far beyond the Mediterranean and Middle East in the Roman, early Islamic and Ottoman period, and the vast majority of which did not originate in Lebanon.

The National Museum of Beirut, the principal museum of archaeology in Lebanon. Beirut, Lebanon. Vyacheslav Kadisha Valley, Bsharri District, Lebanon

The UNESCO Convention assumes that nation-states are the “best stewards” of cultural heritage. However, this assumption is doubtful in Lebanon’s case, given its status as a failing state. Lebanon’s government is weak and corrupt, and has clearly failed to protect its own heritage, while real power is held by Hezbollah, a heavily armed militia associated with Iran and designated as a terrorist organization by the U.S. – and which has no concern for heritage at all.

Hezbollah’s ongoing conflict with Israel, including rocket attacks on Northern Israel and Israeli retaliations, has created a dangerous environment that threatens the survival of Lebanese cultural heritage. Due to these security risks, many countries, including the U.S., have advised their nationals to leave Lebanon.

Painting of the “Virgin Mary” with a halo from a tomb at the necropolis in Tyre/Sour, around 440 A.D. (early Byzantine period), on display at the National Museum of Beirut, Lebanon. According to Ali Khalil Badawi, director of antiquities in Tyre, it is “possibly the oldest fresco of the Virgin Mary worldwide. Roman Deckert, CCA-SA 4.0, October 6, 2019

Repatriating cultural objects to a war zone like Lebanon does not guarantee their protection. Lebanon clearly does not meet the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA)’s “self-help” requirements for protecting cultural heritage, nor do the current conditions align with the CPIA’s guidelines for international cultural property exchanges to enable U.S. citizens to have access to Lebanese culture through traveling exhibitions.

The FY 2024 appropriations legislation emphasizes the importance of strict compliance with the terms of the CPIA. There is an implied threat that Congress may cut funding if these provisions are not followed. Overall, given Lebanon’s current unstable conditions, an MOU should either be denied or heavily conditioned to prevent the misuse of cultural heritage and ensure its proper protection.

Constraints on Executive Authority under the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA)

The purpose of the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA) is to regulate the importation of cultural goods into the United States under terms set by the U.S., not the originating country. It blocks import of goods recently looted from archaeological sites or stolen from museums or other institutions. The CPIA also imposes specific procedural and substantive limitations on the executive branch’s power to impose import restrictions on cultural goods.

A place in Beirut, Lebanon that showcases old artefacts, 8 April 2016, Author U3169316, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

The CPIA outlines several criteria for imposing import restrictions. First, an artifact must be of “cultural significance” as per 19 U.S.C. § 2601. Additionally, the artifact must be “first discovered within” and subject to the export control of a specific UNESCO State Party, also outlined in 19 U.S.C. § 2601. There must also be evidence that the cultural patrimony of the UNESCO State Party is in jeopardy, as stated in 19 U.S.C. § 2602.

The CPIA also requires international cooperation and the implementation of “self-help” measures. Import restrictions must be part of a coordinated international response involving other market nations, as described in 19 U.S.C. § 2602. Furthermore, the CPIA mandates that less severe “self-help” measures must be attempted before import restrictions are applied.

Another key provision ensures consistency with the international community’s interests. Import restrictions should support the exchange of cultural property for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes in line with 19 U.S.C. § 2602.

The legislative intent behind the CPIA emphasizes that the United States should exercise its independent judgment regarding the need and extent of import controls, rather than adopting the broadest claims of ownership and value made by other nations. This is highlighted in the Senate Committee Report 97-564, which clarifies that U.S. actions should not be bound by the characterization of other countries but should be informed by our independent judgment.

Role of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC)

The Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) advises the executive branch on whether import restrictions are appropriate in general. CPAC also recommends the categories of cultural goods to be restricted, as outlined in 19 U.S.C. § 2605.

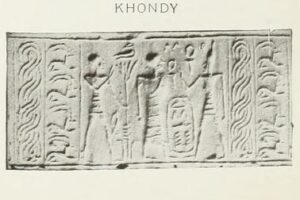

Impression of a Levantine cylinder seal bearing an ancient Egyptian royal name. Found at Byblos by Flinders Petrie (1853-1942), 18th-17th century BCE, now in the Petrie Museum. Public domain.

The restrictions placed on imports today are a far cry from the way Congress intended the CPIA to operate, which was to restrict imports when objects significant to the cultural heritage of a nation were threatened by pillage for a U.S. market. Under these terms, no import restrictions were placed on ancient coins for 25 years following the CPIA’s enactment. This was due to the widespread collection and circulation of coins, in the hundreds of thousands, even multiple millions, which made it difficult for modern nation-states to classify them as significant “cultural property.” Coins are collected globally, even inside nations that have Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) with the U.S., reflecting their proper status as items of commerce rather than protected cultural property.[23]

As it is written, the CPIA represents a careful balance between protecting cultural heritage and allowing the legitimate trade and exchange of cultural goods. Its procedural and substantive constraints should ensure that U.S. actions are measured, independent, and aligned with international norms and cooperation.

However, the United States now has very broad-based, even blanket agreements covering all items from over 5,000 to a million year period with more than thirty nations. Few of these nations make significant self-help efforts and some, like China and Afghanistan, are actively engaged in destroying the cultural heritage of religious or ethnic minorities. These perpetually renewed MOUs testify to the failure of the U.S. State Department to act fairly and faithfully within the law.

Are looted objects from Lebanon being imported into the United States? No.

Khalil Gibran, Selfportrait with muse, 1911. Museo Soumaya, photo by Benoît Prieur. CCO 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Claims that Lebanese art and cultural heritage of whatever age and value currently suffer from significant illegal trafficking into the U.S. are not factual. Christie’s auction house has sold five manuscript pages and books from the Levant in the last 10 years, worldwide. All sales were in England. Of some 350 artworks sold worldwide, all were paintings, drawings, and photographs and all were modern and contemporary artworks. A search of Sotheby’s database of auction results shows no sales of objects listed as Lebanese or Levantine at all, and Sotheby’s has held no Western antiquities sales in the U.S. since June 2015. The U.S.-based compilation site Live Auctioneers shows only modern and contemporary works associated with Lebanon, the most valuable being by Lebanese-American writer and artist Kahlil Gibran and his American grandson Khalil George Gibran.

There have been several notable recent seizures and returns of ancient objects from Lebanon. However, none of these objects were recently looted – they were taken from Lebanon 30-40 years ago during the civil war. There were several highly publicized returns of objects from Lebanon in 2023 by New York Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos’ Antiquities Trafficking Unit (ATU). Statements by the NY DA’s office made clear that the three looted objects in one return, a pair of marble statues and a bronze statuette, were outside of Lebanon thirty or more years before, exported in the 1980s and early 1990s, and that they passed through the hands of European dealers before being sold to U.S. collectors in Europe and then loaned to U.S. museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NY.[24]

Three ancient statues, including Bull’s Head repatriated to Lebanese Republic. Courtesy Office of the Manhattan District Attorney.

Another seizure by the Manhattan District Attorney of an object on loan to the Metropolitan involved a marble Bull’s Head stolen by Phalangist fighters during Lebanon’s Civil War from a storage site in 1981-1982.[25] This sculpture appears to have passed through the hands of English dealer Robin Symes to the Beierwaltes Collection in the US in about 1996. The Manhattan DA described it as having a “stunning lack of documentation” prior to 2005. It is known that the sculpture was held in the US until 2006 and then went to Phoenix Ancient Art Gallery in Geneva, which showed it at the 24th Biennale des Antiquaires at the Grand Palais in Paris in 2008. In 2009 it was reimported into the U.S. and sold by Phoenix to 2010 to Michael Steinhardt, who loaned it immediately to the Met.

Three or four objects taken 30-40 years ago do no constitute a serious state of contemporary pillage feeding a demanding U.S. market, as the CPIA statute requires.

Manhattan DA prosecutes a crime that wasn’t – and returns fake antiquities at great cost.

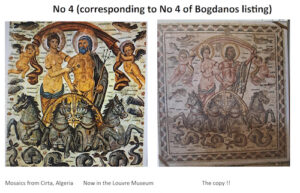

“This is Lebanon, the real Lebanon, the real face of Lebanon which we want the whole world to see: the Lebanon of art, beauty, culture, history, the Lebanon of peace and harmony between civilizations and cultures, the eternal Lebanon which will never die,” Ambassador Abir Taha Audi at return ceremony for mosaics seized from Georges Lotfi in NY, September 8, 2023.[26]

In fact, by far the largest “criminal operation involving Lebanese antiquities” in recent decades has been exposed as return of objects that for the most part were fakes.

An original Mosaic and the fake seized from Lotfi in NY. Discovered by Djamila Fellague.

A highly touted investigation by the New York District Attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit (ATU) into antiquities smuggling from Lebanon ended in scandal, although the Lebanese government has never acknowledged that the mosaics returned were fakes. It involved the seizure and return of mosaics to Lebanon and Syria, which were initially believed by the ATU to be ancient artifacts valued at over $33 million, despite their owner insisting that they were not real.[27]

The ATU and Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) led an investigation that resulted in charges against Lebanese octogenarian antiquities dealer Georges Lotfi. Lotfi was charged with Possession of Stolen Property and twenty-three other felonies. For years, the dealer had cooperated with the ATU as a secret informant, providing information on looted antiquities including a famous gold sarcophagus from Egypt purchased by NY’s Metropolitan Museum. However, N.Y. Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos alleged that while serving as an informant, Lotfi attempted to manipulate the investigators into overlooking his own illicit imports and sales of antiquities.[28]

Lotfi claimed that most of the mosaics were copies made in Syria by a known forger and asserted that the few real mosaics were legally acquired from licensed dealers in Lebanon in the 1980s. Lotfi said he discovered that most of the mosaics were fakes long after acquiring them and that he informed the ATU of this fact. In response, the ATU demanded proof from Lotfi that they were fakes, instead of conducting their own verification. Lotfi’s antiquities were seized, he fled to Lebanon, and a warrant was subsequently issued for his arrest. The email communications between Lotfi and Bogdanos show that Bogdanos refused to accept Lotfi’s claim that the mosaics were fakes unless he provided expert verification.[29]

Sculpture of a man, his wife and children, thought to be from Palmyra, Syria. Seized from Lotfi’s storage. Courtesy Manhattan District Attorney’s Office.

The New York District Attorney’s office publicly announced the return of the mosaics to Lebanon, celebrating the return with Lebanon’s ambassador as a successful recovery of valuable cultural heritage. However, art historian Djamila Fellague quickly identified the mosaics as fakes and revealed that they were blatant copies of well-known originals in global museums, a finding later confirmed by antiquities expert and former ATU volunteer Christos Tsirogiannis.[30]

The case raised questions about whether the ATU was negligent or too eager to secure a high-profile restitution. The investigation’s failure to properly authenticate the mosaics resulted in a significant waste of public resources and damaged the credibility of the ATU. The case underscored the importance of thorough analysis of objects, obtaining proof of looted origin and verifying the enforcement of national laws in high-stakes cultural heritage cases. Certainly, there is a need for greater accountability and transparency in handling antiquities trafficking investigations.

Marble Bull’s Head, proven to be stolen from archaeological storage and returned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2018. Metropolitan Museum.

A primary goal of the CPIA is to preserve archaeological sites from current and future depredations. If an MOU is approved, it should be limited to objects definitively originating in Lebanon and proven to be recently taken from sites rather than legally exported in the past under Lebanon’s laisse-faire export laws prior to 2008. Import restrictions should be applied prospectively, and to objects that meet the specifications under the CPIA, not as blanket embargoes. Finally, a system similar to the U.K.’s Treasure Act and Portable Antiquities Scheme should be implemented for managing coins and minor antiquities, to better regulate and monitor the market.

[1] The requests from Lebanon and Mongolia are for first time, 5-year agreements. The El Salvador agreement has been renewed five times already, in place since 1995. Cultural Property Advisory Committee Meeting, September 24-26 2024, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs Media Center (amended August 27, 2024) available at https://eca.state.gov/cultural-property-advisory-committee-meeting-Sept-24-26-2024,

[2] How to submit written comments: Use https://www.regulations.gov/commenton/DOS-2024-0028-0001, enter the docket DOS-2024-0028-0001 and follow the prompts to submit written comments. Written comments must be submitted no later than September 16, 2024, at 11:59 p.m. EDT.

[3] Applications to speak briefly at CPAC’s 1-hour public hearing on September 24, 2024, at 2:00 p.m. (EDT) using Zoom must be emailed to culprop@state.gov by September 16, 2024

[4] https://beirutreport.com/worlds-oldest-scale-found-in-lebanon-on-display-at-aub/

[5] “Mission reports on war damage to cultural heritage in Lebanon”. UNESCO. September 18, 2006.Archived. https://web.archive.org/web/20080220015755/http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID%3D34765%26URL_DO%3DDO_TOPIC%26URL_SECTION%3D201.html

[6] Id.

[7] Human Rights Watch, “They Killed US from the Inside,” July 3, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/08/03/they-killed-us-inside/investigation-august-4-beirut-blast

[8] “Lebanon government resigns as anger mounts,” Financial Times, August 10, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/1341b818-03ac-4f57-88eb-ddf4ef252685

[9] Hannah McGivern, UNESCO, ICOM and Louvre rally to help Beirut as museums tackle extensive explosion damage, The Art Newspaper, 17 August 2020, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2020/08/17/unesco-icom-and-louvre-rally-to-help-beirut-as-museums-tackle-extensive-explosion-damage

[10] Habib Battah, “Power, Discourse & Governance,” The Public Source, 22 March 2022, https://thepublicsource.org/searching-lebanons-ancient-ruins-capitalist-ruination

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Beirut City Museum, Beirut. https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/museo-de-la-ciudad-de-beirut-9. (Facsimile images.) See also RPBW, Ongoing Projects, https://www.rpbw.com/project/beirut-city-history-museum

[20] Habib Battah, “Power, Discourse & Governance,” The Public Source, 22 March 2022, https://thepublicsource.org/searching-lebanons-ancient-ruins-capitalist-ruination

[21] Travel Advisory of the State Department’s Bureau of Consular Affairs, July 31, 2024, Country Information Lebanon, https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/international-travel/International-Travel-Country-Information-Pages/Lebanon.html

[22] The U.S. State Department website lists the items covered in the request as follows: “Protection is sought for archaeological material from the Paleolithic period (approximately 700,000 years ago) to 1774 CE, including, but not limited to, objects in stone (such as tools, statues, figurines, sarcophagi, stelae, architectural elements, seals, amulets, objects of daily use, jewelry, and ceremonial and cultic objects), ceramic (such as vessels, figurines, objects of daily use, and ceremonial and cultic objects), metal (such as vessels, statues, figurines, jewelry, tools, objects of daily use, weapons and armor, and coins), plaster (such as wall paintings and frescoes), glass (such as vessels, seals, jewelry, and objects of daily use), bone and ivory (such as carvings, seals and amulets, jewelry, and objects of daily use), wood (such as panel paintings, icons, and objects of daily use), textiles, manuscripts (on parchment, paper, and leather), and rare specimens of fossilized fauna and flora.”

“Protection is additionally sought for ethnological material dating from the 17th century until today, including all cultural works, artifacts, and artworks (such as textiles, traditional garments, headdresses, accessories and jewelry, liturgical objects, manuscripts, books, archives, weapons and armor, and objects of daily use) crafted, made, or produced by Lebanese artists, craftsmen, writers, symbolic personalities, or made on the Lebanese territory and considered unique and representative of the diversity of the Lebanese identity and its recognition worldwide (such as works of Gibran Khalil Gibran and famous Lebanese painters).”

[23] Mark Feldman, the State Department Deputy Legal Adviser, testified before Congress that it would be challenging to justify restrictions on coins under the CPIA, noting their nature as commercial items. His testimony occurred during the Cultural Property Treaty Legislation Hearing on H.R. 3403 in the 96th Congress in 1979.

[24] Office of the Manhattan District Attorney, Press Release, “D.A. Bragg Announces Return of 12 Antiquities To The People,” https://manhattanda.org/d-a-bragg-announces-return-of-12-antiquities-to-the-people-of-lebanon/. From the press release: “Castor and Pollux: carved from white marble in the fourth century C.E., these extraordinary statuettes… passed through a number of prolific antiquities traffickers and dealers, including Gianfranco Becchina, Robin Symes, and George Ortiz, before arriving on long-term loan at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2008. They were seized by the Office in July 2022,” And “Bronze Statuette of a Worshipper: this Roman statuette of a nude athlete making a liquid offering (“libation”) was… found in a wall in the ancient city of Baalbek and smuggled out of Lebanon before appearing on the international art market in 1983 in the possession of the Geneva-based dealer-collector Jean Luc Chalmin. It was then purchased by Leon Levy and Shelby White. The Office seized the statuette in February 2023 from the Metropolitan Museum, where it was on loan…”

[25] Application for a Warrant to Search the Premises Located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.artcrimeresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Bogdanos-Bulls-Head-Case-Application-for-Turnover-Order.pdf. Association for Research into Crimes Against ArtArt Crime Research, Lynda and William Beierwaltes v Directorate General of Antiquities of the Lebanese Republic and the District Attorney of New York County.

[26] Office of the Manhattan District Attorney, Press Release, Manhattans’ D.A. Bragg Returns 12 Antiquities To Lebanon, September 8, 2023, https://www.artdependence.com/articles/manhattans-da-bragg-returns-12-antiquities-to-lebanon/

[27] Id.

[28] Kate Fitz Gibbon, “J’accuse! Georges Lotfi’s Dramatic Open Letter to Bogdanos’ Antiquities Trafficking Unit,” Cultural Property News, September 19, 2022, https://culturalpropertynews.org/georges-lotfi-dramatic-open-after/

[29] Id.

[30] Kate Fitz Gibbon, “At Great Expense, Manhattan DA Returns Fakes to Lebanon,” Cultural Property News, January 5, 2024, https://culturalpropertynews.org/at-great-expense-manhattan-da-returns-fakes-to-lebanon/ and Dalya Alberge, “US accused of sending fake Roman mosaics back to Lebanon,” The Guardian, November 19, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2023/nov/19/us-accused-of-sending-fake-roman-mosaics-back-to-lebanon

Aftermath of the Beirut port explosion, showing the destroyed grain silos and flooded blast crater. The port was also the ancient Roman center and the remains of archaeological sites were impacted. The blast caused at least 218 deaths, 7,000 injuries, and US$15 billion in property damage, as well as leaving an estimated 300,000 people homeless. Government neglect and corruption were blamed for the explosion of 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate that had been stored at the port of Beirut for six years. Photo Mahdi Shojaeian, Mehrnews.com, CCA 4.0 International license.

Aftermath of the Beirut port explosion, showing the destroyed grain silos and flooded blast crater. The port was also the ancient Roman center and the remains of archaeological sites were impacted. The blast caused at least 218 deaths, 7,000 injuries, and US$15 billion in property damage, as well as leaving an estimated 300,000 people homeless. Government neglect and corruption were blamed for the explosion of 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate that had been stored at the port of Beirut for six years. Photo Mahdi Shojaeian, Mehrnews.com, CCA 4.0 International license.