“John Gilmore Ford, more than anyone, has assumed the mantle of the collector whose scope and ambition has a civic dimension.” Gary Vikan, former director of the Walters Museum, Baltimore, Maryland.

Few individuals become passionate collectors in their twenties, fewer still manage to build world-class collections in their early years, and fewer will have the pleasure of spending many decades refining and studying their chosen field of art with a partner who shares their interests and their commitment to public museums. You have to be blessed by being in the right place at the right time and very lucky in love. John Gilmore Ford says that he is both of these.

Cultural Property News spoke with Committee for Cultural Policy board member John Gilmore Ford about his lifelong dedication to collecting and sharing the arts of India, Nepal, and Tibet.

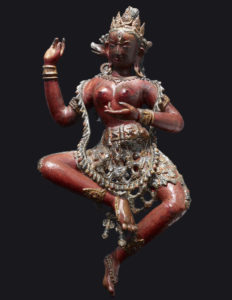

Vajravarahi, Nepal, 15th C, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Gift of John and Berthe Ford, 2017.

Ford described how his career as a designer and professional appraiser led him not only to appreciate the beauty of Asian art but also to work to ensure access to these arts for the U.S. public, first through his membership in the acquisitions committee of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, then as a trustee of the Freer-Sackler museums, and as a trustee of many years standing at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

Ford has not only served the American art community, but also spent eight years as chairman of the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust, a non-profit group dedicated to the rehabilitation and restoration of traditional architecture in Nepal. His most recent involvement with the Committee for Cultural Policy stems from his desire to preserve artworks from Tibet for both spiritual and scholarly understanding and his commitment to free public access to art. To this end Ford has also been active in opposing the continuing renewals of the U.S. cultural property agreement with China. For John Ford, preserving traditional culture also means keeping it from falling under the control of dictators whose real goals are to destroy it, as the Chinese government has done to the people of Tibet.

Smiling, Ford says that he has the highest authority for his perspective on collecting Tibetan art. Then in a more sober vein, he continued:

“As you may remember I sat on the board of the Freer-Sackler for 10 years. This was under the administration of Secretary Robert McCormick Adams. You also know that he had a strict archeological response to collecting art, which started during his days at the Univ. of Chicago. During his Washington days, the Dalai Lama was visiting America as he usually does once a year. He invited the Dalai Lama to his office to discuss the purchase of Tibetan art by American museums. The Dalai Lama responded that he was delighted Americans wanted to experience the arts and culture of Tibet since it was under siege by the Chinese. He therefore gave solid encouragement to American museum directors and their Asian art committees to collect Tibetan art, primarily painting and sculpture, which the Freer-Sackler then proceeded to purchase a few serious early pieces of sculpture. Berthe and I gave two pieces to the Freer as a direct response to this announcement.”

Exposed early to art through parents’ collecting

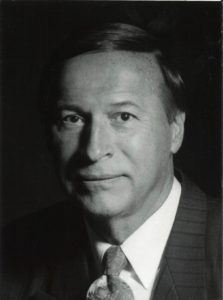

John G. Ford as a young man.

When asked what most inspired him to become a collector, Ford described his childhood in Baltimore as growing up surrounded by Asian art. Both his father and his mother collected Chinese decorative arts. In their home, art was not just for adults. “My parents inculcated in me a desire for visiting museums and private collections from childhood.”

Ford also credits his godfather, Edward Choate O’Dell, a prodigious Chinese snuff bottle collector, for encouraging him to collect. John says that, his godfather “was called by many a renaissance man as he was steeped in the world of engineering, law, music, and the collection of Chinese art.” These influences he said, “fortified me in the ability to make judgments about the arts that were foreign to my training but resonated in my mind and heart.”

The influence of his parents’ collecting and that of Edward Choate O’Dell is still very present in Ford’s life. Ford is a past President of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, of which his godfather was a founder (originally, as the Chinese Snuff Bottle Society of America) in 1968. In 1969, the organization began to publish scholarly articles and appreciations by connoisseurs on the subject. Today, Berthe Ford is President of the Society. The Society holds an annual international convention and has published a journal virtually since its inception. John Ford, one of the journal’s earliest authors, is still contributing to it.

First travels to India

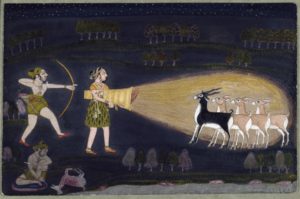

A Deer Hunt, Jegdish Mittal, Hyderabad, India, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore Gift of John and Berthe Ford, 2000.

Ford graduated from Johns Hopkins University and the Maryland Institute College of Art with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree before setting forth upon a career in interior design in the early 1960s. But Ford was fascinated with India and the mysteries of Indian art. He wanted to travel, and to acquire examples of Indian art, but was a little nervous about getting his acquisitions home. (At that time, the exigencies of foreign shipping were the concern, not cultural property laws.) Ford went to the family banker, who offered him a letter of credit far beyond the young man’s expectations – with it, Ford says, he cut a much more impressive figure in India’s antiques galleries than he deserved.

In 1963, Ford made his first visit to India. It was an excellent time to be acquiring not only Indian but also Nepalese and Tibetan art. India was full of Tibetans escaping China’s invasion of their homeland, many of whom carried with them the treasures of their homes and monasteries.

(The greatest destruction of Tibetan monasteries and temples took place prior to the Cultural Revolution during the “democratic reforms” after the 1959 rebellion, which reduced the monasteries and temples in Tibet from about 2700 in number to about 500 in the mid 1960s. After the 1966-1978 Cultural Revolution, there were only eight monasteries remaining. Overall estimates state that approximately 98% of Tibetan monasteries were destroyed. Only some 200 have since been rebuilt, and these are under strict surveillance.)

Buddha Preaching, Gandharan, 3rd century CE, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Gift of John and Berthe Ford, 2012.

Ford recalled going to a gallery of Indian antiques in New Delhi, full of Hindu and Mughal miniatures and decorative arts. He asked the owner if he had any Tibetan materials and the owner directed him to an upstairs storeroom where there were more than a hundred antique thangkas laid out in piles on the floor. Ford says, “I chose the ten most beautiful to my eyes, brought them down to the owner, and paid about $1200 for the group.” As he would later realize, these extraordinary examples of Tibetan painting ranged from the 12th to the 17th century and formed the foundation of a Tibetan collection of hundreds of paintings, book covers, and sculptures. His purchases were shipped directly to Baltimore by the gallery owners he dealt with; he was cautious about their loss in transit and always arranged for the dealers to be paid when the artwork arrived.

Ford made three trips to the subcontinent in the 1960s to study and acquire artworks, always, he says, “spending more than I had.” He displayed them in his rooms in the family house in Baltimore. One day in 1970, Edward S. King, the former director of the Walters Art Gallery (as it was then known) came on a social visit to his parents. “As he was leaving, going out the door, I asked him if he’d like to come up and see some of the things I had been collecting in India and Nepal. At this time, I had over a hundred and fifty objects – Hindu, Mughal, Nepalese and Tibetan. He agreed to stay and take a brief look. He was there for hours. I did not really expect anything after he left, but very soon after, a letter arrived from the museum’s director, Richard Randall, asking if I would show my collection at the museum in 1971.”

A first exhibition leads to lifelong passion… including for art

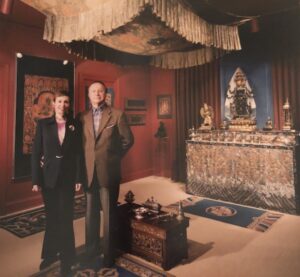

John and Berthe Ford standing in a Tibetan shrine within their home, 2001.

This first exhibition in 1971, “Indo-Asian Art from the John Gilmore Ford Collection,” with a catalog written by the scholar Dr. Pratapaditya Pal, had consequences as momentous as they were unexpected. The exhibition enabled Ford to expand his connections among a community of savants that would help to guide and inform his future collecting and marked the beginning of his long association with the Walters Museum. By far the most important and serendipitous relationship resulting from the exhibition was Ford’s meeting with a young woman at the exhibition’s opening: Berthe Diane Hanover, a Paris-born translator at the United Nations, a doctoral candidate in political science, and herself a collector with an interest in Indian and Himalayan art. She was elegant, erudite, and beautiful – and she enthralled the young collector. He pursued her and they were married in August of 1972.

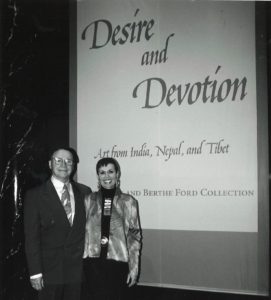

Thirty years later, the Fords wrote in the preface to the catalog for a monumental 2002-2003 travelling exhibition, “Desire and Devotion, Art from India, Nepal and Tibet in the John and Berthe Ford Collection”:

“Our meeting that night resulted in a marriage expressing desire and devotion that has enriched and ripened over the past thirty years. The love of South Asian art brought us together and still binds us in inexpressible ways. The results of our union speak for themselves in the paintings and sculptures that are photographed and described in this catalogue.”

Berthe and John Ford at the entry to the exhibition held at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, CA, 2002.

Today, John Ford adds, slyly, “I always say that I am Desire, and she is Devotion.”

Turning serious, however, he points out that Dr. Pal, who knows the Fords very well, writes eloquently about their relationship in terms of the essential themes of the art they have collected:

“This presentation some four decades later is the outcome of the intense desire and passionate devotion of both Fords, a perfect mithuna…”

Professional and museum work go hand in hand

Building and refining a collection is the work of a lifetime, but it is work interspersed with more mundane duties and obligations. With both his wife Berthe and Dr. Pal as colleagues in his collecting endeavors, Ford moved on in his profession, founding the John Ford Associates design studio in Baltimore and becoming a Senior Appraiser of the American Society of Appraisers.

Ford also became deeply involved in the museum world. Since 1980 he has served on the South Asian and Himalayan Acquisitions Committee of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. For ten years, Ford was also a Trustee of the Freer-Sackler Museum. In 1983, he founded the Friends of the Asian Collection at The Walters Museum and since 1986 he has served as a Trustee (now a Trustee Emeritus) at the Walters.

John and Berthe Ford continued to travel to learn more about the works and the cultures from which they came. Their collecting became more focused upon acquiring exceptional artworks from earlier collections in Europe and the U.S., on discovering new varieties of form and expression and upgrading the collection. They shared their artworks with scholars and worldwide experts in the field, and their acquisitions continued with the astute guidance of Dr. Pal, Hiram W. “Woody” Woodward, Jr., curator of Asian art at the Walters Art Museum, and other valued friends and colleagues.

When the traveling exhibition Desire and Devotion was completed, the Fords presented over 200 Indian, Nepalese and Tibetan sculptures and ritual objects, Indian paintings and Tibetan religious artworks to the Walters Museum for its permanent collection. These are now housed in the Arts of Asia: Art of India, Nepal, and Tibet – The John and Berthe Ford Gallery, celebrated with the Walters Museum’s grand reopening in 2001.

Bhairava, the angry manifestation of Shiva. In Nepal, he is popular with both Hindus and Buddhists and is also known as Mahakala. Nepal, 18th C. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Gift of John and Berthe Ford, 2006

John and Berthe Ford also believe strongly in fostering the appreciation for the history and early cultures of the subcontinent and the Himalayan region among the people living there today. Architectural historian Eduard Franz Sekler, a Professor of Architecture and of Visual Art at Harvard University, had worked with UNESCO on projects around the world, including UNESCO’s Masterplan for the Preservation of the Cultural Heritage of the Kathmandu Valley. In 1991, Sekler founded the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT), a non-profit organization dedicated to safeguarding the architectural heritage of Nepal. Following Sekler’s decision to retire in 1996, Ford took over as chairman of the organization.

KVPT participated in some fifty projects during Ford’s eight-year tenure, preserving and restoring monuments temples, and historic houses ranging from Buddhist votive structures of the 7th century AD to the medieval monuments and more modern structures with Moghul and even European influences. Although a number of structures restored by KVPT were destroyed once again in Nepal’s recent catastrophic earthquake, Ford points out that the expertise gained by KVPT in rebuilding structures damaged from an even worse earthquake in 1934 is foundational and will continue to be needed in this geologically unstable region.

Commitment to freedom of religion and religious expression

Dr. Gary Vikan, the President of the Committee for Cultural Policy, was most pleased to welcome John Gilmore Ford to CCP’s board because, as he had written many years before: “John Gilmore Ford, more than anyone, has assumed the mantle of the collector whose scope and ambition has a civic dimension.” This civic commitment – a global commitment to preserving traditional culture, independence, and human rights among all peoples, especially those of persecuted religious minorities, was expressed by Ford in a strong statement issued to the U.S. Department of State in 2018 on the renewal of an agreement giving the government of the Peoples Republic of China total authority and control over the circulation of Chinese art to the United States:

“Almost daily we read about China’s aggressive policies to kill and maim Tibetans, Uyghurs, and Christians. Our State Department has taken complicit positions negative for American collectors, museums and dealers, while at the same time China has opened the flood gates in their own country for the new entrepreneurs to construct many new museums and pay the highest prices ever known for the cultures they are seeking to kill. Thus far, it appears that the US State Department is more interested in appeasing China than standing up for human and intellectual property rights for everyone. Obviously, I am opposed to the State Department’s renewal of any policy that promotes the above described picture.”

Privileged as he has been to possess these threatened objects for a time, Ford says that he has ultimately been most blessed by his ability to share his and Berthe’s passion for the artworks with the public and to ensure their access through public institutions. His hope, he says, is to continue to nurture independent and uncensored scholarship, to preserve the region’s art and to bring these great works of art to the public.

Mahakala, Wrathful Diety, Tibet, 15th century, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Gift of John and Berthe Ford, 2015.

Mahakala, Wrathful Diety, Tibet, 15th century, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Gift of John and Berthe Ford, 2015.