The J. Paul Getty Museum is returning a bronze head of a young man, believed to date back to around 100 BC – 100 CE, to Turkey. The unknown model for the sculpture has short, curly hair and his face shows traces of a scant, youthful beard. The artifact, displayed at the Getty Villa Museum in Los Angeles for over 50 years, is being turned over to Turkey based upon information received from the New York County District Attorney’s Office. The museum’s director, Timothy Potts, says that the decision aligns with the Getty’s policy to return items suspected of theft or unlawful excavation based on credible information.

The Philosopher, bronze, Hellenistic Greek or Roman, circa 150 BCE to 200 CE, Cleveland Museum of Art.

Acquired in 1971 from the Swiss art dealer Nicolas Koutoulakis, the sculpture arrived at the museum with its head detached from the body. While the body’s origin remains unknown, researchers are said to have linked the head to the archaeological site of Bubon in Turkey’s Burdur province. This connection stems from illicit excavations by villagers during the late 1960s that uncovered various ancient bronzes subsequently sold overseas, many depicting Roman emperors and their kin.

Notably, the youth’s idealized features do not correspond to any known imperial family member or individual. The decision to return the artifact followed a request from Manhattan Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos’ Antiquities Trafficking Unit.

In the last several years, there have been numerous claims by Turkey that major bronze sculptures that have been in U.S. museums for decades were taken illegally from the Bubon site.

The Cleveland Museum of Art is currently contesting a claim from the Manhattan Antiquities Trafficking Unit for one of its most famous artworks. Turkey now claims that a larger than life-size, headless bronze statue acquired by Cleveland in 1986 for $1.85 million was from the Bubon site. The over-six-foot tall sculpture is a cornerstone of the museum’s ancient Roman art collection.

The Cleveland Museum has a history of returning ancient artworks to their countries of origin upon uncovering evidence of illicit activity. In this case, the museum says there is insufficient evidence for Turkey’s claim and that the New York District Attorney has failed to show that the museum does not have rightful and legal ownership of the artwork. No recent movement in this case has been announced.

Metropolitan’s Sumerian Bronze Will Go to Iraq

The Metropolitan Museum of Art announced on Tuesday that it has repatriated a Sumerian sculpture dating back to the third millennium B.C. to Iraq. This action reflects the museum’s intensified efforts to review the origins of items in its collection. The ancient artifact had been in the museum’s possession for nearly 70 years.

Man carrying a box, possibly for offerings, ca. 2900–2600 B.C.

Sumerian, Early Dynastic I-II, Copper alloy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1955.

In announcing the return, Met director Max Hollein emphasized the institution’s commitment to responsible antiquities collecting and collaboration with Iraq. Last year, the Met announced a significant initiative to scrutinize its collections for looted art, leading to the hiring of a provenance research team, which will be headed by Lucian Simmons, formerly vice chair and head of Sotheby’s restitution department.

During the Early Dynastic period (2900–2350 B.C.) in Mesopotamia, each city worshipped a patron deity, whose temple, constructed on a raised platform, served as a prominent landmark. These temples functioned as ritual centers, while also employing a large workforce for agricultural and manufacturing activities and facilitating trade with distant regions.

The depicted nude figure, carrying a box on his head, likely represents a priest bearing offerings, possibly foundation deposits or items related to temple construction rituals. Temple construction involved elaborate ceremonies, including purifying the temple site and dedicating foundation deposits to the deity.

Museum officials did not specify the research that prompted the return of the copper alloy sculpture. It had been part of the museum’s collection since 1955, when it was purchased from the highly respected art dealer Elias Solomon David. It has been studied for decades and published numerous times by noted scholars. It was displayed for many years at the Met, until its gallery was closed for renovations in 2023.

The Met cast no light on why an object was returned that was so extensively published and exhibited, with a 70-year history in the U.S., and purchased from a well-known art dealer who was the source of many important objects in American collections.

Apparently, following provenance research, the museum concluded that the sculpture rightfully belongs to Iraq. Subsequently, the museum met with the Ambassador of the Republic of Iraq to the United States, Nazar Al Khirullah, and offered to return the work. The statue’s return was commemorated with a ceremony in Washington, D.C., attended by Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani.

The History of a Palmyra Relief

Hadirat Katthina, daughter of Sha’ad ca. 200 CE, Palmyrene. J. Paul Getty Museum.

The same art dealer who originally sold the Sumerian copper-alloy figure, Elias S. David, was also the original source of a Palmyran relief acquired by the Getty in 2019 after at least 79 years in the U.S. The early history of this relief shows how differently the acquisition of art from the Mediterranean and Near East was viewed at the time. Its specific exhibition history also demonstrates that many foreign nations were not interested in claiming these ancient artworks at the time that they were brought to the U.S., published, and entered well-known collections.

In 2019, the J. Paul Getty Museum acquired a relief portrait from the Metropolitan Museum of a woman named Hadirat Katthina from the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra, dating to around 200 to 220 AD. The portrait, part of the city’s rich funerary tradition, features an inscription in Aramaic identifying the woman as the daughter of Sha’ad. Shown as she would wish to be seen in life, the woman, Hadirat Katthina, is erect, elegant and composed. Her face is proud, with striking, even piercing eyes. The fingers of one hand delicately clutch the edge of her flowing head covering and wrap. Her other hand is beringed and gracefully extended in an almost balletic gesture. It is a portrait that speaks eloquently of the wealth of Palmyra and its inhabitants.

Palmyra flourished during the first three centuries AD as a hub for the extensive trade between the Roman empire and the lands to the East. Its merchants adorned the city with temples and elaborate tombs containing portraits of the deceased carved into limestone slabs and reflecting the city’s prosperous and cosmopolitan culture.

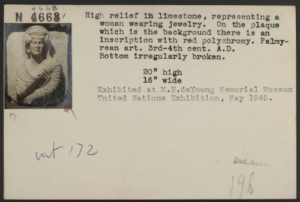

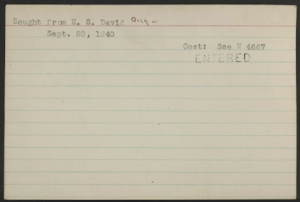

The Brummer Gallery Records N4668: Palmyrean high relief in limestone, representing a woman wearing jewelry. Metropolitan Museum of Art Part 1.

According to its record card in the Metropolitan Museum, the relief is known to have been in the U.S. since at least September 28, 1940, when New York dealer Joseph Brummer acquired the funerary portrait of Hadirat Katthina from Elias Solomon David. Following the Second World War, the artwork was exhibited at the May 1945 United Nations Exhibition at the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco, which showcased the art of the 49 nations whose delegates convened in the city to draft the United Nations charter.

The relief was offered at auction in the Parke-Bernet Galleries in 1949, then offered again in 1964 remaining unsold. It was eventually donated to the Metropolitan Museum in 2016, by John Laszlo, nephew of Ella Baché Brummer, wife of Ernest

The Brummer Gallery Records N4668: Palmyrean high relief in limestone, representing a woman wearing jewelry. Metropolitan Museum of Art Part 2.

Brummer and was located in The Cloisters Archives. It made its way to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles in 2019. It is to be hoped that Hadirat Katthina will long remain there.