According to recent DNA skeletal research, Viking warrior women really did exist. For centuries legends have told of fierce Nordic women like the Valkyries immortalized in Die Walküre, the second opera of Wagner’s famous Ring Cycle (Der Ring des Nibelungen). Shieldmaidens, the subject of Norse saga, were thought to have fought valiantly alongside men. Now, with the help of DNA evidence, new light has been shed on the question of whether such fierce female Vikings really did exist.

Certainly , there is literary evidence dating back to around the 12th century for female warriors. In a Greenlandic poem quoted from the study “A female Viking warrior confirmed by genomics,”

Then the high-born lady saw them play the wounding game,

she resolved on a hard course and flung off her cloak;

she took a naked sword and fought for her kinsmen’s lives,

she was handy at fighting, wherever she aimed her blows.

The Greenlandic Poem of Atli (st. 49) (Larrington, 1996)

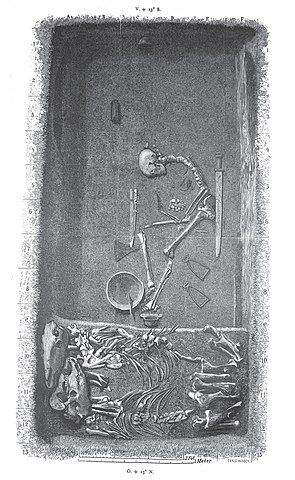

In 1889, Archaeologist and ethnographer Hjalmar Stolpe discovered the 1,000 year-old skeleton of the warrior in question at the Viking Age site of Birka, on an island in the country that is now Sweden. What Stolpe thought he found was a prominent male Viking warrior in full regalia. A skeleton was entombed with two horses, two shields, a sword, an ax, a spear, arrows and a battle knife, as well as a gaming board and gaming pieces that were commonly used in battle strategy. The importance of the burial, and its site in an elevated spot between the town and a hilltop fort, encouraged Stolpe’s belief that this was the tomb of an important man. It would take 128 years to confirm that what Stolpe actually found was a prominent female Viking warrior.

Suspicions that the skeleton (Identified as Bj 581) was that of a women emerged with the osteology reported at a conference in 2014. Swedish researchers led by Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson, funded by Swedish Research Council (VR) & Riksbankens jubileumsfond (RJ), have published a study in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.1 The physical evidence was summed up: “The greater sciatic notch of the hip bone was broad, and a wide preauricular sulcus was present [a notch on the hip bone that is more prominent in females]. This, together with the lack of projection of the mental eminence on the mandible [part of the chin], assessed the individual as female. Additionally, the long bones are thin, slender and gracile which provide further indirect support for the assessment.” Additional analysis placed the skeleton at about thirty years of age at the time of death.

To confirm the gender of the warrior, samples were taken from the left canine and the left humerus. Using a complex combination of DNA analytical techniques, the warrior was shown to lack a Y chromosome, indicating that she was undeniably female – a reminder that a little DNA evidence goes a long way.

Because the burial was consistent with that of a male warrior, the research community was initially skeptical. Skepticism works both ways, however. It was assumptions founded on contemporary society that influenced the initial incorrect identification as male. In the study, the genomic researchers have urged the need for restraint in making assumptions about gender roles in the social order of ancient societies: “The identification of a female Viking warrior provides a unique insight into the Viking society, social constructions, and exceptions to the norm in the Viking time-period. The results call for caution against the generalizations regarding social orders in past societies.

(1) Hedenstierna-Jonson C, Kjellström A, Zachrisson T, et al. A female Viking warrior confirmed by genomics. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2017;00:1–

Sketch of archaeological grave found and labelled “Bj581” by Hjalmar Stolpe in Birka, Sweden. Published 1889, By Hjalmar Stolpe [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Sketch of archaeological grave found and labelled “Bj581” by Hjalmar Stolpe in Birka, Sweden. Published 1889, By Hjalmar Stolpe [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.