Looting is always ugly. No one should support looting, ever. False accusations of looting, however, also must not be tolerated. This is especially true when they come from the Egyptian government, which ought to know better. Selling antiquities found in the ground has been a legal, even licensed, business in Egypt for much of the last 200 years, and many hundreds of thousands of objects have been traded internationally during that period.

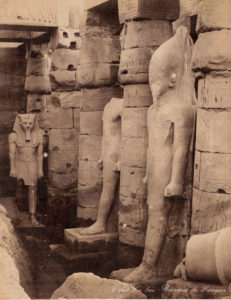

Memphis, Egypt, 19th C.

By ignoring this history, the present Egyptian government has often tried to scapegoat Western art dealers and museums and to blame the antiquities trade for its internal archaeological crises. Such claims are disputed by Egyptian officials such as former Antiquities Minister Mamdouh al-Damaty, who has stated that most Egyptian artifacts abroad had been legally exported, but they seem to recur with depressing frequency whenever Egyptian objects are publicly sold.

Just days before the opening of The European Fine Arts Fair (TEFAF) in New York on October 27th, 2018, the Consulate General of the Arab Republic of Egypt in New York sent a letter to fair administrators demanding to be given photographs and documents of all Egyptian items sold there in order to ensure that the items were legally owned and exported. In justification, the consulate stated that unnamed exhibitors at the fair had previously exhibited looted Egyptian antiquities and “that [a] number of those antiquities, illegally possessed by ***REDACTED***, have been repatriated to Egypt.” The letter, termed a note verbale by the Consulate, was cc’d to Matthew Bogdanos at the office of the Manhattan District Attorney.

TEFAF administrators informed all of the U.S. and international art dealers, who had rented booths at the historic Park Avenue Armory, of the contents of the letter. They asked exhibitors “to be ready to produce (on short notice) all the relevant documents for each Egyptian antiquity that you intend to display,” and to be sure of their “compliance with all applicable laws and regulations.” The TEFAF administrators also said they had responded to the consulate to clarify that TEFAF is a fair, not an auction, and therefore does not have photos and description of the items to be sold.

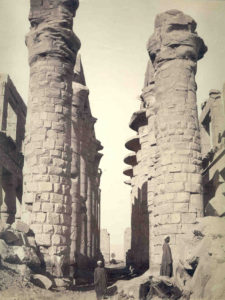

Egypt, Man with inscription, 19th C. stereo image.

At least one exhibitor, Alan Safani of Safani Gallery Inc., responded with outrage that the Egyptian consulate should demand photographs and proof of legal ownership without cause. He noted that Egyptian law allowed legal export of antiquities until 1983, and that the Egyptian export licenses the Consulate said should be shown as proof of legal export are usually summaries of large lots, and fail to itemize or describe items. Safani asked that TEFAF’s management respond immediately to counter Egypt’s excessive and legally unwarranted claims.

TEFAF CEO Patrick van Maris Van Dijk stepped in to assure the exhibitors of TEFAF’s support and Safani reported to his fellow exhibitors that the TEFAF New York team would be vigilant in “protecting the dealers from unwarranted harassment by unsubstantiated claims of countries or local enforcement officials.”

There were no seizures, attempted seizures, or claims raised about any Egyptian antiquities at the fair. However, the Egyptian government’s allegation that exhibitors should have documentation “in order to ascertain that the exhibited Egyptian antiquities were legally exported out of Egypt and accordingly, enable to repatriate artifacts that were illegally exported out of Egypt,” is contrary to the facts of the historic Egyptian antiquities trade.

Regardless of the possible approaches to Egypt’s archaeological history, which range from the colonial to the revisionist, Afro-centric, and national-enlightenment narratives, the simple facts of the history of the trade tell a different story, and are worth summarizing in brief.

Groundbreaking Study of Egyptian Antiquities Trade

Many hundreds of thousands of Egyptian objects have been exported legally from Egypt. An important academic study by Danish scholars Frederik Hagen and Kim Ryholt, The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930, The H.O. Lange Papers,[i] sets forth the commercial grounding for the wide circulation of Egyptian art in trade today.

Temple of Ramses, Luxor, Egypt, 19th C.

This comprehensive study of the antiquities markets in Cairo, Kafr el-Haram at Giza, Qena, Luxor, Alexandria and other locations, makes clear the vast scale of the antiquities trade. It covers the laws enacted and other attempts to regulate it, and the ways in which the antiquities trade was integrated into the operation of the Egyptian government’s Antiquities Service, which itself became a major vendor supplying tourists and visiting collectors.

Utilizing the contemporary records and research of Danish Egyptologist H. O. Lange, Drs. Hagen and Ryholt show that the majority of Egyptian items in museums around the world are not from archaeological excavations, rather, the vast majority were acquired from dealers in Egypt.

The first significant trade coincided with the invasion of Egypt by Napoleon Bonaparte and the development of early European studies of Egypt by scholars such as the philologist Jean-François Champollion. The first Egyptian legislation, the 1835 High Order of Muhammad Ali, attempted to regulate the rampant destruction of sites in the early 19th century by unrestricted excavation and the wholesale removal of monuments, but the controls set forth in that law were little regarded. The “museum” created by the 1835 Order failed, as its collections were repeatedly depleted by being given away to visiting foreign dignitaries.

From the mid-19th century until the trade became licensed in 1912, a network of Egyptians and foreigners acted as quasi-diplomatic “consular agents” (who generally had no official connection to the countries they represented). The chief task of the consular agents was to supply antiquities to foreign buyers; the agents contracted with diggers, and removed monumental statues virtually to order.

The consular agents’ quasi-diplomatic status generally insulated them from official government control, although their more humble suppliers were often arrested for unauthorized digging or thefts from tombs. Excavation permits were issued to antiquities dealers by the 1880s and formalized under law in 1891. As representatives for foreign sponsored excavations, the agents also facilitated the transfer abroad of a portion of all excavated items after division with the Egyptian Antiquities Service.

The Antiquities Service built very large collections of objects through excavations, chance finds, and the division of archaeological spoils with foreign excavators. A salesroom was established by the Antiquities Service in the 1880s, ostensibly to sell surplus items from the museum storage, but the business developed so well that the Antiquities Service began making archaeological expeditions specifically to supply it with objects to sell. Sites known as good sources for bronzes and amulets were among those quarried by the Antiquities Service.

Egypt, 19th C.

Hagen and Ryholt describe how a Danish archaeologist expressed a desire to purchase a mastaba, after which the Antiquities Services secretary-general James Edward Quibell invited him to choose from a selection of three of them from Saqqara. (The Antiquities Services retained its salesroom for antiquities until 1947 according to one source – through most of the 1950s in another.)

Key suppliers to foreign museums and collectors were the antiquities dealers’ shops in Cairo. These sold thousands of scarabs, pieces of jewelry, glass and ceramic vessels, statues and statuettes, bronzes, papyri, coffins and coffin lids, complete mummies, and other objects each year. A number of important shops were located adjacent to the chief European hotel in Cairo, the Shepheard’s Hotel, while nearby, a veritable palace filled with many thousands of antiquities was used as a showcase by one the most important Egyptian dealers, Louis Nahman. Many smaller antiquities shops were located in the Muski and other areas welcoming foreigners in Cairo and nearby Giza.

A 1912 Egyptian law legalized the trade in antiquities. In its first year, some 200 applications were received though only about 100 applicants qualified to receive the licenses. It appears that this was the average number of licenses active each year. The highest numbered license was #127, but the same numbers were reused for subsequent licensees. A chief purpose of the licensing process was to ensure that taxes were paid on the items sold. Receipts were issued by the licensees but as taxes were assessed by the case, not the contents, the permits provided only vague descriptions of the contents such as a dozen or a hundred or more “Egyptian Antiquities over 100 years old.”

Only in 1983, with passage of the Egyptian Law on the Protection of Antiquities, did the government of Egypt close down the official licensing of antiquities dealers that had legally supplied collectors and museums from around the world with hundreds of thousands of objects

Thus, it appears that the demand for “documents of all Egyptian items sold there in order to ensure that the items were legally owned and exported” by the Egyptian Consulate from the TEFAF exhibitors is hardly a reasonable request.

U.S.-Egypt Bilateral Agreement Requires Documentation for All Egyptian Imports

The allegation that objects being sold are recently looted Egyptian antiquities that have entered the U.S. is unsupportable for another reason. In 2016, over the strong objections of the U.S. museum community, the United States and Egypt entered into a Memorandum of Understanding restricting import of undocumented Egyptian antiquities and ethnographic objects, including the possessions of Egypt’s persecuted Christian and Jewish communities. (See Statement of the Association of Art Museum Directors Opposing Any Bilateral Agreement Between the United States and the Arab Republic of Egypt.)

Since December 5, 2016, U.S. Customs and Border Protection has enforced virtually blanket import restrictions on a comprehensive list of ancient and antique objects from Egypt, unless statutory requirements under 19 U.S.C. 2606(a) are met for each object. (These require the importer to show either documentation which certifies that exportation was not in violation of the laws of the State Party or to provide satisfactory evidence that such material was exported not less than ten years before the date of entry or on or before the date on which such material was designated.) (See Import Restrictions Imposed on Certain Archaeological Material From Egypt)

While trade in Egyptian antiquities in the U.S. is now effectively limited to items that left Egypt prior to passage of its 1983 national patrimony law, Egypt’s current El-Sisi government appears to have done little better than the previous Morsi regime to curb antiquities trafficking to the Middle East by high ranking officials, or the destruction of sites by uncontrolled building and development.

The El-Sisi regime appears more focused on celebrating Egypt’s historical greatness as a means of embellishing its present, dictatorial aims. It appears preferable to make spurious claims against the art trade, rather than address the chaotic state of Egyptian archaeological work and the millions of artifacts remaining without adequate documentation or care back home.

[i] Frederik Hagen and Kim Ryholt, The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930, The H.O. Lange Papers, Scientia Danica. Series H, Humanistica, 4 · vol. 8, 2016.

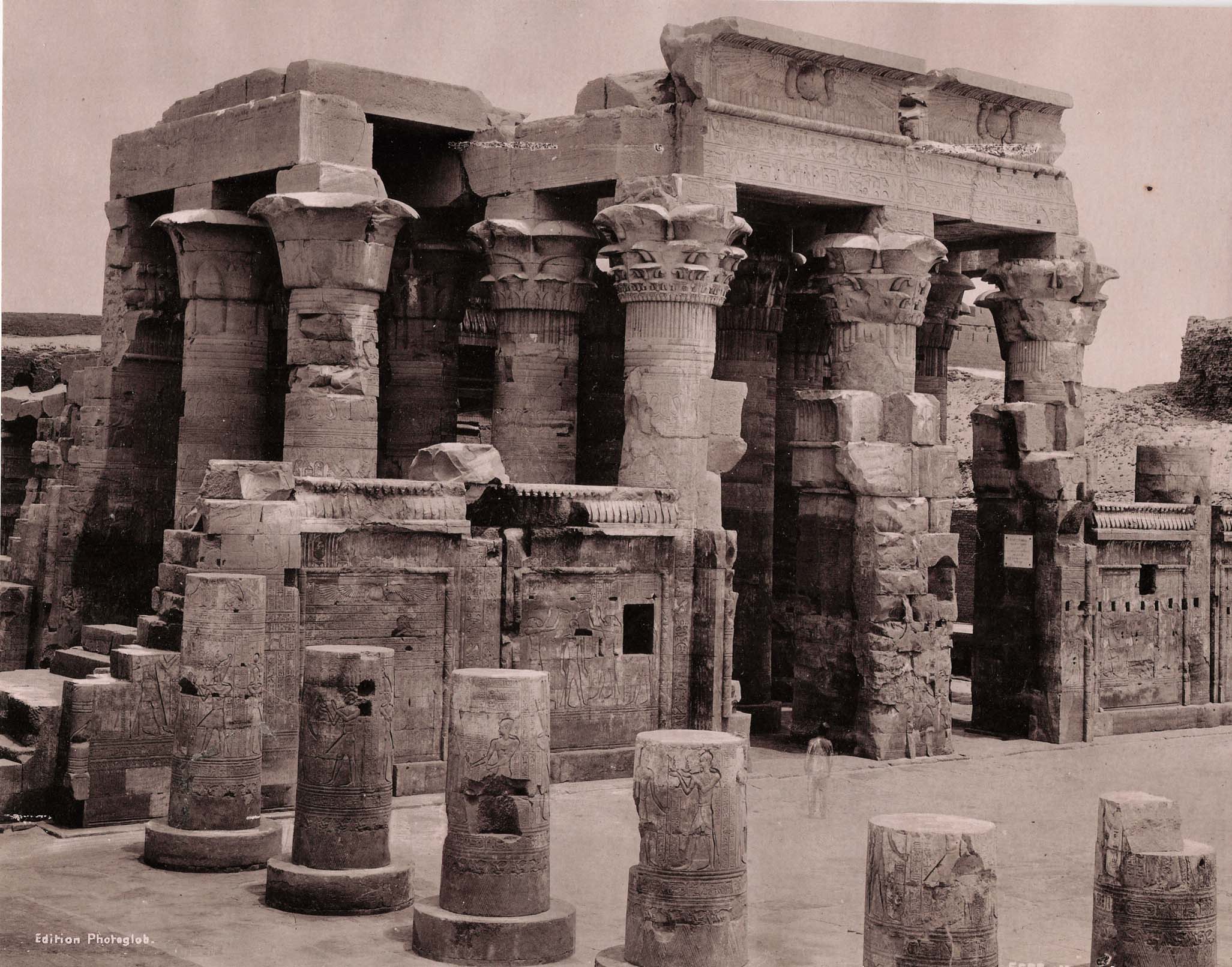

Temple of Kom Ombo, Egypt. 19th C.

Temple of Kom Ombo, Egypt. 19th C.