The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art (the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery) remains closed to the public, as it has been since the early spring. Museums and galleries across the country have struggled over the past six months to find new ways of making their art accessible and enjoyable online, while also adapting to digital platforms for the educational events that are part of most museums’ services to the public. The sad necessity of closing their doors to the public, in addition to the nationwide reckoning with historic and ongoing racism in America, has forced the nation’s museums to reconsider their own practices. There has been much discussion of how museums need to change in this new world order, not only for socially distanced art appreciation and education, but also to address the responsibilities of museums in this pivotal cultural moment.

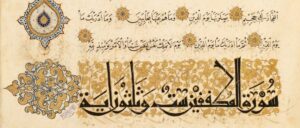

Qur’an; Attributed to Abdallah al-Sayrafi; Iran, probably Tabriz, Il-Khanid period, ca. 1330; Ink, color, and gold on paper; Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Istanbul, TIEM 487.

Meanwhile, at the National Museum of Asian Art, some of the oldest questions about the role of the art museum itself are being revisited and brushed up for the twenty-first century.

Like many national museums, the NMAA continues to provide for its temporarily exiled audience by sharing content online, including films, live talks, and free online meditation workshops. As a part of this rich array of online offerings, the NMAA live-streamed a series of three talks over the summer addressing the complex interrelationship between art, spirituality, religion, and the museum. (The program talks remain available online via the museum’s Youtube channel.)

While Grace Murray, head of public programs stated that the series was “part of an initiative to consider how we present, display, and interpret religion in our galleries and beyond,” the three talks, Moment of Zen: Buddhist Teachings for Turbulent Times (July 22nd), Conversations about Museums and Healing with Lonnie Bunch and Krista Tippett, (July 29th), and Spirituality and the Art Museum in Contemporary America (August 5th), each focused, not on the Smithsonian or its collection in particular, but on the broader question of how engagement with art can help us to a better way of thinking, acting, and being in the world.

Moment of Zen: Buddhist Teachings for Turbulent Times

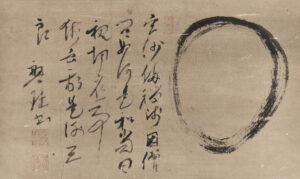

Enso, Hanging scroll: ink on paper, Bankei Yotaku, Japanese, 1622–1693, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Acquired through the Lee C. Lee Endowment for East Asian Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

The first in the series, Moment of Zen: Buddhist Teachings for Turbulent Times, featured a conversation between Zen priest Rev. angel Kyodo williams, Harvard professor of the history of art and architecture Yukio Lippit and Frank Feltens, Japan Foundation Assistant Curator of Japanese Art at the Freer and Sackler.

The phrase ‘moment of zen’ has passed into popular culture, becoming shorthand for any brief and relatively serene interlude in our busy lives. For years, Comedy Central’s The Daily Show featured an episode segment called ‘Your Moment of Zen,’ a particularly surreal or slapstick moment from week’s news, while, as the event page for this presentation noted, ‘#museummomentofzen has been trending’ over the past spring and summer.

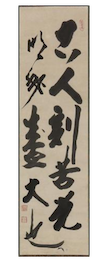

With luck, that hashtag will be back next year, during the planned 2021 exhibit “Mind Over Matter: Zen Monk-Painters in Medieval Japan,” for which this talk also operated as something of a teaser. The discussion inevitably turned to the role of art in Zen Buddhist practice. As Dr. Frank Feltens, Japan Foundation Assistant Curator of Japanese Art at the Freer and Sackler, noted, artistic exchanges between China, Japan, and Korea in the medieval period accompanied the development of Japanese Zen, contributing to the distinctive “highly codified and aestheticized” system associated with the religion, “the environment for practices of the mind.” He noted that this environment “still resonates with common notions associated with Zen today for example, almost stereotypical notions like contemplativeness, stillness, simplicity.”

Qur’an; Copied by Yaqut al-Musta‘simi Iraq, Baghdad, Il-Khanid period, 1286–87; Ink, color, and gold on paper; Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Istanbul, TIEM 507.

The same yearning for simplicity – and for an environment suited to “practices of the mind” is seen in the modern curator’s approach to exhibition design. Long gone are the lavish draperies and furnishings that decorated nineteenth-century exhibition spaces. Though the modernist ‘white cube’ style has been discredited as a universal solution for art display, a spare – that is, stereotypically Zen-style – design for art exhibitions remains the standard.

During the conversation, Dr. Feltens, Rev. angel, and Dr. Lippit discussed the lessons that can be taken from the contemporary and historical Zen practices to aid both in daily life and in museum work. The conversation returned often to the role of art in transmitting Zen ideas and in inducing a meditative state. Art, they asserted, played a key role in the development of Zen Buddhist beliefs and practices across time. Dr. Lippit suggested, apropos the prominent role of painting within Zen Buddhist communities, that “there is something about painting that communicates teachings and principles and ideas in Zen in a way that words can’t.”

The idea that art speaks with an eloquence of its own, teaching and reaching those numb to other forms of spiritual communication, is at least as old as the medieval Zen artworks under discussion. During the Counter Reformation, the Catholic Church commissioned Italy’s greatest artists to produce religious works for their churches, in the belief that the images would help to strengthen their congregations’ faith. Some of the first major public museums, in nineteenth-century England, were opened to the general public in the hope that the power of art would both civilize and uplift the spirits of their working-class visitors. We could all use a little assistance from the healing power of art in these dark times – but whether it is possible to achieve a true moment of Zen from a digital visit to any art collection, even one so serene as a compilation of Zen Buddhist works, depends largely on the state of our own minds – and the degree of Zen-like serenity we are able to create while viewing it from our own home environment.

Conversations about Museums and Healing with Lonnie Bunch and Krista Tippett

Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings from the St. Petersburg Album, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC

In so far as museums pass judgement on what kinds of object qualify as art, and what artworks merit accession and display, they are inherently hierarchical and exclusive institutions. But as public spaces, open to all for free or for a fee that rarely exceeds that charged for a 3-D film or a live sports event, they are also egalitarian. Free museums in particular can serve as a communal gathering space, a downtown extension of our own homes with comfortable benches, long hallways for strolling in, and really exceptional décor.

This event, featuring interviews with two of the most high-powered members of the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art’s management, extends that public access to the boardroom, as it were, and demonstrates that, at the highest levels, museum leaders are engaged in the same difficult conversations as the rest of the nation. Lonnie G. Bunch, Secretary of the Smithsonian, and Chase F. Robinson, the Dame Jillian Sackler Director of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and the Freer Gallery of Art, and Sana Mirza, Education Specialist and Manager of Scholarly Programs and Publications, joined author Krista Tippett and Sabrina Motley, director of the Smithsonian Folklife Festival.

These influential members of the arts industry wondered what role they and their workplaces had in fighting the institutionalized racism and bridging the social divisions highlighted by the summer of protests against injustice. Unusually, in this fraught year, the conversation focused on the positive, as all participants expressed their faith in art museums as places not only for relief from anxiety and negative emotions, but as sites capable of inspiring real change in the opinions and the behaviors of their visitors.

Dr. Robinson described museums as “an integral part of the practice of democracy.” Because they are free, and on the National Mall, the Smithsonian’s multiple museums in particular “are an integral part of how we as a nation contemplate, deliberate, and communicate with each other.”

Qur’an; Probably Turkey, Edirne, 1457–58 (AH 862); Ink, color, and gold on paper; Transferred from the library of the Hagia Sophia to the Museum in 1914; Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 30.

When discussing the National Museum of Asian Art’s role in breaking down racial stereotypes Dr. Robinson continued, “I defy someone to spend a half an hour with me, or with a curator, someone who may be committed to cultural stereotypes, I defy that person to spend a half an hour in our museum, and not leave thinking differently … I defy that person not to feel differently about Asia, Asian Americans and indeed the world.”

Earlier Dr. Robinson had described the effect of an exhibit called The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts in the fall of 2016. “It brought to the American public for the first time the extraordinary quality of Islamic calligraphy and Qur’anic calligraphy in particular, and the diversity of that tradition. Given where we were then as a nation and in some respects where we are now it was a very powerful antidote to certain misunderstandings of Islamic tradition.”

Krista Tippitt talked about museums as providing a space to rest and rejuvenate one’s inner life, in preparation for practical struggles in the world outside the museum, conserving “the resilience [needed] to do not just the immediate action, but the long-term work.”

According to Secretary Lonnie Bunch, “at a time when a nation is in crisis, museums need to be the glue that holds a nation together. To be that glue, they need to be able to talk candidly about the past, they have got to be able to give the public tools to live their lives, then we need to be able to help people find understanding, help people find clarity and if we can help people find understanding and clarity, then there is a chance we can help them find hope.” Museums, he believes, can be spaces for people to bear witness to the full hard truth of an event, to bring people together “that wouldn’t know each other, wouldn’t have anything in common,” to help them to find their common humanity, grapple with their common pain, and “to help them to find healing.”

In the midst of widespread anger directed at the failures of other institutions tasked with protecting the public interest – from law enforcement to the EPA – it is a pleasant change to hear so much optimism about the public-service capacities of the art museum, albeit from insiders.

Spirituality and the Art Museum in Contemporary America

The third program of the series asked how museums can teach their audiences about religion and spirituality, touching along the way on issues of cultural appropriation and the importance of real scholarly engagement with a work’s history, as well as its aesthetic appeal. Participants were Columbia University Associate Professor of Religion Dr. Courtney Bender, Harvard Divinity School’s Director of the Women’s Studies in Religion Program, Dr. Ann D. Braude, and Duke University’s Director of Islamic Studies Center Dr. Omid Safi. Dr. Massumeh Farhad, Chief Curator at the Freer Sackler galleries and The Ebrahimi Family Curator of Persian, Arab, and Turkish Art, facilitated the discussion.

Zen Aphorism, Hanging scroll, artist Hakuin Ekaku 白隠慧鶴 (1685-1768), Edo period, ca. 1760, Gift of Kurt A. Gitter, M.D. and Alice Yelen, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC.

The loosely-defined notion of ‘spirituality’ is not a newcomer to the discourse of the art museum. As Dr. Bender pointed out, the modern art museum now known as the Guggenheim was launched with an explicit spiritual mission as the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. Hilla von Rebay, the museum’s founding director, had worked with Solomon R. Guggenheim to build his art collection. Dr. Bender explained that, “Rebay invested in Theosophy and encouraged Guggenheim to collect works by painters that she felt embodied the values that she associated with this particular spiritual tradition of painters,” including the works of abstract art pioneer Vasily Kandinsky.

A 1939 souvenir guidebook to the museum began: “The art of Non-objective painting is spirituality made visible … [The non-objective artworks] are alive and organic with cosmic order, which rules the universe.” This kind of thing was all very well in the 1930s, or the 1960s, but we expect a more grounded approach from museums today. Nonetheless, the tendency to label a wide range of qualities in and responses to Asian art as ‘spiritual’ has persisted.

At New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), for instance, the notion of ‘spirituality’ functioned not as a guiding light but as a way to insulate key donor and co-founder Mrs. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and founding director Alfred H. Barr from engaging with the actual religious content of the works they admired. As Dr. Bender put it, “the museum’s leaders also operated with an implicit distinction between religion and spirituality that had consequences for things that happened in the museum.”

Mrs. Rockefeller’s love for Asian art, of which she had an extensive collection, was expressed through the Buddha rooms she installed in her houses, and in the Asian garden in her home in Seal Harbor, Maine, which she based on what she’d seen on her travels in Asia.

Her artistic appreciation of the objects she collected belied the fact that “Buddhism left her cold as a religion” – and yet, according to Dr. Bender, Mrs. Rockefeller often spoke of how, to her “Buddhistic art [was] the most inspiring and spiritual.” In practice, “she could embrace these objects as spiritual but not as religious. We might say that the language of the spiritual experience, perhaps, allowed her to connect with the beauty or what she understood to be the universal in an object that was otherwise foreign to her,” Dr. Bender concluded.

Dr. Bender saw MoMA’s founding director Alfred H. Barr, Jr. as having a similar sense of “disconnecting the religious and the spiritual” and “privileging what he thinks is the universal spiritual in works of art. … he would make museum displays and exhibits that would allow viewers to see the distinction between the universal and the particular as crucial to experiencing artworks,” said Dr. Bender. “This involved not only displacing material from their contexts but also orienting viewers toward what he understood to be the universal – and not toward something that was specific or historical or political or even religious.” One of the ways that this was achieved was through displaying art on white walls with space between objects to allow the viewer an intimate interaction with the artworks.

Celestial Figures, Wall Painting Gypsum plaster with pigment, Cave 224, Kizil Cave Complex, ancient kingdom of Kucha, Baicheng county, Xinjiang province, China. National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC.

Although Dr. Bender did not go so far as to characterize their behavior in this way, it seems that Barr and Rockefeller saw the religious background and content of Buddhist art as negligible, and conceptualized them instead as icons of a kind of ‘universal spirituality’ in order to remove obstacles to their ability to enjoy the objects. While this approach enhanced the objects’ aesthetic appeal, it also exemplifies the kind of superficial appropriation of cultural property that gives genuine cross-cultural exchange and art appreciation a bad name.

Indeed, Dr. Safi was quick point out the flaws in MoMA’s founders’ approach, asking, “are we conceiving of spirituality as something that can only take place by erasing and negating the particularity of different religious traditions, especially when those religious traditions happen to come from outside of the West?” He continued, “What happens to ritual? What happens to scripture, what happens to institutions, and what happens to community in our rush to move toward our understanding of spirituality?”

Dr. Safi invoked as a counterexample the shrine of Hafiz, in Shiraz, Iran. It has been a pilgrimage center in Iran for over 600 years, part of a continuous living tradition, he said, showing and explaining multiple examples of artworks depicting this tradition.

Dr. Safi also described how the works of both Hafiz and Rumi, the Islamic poets that are most familiar outside of the Middle East, are generally mistranslated and misunderstood when removed from their Muslim context. In fact, Dr. Safi noted that, “Some of the best-selling books that are attributed to Hafiz are entirely made up by an American poet, passing his own poetry off under Hafiz’s name.” And yet, in Shiraz, Iran, the shrine of Hafiz remains an important pilgrimage site, as it has been for more than 600 years. There, Hafiz’s works “are not relics of the past, there is a living community that continues to read, and recite and chant this poetry.”

As a more recent example of how the idea of ‘spirituality’ enables us to enjoy religious art without fully understanding its cultural background or religious content, Dr. Bande invoked the example of her grandmother, Jewish abstract painter Vicci Sperry, who also collected Asian art and “had very little interest in the Asian-ness of Asian art,” her granddaughter said. Instead “she valued these figures because they evoked in her a sense of stillness and tranquility.”

Hilma af Klint, Group IV, No. 3. The Ten Largest, Youth, 1907 Tempera on paper mounted on canvas, Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk. Photo: Moderna Museet / Stockholm

Early 20th century artist Hilma af Klint had experiences that transformed her classically trained art aesthetic into a disarmingly modernist form of abstraction. She was heavily influenced by Spiritualism, a supernaturalist movement that arose in the mid-nineteenth century in America and the United Kingdom. Spiritualism varied in the specific forms it took, and the degree of seriousness with which people participated in its practices. To some, it was very nearly a religion, to others a foundation for scientific study of the supernatural, to others a laughable trend espoused by the ignorant. The rise of Spiritualism popularized home seances and so-called ‘spirit photography’ – photographic prints that supposedly showed shadowy ghosts beside their living loved ones. The notion of a ‘spirit guide’ was disseminated by Spiritualist practitioners and made famous by celebrity mediums who communed with or claimed to be possessed by these ghosts from the beyond.

Hilma af Klint’s own Spiritualist practices led her to produce abstract paintings that had no counterpart in contemporary art at the time. Dr. Bande described her work, and its Spiritualist influence, as follows: “After several years of spiritual investigation, she accepted a commission from Spirit who spoke to her in weekly séance circles, a voice she understood to be the spirit of a Tibetan spiritual master. The commission required the 43-year-old af Klint to abandon her livelihood as a realistic painter, to spend a year fasting praying and purifying herself, to complete a set of spiritual paintings that would ultimately number in the hundreds. At the end of that year of preparation and discipline, while in trance, with the spirit guiding her hand she painted these ten paintings over a 6-week period. She knew that the spirit’s intent of the paintings was to convey spiritual knowledge, not just to her, but to humankind. She knew that they depicted the unseen reality that theosophists saw as the basis for all religions. They depicted, as Helena Blavatsky put it, ‘both the dual nature of every object on earth in the spiritual and material, both the invisible and the visible nature.’” An exhibition of her work at the Guggenheim in 2019 entitled Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future – showcased these ten paintings. With over 600,000 attendees, it was the most visited exhibition in the museum’s history.

af Klint’s fixation on a “Tibetan spiritual master” as her guide from the beyond anticipated, to a degree, the growing twentieth-century interest in a wide range of East and South Asian spiritual practices, from yoga and meditation to the installation of religious art, such as Buddhist sculpture, in homes and gardens. The widespread interest in af Klint today probably has more to do with her work’s surprising abstraction in an era of representational figurative art, and her status as a woman artist, than with the Spiritualist and mildly Orientalist ideological underpinnings of her work.

However, as this talk demonstrated, the notion of a ‘spiritual’ connection to art, and its association with Asian art in particular, survives into the present day. As a substitute for substantive religious, historical, and cultural understanding in academic or curatorial writing, it’s a tad suspect – but on the level of individual experience, a ‘spiritual’ connection may still be the best way to describe the way a great work of art makes us feel.

The series was made possible through generous support from the Lilly Foundation Religion and Cultural Institutions Initiative. Massumeh Farhad, Chief Curator and The Ebrahimi Family Curator of Persian, Arab, and Turkish Art, stated that the “grant was designed to allow us to consider how we present and interpret religion in the museum context. Our period of study, from April to July, coincided with the outbreak of COVID-19, the crisis, combined with our Lilly programs and conversations, has given us a renewed sense of mission, that changing the museum can be part of changing the world, where we can respectfully discuss and present topics such as religion, spirituality, and beauty, and explore ways in which these ideas have been expressed in the past according to different cultures and how they are viewed today.”

Hilma af Klint, Group IV, No. 3. The Ten Largest, Youth, 1907 Tempera on paper mounted on canvas, Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk. Photo: Moderna Museet / Stockholm

Hilma af Klint, Group IV, No. 3. The Ten Largest, Youth, 1907 Tempera on paper mounted on canvas, Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk. Photo: Moderna Museet / Stockholm