By the Fall of 2019, the Turkish government will cover 115 square miles of an ancient Tigris River valley with water now filling the massive Ilisu Dam and Hydra hydroelectric project in Turkey’s Kurdistan region. The new Ilisu dam will be one of the largest in Turkey; the government says it is needed to generate power to serve the agricultural lands surrounding it. However, in the process, communities dating back thousands of years will be destroyed along with their many architectural and historical remains.

Not only the archaeologically rich Hasakeyf region where the dam lies will suffer. The dam is also expected to severely impact communities in ancient wetlands downstream in Iraq and Syria. Although Turkish authorities state that they will prevent this by releasing 500 cubic meters of water per second from the dam, others say the amount is less than half what is promised. Already, wetland residents below the dam have abandoned their communities as traditional subsistence activities are no longer sustainable.

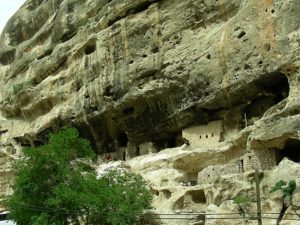

Hasankeyf, 23 May 2007, Photo by Herbert Frank from Wien, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Above the dam, the 12,000-year-old town of Hasankeyf, believed to be one of the world’s oldest cities, will be covered by the rising waters along with many smaller rural settlements. At various times, Hasankeyf has been home to Neolithic cave-dwellers, a Byzantine bishopric, Seljuk city, Arab fortress, and Ottoman military outpost. The reservoir will submerge the ancient caves (some still inhabited in the 1970s), houses, tombs, monuments, towers, and churches under almost 200 feet (over 60m) of water. More than 300 historical sites will be submerged. Yet the dam that will inundate these thousands of years of history is only estimated to last for 100 years.

The area around Hasankeyf has been occupied since the earliest Mesopotamian period, and the remains of ancient cave dwellings sit near a medieval citadel, not far from an Artuqid bridge, constructed by a Turkmen dynasty that ruled in Eastern Anatolia in the 11-12th century. Archaeologists say that the loss of the ancient landscape of irrigated fields and gardens dating to the Seljuk period also represents a serious loss of knowledge, since few such ancient rural sites exist untouched.

While salvage archaeology has been taking place since the Ilisu dam project was begun in 2006, only 15% of the sites in the area have been worked on. The rest will disappear forever.

The failure of Turkey’s government and cultural authorities to preserve the antiquities of the Hasankeyf site is strikingly different from its attitude toward Turkish antiquities in Western collections. The Turkish government has demanded return of many important objects from foreign museums, including statues taken from illicit excavations many decades before, and objects divided with the Ottoman government in the early archaeological practice of partage from sites excavated in 19th and early 20th century. Joint archaeological projects with countries where Turkish collections are located have been threatened and even cancelled.

In 2017, Turkey’s government filed lawsuits and sponsored headline-generating protests against Christie’s auction house, claiming government ownership of a 9-inch relic known as the Guennol Stargazer and alleging that this was the first time the object was known to be in the U.S. (However, curator Rafet Dinc of the state-owned Manisa Museum had written of the statuette as “known” in 1997, and cited to photos published in a 1992 article by Jurgen Seeher which identified the N.Y. collectors. The statuette had also been publicly exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of art from 1999 to 2007.)

Salvage Archaeology in Hasankeyf Not Enough

Hasankeyf, 23 May 2007, Photo by Herbert Frank from Wien, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

In Hasakeyf itself, archaeologists from Batman University in Turkey and Japan’s University of Tsukuba (Japan) have found evidence of human communities dating to 9500 B.C., and a water purification system from the 12th century.

The Turkish government has promised to move the most important architectural remains of Hasankeyf to another location above the waters and to build a museum for artifacts removed, but this and other cultural plans appear to have been limited efforts, now largely abandoned. The Tomb of Zeynel Bey has been moved, but many other important remains either have not or cannot be moved.

Hasankeyf was included on the 2008 World Monuments Watch in order to draw attention to the town’s plight, but this and other international protests have not moved Turkey’s government to reconsider. After a decade of campaigning against the dam, its residents are close to despair. Hasankeyf resident Fatima Salkan told PRI reporter Durrie Bouscaren,“We tried to protest but we could not, because they’ll call you a terrorist. If people protest, they are punished.” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan intimated the same, describing protesters and PKK Kurdish separatists as similar in 2016.

The Turkish government has constructed new housing on an unlovely, arid site higher than the dam level, offering Hasakeyf residents the chance to buy them, but residents say the cost of new homes, about $85,000 each, are eight times the value of their old homes, which were surrounded by orchards and gardens. Some families have moved to the new town, but without jobs or economic infrastructure, the chance for both the new town and the community’s cohesion and survival are slim. Hasankeyf’s town residents are poor; most make their living from sheep herding or rug weaving. The region is already economically depressed due to decades of civil strife between Kurdish separatists and the Turkish government.

Hasankeyf, 23 May 2007, Photo by Herbert Frank from Wien, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Protests and petitions have been organized by the Initiative to Keep Hasakeyf Alive, an organization with members from nearby municipalities, local environmental groups, cultural, women’s and human rights NGOs, professional associations and trade unions. The European organization Europa Nostra nominated the site as one of its seven most endangered sites in 2016. Environmentalists have voiced serious concerns as well. When the project is completed, the reduction in water flow is expected to dry up huge areas of marshland in southern Iraq and to collapse that region’s traditional ecology and its wetland subsistence economy.

The European Court of Human Rights struck the Hasankeyf community a heavy blow when it rejected arguments that protection of an individual’s cultural heritage is a human right. The Court placed responsibility for cultural heritage decisions on Turkish authorities, stating, “the Court has no jurisdiction to consider whether or to what extent the construction of a dam could undermine a cultural heritage.”

International Banks Withdrew, Replaced by Turkish Funding

The dam project began in the 1980s and has been delayed many times, notably in 2009, when European backers ordered a 180-day suspension of the project to spur the Turkish government to modify the plans to meet World Bank environmental and historical preservation standards. When Turkey failed to take steps to comply, the Austrian, German, and Swiss underwriters withdrew funding for the €1.2-billion project. Turkish banks, Akbank and Garanti Bank, have provided subsequent funding.

Alternative plans for five smaller dams that would leave Hasankeyf intact were rejected in 2014. The Turkish central government has pushed the Ilisu dam project forward regardless. The 6,000-foot-long (1828.8 meter) dam is complete and is starting to fill. Within a few months, depending on the outflow allowed downstream, Hasankeyf will have disappeared.

Hasankeyf before the inundation by the dam, 23 May 2007, Photo by Herbert Frank from Wien, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Hasankeyf before the inundation by the dam, 23 May 2007, Photo by Herbert Frank from Wien, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.