The first J. Paul Getty Occasional Paper in Public Policy is Cultural Cleansing and Mass Atrocities: Protecting Cultural Heritage in Armed Conflict Zones, published December 2017.

While Cultural Cleansing and Mass Atrocities is intended to “provide guidance about how best to pursue an international framework for the protection of cultural heritage in wars,” the 45 page paper should be required reading for everyone involved in cultural heritage from museum curators to archaeologists, diplomats and NGOs. The entire paper is available to download for free. What follows is a summary of its key points.

The authors, Thomas G. Weiss and Nina Connelly, cover much more than cultural cleansing and horrific crimes against human societies. The paper analyzes political and diplomatic history showing which policies to protect heritage have worked and which, much more often, have failed. The authors argue in favor of re-framing the international cultural policy debate, turning away from extreme nationalism and embracing broader concepts of global stewardship and international protection of heritage as a more workable approach to halting destruction in war and preserving mankind’s achievements for the future.

Destruction of the Temple of Bel in Palmyra, Syria, September 2015.

In “The Problem,” the first chapter, the authors describe how a humanist approach to protecting cultural heritage is similar to protecting human rights. They identify the responsibilities to protect human beings and to protect cultural heritage as inseparable and requiring similar policies and strategies: prevention of harm where possible, swift reaction to remedy harm when inflicted, and accepting the duty to rebuild social and physical structures going forward. “Air, water, and culture,” they say, “are essential for life.” (p6)

They argue that one perceived barrier to the protection of cultural heritage is essentially a false choice – the idea that there is a hierarchy of importance, or that the protection of people and the protection of heritage are non-complementary priorities.

The paper defines cultural destruction during a conflict in broader societal terms than international conventions have in the past. These cover (1) deliberate damage and destruction during war, including destruction as a form of “cultural erasure” or “cultural cleansing,” (2) collateral damage to cultural property inflicted in order to achieve a different goal (for example, to secure strategic resources, or to kill people hiding or barricaded in a monument, a justification used for recent Syrian bombings by its military), and (3) forced neglect, such as occurs when traditional populations are forced out of a region.

Weiss and Connelly examine the challenges to ending cultural destruction, both through “building on existing legal and normative tools” and through pursuing a “new policy norm.”

They begin with the three pillars of current international policy on cultural heritage set forth by the United Nations in 2005:

- The primary responsibility of each nation for protection of the cultural heritage within its boundaries,

- The international responsibility to fortify the states’ ability to protect heritage, and

- The international responsibility to respond in cases of egregious state failure to act.

The authors question how policies that “protect” cultural heritage can be valid when the beneficiary of that policy is not the people, but the state, and when the enjoyment of cultural heritage is not equally granted to all the individuals under the authority of the state.

Weiss and Connelly identify state sovereignty – one of the pillars of current policy – as an obstacle to developing more effective policies to prevent harm to heritage. They note that the wanton destruction of cultural heritage in recent decades has not only been perpetrated by terrorist groups and other non-state actors, but also undertaken by government forces, as in the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban and the current bombing of Yemen by the government of Saudi Arabia. Historically and today, the physical destruction of monuments has been part of government’s “effort to assert the new orthodoxy and erase history and culture” that is in opposition to their policies. (p8)

Fragment of a Funerary Stele, about 200 A.D., Limestone. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

The authors also consider the varying definitions of cultural property in international instruments. They discuss the fundamental difference between instruments that express cultural property’s universal value to all peoples (such as the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and the 1972 Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage) and instruments with a state-centric emphasis, in which the definition of cultural property is “contingent on a self-proclaimed designation by a state,“(p10) rather than considered a significant expression of human creativity and experiences. This state-oriented perspective dominates the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.

“From our vantage point,” the authors write, “the 1970 approach prioritizes the accidents of geography and the shape of arbitrarily drawn borders and contemporary political configurations…over any intrinsic value of cultural heritage for humanity as a whole.” They note that, “as the world grows smaller and more connected through the forces of globalization, modern states claim exclusive ownership over shared cultural heritage. Cosmopolitan perspectives, or cultural internationalism, become politically incorrect as cultural nationalism comes to the fore.”

Furthermore, Weiss and Connelly argue that the concept of the “universality of the value of cultural heritage enshrined in the 1954 Hague Convention does more to advance contemporary international efforts to protect cultural heritage in zones of armed conflict than state-based conceptions of cultural property.”

They therefore chose a non-statist definition of cultural property for the purpose of this paper – one set forth by James Cuno – that ascribes a universal value and importance to specific objects: “movable and immovable artifacts and immovable structures of historical and cultural significance to humanity.”

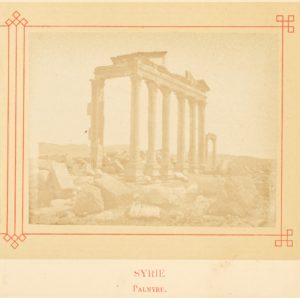

Félix Bonfils (French, 1831 – 1885) Palmyre., about 1878, Albumen silver print. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Chapter 2, “Mapping Protection, What’s Old and What’s ‘New,’” outlines the current protections for cultural property in international law and the penalties, such as they are, for violations. The authors note the absence of enforcement protocols allowing UN member states to respond to cultural destruction under any circumstances, particularly when wars are within a single country, or involve non-state actors who violate international conventions to which they are not signatories. What they see as “New” in international cultural property policy is the linking of destruction of cultural property to threats to international peace and security.

(It does concern this reader that while the authors cover international actions directed against looting and smuggling in this chapter, including the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 2347, they fail to point out that many national and international legal measures, including Resolution 2347, have been based on highly inaccurate data. Nor do they ask why the now-debunked, exaggerated value of looting for terrorist financing – once said to be billions of dollars, now a few million – assumed so much importance in the international conversation on halting terrorism, while important sources of terrorist financing were barely discussed.)

The authors have noted the unwillingness of Russia and Egypt to sign on to broader protections. Both countries opposed the initial drafts of 2347 that proposed expanding the scope of current cultural heritage endangerment beyond Syria and Iraq, and to include provisions for the protection of cultural heritage internationally in the event of any armed conflict, and not only in the context of terrorism.

Weiss and Connelly politely but correctly question the ability of the large UNESCO bureaucracy to “lead effectively the operational charge to protect cultural heritage in zones of armed conflict,” noting that UNESCO’s “catering to member states” actually hinders the protection of cultural heritage during wars. To the authors’ question “Is UNESCO not, in fact, impotent when what effective protection of cultural heritage necessitates is not consistent with what some governments have decided?” the answer from any reasonable observer must be a resounding “Yes!”

In this reader’s eyes, the UNESCO bureaucracy has shown itself incapable of thinking beyond the statist model or reconsidering its blind adherence to the idea that all art must always stay in its country of origin. Intentionally or not, UNESCO has discouraged the creation of safe havens – even after UNESCO pettifogging and delay with regard to the establishment of a Swiss safe-haven for Afghan antiquities resulted in the destruction of the objects in the Kabul Museum by Taliban wielding sledgehammers. UNESCO’s administration may believe its own rhetoric about states being the best protectors of heritage, but some of its oldest members – China, for one – have been among the worst offenders against minority groups within their own borders.

Chapter 2 of the paper concludes with a description of a new organization, ALIPH, founded by France and the UAE. ALIPH is working to create an international network of safe havens and will support “prevention training, implementation of emergency safeguarding plans, compiling inventories, [and] digitizing collections.” (p24) Many observers would agree that this kind of training will not only help to circumvent cultural heritage disasters, but will significantly disincentivize looting for profit, since a documented stolen object cannot be sold.

Ruins of the outer arcade of the Temple of Bel, Palmyra, Syria, 2005, now destroyed.

Chapter 3, “International Action to Protect Cultural Heritage: Key Debates,” examines the question of whether cultural heritage is important to all of us – or just to the people who live in the particular nation within whose contemporary boundaries art and artifacts were created.

The authors identify three major “political fault lines” that make it more difficult to establish a new international framework to protect cultural heritage. The first barrier is what they call the ‘sanctity’ of sovereignty. This absolutist perspective on sovereignty was questioned by Kofi Annan in the 1990s in the context of human rights abuses, when the then Secretary-General called on the United Nations to protect individual human beings rather than the governments who abuse them. Yet sovereignty is often equated with absolute control over cultural property, and the mantle of defender of cultural heritage is readily assumed by national governments.

This reader notes that there are many instances in which state governments which claim to protect their national heritage actually neglect archaeological resources and cultural institutions, using these claims primarily for political grandstanding or to cover domestic abuses of power.

Weiss and Connelly identify the second barrier to protecting cultural heritage as the rising power of non-state actors with whom the UN is reluctant to negotiate. Some nations see negotiation with these actors as tantamount to recognition. More often, the problem is that non-state actors cannot be held accountable except by military action, and military action is extremely difficult for the UN.

The authors find the third and most common problem is many nation states’ claims of absolute national ownership of cultural property and these states’ parallel denial of cultural property’s universal value and refutation of the global responsibility to protect it.

Chapter 3 discusses issues of ownership versus stewardship, nationalistic views versus cultural internationalism, and the political forces which have made nationalist approaches dominant over the last fifty years. These narrower approaches are compared to internationalist perspectives. The authors cite the position of the late John Henry Merryman as an alternative: “Rather than considering who has the strongest claim to an object, [Merryman] proposes three criteria to make a judgment about policy options: preservation, truth, and access. Which outcomes promote the best preservation of an object, the greatest scholarly utility, and the greatest degree of public and specialist access?”

This reader notes that in practical terms, national ownership claims, or claims that items were stolen from source countries, often cannot be resolved, because the circumstances and the legality of long ago transactions are unclear. Many museum and private acquisitions took place under different legal regimes, and artworks flooded to the West and North from countries where export laws, if they existed, existed only on paper and were not enforced. Source countries have delayed in making claims; some for 50-70 years or more. Other nations have claimed that although exports took place legally, they were lawful only under a legal system imposed by colonial oppressors, and therefore the export was immoral, if not illegal. Cultural property cases tend to be tried in the media, and the media is often ill-informed. None of this is conducive to finding fair and equitable solutions to restitution claims.

Despite these challenges, Weiss and Connelly suggest practical steps to overcome the barriers of 20th century nationalism, non-state and pariah actors, and move beyond blanket ownership claims. They focus on options involving stewardship and on developing working policies to protect cultural heritage.

Chapter 4, “The Politics of R2P,” outlines how R2P, the ‘responsibility-to-protect’ doctrine that allows international intervention to stop imminent war crimes or genocide, is also applicable to situations of destruction of cultural heritage.

The authors begin with a 2001 report discussing R2P by the Canada-sponsored International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS), and follow the concept’s evolution as a diplomatic and policy norm, tracking it through numerous NGO efforts to protect civilians and calls on the UN to authorize the use of force to prevent and react to atrocities. The R2P doctrine encouraged the UN’s 2011 Resolution 197, which called for the immediate cessation of state violence against civilian populations in Libya.

Weiss and Connelly show how the three-pronged concept of R2P – to prevent harm, to react, and to rebuild – led the ICISS to advocate proactiveness in crises. “The real goal for prevention… is to exhaust measures to “make it absolutely unnecessary to employ directly coercive measures against the state concerned.” (ICISS Report page 23)

The ICISS “precautionary principles” outlined by the authors include ensuring that the purpose of international actions are truly humanitarian in nature, that action is taken only as a last resort, by using only proportional means, not overkill, and that negative consequences do not outweigh benefits.

The ‘react’ component extends from sanctions to international criminal justice actions, and ultimately to military intervention in cases of large scale loss of life, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.

Despite criticism of ICISS’ proposals from different sides, the authors say that its “original three responsibilities provide the most logical starting point to fashion a workable conceptual framework for the protection of cultural heritage in armed conflicts.”

A U.S. Marine with a ground combat element assigned to Delta Company, 2nd Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion, walks through the Hatra Ruins in the Jazeerah Desert in Iraq on July 20, 2008. DoD photo by Lance Cpl. Albert F. Hunt, U.S. Marine Corps. (Released)

Finally, Weiss and Connelly set forth a draft framework to guide international action that begins with education, the expansion of a network of safe havens, the application of existing anti-looting legislation inside threatened countries, and systematic cataloging of all cultural heritage. The authors discuss the applicability of military force and the nascent growth of the Italy-based Blue Helmets of Culture, but find more positive results through developing relationships with local populations and working with civil society organizations.

As a next step in framing a cultural property policy based on the pillars of R2P, the authors suggest the creation of an independent international body, which is discussed in Chapter 5, “Assembling a Commission?” This section discusses steps already taken by the UN, by various conferences focusing on cultural heritage, and UNESCO’s Emergency Task Force on Cultural Heritage.

(A serious question, only lightly touched on in the article, is whether these various international groupings will ever step beyond their deference to states’ goals rather than international ones, or get past the current, erroneous and distracting focus on alleged terrorist funding through looting of cultural property.)

The authors note that regional balance and diversity will be essential to developing solid cultural heritage policies, but note that source countries include the wealthiest and poorest nations in the world community.

This reader thinks that part of the challenge will be to learn from international constituencies not often heard in such international fora, such as art dealer organizations, auction houses, and other experts on art, and to include museum administrators from every region. It is also more useful to hear from boots-on-the-ground defenders of threatened heritage in countries in crises than government flunkies, and to include minority and indigenous voices from developing countries.

Weiss and Connelly say the moment seems propitious for developing an independent international commission, with an agenda covering issues from best practices on heritage protection to cataloging all objects, to facilitating International Criminal Court prosecutions for those who attack cultural heritage under international law. Prospective members of such an international body would do well to read Cultural Cleansing and Mass Atrocities: Protecting Cultural Heritage in Armed Conflict Zones, as a start.

Theater Sabratha, Libya. By SashaCoachman (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

Theater Sabratha, Libya. By SashaCoachman (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons