Lichens threaten most important Iranian heritage sites

Persepolis, Achaemenid Soldiers relief showing lichen infestation.

Conservation experts are sounding the alarm over imminent threats to ancient Iranian heritage, sparked by concerns over damage by lichens to the inscriptions and relief sculpture on the walls of Persepolis. Lichens are a complex life form that are a symbiotic partnership of two separate organisms, a fungus and an alga. Lichens excrete various organic acids, particularly oxalic acid, which can effectively dissolve minerals; they have affected stone surfaces more than 1.5 centimeters deep at Persepolis.

The lichen infestation at Persepolis is attributed to a mix of acid rain and changing local climate. Depletion of groundwater in the region has caused the land around Persepolis to sink by as much as 600 meters in some areas. The immediate public concern was heightened by information provided recently by Iran’s Deputy Minister of Cultural Heritage regarding the country’s lack of funds for maintaining crucial sites. Despite the increasing importance of world heritage tourism and the building of a new international airport near Persepolis, Deputy Minister Ali Darabi revealed that Iran’s budget for restoring historical sites and monuments was incredibly small, at 900,000 Iranian rials ($200) and 13 million rials ($3,000) respectively. (Rates were as reported in Iran, bank rates are far more unfavorable.) Iran has 27 UNESCO World Heritage sites, among the highest number in countries globally. By comparison, Italy allocated €800 million and Germany €647 million for cultural heritage preservation in recent years.

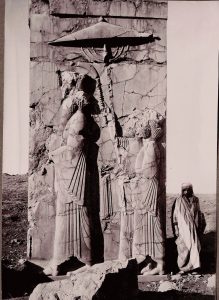

Persepolis, early 20th century, private collection

Following Darabi’s remarks, experts have underscored long-standing mismanagement issues endangering historical monuments, particularly at Persepolis, the ancient heart of the Achaemenid Empire. Specialists have aimed criticism at the National Heritage Department for failing to safeguard the site.

Former Persepolis conservation head Maziar Kazemi emphasized lichens’ destructive impact on historical sites, when conservation work is not regularly undertaken. He noted both Iran’s inadequate budget allocations and the difficulty of obtaining visas for international collaborations. Kazemi highlighted a past joint project with Italian experts to treat lichens, now abandoned due to budget constraints and bureaucratic hurdles. Japan has also sent conservation and archaeological specialists to assist at Persepolis.

Cuneiform inscriptions are also at risk from damage by lichens and fungus infestation, particularly in Behistun, another major Achaemenid site.

Alireza Askari-Chaverdi, the site’s director, has said that ongoing research and field investigations at Persepolis continue, but there continue to be challenges to finding effective treatments due to lichen’s diverse nature. Treatments that work on some lichens do not work on others. The Sivand dam on the Polvar River between Persepolis and Pasargadae appears to have caused increasing humidity around the two sites since its construction in 2007, which has exacerbated the growth of lichens. Continued erosion due to wind and sand also requires serious attention. Studies have been undertaken detailing the extreme need for preservation at Persepolis by replacing surface mortars but restoration work has not been implemented.

Persepolis, floret showing lichen infestation.

Given the complete lack of available funding in Iran, collaboration with international experts is crucial: Askari-Chaverdi also emphasized the need for studies to develop more effective preservation methods and to address the problem soon, as important relief sculptures at the site are crumbling.

Preservation at Giza: Menkaure pyramid cladding plan abandoned

The January 2024 restoration plan for the Menkaure pyramid, one of the three great pyramids at Giza, has been abandoned completely. Menkaure’s pyramid, unique among the Giza pyramids for being originally clad in granite rather than limestone, had only a few layers of granite installed before construction ceased thousands of years ago. The initial proposal had been hailed a few months ago as the “project of the century” by Mostafa Waziri, secretary general of the supreme council of antiquities. Originally, the plan was to replace the crumbling facade of the pyramid with existing stone scattered around the the site (as well as possible new layers of granite sheathing). The proposal entailed detailed scanning of all the granite stones now remaining at the site in order to determine their original placement. The decision not to complete the project was announced in by a committee formed under Egypt’s tourism minister.

However, it was met with intense domestic and international backlash due to concerns about altering the ancient monument. Archaeologist Monica Hanna pointed out that the stones currently on the site had been proven not to have been used on the pyramid by the ancient Egyptians, as was proved in the work of American Egyptologist George Andrew Reisner in the nineteenth century.

South West corner of Menkaure’s Pyramid, 7 July 2007, photo Jon Bodsworth, copyright free.

A review committee, led by former antiquities minister Zahi Hawass, unanimously opposed the reinstallation, citing concerns about preservation and the inability to accurately reconstruct the original layout. Additionally, the committee tentatively approved excavating the pyramid’s boat pits after a comprehensive scientific study. In light of the ill-considered decision to replace the original but now crumbled and displaced granite, Hawass made emphatically clear the need for better research before ‘remaking’ or taking on any other irreversible projects at the pyramids of Giza.

Persepolis Relief, showing damage and lichen infestation, 18 May 2015, photo by Pawel Ryszawa, 3.0 Unported license.

Persepolis Relief, showing damage and lichen infestation, 18 May 2015, photo by Pawel Ryszawa, 3.0 Unported license.