In mid-October, Bertrand Guillet, Director of the Chateau des Ducs de Bretagne’s Musée d’Histoire de Nantes announced that the museum was making an ethical decision to postpone a long-planned exhibit on Genghis Khan. Fils du Ciel et des Steppes: Gengis Khan et la naissance de l’Empire mongol (Son of Heaven and Steppes: Genghis Khan and the birth of the Mongol Empire), was originally developed in partnership with the Inner Mongolia Museum in Hohhot, China, a museum dedicated to the history of the Mongolian steppes, including the life of Genghis Khan and the Mongols. The Nantes museum will replace the loaned objects from China with items from French and international museum collections.

Mongol riders with prisoners. The prisoners are presumably robbers and similar criminals. Illustration of Rashid-ad-Din’s Gami’ at-tawarih. Dschingis Khan und seine Erben (exhibition catalogue), München 2005, p. 254, Public Domain.

The 13th century warrior Genghis Khan was the founder of the Mongol Empire, the largest contiguous empire in world history. In their brutal beginnings, Genghis Khan’s Mongol troops joined with Turkic warriors to sweep from Mongolia across Central Asia, overcoming Muslim rulers and destroying cities from Balkh to the Baghdad Caliphate. At their height, the Mongols conquered all of China, Central Asia, much of the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and large swaths of what would become Russia. In China itself, Genghis’ descendant Kublai Khan created the Yuan Dynasty, which maintained control for nearly one hundred years, until 1368.

The once ruthless Mongol steppe warriors were later renowned for their sophisticated diplomacy,

Genghis Khan Mausoleum near Ordos in Inner Mongolia, Author Samxli , 6 June 2008, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

their patronage of the arts and sciences, and for their religious tolerance. One of the great achievements of Genghis Khan and his descendants was the creation of the political, trade and administrative system linking much of the Mongol kingdoms, which came to be known as the Pax Mongolica. The resulting security and benefits to trade were remarkably effective: according to Juvaini’s Tārīkh-e jehān-goshāy (“History of the World Conqueror”) (begun in 1252-1253):

“For fear of his yasa and punishment his followers were so well disciplined that during his reign no traveler, so long as he was near his army, had need of guard or patrol on any stretch of road ; and, as is said by way of hyperbole, a woman with a golden vessel on her head might walk alone without fear or dread.”

Exhibition censorship and the rewriting of Mongol history

The Nantes exhibition, Fils du Ciel et des Steppes: Gengis Khan et la naissance de l’Empire mongol, already delayed by the coronavirus pandemic, will now be put off until 2024. The reason for this new postponement is not the pandemic but censorship by the Chinese government, which Guillet describes as “the hardening of the Chinese government’s stance this summer against the Mongolian minority.” Said Guillet:

“We decided to stop this production in the name of the human, scientific and ethical values that we defend.”

The Catalan Atlas, drawn in 1375 by Cresques Abraham in Majorca and currently in the Bibliothèque nationale de France

The Musée d’Histoire de Nantes’ stand against censorship was taken after blatant demands by China to completely change the story told by its exhibition. First, the Chinese Bureau of Cultural Heritage issued an injunction to the museum to remove the words “Genghis Khan”, “Empire” and “Mongol” from the exhibition. As the exhibition is about Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire, this came as a shock to the French museum.

Then, at the end of the summer, the Beijing heritage office went further, modifying the proposed content of the exhibition and requesting full control of the explanatory texts, maps, catalog, and exhibition-related communications.

According to the Musée d’Histoire de Nantes, “The proposed new synopsis, written by the Beijing heritage office, applied a censorship to the initial project that includes… biased rewriting aimed at making Mongolian history and culture completely disappear for the benefit of a new national story,” a rewritten history casting the Mongol achievements as Han Chinese.

In preparation for their new planned opening date in 2024, the museum is arranging for loaned objects with other museums in Europe and the U.S. for a re-designed, uncensored exhibition narrating the history of Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire that the Chinese government wanted erased.

Disney succumbs to Chinese pressure in Mulan

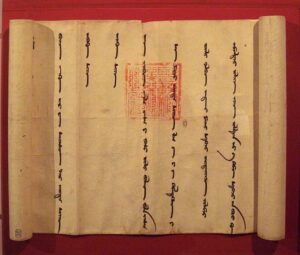

Letter from Mongolian ruler Oljeitu to King of France Philippe le Bel, in 1305. (PHGCOM/CC BY SA 4.0)

This isn’t the first time this year that China has dictated or attempted to dictate a cultural narrative. Hollywood has also been pressured to produce popular films that re-work history. Many see the shadow of Chinese governmental policy in Disney’s adaptation of Mulan (2020), in which Mulan (Liu Yifei) fights alongside an ethnically-Chinese army to defend the Han Emperor from merciless (and Muslim-coded) invaders. The invading army is led by “Böri Khan” (Jason Scott Lee), and hails from a geographic area which overlaps with modern Xinjiang. The film was widely criticized outside China for its promulgation of what many saw as Chinese government propaganda, for its lead actress’s endorsement of police brutality in Hong Kong, and for a note in the credits thanking the government’s publicity department of Xinjiang, where scenes from the movie were actually filmed. The fact was forgotten that in the original story – on which both this film and Disney’s 1998 animated version were based – Mulan is fighting on behalf of a China that was, at that time, led by a Mongol Khan. Disney is said to be deeply embarrassed that it appears to be condoning the persecution of the Uyghur population – but the bottom line is that China is one of Hollywood’s biggest markets.

China’s official policy is to define minority religious and family culture as a ‘sickness’

Entrance of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Museum in Ürümqi, with a banner saying “Under the guidance of Xi Jinping’s ideology of socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era, we strive to compose the Xinjiang chapter of the Chinese nation’s great rejuvenation of the Chinese dream.” In the middle, there is a display of Xi Jinping, accompanied with the caption “General Secretary Xi Jinping and people of all ethnic groups in Xinjiang are united in mind.” Author Kubilayaxun, 26 August 2018, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

China’s President Xi Jinping has promoted ‘ethnic unity’ rooted in Han Chinese cultural identity as a matter of policy. At a gathering in September 2019 to “honor national role models for ethnic unity and progress” he stated, “Only the Chinese Communist Party can achieve the great unity of the Chinese nation, and only socialism with Chinese characteristics can unite and develop all ethnic groups and make them prosper.”

For Mongolians within China, the denial of Mongolian history and identity raises fears of forced assimilation. Protests in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, an area within China but with partial independence from the central government, began at the end of August 2020 in response to curriculum changes that replaced Mongolian language instruction and text books with Mandarin substitutes, a move that many ethnic Mongolians saw as an attack on Mongolian culture. Chinese law guarantees all children the right to an education in their native language. There were school boycotts and protests for weeks in response to the new requirements, but the central government’s position only hardened. Many fear that the central government will start to impose severe repressive measures like those suffered by Muslim minorities in China’s Xinjiang province.

The Tibet Autonomous Region has not been spared either. In January 2020, the People’s Congress of Tibet passed “Regulations on the Establishment of a Model Area for Ethnic Unity and Progress in the Tibet Autonomous Region.” Also known as the Ethnic Unity Law, this legislation was implemented in May 2020. As translated by the Unrepresented Nations & Peoples Organization (UNPO), Art. 3 of the legislation states that “safeguarding oneness of the motherland, strengthening ethnic unity, and taking an unambiguous stand against separatism are common responsibilities of all people from all ethnic groups.” Many Tibetans are worried about how much room this leaves for a truly Tibetan culture in China.

The most horrific abuses are happening in Xinjiang province

Rights organizations around the world have condemned China for its brutal abuse of human, cultural, and religious rights in China’s westernmost province, the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, where over one million Uyghurs have been detained in so-called “reeducation camps” that are designed to erase their cultural identities. These “re-education camps” are actually concentration camps with guard towers and razor-wired high walls. Hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs – some say up to 2 million – are imprisoned in them under dire conditions. Participating in family, communal and religious traditions are not only crimes warranting an indefinite sentence, they are considered an ‘illness’ to be ‘cured’ by incarceration and forced adoption of ‘better’ Han Chinese ways. Men, women and teenagers who resist are starved, beaten, raped, and killed.

Three wax statues at the “Ethnic Minorities Exhibit” at the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Museum in Ürümqi. One of the statues is supposed to represent a Uyghur man grilling kebabs; the statue next to him is of a female tourist posing next to him while making a peace sign, and standing opposite these two statues is another one of a male tourist taking a photo. Author Kubilayaxun, 26 August 2018, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The hundreds of concentration camps scattered throughout Xinjiang have been ‘updated’ for the 21st century – combined with forced labor factories where prisoners churn out textiles and consumer goods for the world market. Because being Uyghur is enough to justify imprisonment, whole villages have disappeared into the camps. Hundreds of thousands of young children, orphaned or forcibly separated from their families have been sent to prison-like school camps where they indoctrinated against Uyghur culture, while Uyghurs who have not been detained are subject to extreme surveillance, including by having Chinese soldiers living in their homes for weeks at a time in order to ensure that they have no anti-state sympathies. Uyghurs are prevented from virtually all religious observance and can be arrested for such minor acts as abstaining from alcohol or growing a beard.

Highly educated, prominent Uyghurs, including many former officials, University administrators and professors who have succeeded within Chinese society are equally or more at risk than humble villagers and workers. Since 2016, hundreds of Xinjiang’s most prominent intellectuals, authors, educators, authors, poets, and musicians have disappeared into the camps and not returned.

The art world’s half-hearted responses

Uyghurs and supporters demonstrate in Berlin for the human rights of persecuted Muslim minorities in China, following the July 2009 Ürümqi riots, Claudia Himmelreich, 10 July 2009, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

China’s treatment of the Uyghurs has inspired some art world figures to criticize European and American art museums’ collaborations with their Chinese counterparts as well as directly with the Chinese government. In an interview with The Art Newspaper, exiled Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei accused foreign art museums that participate in exchanges of abetting China’s “crude censorship on ideology and free speech,” and saying, “they perform their role well.”

The Art Newspaper has reported on how lucrative these projects can be for the Western museums, which often take the form of blockbuster loan exhibitions to Chinese museums. In their public responses, the Tate, the Victoria & Albert Museum, and the Centre Pompidou have all attempted to frame their work in China as a positive form of cultural exchange, fostering mutual understanding – and as necessary sources for funding for arts institutions suffering from the financial shortfalls caused by this year’s shutdowns.

The decision by the Musée d’Histoire de Nantes to reject China’s censorship goes against this current of capitulation, in which European museums are willing to ignore cultural repression in Xinjiang while touting how much exhibitions and exchanges are doing to promote freedom of thought in China. China’s demands to the Nantes museum were so egregious, however, that its story may give other museums pause.

What can museums do?

Kublai Khan and His Empress Enthroned, from a Jami al-Twarikh (or Chingiznama), India, 1596, Kesu Kalan Mughal dynasty Akbar(r. 1556 – 1605), Freer Gallery, Smithsonian Asian Art Museum.

As an economic, political, military, and cultural heavyweight, China cannot be ignored by the world’s governments, and its powerful influence and deep pockets have been useful to museums and arts promoters in many countries. Many have questioned whether the abhorrent politics espoused by the Chinese government are sufficient cause to boycott Chinese cultural products, historical or contemporary, or to threaten the Chinese people’s access to foreign arts and culture.

But in light of the blatant assaults on history, on multiculturalism, and on the rights of minorities, neither can foreign museums blithely volunteer themselves for partnerships with Chinese cultural institutions or go along with government initiatives that require abandoning principles of free expression and trading the facts for the propaganda goals of a dictatorship, no matter how lucrative.

Arts institutions ought to hold themselves to a higher standard than the tech companies who sell security technology to China or investment bankers reaping profits from forced labor. If museums are to continue to pursue collaborations with China, they should make clear, to themselves and to their audience, what the stakes are and where the line is drawn. They must not accept censorship of their exhibitions, and they must not be complicit in the distortion of their narrative, whether at home or in Chinese territory. As stewards of history, and of culture, maintaining these principles is worth more than any partnership, foreign or domestic.

Emperor Taizu of Yuan, personal name Temujin, better known as Genghis Khan. Page from an album depicting several Yuan emperors (Yuandai di banshenxiang), now located in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Paint and ink on silk.

Emperor Taizu of Yuan, personal name Temujin, better known as Genghis Khan. Page from an album depicting several Yuan emperors (Yuandai di banshenxiang), now located in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Paint and ink on silk.