Copy of Igbo-Ukwu bronze; rendering from the 3D model of the Roped Pot © Factum Foundation.

The Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation, headed by Adam Lowe, has long been a leader in the digital preservation of cultural heritage – and in building collaborative projects with institutions and communities. Through its Selene Project, Factum Foundation is transforming how institutions study and share cultural artifacts in Europe, Africa and the Middle East. In the process, they are training a new generation of digital ‘preservationists.’ Factum’s collaborative programs – ARCHiVe, ARCHiOx, and Colnaghi x Factum – are breaking new ground, with online and in-person training on digital preservation techniques, emphasizing precision and innovation in recording cultural artifacts.

Most of Factum Foundation’s current digitizing projects involve well-known Western institutions and famous collections. One project, in Nigeria, highlights a lesser-known aspect of the global repatriation debate—ensuring local access to cultural heritage claimed by national governments.

The Igbo-Ukwu bronzes, dating back to the 9th century AD, testify to the sophisticated craftsmanship of an ancient bronze metal-working culture in southeastern Nigeria. Despite their historical significance, none of the original Igbo-Ukwu bronzes are in Igbo-Ukwu itself. Requests by the community for access to the artifacts held at the National Museum in Lagos have been declined due to security concerns. Frustration within the Igbo-Ukwu community over inability to share its local artistic heritage with its younger members and visitors gave impetus to the digitization project.

The Factum Foundation, together with the Igbo-Ukwu community, Dr. Pamela Smith, and Dr. Kingsley Daraojimba, launched a project to digitize the known bronze artifacts. As part of the project, community members are learning advanced photogrammetry techniques under the guidance of Factum Foundation experts.

The bronzes recorded during the training sessions are being transformed into high-resolution 3D models. Eventually, these will be 3D printed and cast in bronze using the ceramic shell centrifugal casting method, which ensures accurate replication of the fine surface details. Once complete, these replicas will be displayed at the Shaw Institute of Cultural Art (SICA), in Igbo-Ukwu.

Imran Khan teaching photogrammetry to Igbo-Ukwu community members, © Ferdinand Saumarez Smith, Factum Foundation.

The story of the Igbo-Ukwu bronzes began in 1938 when Isaiah Anozie, a local villager, unearthed the first artifacts while digging a cistern near his home. This accidental discovery led to the formal excavation of the site, later known as Igbo Isaiah, by archaeologist Thurstan Shaw in 1959, at the request of the Nigerian government. Subsequent excavations in the 1960s by the Ibadan Institute of African Studies uncovered two additional sites: Igbo Richard, a burial chamber, and Igbo Jonah, a cache of artifacts.

Artifacts from these sites include bronze, copper, and iron objects, jewelry, ceramics, and regalia, some of which contain materials linked to long-distance trade networks extending to Egypt. Five notable pieces from the original excavation—such as a crescent-shaped vessel and a chief’s head pendant—are now housed in the British Museum, while others reside in the National Museum in Lagos and the University of Ibadan. Radiocarbon dating places the artifacts to approximately 850 AD, making them the earliest known examples of bronze casting in the region.

Igbo-Ukwu, historically known as Igbo-Nkwo, was the capital of the Kingdom of Nri during the 8th or 9th century AD. It served as a key hub in a trade network extending to Gao in present-day Mali and further to Egypt and North Africa. The artifacts reveal a society with a complex religious system, agricultural economy, and long-distance trade connections.

Among the artifacts, intricate designs and techniques demonstrate the advanced skills of the Igbo-Ukwu artisans, particularly in lost-wax casting—a method predating similar practices in other parts of Africa.

3D print in stainless steel of the Igbo-Ukwu Bronze Shell, © Oak Taylor-Smith | Factum Foundation.

The Igbo-Ukwu bronzes not only illuminate the advanced technological and artistic achievements of the Igbo-Ukwu people but also serve as a reminder of the enduring need for equitable access to cultural heritage. By combining modern technology with collaborative efforts, the Factum Foundation and its partners are helping to restore a sense of ownership and pride in this remarkable legacy, ensuring that the story of Igbo-Ukwu continues to inspire future generations.

2024 and 2025 Projects at Factum Foundation

Other 2024 and 2025 projects at Factum Foundation are working with the Selene Photometric Stereo System (PSS), which captures surface details of cultural artifacts in unprecedentedly high resolution to digitize collections and make them accessible to researchers, educators, and the public.

In collaboration with the Universidad de Zaragoza, the Foundation led an intensive seminar on the 3D digitization of the Oratory in the Aljafería Palace, an 11th-century Islamic structure. Using high-resolution photogrammetry, students captured intricate plasterwork details, honing their skills in real-world applications. In January 2025, the Universidad de Granada will work with Factum experts to record the yeserías (stucco carvings) in La Madraza Palace, a landmark of Nasrid architecture.

In July 2024, Factum Foundation installed a Selene PSS in the Study Room in the Department of the Middle East at the British Museum. This system will digitize over 130,000 cuneiform tablets, revealing the smallest details of inscriptions, cylinder seal impressions, and even fingerprints left by ancient artisans. The project will be led by curators Dr. Jon Taylor and Dr. Mathilde Touillon-Ricci.

The Selene PSS installed at the Instituto Valencia de Don Juan © Factum Foundation.

The Princeton University Library is leveraging the Selene system to explore its collections, from ancient cuneiform tablets to Renaissance engravings. Recent achievements include revealing hidden watermarks on Islamic manuscripts, identifying areas of repair in an Albrecht Dürer engraving, and analyzing gilded surfaces on a 1455 Horace manuscript.

With support from The Helen Hamlyn Trust, a Selene PSS was installed at the Instituto Valencia de Don Juan in Madrid, home to one of the world’s most significant collections of Andalusian art. The system has already captured the surface details of antique embroideries and Hispano-Arab ceramics in 2.5D. This collaboration includes plans to digitize objects for the 2025 Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

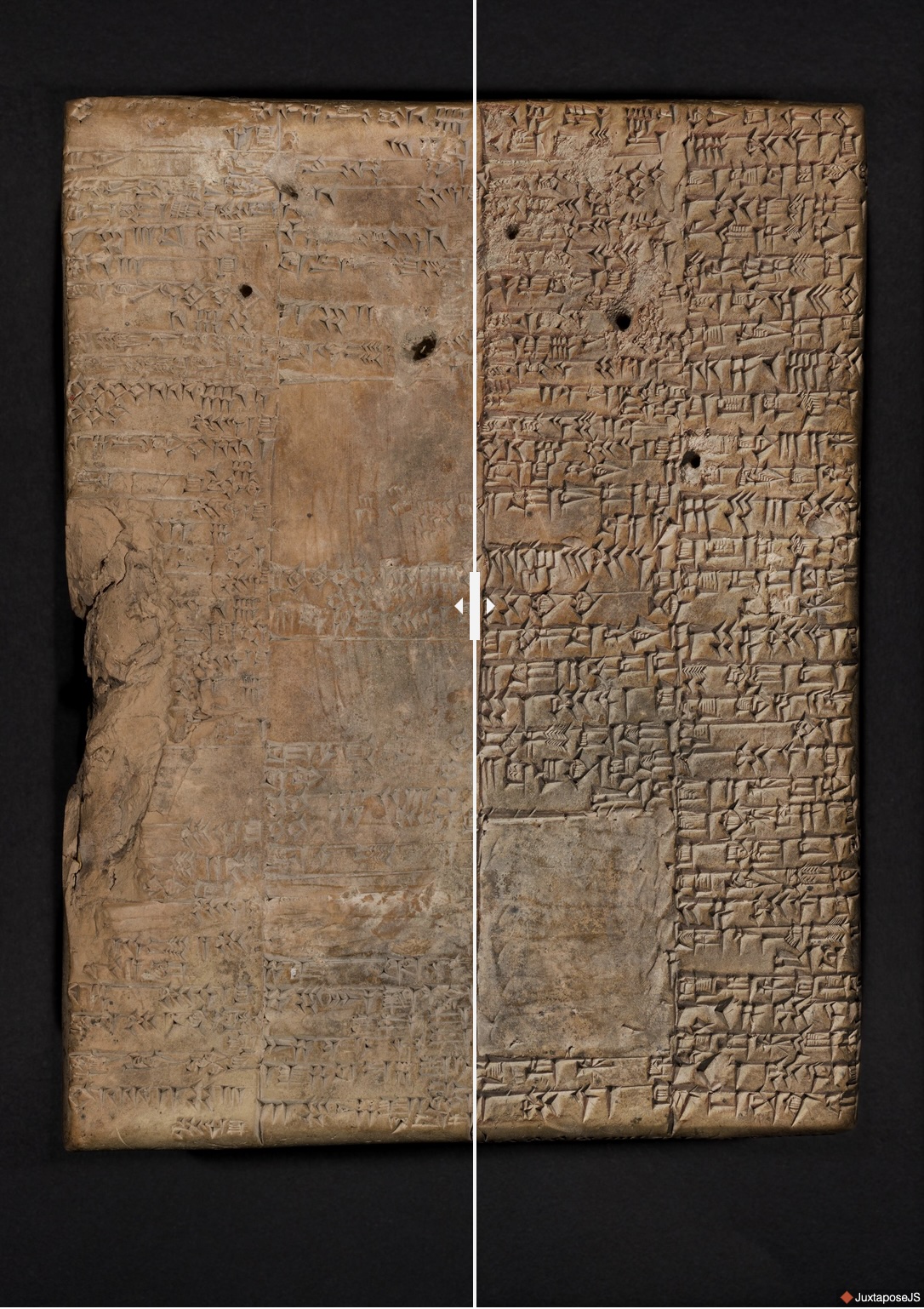

Composite image of a cuneiform tablet showing standard photography at left and Selene capture on right, showing how Selene system has captured the topography of the tablet and stylus marks as never before, allowing researchers a more detailed view of what was written and the tool markings, thanks to the generation of a depthmap of the surface and a composite image from the outputs. Courtesy Factum Foundation and Princeton University Library.

Composite image of a cuneiform tablet showing standard photography at left and Selene capture on right, showing how Selene system has captured the topography of the tablet and stylus marks as never before, allowing researchers a more detailed view of what was written and the tool markings, thanks to the generation of a depthmap of the surface and a composite image from the outputs. Courtesy Factum Foundation and Princeton University Library.