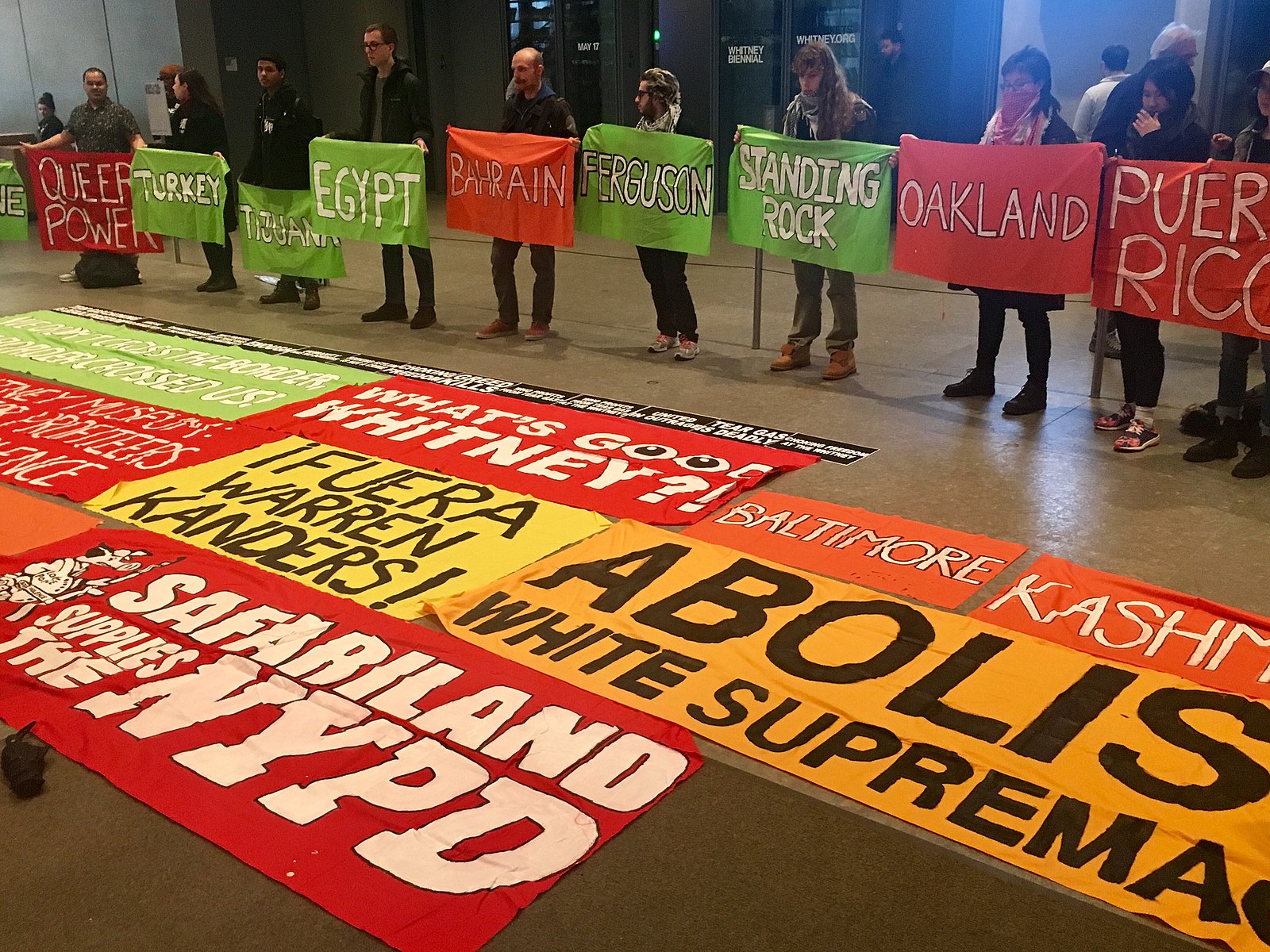

In a recent longform article for The Art Newspaper, Barbara Pollack highlighted the extraordinary rise in public protests taking place at America’s leading art museums. These are not reactions to polemical new artists, or even a revival of the playful ‘Renoir Sucks’ protests of yesteryear. In most cases, the art and artifacts on display in these museums were entirely tangential to the protesters’ ire. The protesters’ grievances with the museums vary, from contributing to gentrification to accepting donations from the Sackler family, a branch of which is heavily implicated in the American opioid crisis. The targeted museums have not just been passive sites for protest; some museum staffers have added their own voices to the outcry. The clearest case of this participation took place at the Whitney Biennial, at which protesters gathered repeatedly to call for the removal of Warren B. Kanders’ from the museum’s board. Members of the Whitney staff, as well as the majority of artists showing at the Biennial, have joined in the call for Kanders’ removal. Several of the public protests took place during an exhibition that featured artwork highlighting crowd-suppression by security forces using tear-gas canisters manufactured by a subsidiary of Kanders’ own Safariland Group.

The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, photo by MusikAnimal, Wikimedia Commons.

The Whitney is not the only art museum using its public platform to combat ongoing perceived political and social injustices. Apart from providing a venue for protest, many museums are looking inward, seeking ways to reform their collections, programming, and staff, to better serve a diverse (and outspoken) audience. Modern art museums in particular are now deliberately adding works by non-male and non-white artists to their permanent collections and temporary shows.

In parallel with the wide range of exhibitions of art by a diverse cast of contemporary artists, historical museums in major cities are increasingly pursuing programs celebrating the history of world art and indigenous cultures. The British Museum currently features an exhibition, Reimagining Captain Cook: Pacific Perspectives, which pairs artifacts collected by Cook on his exploratory voyages with artwork by contemporary Pacific artists reflecting on their history. The exhibition was planned to coincide with the 250th anniversary of Cook’s voyage but focuses not on the experiences of the British explorers but on the long-term effects of their reports on perceptions of the Pacific Islanders. The legacy of Cook’s voyage and the traditional role he has been given in Australia as “discoverer of the continent” is the subject of polarizing debate there. Cook’s methods of acquiring some of the exceptionally rare objects in the exhibition are also controversial and raise broader questions about where and by whom such objects should be held, among them a Tahitian formal costume which he collected, one of very few still in existence.

Burlington House, Royal Academy of the Arts, London, February 2014, photo by Bengt Oberger.

Putting on exhibitions of art and artifacts from across the world is nothing new for Western art museums, but what has changed is the attitude taken by the host institutions to the artworks on display. Increasingly, there are attempts to acknowledge the artworks as part of a living tradition, and recognize them as the heritage of peoples who are among the intended beneficiaries of the show. During their recent Oceania exhibition, the Royal Academy offered all citizens of New Zealand and Pacific Islanders free admission, while a notice on the main exhibition page informed all visitors of the cultural importance and sensitivity of the artifacts on display: ‘This exhibition includes many objects that Pacific Islanders consider living treasures. Some may pay their respects and make offerings through the duration of the exhibition.”

Public displays of sacred (and secular) cultural property from indigenous groups are never uncontroversial or universally accepted, but the Oceania exhibition received strong positive responses from British and Islander reviewers alike, and was welcomed by members of the Pacific community. Pacific Islanders were invited to bless the exhibition spaces before they opened, in a ceremony which included dancers in traditional dress progressing through the London street and into the RA’s gallery space.

These new exhibitions of art and material culture from specific ethnic or cultural groups are also increasingly curated by representatives of those groups. This has become a priority, to the degree that curator Brian Just of the Art Institute of Chicago recently made the determination to postpone an exhibition of Mimbres pottery until a Native co-curator for the show was given a consultative role.

The British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and similar institutions are better able to pursue a more diverse exhibition program than smaller regional museums. These major institutions have long-established collections of historical art and artifacts from across the globe – another reason why they are criticized for ‘hoarding’- but their vast resources are what enables them to build comprehensive exhibitions in the first place. Any voids in their collections can be temporarily supplied through loans facilitated by their prestigious reputations and their long-established relationships with fellow museums and private collectors. For less well-endowed ethnographic and art historical museums, diversifying their collections is an even greater challenge than diversifying their staff. Museum-quality objects are simply harder to attain, and public attention and private funds are more often directed to contemporary art than to historic collections.

Even so, older artworks continue to play a powerful role in contemporary political discourse. The impact that museums of art and culture will have in future depends greatly upon who has access to historic artworks, and what facilities museums have to educate their publics about the achievements of all cultures, not just Western traditions.

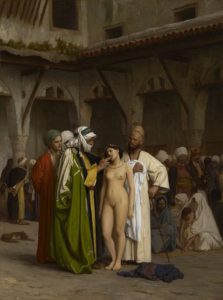

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Slave Market, c. 1866, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts

Berlin recently witnessed a poignant illustration of the power of art, and the importance of museum’s political attitudes towards their own collections and how they are displayed. In April 2019, the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, discovered that images of one of their artworks, Slave Market, by French Orientalist painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, had been appropriated for use in an anti-immigration campaign by the far-right party Alternative for Germany. The AfD, as it is known, is the third largest political group in Germany, having risen to prominence since its founding six years ago on a platform which includes a hardline anti-immigration stance. In recent years, the party and its members have been charged with racism, anti-feminism, homophobia, xenophobia, antisemitism, and Islamophobia. The aptness of Gérôme’s painting for appropriation by an organization hoping to promote fear and distrust of Syrian, North African, and Turkish migrants in Germany is undeniable. Slave Market depicts a light-skinned, nude woman, surrounded by three darker-skinned men in Ottoman dress, one of whom has inserted his fingers into her mouth, to check the condition of her teeth. Gérome’s work, as art historian Linda Nochlin has observed, projects European sexual fantasies and racial stereotypes onto a depiction of the Middle Eastern slave trade whose accuracy is, at best, dubious.

Unwilling to have their art collection politicized in this way, the Clark immediately submitted a letter to the AfD, calling on the party to cease all use of the image for its public campaign. Despite the Clark’s protest, the AfD has declined to take down any of their posters and will continue to use Gérôme’s painting to promote their views on immigration. Unfortunately, as Oliver Meslay, director of the museum, has stated, they have no options for controlling the use of the painting’s image “other than to appeal to civility on the part of the AfD Berlin.” Bereft of the power to prevent similar distorting appropriations of art, both long-past and recent, museums can fight back only by doing what they have always done: help their visitors better understand the histories of their own and other cultures, through the display of art and artifacts.

The very same international immigration, which the AfD and like-minded right-wing parties in Europe and America oppose, has contributed to the multiculturalism of modern cities across Europe and America. These diverse populations are being served by local art and history museums who are coming to recognize their responsibility to tell the stories and celebrate the heritages of all their communities. This is not just an obligation but an opportunity – a museum that speaks to a wider audience will have more visitors and higher visibility, leading to more vocal public support, donations, loans, and funding. Yet smaller regional museums, and museums in countries without a colonial history, are all at a disadvantage when attempting to develop collections of cultural artifacts that reflect the ethnic and cultural makeup of their 21st century communities.

In today’s increasingly restricted and polemical art market, these institutions will find it difficult to expand their holdings to reflect new goals for diversity. Relentless public scrutiny makes the acquisition of any kind of foreign cultural property very risky for museums, even in cases involving legitimately excavated artifacts or legally purchased antiques that left their source countries long before national-ownership laws were enacted. Museums are public institutions, and dependent on popular goodwill for the patronage that keeps them alive. Newspapers hungry for content to fill the twenty-four-hour news cycle, and the constant, critical conversation on social media, have made museums wary of controversy of any kind. Meanwhile, memoranda of understanding and blanket export bans dash the collection-building dreams of diversity-conscious curators.

If the museums of the future are to fulfill their function as educational institutions and as shared spaces that represent the backgrounds and heritage of all their community members, a new system for the circulation of art needs to be put into place. Perhaps artworks need to be issued with passports of their own, so that cultural property can retain its ties to its homeland while traveling around the world, just as people do.

(For other CPN reports on museum-targeted protests, see also Visual Politics – Protests and the Art Museum, Cultural Property News, March 30, 2018.)

A gathering of protestors at the lobby of the Whitney Museum, New York, NY, on April 5, 2019, the third in a series of events leading up to the 2019 Whitney Biennial, organized to demand that the museum remove Warren Kanders from the museum Board because of his role as owner of weapons manufacturer Safariland. by Perimeander, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

A gathering of protestors at the lobby of the Whitney Museum, New York, NY, on April 5, 2019, the third in a series of events leading up to the 2019 Whitney Biennial, organized to demand that the museum remove Warren Kanders from the museum Board because of his role as owner of weapons manufacturer Safariland. by Perimeander, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en