Vatican Canon’s Art Collection Comes Under Investigation… Again

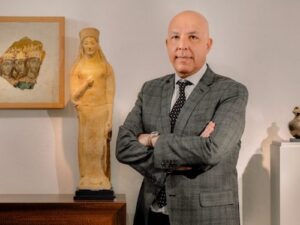

Don Michele Basso, the Vatican.

Scandal continues to dog the art collection of Vatican cleric Michele Basso, even after the elderly Monsignor’s death in January 2023. Described by supporters as a humble, gentle man and known as a passionate amateur archaeologist who participated in digs at the Vatican, he also possessed an extraordinary collection of artworks. Until he gifted his collection in 2022 to a Vatican-associated institution, the Fabbrica di San Pietro, Monsignor Basso is said to have possessed some seventy artworks. The collection was said to include Italian Baroque paintings by Guercino, Giambologna or their ateliers, a work by the school of Mattia Preti, sketches by Pietro de Cortona, and a 16th century bust of the young St. John the Baptist from the school of Michelangelo. These works are all now in the hands of the Fabbrica di San Pietro, an institution charged with maintaining St. Peter’s Basilica.

Monsignor Basso came from very humble origins; his mother was a caretaker and the family lived in poverty. Since he had no wealthy background, questions have been raised for years about how he acquired his many artworks, estimated at millions of dollars in value. In 2000, Basso was investigated by the Rome court for selling fraudulent artworks and avoiding export laws in a case that was eventually dropped. At the time, Basso’s lawyer said they were gifted to the Monsignor “by fellow clergymen and elderly noblewomen to whom he acted as spiritual adviser.” In an interview with journalist Franca Giansoldati in 2021, Basso again said he was given the artworks by “generous people.” “It’s like finding yourself with so many shoes in the closet. Some were bought and others were given away,” he said.

Example of a study by Pietro da Cortona, 1650, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Public domain.

Access to Basso’s collection could effect the legal status of a world-famous artwork

One of Basso’s best-known artworks is a copy of the famous Euphronios krater dating to 515 BCE, considered one of the greatest works of Greek art. The Basso copy is said to have been made in the 19th or early 20th century, when replicas of exemplary ancient vases and artworks were popular decorative objects and skilled fakers abounded. The date the copy was made has bearing on Italy’s claims to the true Euphronios krater, which was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1972. The krater was returned by the Met to Italy in 2008 after the Italian government alleged that it was illegally exported after being excavated by tomb robbers in 1971, and that its discovery was long after passage of Italy’s 1909 law banning export of antiquities. However, if Basso’s copy was actually made prior to the law’s passage and long before the original was said to have been found, it could raise questions about the case made by the Italian government. Alternately, Basso’s copy could be of a different Euphronios vase or it could have been made much later. Experts, however, have not had access to the works in Basso’s collection or to any history of their ownership.

The antiquities selling case against Monsignor Basso from twenty years ago sheds little light on the history of his collection. In 2000, Monsignor Basso and Monsignor Mario Giordana, a former counsellor at the Holy See’s embassy to the Italian Republic, were investigated by a Rome court for trying to sell fake artworks (including to the Metropolitan Museum) and for breach of art export laws. Prosecutor Francesco Polino sought charges for 14 people including the two Monsignors, alleging that the artworks were fakes or wrongly attributed. The two clerics were accused of using their position at the Vatican to convince buyers of the artworks’ legitimacy, for example, by writing to potential buyers on Vatican stationery. The case was a convoluted one in which even tangentially involved lawyers were accused of soliciting sales (the lawyers successfully defended themselves against this claim).

Example of a painting by Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino, Cardinal Francesco Cennini, 1625, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Public domain.

Certainly, the whole conduct of the 2000 case against Basso and Giordana seems odd. An investigator for the Rome court, Mario Parracciani, is reported to have told the public prosecutor that the archaeological works were authentic and the paintings originals. The prosecutor disagreed. The results of the examination of the alleged fakes don’t appear to have been made public and the fraud cases against the alleged participants were closed.

The fate of the collection – and whether it will ever be publicly vetted – is uncertain. During the 2000 investigation, Basso pleaded his good faith, saying that he intended to sell the artworks in order to raise money for a hospital. The hospital never materialized. For decades, Basso kept the collection in his Vatican apartment, to which Rome’s investigators had no access. In 2020, he donated the collection to the Fabbrica di San Pietro, where he formerly served as archivist. Basso’s art collection is currently stored in 30 fireproof cases under the roof of St. Peter’s Basilica, in Vatican custody.

The Fabbrica di San Pietro is an institution connected to but not part of the actual administration of the Roman Curia. It is tasked with conservation and maintenance of St. Peter’s Basilica. The Fabbrica also came under fire in July 2020 for signing irregular and duplicated contracts with service providers in the massive project to renovate the dome of St. Peter’s. A serious lack of transparency at the Fabbrica resulted in an investigation initiated by Pope Francis and seizure of the Fabbrica’s records by the ‘promoter of justice’ (prosecutor) at the Vatican City State Court. The Pope has also replaced some top staff, appointing (now) Archbishop Mario Giordana (a subject of Rome’s investigation 22 years ago) as extraordinary commissioner at the Fabbrica di San Pietro to clean up the mess there. It appears likely that the minor matter of seventy or so artworks stored under St. Peter’s dome, and of Italy’s case regarding the Euphronios krater, will remain a mystery for now.

Scholarly Review of Scholarly New Exhibit at Capitoline Museum

Domed ceiling with Athena in the Capitoline Museum, Rome Athena in Musei Capitolini, 21 April 2015, Author Livioandronico2013, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Curators as well as future museum visitors will appreciate a thoughtful review by Roman scholar Christopher Siwicki in the February 2023 issue of Art & Object of a new exhibition, ‘Rome of the Republic: The Story of Archaeology.’ The review, entitled ‘New Capitoline Museums Exhibit Will Delight Archaeologists, Not Tourists’ is appreciative of the spectacular quality of a number of objects in the exhibition and of the tremendous amount of information of value to the specialist it contains.

Siwicki’s own photographs, which illustrate the review, provide striking visual examples of what scientific archaeology can contribute to art history, such as the reconstructed statues of the gods Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva from a temple on the via Latina from the first century BCE. However, Dr. Siwicki also points out the challenges of presenting the art, architecture, technology, and social structure of five centuries of Republican Rome in a didactic narrative that neither overwhelms nor dumbs-down the story. In this instance, he says, much of the exhibition overwhelms the non-expert viewer.

While some potential visitors may find the review discouraging, Dr. Siwicki’s patient, respectful exposition of the exhibition’s curators attempts to explain Roman society through archaeological excavations of its remains – sometimes successfully, other times less so, will hopefully encourage a visit to what is clearly a show of great interest to enthusiasts of all things Roman and which may tempt beginners in the field to learn much more.

In Switzerland… Geneva Court Orders Ali Aboutaam to pay Legal Costs and Gives Him a Suspended Sentence

After an extensive, six-year investigation of the provenance of approximately 15,000 objects in the inventory of Phoenix Ancient Art, Swiss antiquities dealer Ali Aboutaam was found guilty of violating Swiss cultural property law with respect to a total of eighteen objects from the inventory. These eighteen pieces were ordered confiscated by the Geneva Police Tribunal for lack of sufficient documentation. The rest of the inventory is being returned to Phoenix Ancient Art.

Ali Aboutaam. Image via Phoenix Ancient Art.

Mr. Aboutaam has stated that he voluntarily identified another 40 objects he deemed questionable and has offered them to the authorities for return. He told the Art Newspaper, “…let the record be clear that not a single piece was proven to have been stolen or illegally obtained. On the contrary, the painstaking investigation ended up positively vetting 99.9% of the Geneva holdings…”

Aboutaam was also accused of asking “art experts or collaborators of Phoenix Ancient Art to fake invoices or provenance documents.” Four of the accused experts were found guilty. In addition, he was convicted of paying an intermediary to import antiquities in violation of Swiss law. The court fined Aboutaam 440,000 Swiss francs for legal expenses and gave him a suspended sentence of 18 months.

The lengthy investigation and court process has entailed significant changes of posture among the Swiss authorities. The initial seizure took place in 2017. In 2018, the court released around 5,000 antiquities back to the gallery, saying at the time that 6,000 remaining in its possession were suspect. A terracotta animal initially described as Mesopotamian was returned after authorities read the label, “To Daddy, with love,” and correctly identified it as made by Aboutaam’s eleven-year-old daughter.

Forty-six objects will remain in government custody. According to Aboutaam, the Swiss authorities do not know the countries of origin and the pieces have not been claimed.

Sarpedon’s body carried by Hypnos and Thanatos (Sleep and Death), while Hermes watches. Side A of the “Euphronios krater”, Attic red-figured calyx-krater signed by Euxitheos (potter) and Euphronios (painter), ca. 515 BCE. Formerly in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY Returned to Italy and exhibited in Rome, 2008. Photo by Jaime Ardiles-Arce.

Sarpedon’s body carried by Hypnos and Thanatos (Sleep and Death), while Hermes watches. Side A of the “Euphronios krater”, Attic red-figured calyx-krater signed by Euxitheos (potter) and Euphronios (painter), ca. 515 BCE. Formerly in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY Returned to Italy and exhibited in Rome, 2008. Photo by Jaime Ardiles-Arce.