Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance – Written Testimony submitted to Cultural Property Advisory Committee, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, U.S. Department of State, on the Republic of El Salvador’s Request for Extension of a Memorandum of Understanding under the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act – Submitted September 16, 2024

The Committee for Cultural Policy (CCP)[1] and Global Heritage Alliance (GHA)[2] jointly submit this testimony on the Republic of El Salvador’s request for an extension of Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the United States and El Salvador under the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act[3] (CPIA). The U.S. first imposed emergency restrictions on imports at the request of El Salvador in 1987.[4] Bilateral agreements began in 1995. If the current the agreement is renewed, it will be the eighth in a consecutive line of agreements with El Salvador.[5]

PRECIS

Conquistador Pedro de Alvarado (Tomás Povedano), 1906, 23 May 2019 by Jl FilpoC, CCA-SA 4.0 Int’l license.

The Cultural Property Advisory Committee is tasked with determining whether the U.S. should extend its Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with El Salvador, focusing on whether the import restrictions effectively deter looting, as required by law. Despite 37 years of these restrictions, looting continues, and there is little evidence they have been effective. Critics argue that the ongoing destruction of cultural sites in El Salvador, often linked to government-backed development projects, suggests that the country has failed to protect its heritage. Additionally, El Salvador has not engaged in cultural exchanges, such as museum loans, with the U.S., further questioning the value of extending the MOU. Proponents of the extension claim looting would worsen without the restrictions, but there is no concrete evidence to support this. The broad scope of the restrictions and the lack of significant impact on looting call into question whether the MOU meets the legal requirements of the Cultural Property Implementation Act. Ultimately, the Committee is urged to deny the renewal, given the ongoing failures in protecting El Salvador’s heritage.

A 37 Year History of Import Restrictions with El Salvador

The Cultural Property Advisory Committee is responsible for making recommendations on whether the United States should extend the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with El Salvador. The extension is dependent on satisfying four key determinants. One critical determinant is whether the import restrictions would substantially contribute to efforts in deterring looting, as outlined in 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(C)(i).

El Salvador 1894 3c allegorical figure of El Salvador. Seebeck essay, unadopted color. The issues of 1890 – 1899 were printed by the Hamilton Bank Note Co. in New York.

The Committee for Cultural Policy and the Global Heritage Alliance have raised concerns in the past regarding whether import restrictions have effectively reduced looting in El Salvador. Despite 30 years of U.S. import restrictions, in which antiquities and later, colonial artworks have been blocked from entry to the United States, the CPAC has stated that looting remains a problem. All applications for MOU extensions have acknowledged ongoing looting, which casts serious doubt on the effectiveness of the MOUs in curbing it. One must ask, if a policy has not achieved the goal of halting looting, despite being faithfully enforced for thirty-seven years by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and despite there being no U.S. market for looted materials, is it justified?

The answer is “No, El Salvador’s renewal request does not meet the statutory criteria under the Cultural Property Implementation Act.”

Through no fault of CBP or lack of U.S. enforcement, the import restrictions have not achieved their mandated goal of deterring pillage.[6] That tells us that the problem is not with the United States, but with the successive governments of El Salvador having failed for thirty-seven years to take the necessary steps to protect the country’s cultural heritage and archaeological sites. Reports to the CPAC in 1998, 2004, 2009 and later indicated that looting was continuing[7] – and site destruction continues today, albeit primarily for government-sanctioned development and not for artifacts, as a by-product of commercial and infrastructure building.

El Salvador Pavillion, Shanghai Expo 2010 World’s Fair, 17 September 2010, photo by Gary Lee Todd, Ph.D., CCO 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Another concern is that while the MOUs have blocked access to Salvadoran materials to U.S. private and institutional collectors, the government of El Salvador has not made the effort to bring the art of El Salvador to the American public. There have not been museum loans or traveling exhibitions from El Salvador to give the U.S. public has access to its arts. After thirty-seven years, there is justifiable skepticism that renewal would meet the statutory requirements of the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA) that the application of the import restrictions is consistent with “the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.”[8]

Some proponents argue that looting would be worse without the MOU, but this argument is specious. To meet the statutory requirements for an MOU extension, evidence must be provided showing that the MOU has been effective in reducing looting. Decisions must be based on factual evidence, not speculation or assumptions. Any recommendation for an extension should be based on clear proof that the statutory requirements, particularly those concerning the deterrence of pillage through import restrictions, have been met. The statute also requires that “remedies less drastic than the application of [import] restrictions… are not available.” Clearly, the government of El Salvador has encouraged development at and near sites. It has been the problem, not part of the solution.

Background on El Salvadoran Heritage

Main pyramid (San Andrés, El Salvador), photo from the book “Two Hundred Days in Latin America”, 16 April 2015, photo Victor Pinchuk, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

El Salvador was part of the ancient Mayan civilization, which extended from southern Mexico to Central America, including Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, and Nicaragua. The Maya were one of the most advanced pre-Columbian civilizations, although they were never politically unified. Today, El Salvador has some 20 identified Mayan ruins, only some of which have been partially or completely excavated.

Key Archaeological Sites in El Salvador

- San Andrés: This site was intermittently occupied for over 2,000 years before 1200 AD and served as the capital of Cuzcatlán and a major regional religious center. Excavations have focused on the central plaza and the pyramids.

- Tazumal: Located in the Santa Ana department, 40 miles northwest of San Salvador, Tazumal showcases Toltec influence, with its primary pyramid standing 75 feet above the main plaza. The site also includes palaces, tombs, and is adjacent to the Casa Blanca Maya site, which contains five pyramids. The Tazumal Museum houses an Olmec-style stone figure, pottery, and ceremonial stone belts.

- Cihuatán: Situated 22 miles north of San Salvador, near Aguilares along the North Trunk Road, Cihuatán is El Salvador’s largest Maya site. Excavations have uncovered ball courts, palaces, pyramids, and defensive walls. The site encompasses seven subsidiary residential areas, although only one has been fully explored.

Archaeological site of Joya de Ceren, 16 May 2012, Mariordo (Mario Roberto Duran Ortiz), CCA-SA 3.9 Unported license.

El Salvador is also home to numerous smaller but equally significant archaeological sites, such as Joya de Cerén Archaeological Park, El Salvador’s only World Heritage site.[9] This pre-Hispanic farming community was buried by the eruption of the Laguna Caldera volcano around AD 600. The exceptional preservation of Joya de Cerén under volcanic ash provides unique insights into the daily lives of ancient Central American farming populations. Discovered accidentally in 1976 during the construction of grain-storage silos, the site has undergone continuous excavations since 1989. The volcanic ash preserved the architecture and artifacts in their original positions. While Joya de Cerén does not have artistically rich finds or the attributes of a high civilization, it is the best-preserved example of a pre-Hispanic village in Mesoamerica. The site contains 18 structures, 10 of which have been fully or partially excavated, revealing a range of civic, religious, and household buildings. The buildings are primarily constructed from earth, with some featuring rammed earth and wattle-and-daub techniques, which are more resilient. Like Pompeii and Herculaneum in Italy, Joya de Cerén was preserved due to its sudden burial and has provided unique information about the village communities of ancient Central American civilizations.

International funding via UNESCO for the preservation of Joya de Cerén took place between 1992 and 2003, with eight approved requests for Joya de Cerén and two others in El Salvador totaling $227,500 USD.[10] The last UNESCO assessment of the Joya de Cerén site was in 2003, and the last funding approved was $25,000 in 2011 (2014 proposed work was not approved by UNESCO), creating a significant gap in international support. While excavations continue, the preservation of the fragile earthen structures and artifacts is critical. UNESCO reports that despite past international support, commitment from El Salvador’s government is essential to ensure the site’s ongoing preservation.[11]

Failures of El Salvador’s Government Oversight and Accountability

Ilamatepec (Santa Ana) Volcano, Santa Ana – El Salvador, 6 March 2019, Author Rômulo Gama Ferreira from Vitória-ES.

El Salvador has a tumultuous political and economic history marked by ongoing failures in protecting its ancient cultural sites. Over thirty-seven years and under a variety of governments, El Salvador has not safeguarded its cultural heritage sites. Many sites have been continuously threatened by urban development, environmental degradation, and looting, necessitating preservation efforts that the government has consistently failed to provide.

The aftermath of the civil war and the country’s limited resources have repeatedly been used as excuses for failing to implement provisions of cultural preservation agreements. A June 1998 Interim Report issued by CPAC noted continuing looting, as did testimony a decade after the first MOU in 2004 by Karen Bruhns and Paul Amaroli.[12] Notable examples of the government’s failure to protect sites include:

- Cihuatán and Sitio de Jesús Destruction: One of the most significant failures to protect ancient sites occurred at the Cihuatán Archaeological Park. After the relationship between the government and the Fundación Nacional de Arqueología de El Salvador (FUNDAR), a key non-governmental conservation organization, ended in 2009, significant destruction took place. A government-backed housing project destroyed approximately 3.5 acres of the Cihuatán site, leading to widespread looting during the construction of 38 homes, with plans for 300 more homes. Evidence of government involvement was clear, as machinery bearing insignias from the Ministry of National Defense, Engineer Command of the Armed Forces, and other governmental bodies was used at the site. A similar pattern of destruction occurred at Sitio de Jesús, despite repeated warnings by FUNDAR to the government.[13]

Site destruction and looting extend beyond Cihuatán and Sitio de Jesús, with several other pre-Hispanic and Classical period sites “destroyed by urban development.”[14]

- Chalchuapa: A region with over seven pre-Hispanic sites, many of which have been plundered and destroyed due to urban expansion.

- San Andrés: A Classical period site that has experienced ongoing looting around the perimeter of the archaeological park.

- Guazapa: Postclassic period sites in this region partially destroyed for stone for building materials.

- Guija: A site with significant rock art and the Classical period site of Igualtepeque, which has been continuously vandalized.

- Asanyamba: A complex Classical period site that has been looted since the late 1970s.

- Cara Sucia: A Postclassic site that has witnessed the creation of over 5,000 looting holes since the early 1980s.

- Madre Selva: Destroyed in 1993, believed to be connected to the Cuscatlán domain.

- Carcagua: Destroyed in 1998 to make way for a bus terminal project that was never completed.

- Rosita: Partially destroyed in 1999 for residential development.

- Santa Lucia: A Classical period site destroyed in 2001 to make way for settlements after the 2001 earthquakes.

- El Cambio: A Preclassic site partially destroyed by road paving in 2008, with involvement from both government and private sectors.

- El Nispero: Partially destroyed in 2009 due to government transmission line installations.

- Las Marías: The largest pre-Hispanic site in El Salvador, damaged by looting and crop activity since 2000.

- Cajete: A site under constant looting since the 1980s.

- Casa Quemada and El Chaparral: Among 10 other sites threatened by the construction of the El Chaparral dam.[15]

San Salvador, June 12, 2011, photo by randreu, Panoramio, CCA 3.0 Unported license.

Despite the MOU’s intention to protect these sites, government-backed projects, including residential developments and infrastructure, have contributed to significant site destruction, even after warnings from heritage organizations. The transition of cultural site management away from a non-governmental preservation organization and to government authorities motivated by economic interests has worsened the vulnerability of sites throughout El Salvador.[16]

Lack of Progress Despite International Agreements

Although the U.S. has imposed import restrictions for thirty-seven years with the goal of curbing looting, there is little evidence to suggest these measures have effectively reduced archaeological destruction. While some argue that without the MOU, the situation would be worse, such claims fail to acknowledge that destruction in El Salvador is due primarily to government-tolerated private sector interests and government’s lack of accountability. This raises serious concerns about the country’s commitment to protecting its cultural heritage. It calls into question the MOU’s ability to meet its objectives and underscores the need for the CPAC to undertake a critical reassessment of its effectiveness.

Alcaldía Municipal de Santa Ana, El Salvador, 11 June 2013, photo YessicaGuerra19, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

El Salvador’s failure to establish incentives for the protection and retention of cultural objects makes it unlikely that the country can meet the legal criteria set forth in the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA). The government’s focus on other pressing issues, such as gang violence and corruption, has overshadowed its efforts to protect cultural heritage. Along with Guatemala and Honduras, El Salvador has long formed part of the region’s largest concentration of corruption, drug trafficking, and gang violence.

Despite President Nayib Bukele’s recent militarization of state security and crackdown on gangs, and the government’s highly publicized fight to end corruption, according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, El Salvador ranks 126 out of 180 countries, with a corruption score of 31. This score represents a decline from last year, indicating that corruption is worsening.[17]

Nayib Bukele speaks at his inauguration ceremony, 2 June 2019, Office of U.S. Commerce Secretary, public domain.

Despite government claims of fighting corruption, its actions often target political opponents while investigations involving current officials from Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas party have not been pursued with the same intensity. By July 26, 2024, El Salvador’s Attorney General’s Office had opened investigations into 285 cases of corruption, involving charges such as embezzlement, extortion, and bribery.

The U.S. State Department has reported that President Bukele’s so-called “war on corruption” includes high-profile cases against former presidents and municipal officials.[18] However, critics argue that Bukele’s administration is engaging in selective justice, using anti-corruption measures as a political tool to weaken opponents rather than establishing a genuine rule of law.

This discrepancy raises concerns about the government’s commitment to real reform. Systemic issues, including a lack of transparency and accountability, persist. The continued influence of political elites over the judiciary makes it difficult for El Salvador to meet the CPIA’s legal criteria, which require a credible legal framework and genuine enforcement of cultural property protections.

Weakened Democratic Safeguards and Judicial Independence

Under Bukele’s administration, El Salvador’s democratic safeguards have also been systematically weakened. The appointment of political allies to key positions in the Supreme Court and the Attorney General’s Office has undermined the judiciary’s independence, exacerbating the country’s corruption crisis. The removal of independent judges and prosecutors has deepened a sense of impunity for those in government favor, further weakening efforts to prosecute crimes related to illegal development projects.

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo participates in a signing ceremony for the CSL Lease Extension with Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, July 21, 2019, photo U.S. Department of State.

The executive branch’s control over the judiciary threatens fundamental democratic processes as courts increasingly serve as political tools rather than impartial arbiters of justice. President Bukele’s administration has been widely criticized for human rights violations, particularly as innocent citizens, especially children, have been caught up in its “war against gangs.” The judiciary has played a role in enabling the continued detention of suspects without due process. This environment of arbitrary detention and the intimidation of judges and prosecutors make it even harder to enforce laws that protect cultural property against development and abuses of indigenous peoples by the elite.

The ongoing corruption crisis, coupled with political instability and human rights abuses, suggests that the preservation of cultural sites and the protection of artifacts will remain secondary concerns for the government. This further puts its ancient sites and treasures at risk.

Reevaluating the MOU with El Salvador in Light of Ineffective Import Restrictions and Government Failures

Lanzamiento de las Fuerzas Especailizadas de Reacción El Salvador, FES.20 April 2016, Presidencia El Salvador, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the United States and El Salvador aims to protect cultural property by imposing import restrictions on archaeological materials and ecclesiastical ethnological material (from the Colonial period through the first half of the twentieth century, from A.D. 1525 to 1950).[19] Submissions to the CPAC will likely claim that other market countries have adopted similar restrictions. However, even if these claims are accurate, there is no evidence to suggest that such restrictions have significantly reduced looting in El Salvador.

According to market sources, including art dealers, auction houses, and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), there is no significant legitimate market for El Salvadorian archaeological material in the United States. The existence of an illegitimate market for these objects is also questionable. Yet after 37 years of MOUs, there has been little to no impact on the rate of looting in El Salvador, suggesting that the U.S. restrictions may be ineffective.

Yagu El Salvador, 27 April 2022, Resel Cosmus.

Despite restrictions, Prehispanic objects continue to circulate in the European market and collecting of Pre-Columbian art has expanded to the Middle East and China. It is likely that El Salvadorian objects are included due to their similarity to artifacts from neighboring countries like Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. The difficulty in distinguishing between objects from these countries poses a challenge in curbing the illicit trade of El Salvadorian artifacts.

Overly Broad Scope of the Designated List

The Designated List under the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA) has raised significant concerns for being overly broad and failing to meet statutory requirements. It oversteps the authority granted by the CPIA by including overly generalized categories and descriptions, making it difficult for both importers and customs officials to properly interpret and enforce the restrictions. These deficiencies lead to questions about whether the list effectively fulfills its intended purpose.

Woman and girl in El Salvador making maize dough, likely to be used to make tortillas, 1910, by National Geographic Society, public domain.

The Designated List is often criticized for being too broad and failing to align with the CPIA’s intent of narrowly tailored import restrictions. By including generic categories of artifacts, the Designated List restricts items that may not meet the CPIA’s definition of cultural significance. For example, archaeological vessels are generically listed as “cylindrical vessels, bowls, dishes, and plates, jars.” This broad description is overly inclusive and fails to distinguish between objects of true cultural importance and ordinary artifacts. Such descriptions result in blanket restrictions, which are contrary to the CPIA’s goal of targeting specific items of cultural and archaeological significance.

With respect to both archaeological and ethnological materials, the current restrictions go far beyond any rational interpretation of Congress’ intent in the Cultural Property Implementation Act. The all-inclusive definition of “cultural property” are clearly not limited to items of “cultural significance” in the statute[20], and as Congress set forth in its 1982 Senate Report.[21]

The 2020 El Salvador Designated List includes “ecclesiastical material from the Colonial period through the first half of the twentieth century ranging in date from approximately A.D. 1525 to 1950 that was made by artisans and used for religious purposes.” In striking contrast, the 1982 Senate Report states:

Girl at the Palacio Nacional de El Salvador, 31 August 2023, Andreitahdz 93, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

“Ethnological material” includes any object that is the product of a tribal or similar society, and is important to the cultural heritage of a people because of its distinctive characteristics, its comparative rarity, or its contribution to the knowledge of their origins, development or history. While these materials do not lend themselves to arbitrary age thresholds, the committee intends this definition, to encompass only what is sometimes termed “primitive” or “tribal” art, such as masks, idols, or totem poles, produced by tribal societies in Africa and South America. Such objects must be important to a cultural heritage by possessing characteristics which distinguish them from other objects in the same category providing particular insights into the origins and history of a people. The committee does not intend the definition of ethnological materials under this title to apply to trinkets and other objects that are common or repetitive or essentially alike in material design, color, or other outstanding characteristics with other objects of the same type, or which have relatively little value for understanding the origins or history of a particular people or society. An agreement or emergency action would also not apply to ethnological material produced by more technologically advanced societies.”[22]

In explanatory text attempting to justify inclusion of ethnological material that does not meet Congress’ definition, the 2020 El Salvador Designated List states,

“Salvadoran artisans created paintings, sculptures, furniture, metalwork, textiles, and craftwork for religious use in churches and cofradias, or ecclesiastical lay organizations, until the mid-twentieth century. This ethnological material was not mass-produced or industrially produced, and most works were anonymous.”[23]

Catedral nuestra señora de Santa Ana, Santa Ana, El Salvador, 14 August 2011, photo by Rolland Alexander Nunfio Reyes. CCA-SA 3.9 Unported license.

The inclusion of ethnological objects in violation of the statute is now common in Designated Lists, but repeating a wrongful interpretation does not legitimate it.

The CPIA was designed to balance the competing interests of museums, the art market, the U.S. public, and archaeologists, while safeguarding the cultural property of source nations. Congress viewed import restrictions as drastic measures and allowed them only if stringent criteria were met. However, the current Designated List does not adhere to these standards, as it imposes broad restrictions without sufficiently demonstrating the cultural significance of the items being restricted, as required by the CPIA. The CPIA specifies that restricted items must be of cultural significance and at risk of pillage to justify import restrictions. Generic descriptions do not meet this threshold.

In its current form, the Designated List fails to meet the narrow and balanced approach required under the CPIA. This leads to ineffective enforcement and unnecessary restrictions on legitimate trade. To ensure that the goals of the CPIA are met, the Committee should re-evaluate the Designated List and implement revisions that provide clear, focused restrictions on items of cultural significance. This would allow for better protection of cultural heritage while also supporting legitimate trade and public interest.

The CPAC’s Conclusion on Market Restrictions

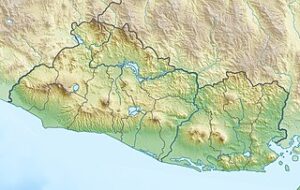

Physical location map of El Salvador, Equirectangular projection, 28 March 2010. Own work, using map data from administrative map by NordNordWest. The relief was created from SRTM-3 relief data, Author Carport, CCA-SA 3.9 Unported license.

With respect to justifying import restrictions based on their being an active U.S. market for looted materials, El Salvador has provided no evidence that this is the case. El Salvador is not known for the artistic quality of its antiquities, nor for their high value. Certainly, there are plenty of Pre-Columbian materials circulating in the U.S., as there has been a very active import trade going back to the early 20th century. Pre-Columbian objects imported several generations before continue to circulate and find new owners. Few are from El Salvador.

With respect to the U.S. being a primary market for El Salvadoran looted objects – after 37 years of import restrictions, any El Salvadoran objects in circulation in the U.S. have been in circulation for a very long time. In order to determine if the criteria of the U.S. being a primary market is the case, in order to meet the statute, the CPAC is faced with two possible conclusions:

- Other market countries have adopted similar restrictions, but there has been no significant reduction in looting.

- Other market countries have not adopted similar restrictions, and after 37 years, the “reasonable period of time” for such adoption, as stipulated under 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(C)(i), has long passed.

In either case, the Committee must question whether the required determinations for the MOU are being met.

Misalignment with CPIA’s Purpose and Criteria

First set of stamps of El Salvador with volcano, 1867, Government of El Salvador, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

The MOU requires El Salvador to meet all four key legal criteria under the Cultural Property Implementation Act. However, El Salvador has failed to:

- Effectively implement import restrictions that deter looting.

- Protect its cultural property from destruction, particularly in the face of government development projects.

El Salvador serves as a clear, cautionary example of the limitations of the current system of MOU renewals under the Cultural Property Implementation Act. Despite repeated renewals of the MOU, archaeological and heritage losses in El Salvador persist, indicating the ineffectiveness of U.S. import restrictions in halting looting and site destruction. Given these failures, the CPAC must reassess the validity of extending the MOU. Despite almost four decades of import restrictions, the lack of concrete results calls into question the overall efficacy of such restrictions in addressing looting and the destruction of cultural property in El Salvador. After thirty-seven years, the CPAC should acknowledge that El Salvador’s request for yet another extension should be denied.

Kate Fitz Gibbon, Committee for Cultural Policy, Inc.

Elias Gerasoulis, Global Heritage Alliance, Inc.

[1] The Committee for Cultural Policy, Inc (CCP) is an educational and policy research organization that supports the preservation and public appreciation of art of ancient and indigenous cultures. CCP supports policies that enable the lawful collection, exhibition, and global circulation of artworks and preserve artifacts and archaeological sites. We deplore the destruction of archaeological sites and monuments and encourage policies enabling safe harbor in international museums for at-risk objects from countries in crisis. We defend uncensored academic research and urge funding for museum development around the world. We believe that communication through artistic exchange is beneficial for international understanding and that the protection and preservation of art from all cultures is the responsibility and duty of all humankind. The Committee for Cultural Policy, POB 4881, Santa Fe, NM 87502. www.culturalpropertynews.org, info@culturalpropertynews.org.

[2] Global Heritage Alliance (GHA) advocates for policies that will restore balance in U.S. government policy in order to foster appreciation of ancient and indigenous cultures and the preservation of archaeological and ethnographic artifacts for the education and enjoyment of the American public. GHA supports policies that facilitate lawful trade in cultural artifacts and promotes responsible collecting and stewardship of archaeological and ethnological objects. The Global Heritage Alliance. 1015 18lh Street. N.W. Suite 204, Washington, D.C. 20036. http://global-heritage.org/

[3] The Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, 19 U.S.C. §§ 2601, et seq.

[4] Import Restrictions on Archaeological Material From El Salvador, [T.D. 87-104], September 4, 1987, effective September 11, 1987, https://eca.state.gov/files/bureau/es1987eafrn.pdf.

[5] The first bilateral agreement between the United States and El Salvador was signed March 8, 1995. Subsequently the agreement was renewed and expanded over time to cover colonial art in 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020.

[6] 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(C)(i)

[7] Extension of Import Restrictions on Archaeological Material and Imposition of Import Restrictions on Ecclesiastical Ethnological Material From El Salvador, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/03/18/2020-05694/extension-of-import-restrictions-on-archaeological-material-and-imposition-of-import-restrictions-on

[8] 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(D)

[9] UNESCO World Heritage Convention, Joya de Cerén Archaeological Site, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/675/assistance/

[10] UNESCO, World Heritage Convention, El Salvador, https://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/sv.

[11] UNESCO, World Heritage Convention, Joya de Cerén Archaeological Site, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/675

[12] Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), “Statement of the Association of Art Museum Directors Concerning the Proposed Extension of the Bilateral Agreement between the United States of America and the

Republic of El Salvador,” (2014 Statement), October 7, 2014, https://cms.aamd.org/sites/default/files/key-issue/AAMD-CPAC%20-%20El%20Salvador%20Written%20Testimony%20Concerning%20MOU.pdf, citing to Testimony of Dr. Karen Bruhns and Paul Amaroli on Behalf of the Society of American Archaeology Before the Cultural Property Advisory Committee on the Renewal of the Memorandum of Understanding Between the United States and El Salvador, November 18, 2004 at 2.

[13] AAMD, 2014 Statement, fn 11-15.

[14] AAMD, 2014 Statement, fn 16-21.

[15] Id.

[16] AAMD, 2014 Statement

[17] Transparency International, El Salvador, https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2023/index/slv.

[18] U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices El Salvador Section 4, Corruption in Government, https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/el-salvador/

[19] U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Department of Homeland Security; Department of the Treasury, Extension of Import Restrictions on Archaeological Material and Imposition of Import Restrictions on Ecclesiastical Ethnological Material From El Salvador, 19 CFR Part 12 [CBP Dec. 20-04], RIN 1515-AE53, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/03/18/2020-05694/extension-of-import-restrictions-on-archaeological-material-and-imposition-of-import-restrictions-on

[20] As defined under section 202(2i) of the Cultural Property Implementation Act, “archaeological material” includes any object which is of cultural significance, which is at least 250 years old, and which normally has been discovered through scientific excavation, clandestine or accidental digging, or exploration on land or under water.

[21] S. Rep. 97-564 at 2, 12 (2d Sess. 1982).

[22] S. Rep. 97-564 at 5, 12 (2d Sess. 1982).

[23] U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Department of Homeland Security; Department of the Treasury, Extension of Import Restrictions on Archaeological Material and Imposition of Import Restrictions on Ecclesiastical Ethnological Material From El Salvador.

San Andres pyramids, La Acropolis Mayan site

San Andres pyramids, La Acropolis Mayan site