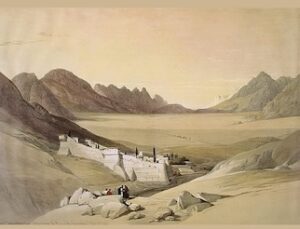

The monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai, from the south. Coloured lithograph by Louis Haghe after David Roberts, 1849. Wellcome Trust. CCA 4.0 International license.

“The recent judicial actions which threaten to confiscate the monastery’s property and disrupt its spiritual mission are deeply troubling. Such measures not only violate religious freedoms but also endanger a site of immense historical and cultural importance.” Archbishop Elpidophoros, the Primate of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, May 29, 2025, quoted in The Pillar, “What’s happening at Egypt’s St. Catherine’s Monastery?.”

Egypt’s Great Transfiguration Project, a massive state-sponsored tourism megaproject in South Sinai, poses an existential threat to the unique cultural, spiritual, and environmental heritage of Saint Catherine’s Monastery and nearby city of Saint Catherine, the Sinai landscape, and the Jabaliya Bedouin community.

While Egyptian authorities frame the project as a “gift to the world,” intended to promote interfaith harmony and spiritual tourism, reports from World Heritage Watch, UNESCO, local communities, and

international religious leaders demonstrate that the project, which began in 2021 is causing irreversible harm to a fragile and sacred landscape, violating indigenous rights, undermining religious freedoms, and breaching Egypt’s obligations under the World Heritage Convention. The failure to of the Egyptian government to adhere to global standards of protection for the monastery should also raise serious concerns about the current candidacy of Egypt’s Khaled El-Enany for UNESCO Director-General.

Together with the damage done by the Great Transfiguration Project, there are equally alarming consequences stemming from a May 28, 2025 160-page ruling by Egypt’s Court of Appeals on the property rights to the Monastery of Saint Catherine. This ruling not only curtails centuries-long recognized property rights held by Saint Catherine’s religious community; it could have far reaching effects on other Christian, Jewish and Muslim religious establishments across Egypt as well.

The Sacred Autonomous Royal Monastery of Saint Catherine

Saint Catherine’s Monastery, founded in the 6th century by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, is the world’s oldest continuously inhabited Christian monastery and home to one of the world’s most important ancient libraries, said to be second only to the Vatican Library. The monastery is revered by Christians, Jews, and Muslims alike as the site of Moses’ encounter with the Burning Bush and the giving of the Ten Commandments.

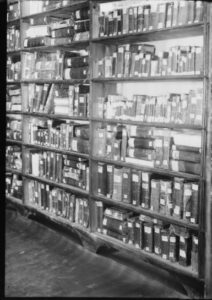

In 2002, UNESCO recognized the monastery and its surrounding landscape as a World Heritage Site of “immense spiritual significance.” Its library contains more than 3,300 manuscripts in Greek, Syriac, Arabic, Coptic, Armenian, and other ancient languages—including the famed Codex Sinaiticus (mid-4th century), one of the earliest complete Christian Bibles.

To Sinai via the Red Sea, Tor, and Wady Hebran. Monk climbing up to his cell-chapel [Monastery of St. Catherine], between 1900 and 1920, Library of Congress, public domain.

However, after several years of negotiations between Egypt’s government and the Hellenic Republic that resulted in an agreement granting the monastery’s religious community’s property rights, the decision by the Sinai’s Ismailia Administrative Appeal Court failed to acknowledge the monastery’s title or legal possession. According to a legal analysis by Dean Kalimniou in the Greek Herald (see Appendix), the monks were granted only use of the property – “the right to inhabit, maintain, and perform religious functions within the core precincts of the monastic enclosure.” All lands and property beyond this perimeter, including agricultural lands, chapels, and ancillary structures were controlled by the Egyptian state and subsumed within the public domain.

The revised terms of the ruling were firmly rejected by the monastery’s Abbot, Archbishop Damianos, and have precipitated a further diplomatic rift between Egypt and the Greek government.

At the same time, the massive, state-sponsored development project taking place today at the nearby city of Saint Catherine in the Sinai shows how little recognition the Egyptian state gives both to traditional property rights held for centuries – and to its obligations under modern treaties to protect cultural and environmental heritage.

Great Transfiguration Project: Scope and Stated Aims

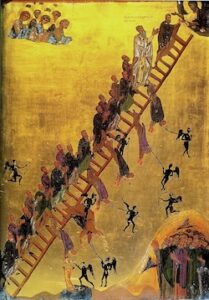

The Ladder of Divine Ascent or The Ladder of Paradise. A 12th-century icon described by John Climacus. Monastery of St Catherine, Mount Sinai. St John Climacus described the Christian life as a ladder with thirty rungs. The monks are tempted by demons and encouraged by angels, while Christ welcomes them at the summit. Image: Pvasiliadis. 11 July 2007, public domain

In 2021, the Egyptian government launched the Great Transfiguration Project, personally sponsored by President Abdel Fattah El Sisi. The Great Transfiguration Project involves building a mega-tourist hub in the tiny nearby city of Saint Catherine. Within the project’s umbrella are more than a dozen projects that were estimated to cost four billion Egyptian pounds (about $220 million) in 2022. The overall project has been overseen by the New Urban Communities Authority, a state-owned enterprise started in 1979 that is affiliated with Egypt’s Ministry of Housing.

Framed by Egyptian state-controlled media as a way to promote Egypt’s “interfaith heritage” and to establish Saint Catherine as a global hub for “spiritual, environmental, and wellness tourism,” the project involves sweeping infrastructure and commercial development in the monastery’s surrounding region. According to official Egyptian sources and international reports, the project includes:

- New roads and highway networks linking Saint Catherine’s with Red Sea resorts (Sharm el-Sheikh, Dahab), cutting through protected landscapes.

- Expansion of Saint Catherine International Airport into a major tourist hub.

- Construction of luxury hotels and “eco-lodges,” including 192 hotel rooms and 56 suites.

- Mountain Hotel with 144 rooms and suites.

- New residential neighborhoods (notably Zaitouna), including 21 hotel complexes with 546 homes.

- Tourist bazaar and shopping centers, covering 1500m².

- Peace Square with a theater, museum, event spaces, and conference halls.

- Flood control measures, artificial landscaping, and hydrological engineering in the Holy Valley.

- Expansion of city utilities (electricity, water pipelines, government buildings).

The Egyptian Prime Minister described the project as “Egypt’s gift to the entire world and all religions,” positioning it as a model of religious coexistence. However, independent evaluations tell a radically different story.

UNESCO’s Warnings of Violations of the World Heritage Convention and Other Agreements

The dramatic changes to the city of Saint Catherine and the lands surrounding the monastery have raised alarms throughout the world heritage community. In 2023, UNESCO formally requested Egypt to:

- “Halt the implementation of any further development projects.”

- “Conduct a full impact evaluation.”

- “Prepare a conservation plan” for the affected area.

Tourism infrastructure development of gigantic proportions within the St. Catherine Area, World

Heritage Watch Report, Egypt. Photo: Anonymous, 2024.

As of 2025, Egypt has ignored these recommendations. Construction continues at 24/7 pace, with traditional architecture erased and major plazas, concrete buildings, an “international” airport and high-end hotels now replacing old neighborhoods and new roads accessing additional nearby building sites for more construction and leading to the Sharm El Sheikh port in the Red Sea.

World Heritage Watch reports that the project has “destroyed the integrity of this historical and biblical landscape.” WHW also contends that Egypt’s government is violating not only its obligations under the World Heritage Convention but also Egyptian environmental laws pertaining to protected natural reserves.

Both UNESCO and World Heritage Watch are alarmed by the physical threat to the monastery itself. Vibrations from heavy construction and the new roads threaten the structural integrity of the monastery’s ancient walls. New water systems to serve a vastly expanded population are causing alterations to the region’s microclimates and risk degrading the fragile ecosystem upon which manuscript preservation depends. Mass tourism traffic will overwhelm a site whose spiritual value depends on serenity, solitude, and controlled visitation.

UNESCO has noted that the monastery’s surroundings are part of its universal value; any destruction of the landscape compromises the entire World Heritage designation.

The 2025 decision of the Ismailia Administrative Appeal Court that the Egyptian state owns the land of Saint Catherine’s Monastery and its surrounding religious sites, relegating the monastery to mere “usage rights,” directly contradicts a 2002 UNESCO document in which Egypt acknowledged in writing that ownership of the land and buildings belonged to the Greek Orthodox Church and the Archdiocese of Sinai.

Global religious leaders have condemned the ruling. Archbishop Ieronymos II of Athens described the Egyptian government’s actions as “seizure and confiscation” of monastery property. The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople condemned the state’s move to treat the monks as “mere users of the land,” undermining centuries of ecclesiastical autonomy. Archbishop Elpidophoros, leader of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, declared the situation “deeply troubling” and a threat to religious freedom.

Displacement of the Jabaliya Bedouins

People and tents outside St. Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt

G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, 1925, Library of Congress, public domain.

The Jabaliya Bedouin tribe, whose ancestors were brought to Sinai in the 6th century to serve the monastery, are today an integral part of the monastery’s community. They have historically protected the site and facilitated sustainable tourism.

Under the Great Transfiguration Project, tribal houses have been demolished to make way for luxury construction and tribal cemeteries and sacred sites have been desecrated. Jabaliya workers are being displaced and replaced by thousands of outside laborers. Meanwhile, state security forces are silencing opposition and restricting media coverage. Human rights abuses against the indigenous community have been reported to international monitors. As World Heritage Watch notes: “A new urban world is being built around a people of nomadic heritage.”

Egypt’s UNESCO Candidacy and Global Silence

The Egyptian government’s promotion of the project coincides with its nomination of Khaled El-Enany—former Minister of Tourism and Antiquities and a key architect of the project—for election to the post of UNESCO Director-General.

The election is scheduled for October 2025 in Paris. If elected, El-Enany will become the first Arab and the second African to lead UNESCO since it was established eighty years ago. In multiple interviews, including with the Korea Times, El-Enany has praised Egypt’s heritage policies but has remained silent on the crisis at Saint Catherine’s. His nomination thus presents a serious conflict of interest for UNESCO.

If UNESCO fails to act decisively on the appropriation by the Egyptian government of Saint Catherine Monastery’s rights, the credibility of the entire World Heritage system will be at risk. UNESCO should immediately list Saint Catherine’s as World Heritage in Danger, dispatch an official monitoring mission, demand a halt to construction, require restoration of damaged landscapes, and reaffirm the ownership rights of the Greek Orthodox Church.

A Propaganda Façade: The “Gift to the World”

To Sinai via the Red Sea, Tor, and Wady Hebran. The famous library [Monastery of St. Catherine] G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, 1900. Library of Congress.

The only reasonable response to this blatant hypocrisy is for the U.S. and EU to pressure Egypt diplomatically – and for global tourism organizations to acknowledge the harm being done and boycott the Grand Transfiguration Project.

Update June 7, 2025: Egyptian press reported today that Pope Tawadros II, the head of Egypt’s Coptic Orthodox Church, and Pope Leo XIV, head of the Vatican, had a telephone conversation on June 6 “praising Egypt’s political leadership” for reaffirming that monks at Saint Catherine’s Monastery would not be removed. In fact, the article restated the same restrictions and assertions that the monastery was Egyptian public property, to which Pope Tawadros II vehemently objects.

Appendix: The Legal Arguments Under Egyptian Law

Dean Kalimniou has published an excellent analysis of the legal arguments and issues arising from the 28 May 2025 decision of the Court of Appeals regarding the property rights of the Sacred Autonomous Royal Monastery of Saint Catherine. Kalimniou’s complete article was published in Australia’s The Greek Herald on 6/06/2025 – Explained: The legal battle over Saint Catherine’s Monastery property in Egypt.

Here is a summary:

The core legal conflict lies in reconciling historical possession with formal title requirements under Egyptian law, particularly Law No. 114 of 1946 governing real estate registration. In 1980, Egyptian authorities invited all entities with undocumented landholdings to submit declarations establishing property rights. The Monastery submitted 71 declarations, identifying chapels, agricultural lands, and monastic structures.

In 2015, the Governorate of South Sinai initiated proceedings asserting that these properties were legally state-owned. The Court’s decision rests on two principal legal arguments:

- Law No. 114 of 1946 and the Requirement of Registered Title: Under Egyptian law, proprietary rights are only legally recognized once formally registered in the state’s cadastre. The Monastery’s declarations were not equivalent to registration and did not confer title. The Court invoked the nulla titulus principle—land lacking registered title presumptively belongs to the state.

- Application of Articles 87-90 of the Egyptian Civil Code: These articles define public domain property as land used for public purposes or deemed of historical, cultural, or environmental value. The Court applied this doctrine expansively, categorizing outbuildings, chapels, agricultural plots, and hermitages as falling within the public domain.

The Court argued that heritage preservation and environmental protection constitute legitimate state interests that can override private claims lacking formal documentation. (A cynical conclusion given the actual facts of cultural and environmental destruction now taking place.)

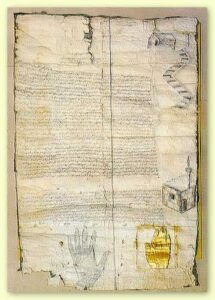

Ashtiname of Muhammad (622 CE; copy: 1517 CE), ratified by the Prophet Muhammad granting protection and other privileges to the followers of Jesus the Nazarene, given to the Christian monks of Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt.

The Court distinguished between religious/spiritual use (which remains protected) and property ownership (which, outside the Monastery’s core precincts, now reverts to the state). The monks retain the right to inhabit and perform religious functions within the main monastic enclosure. However, lands outside this core, even those used continuously by the Monastery, are now considered state property.

Critics argue that Egypt’s legal tradition has historically recognized customary rights based on long-standing, uncontested possession—especially for religious and tribal communities. The Court’s formalist approach disregards this dimension, prioritizing modern registration over ancient tenure.

The Ashtiname of the Prophet Muhammad, traditionally viewed as protecting the Monastery’s rights, was not addressed by the Court. Though its enforceability is debated, its symbolic and historical significance is immense; its exclusion represents a serious omission.

The ruling may conflict with Egypt’s obligations under the UNESCO 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage and the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property. While the case does not arise in armed conflict, both instruments commit Egypt to protecting religious and cultural institutions embodying intangible traditions.

The ruling could affect other religious institutions—Christian, Muslim, Jewish—whose landholdings predate modern cadastral systems. It introduces major legal uncertainty for any unregistered religious property in Egypt.

Sources

Jerusalem Post Staff, “Egypt and Greece clash over Saint Catherine’s,” Jerusalem Post, June 4, 2025. https://www.jpost.com/christianworld/article-856471

UNESCO World Heritage Site Inscription, 2002. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/954

AFP, “Five things to know about St Catherine’s Monastery,” AFP, June 4, 2025. https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20250604-five-things-to-know-about-st-catherine-s-monastery-in-egypt-s-sinai

World Heritage Watch, Press Release, December 18, 2024. https://world-heritage-watch.org.

Egypt Today Staff, “A close look at Egypt’s Great Transfiguration Project in Saint Catherine,” Egypt Today, August 31, 2024. https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/1/134461/A-close-look-at-Egypt%E2%80%99s-Great-Transfiguration-Project-in-St

Al-Ahram Weekly, “St Catherine’s future guaranteed,” Al-Ahram Weekly, June 5, 2025. https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/50/1201/547449/AlAhram-Weekly/Egypt/St-Catherine%E2%80%99s-future-guaranteed.aspx

MEE Correspondent, “Egypt: South Sinai’s Saint Catherine ‘destroyed’ by new development project,” Middle East Eye, March 8, 2022. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/egypt-south-sinai-saint-catherine-destroyed-development

State Information Service, “‘Great Transfiguration’ site is Egypt’s gift to entire world, all religions,” State Information Service, March 10, 2024. https://sis.gov.eg/Story/191984

UNESCO State of Conservation Report, 2023. https://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/1443

UNESCO 2002 Inscription Statement, Saint Catherine Area. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/954

The Washington Times, “U.S. Christian leaders sound alarm: Egypt’s megaproject threatens ancient Saint Catherine’s Monastery,” May 2025. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2025/may/30/us-christian-leaders-sound-alarm-egypts-megaprojec/

Korea Times, “Egypt’s candidate for UNESCO director-general pledges renewal through unity and innovation,” Korea Times, May 30, 2025. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/foreignaffairs/20250530/egypts-candidate-for-unesco-director-general-pledges-renewal-through-unity-and-innovation.

Dean Kalimniou, “Explained: The legal battle over Saint Catherine’s Monastery property in Egypt,” The Greek Herald, June 6, 2025, https://greekherald.com.au/community/church/explained-the-legal-battle-over-saint-catherines-monastery-property-in-egypt/.

Saint Catherine's Monastery, Sinai, Egypt, photo Berthold Werner, 9 November 2010, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

Saint Catherine's Monastery, Sinai, Egypt, photo Berthold Werner, 9 November 2010, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.