Dr. Werner Burger’s two-volume book Ch’ing Cash, makes the case that the decline of China’s Qing dynasty was not caused by the draining of silver through the opium trade, but by a complete lack of understanding in the Qing administration of how monetary systems should be managed. Dr. Burger’s extraordinary and meticulous research has spanned fifty years, he has had unprecedented access to the raw materials for his study in the form of a personal collection of seven tons of Qing dynasty cash coins, stored in a 5,000 square-foot warehouse in Hong Kong, and during his research, there was a fortuitous discovery of a hidden room in the First Historical Archives in Beijing’s Forbidden City, containing millions of Qing dynasty documents. Yet the most remarkable element within this story is Dr. Burger’s drive and dedication to a project whose results have stunned scholars of Chinese history.

Edith Terry’s South China Morning Post Magazine article, Coin stash that puts new spin on China’s 100 years of humiliation, describes how the young Werner Burger’s interest in Chinese numismatics – the study of Chinese coins, banknotes, and medals – began in his youth in Germany, around 1950, when a teacher took him to a visiting exhibition of Chinese paintings. He says that his fascination with the paintings, and his frustration that no one could tell him what the calligraphy meant, spurred his interest in all things Chinese.

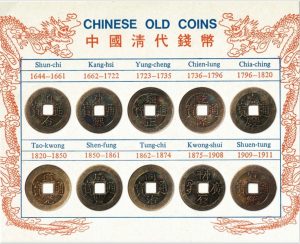

Chinese bronze coins-[foto paul b. toman], By Plismo (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

The foundation of Burger’s researches were actual Qing coins that he acquired from a scrap metal dealer in Hong Kong who became a friend. The dealer imported metal from Indonesia, where Qing coins had remained in use until the 1940s; he provided Burger with 70 bags of coins, almost all Qing period, weighing almost 250 lbs. each.

Burger had intended to study the numismatics of the whole Qing dynasty through the process of comparing coins, known as cash, to historical records. But he was missing documentation from the Qianlong Emperor’s reign (1711 – 1799). The documents should have been in the First Historical Archives in Beijing’s Forbidden City – but they could not be found. Then, in 1996, during a much needed renovation to the dilapidated building, a hidden room was found that contained literally millions of documents from the Qing dynasty. Within these millions of documents, sorted by dozens of dedicated scholars, Burger found the mint records from the Qianlong Emperor’s reign that he was looking for.

For the next twenty years, Burger continued with his work of comparing coins to records stored on tens of thousands of mint records and almost 3000 previously unknown scrolls from the Grand Secretariat of Money Matters, analyzing the information, then writing Ch’ing Cash. His method was to arrange Qing coins by mint and year-produced, for all the years of the dynasty from 1636 – 1911, and then, with the discovery of the hidden archives, to compare them with the mints’ records, revealing the economic detail that eventually explained the Chinese economy’s decline.

Edith Terry states that, “The devaluation of China’s currency through the course of the 19th century is a known cause of the weakness that led to dynastic collapse and the cession of Hong Kong to the British. However, before Burger, the mechanics behind the devaluation were unclear.” Burger summed up the results of his researches, “The old cliché, that the British trade in opium depleted the Qing treasury of silver, leading to its downfall, is not true. It was instead mismanagement of the monetary system, with roots long before the mid-19th century.”

The Qing dynasty had operated with an effective silver-standard that remained stable for the first 80 years of its reign. 925 cash coins equaled a tael of silver (equal to roughly 40g). In a climate of economic stability, when individuals were paid in cash, they knew how much silver each coin or string represented; there was little inflation and the cost of goods remained relatively stable.

Chinese Cash Strings

Chinese coin sampler.

The devaluation of the cash began with the production of numerous forgeries by loyalists of the Ming dynasty in Vietnam toward the end of Qianlong’s reign. The government responded by ordering the forgeries to be bought up, reestablishing economic stability for a time.

However, forgeries continued to leak into the monetary system. Production of authentic mint coins also dropped from about 18 per person per year to .5 to 1 cash per person per year. By 1850 the exchange rate for a tael of silver was over 2,000 cash throughout China. “The continuing disintegration of the monetary system was a factor contributing to China’s losses against foreign powers.” Terry says, a reference to what many call the Century of Humiliation, a period marked by both internal and external conflict in the form of war and rebellion.

The Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) was the most destructive of these conflicts, in which 20-30 million lives were lost in a civil war between the Qing dynasty and a violent Chinese Christian millennial movement. “It was the largest disaster of the Qing dynasty, all because they didn’t take care of the money,” said Burger.

Burger cites the lack of a more developed economic theory for the eventual decline in the Qing dynasty. The notion of paper money as a silver equivalent was rejected. “The officials had only studied the Confucian classics and had no idea about money.” He compares the development of economics in the Qing dynasty to economic development in Europe; “What one can learn from how the Qing dynasty ran its show is that, although they were good book keepers – much better than the British or the Germans – they did a lousy job of making a system of their economy. The Europeans very soon had Adam Smith and, by writing down the theory and challenging it, slowly they had the economy in their grip. The Chinese never did. They had no theory.”

Now 82, Dr. Werner Burger is planning his next numismatics project, a studies center for Chinese numismatics at the University of Hong Kong (HKU), which has accepted the proposal. He plans work in collaboration with Dr. Florian Knothe, director of the University Museum and Art Gallery at HKU, who also assisted him with Ch’ing Cash. Burger hopes to fund this project and to make HKU one of the primary research centers for world coinage, through the sale of his collection of two million documented coins to a donor to the university. Terry’s article quotes another great scholar of Chinese coins, Dr. Lyce Jankowsky of Paris-Diderot University, who says this collection would bring HKU into the front line of all coin collections in the world.

Hong Kong, China: Middle Island between Deep Water Bay (foreground) and Repulse Bay (background left) and Middle Bay (background middle), photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas, via Wikimedia Commons

Hong Kong, China: Middle Island between Deep Water Bay (foreground) and Repulse Bay (background left) and Middle Bay (background middle), photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas, via Wikimedia Commons