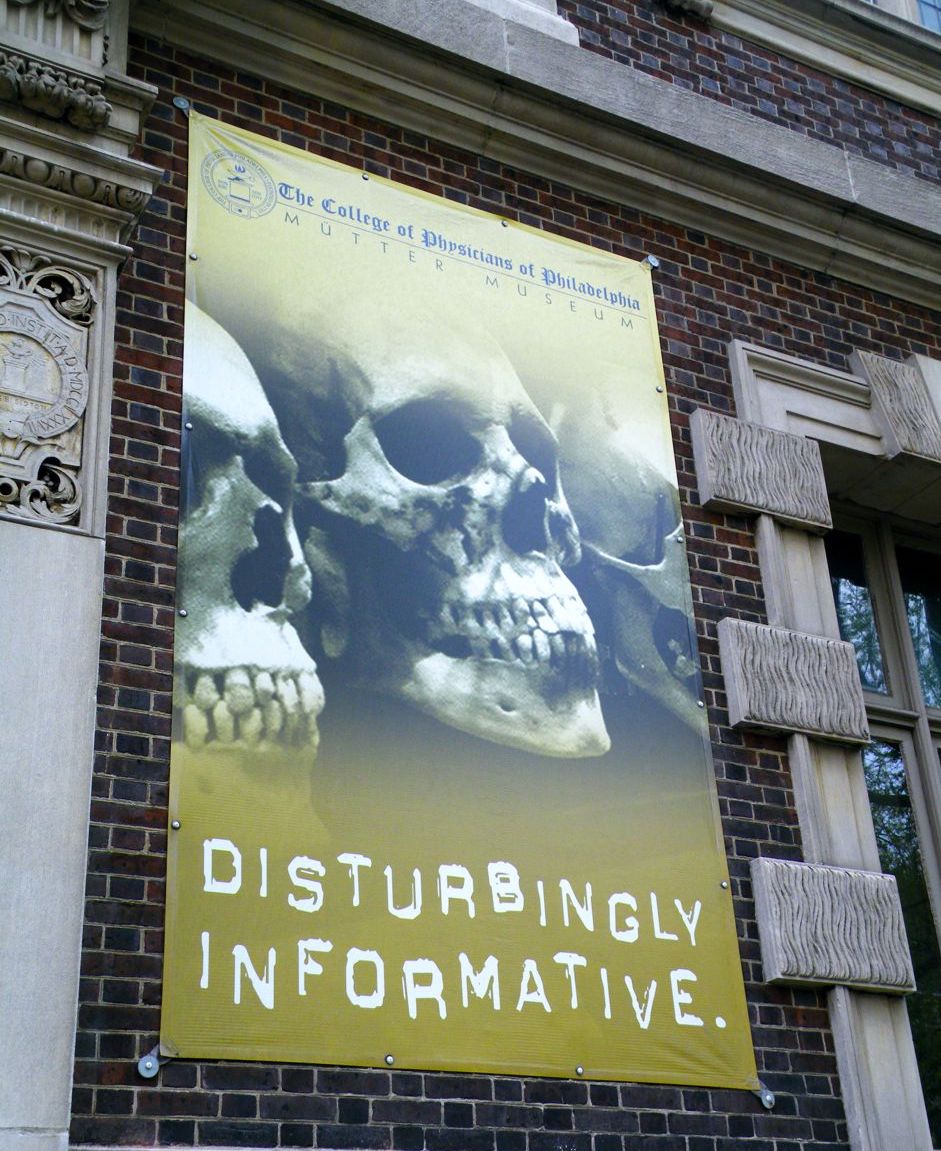

College of Physicians of Philadelphia exterior, Courtesy The Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

Former staff and supporters of the outstandingly quirky Mütter Museum in Philadelphia are raising concerns about its future, saying that an overzealous director and CEO are attempting to change its unique character by sanitizing controversial exhibits and removing online videos from public view.

The Mütter Museum, considered the finest museum of medical history in the United States, was founded in 1849 as part of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.[1] It is a public museum as well as a teaching and research resource for medical scientists and historians. Its collections include anatomical and pathological specimens of medical interest going back more than 100 years. You have to be pretty special to rate a place in the museum. The museum’s former director, Gretchen Worden, once said that while she hoped to become an exhibit herself when she died, she’d have to get a very rare disease in order to justify it. Worden helped to bring the Mütter Museum into the public eye, turning it from an obscure physicians-only research facility into a beloved public institution with annual attendance exceeding 130,000 visitors.

Mütter Museum visitors. Courtesy The Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The museum’s 2013 “Save our Skulls” campaign sought donations of $200 to adopt a skull, which would pay for repairs and new mounts. The successful campaign for preservation also gave the public a direct link and encouraged repeat visits.

The recent changes to the Mütter’s policies were initially said to be in response to complaints by local media that there had been improper delays in repatriation of the museum’s few Native American human remains (which were not displayed), something that all sides agreed should be speedily done.

However, Dr. Mira Irons, the College of Physicians new CEO, and the Mütter Museum’s new executive director Kate Quinn have gone far beyond repatriation issues in altering the museum’s public presence. Most of the museum’s online YouTube channel videos (100,000 subscribers) and all its online images of human remains have been removed. A statement signed by Irons and Quinn on the museum’s website says the removals are temporary and that many will return after review to determine that “they meet best practices on the respectful exhibition of human remains.” Quinn’s position has been that the collections involved people who were no longer living, and some had not clearly consented to be included in it; Irons’ that the museum needed to be “respectful and appropriate.”

The concerns over informed consent and respectful presentation appear to be more about the administrators’ personal sense of what is right and proper, not what the museum’s researchers, the public, and online visitors want to see. Protesters against the changes argue that there is nothing inherently disrespectful or unethical in the presentation of skeletons with medical anomalies or organs in jars. Furthermore, the museum documents a history of medicine and by necessity, many of its exhibits came from people who died long before notions of medical ‘consent’ existed.

Papier-maché eyeball model, late 19th c., Courtesy The Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

The Mütter Museum Preservation Society, @protectmuttermuseum, which has opposed some of the recent changes, says:

“Our contention has never been that the Museum is perfect. We do believe that its mission is important. That teaching & displaying and honoring human remains is paramount to the understanding of the human condition. That these remains deserve dignity & appreciation, not scorn & concealment. If the leadership at the @MutterMuseum & @CollegeofPhys wanted to have frank, open discussions & involve members of affected communities, that’s what they should do. Unfortunately, that’s not their plan. They are making sweeping, judgmental, reactive moves without input from anyone but their own elitist echo chamber. And THAT is what we are protecting against.”

Certainly, staff have left the Mütter Museum at an unprecedented rate; the museum lost ten of its 50 employees in the last year. While CEO Irons says that is ordinary turnover, departing staff have referred to a toxic environment in which the very purpose of the museum has been challenged.

A former director and senior consulting scholar who recently resigned in protest, Robert Hicks, says the museum is being deconstructed. He insists that the Mütter has always been very concerned with the ethical presentation of its collections:

“One ethos that the museum has been very strong about is: there’s no division between what constitutes a normal body and an abnormal one. There’s a continuum of phenomena, but we’re all normal. A person who has terminal cancer is still a normal human being.”[2]

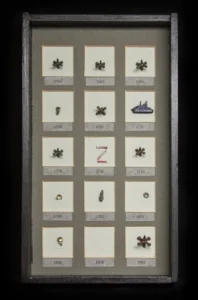

Medical instruments, Mütter Museum, Courtesy The Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

Hicks noted that a donor, Carol Orzel, whose suffered from a very rare condition in which muscles and tendons are gradually transformed into bone,[3] was committed to visiting medical schools – not only so that physicians in training could better treat the condition, but also so that they understood that she was a fully autonomous human being as well as being disabled. On her death, Carol donated her skeleton to the museum for display (together with her collection of costume jewelry, which is also displayed at her wish).

By filleting out the personal in favor of an abstract ‘ethical’ standard, the museum may also compromise its value as a medical resource for future physicians. One now-missing video featured donor Robert Pendarvis, who gave his original heart to the museum after a rare condition called acromegaly required a heart transplant in 2020. He expressed disappointment that this medical information was no longer available to his own doctors as a result of the removal. Pendarvis said that he also had planned to give his skeleton on his death, “because of the acromegaly[4] information that they have at the museum. That was what was important.”

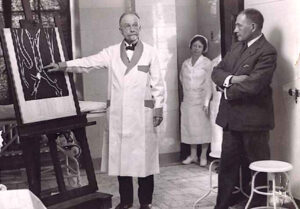

Dr. Chevalier Quixote Jackson demonstrating the removal of objects.

Some objects at the Mütter Museum are historical specimens, primarily of interest because of who they belonged to – a tumor from President Grover Cleveland’s jaw and the brain of Charles Guiteau, assassin of President James Garfield. Most exhibits, however, display the special medical attributes of anonymous, ordinary people. They may show how medical conditions have been analyzed and understood over time, or the early evolution of medical treatments. Often, exhibits are the opposite of high-tech, like the exhibit of 2,000+ objects removed from the throats and lungs of mostly very young patients by Dr. Chevalier Quixote Jackson (1865 – 1958) a renowned Philadelphia otolaryngologist and Fellow of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia who developed novel techniques and tools to keep babies from choking on small objects.

While at times veering into the grisly, the Mütter Museum’s exhibits are the opposite of a carnival display. The reason that so many are deeply moving is precisely because of the very real picture they show of medical practice on human beings at different times. The museum’s exhibits are about the very special humans whose physical attributes have something to teach physicians – and us all. The focus is not on the abnormal but rather on how broad the category of “human” can be.

Note: The Mütter Museum’s press website has a page listing preferred and non-preferred descriptive terms to be used in press reporting. We checked, and it turns out that we abided by these preferences without even trying. Thanks to the Mütter Museum for providing many of the photographs for this article.

Swallowed Objects from the Chevalier Jackson Collection, College of Physicians of Philadelphia https://www.cppdigitallibrary.org

[1] “The College of Physicians of Philadelphia was founded in 1787 by a group of physicians including Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of our nation’s Declaration of Independence. The College is a not-for-profit educational and cultural institution, with the mission of advancing the cause of health while upholding the ideals and heritage of medicine.” College of Physicians of Philadelphia, https://muttermuseum.org.

[2] Alan Yu, Why did the Mütter Museum take down all their YouTube videos and online exhibits? WHYY, May 13, 2023, https://whyy.org/articles/philadelphia-mutter-museum-online-exhibits-taken-down-why/

[3] Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). See https://www.pennmedicine.org/for-patients-and-visitors/patient-information/conditions-treated-a-to-z/fibrodysplasia-ossificans-progressiva-fop#:~:

[4] Acromegaly. See Pituitary. 2009 Sep; 12(3): 236–244, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2712620/

Mütter Museum, exterior, detail, photo Jim R Rogers, April 20, 2009, CCA-SA 2.0

Mütter Museum, exterior, detail, photo Jim R Rogers, April 20, 2009, CCA-SA 2.0