Not all ancient Egyptian mysteries are quite so ancient.

Two stories, crediting different discoverers, are told about how the trove of papers found in the Grand Temple of Seti I were discovered.

The first version is that in 2012, a graduate student named Mohamed Abul-Yazid found thousands of archival documents from the Egyptian Antiquities Service while exploring “the Slaughterhouse,” a room in the temple thought to have been used for animal sacrifice.

According to the second version, an inspector named Ayman Damarany stumbled across the documents while on assignment photographing the “Slaughterhouse” wall paintings in the Grand Temple of Seti I in 2013.

What is not clear is why thousands of documents, covering a hundred years of excavation, were left in a dark, closed-off room in an ancient temple in the first place. And then forgotten.

For whatever reason they were left there, and whether it was Mohamed Abul-Yazid or Ayman Damarany who discovered the lost hoard of correspondence, excavation reports, maps and surveys from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, the discovery has outstanding historical value. Even a cursory assessment reveals that the papers are essential for understanding how one of Egypt’s most important sites, the Abydos temple, was explored and its secrets revealed.

The papers’ twenty-first century rediscovery provided the impetus for an archival digitization project dubbed “The Abydos Temple Paper Archive.” The project is a collaborative mission between Egypt’s Ministry of State for Antiquities and the University of California, Berkeley. Support for the project is through the American Research Center in Egypt’s (ARCE) Antiquities Endowment Fund.

Egypt and its monuments, 1908, photo by Robert Smythe Hichens, 1864-1950, Library of Congress, Wikipedia Commons.

Serious study of the documents began in April 2017; the initial phase lasted for three months. A thirteen-member team of Egyptologists, administrators, archeologists, conservators, and photographers (including Mohamed Abul-Yazid and Ayman Damarany) organized the loose documents and developed a system for recording, processing, conserving and translating them. Most of the documents are in Arabic, some are in English, and a few are in French and German. They were first transcribed into a digital, searchable database then translated – Arabic documents to English, and English, French and German documents to Arabic. By the end of June 2017, over 400 documents had been processed and entered into the digital archive.

The discovery of the documents had particular significance because, as the team noted, “… for the first time, the early history of Egyptology could be examined from the viewpoint of the Egyptians who worked at and managed the ancient sites over much of its modern history, rather than through the lens of foreign missions. “

There are records demonstrating how sites were managed, researched, documented and protected over time. They show official correspondence in response to political change and unrest. Some records even show the confiscation of stolen artifacts and the permitted sale of others, a practice that was legal under twentieth century Egyptian regulations lasting until 1983.

There are many more documents to be processed after the initial selection. Among those that have already garnered attention are the inspection reports of Egyptologist Dorothy Eady, dating to 1968-1969. The eccentric Ms. Eady, known as “Omm Seti”, believed herself to be the reincarnation of a priestess of the Abydos Temple and a secret lover of Seti I. Eady’s life was later a source for popular publications such as the 1987 The Search for Omm Sety, A Story of Eternal Love, by Jonathan Cott with Hanny El Zeini. According to John Anthony West’s book review in the New York Times, She had her Life to Live Over, Eady was respected, sometimes grudgingly, in archeological circles because, “ …she kept on making Egyptological discoveries based on what she insisted was memory, not research or mere intuition. According to West, when Eady said: ”Dig here. I remember the ancient garden was here,” they dug and found . . . the ancient garden.”

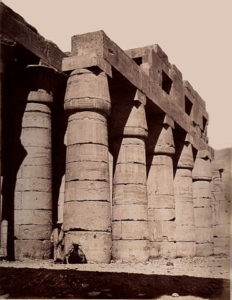

Felice Beato (1834-1907) – An Ancient Egyptian temple. Wikipedia Commons.

Writings and documents from other famous contributors to Egyptology, such as Labib Habachi, were also found and will be digitally archived during the project.

The development of the Abydos Temple Paper Archive is timely, as Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi is promoting tourism of all types, especially cultural tourism. According to an article on April 2, 2018 in Egypt Today, “Sisi called on officials to carry on developing tourist attractions, using the most modern methods to preserve Egyptian antiquities, including storing them in proper places.”

Though it will take many seasons of work to complete the digital archive, sixty pages of it have already merited a temporary exhibit in the Sohag National Museum. The much-delayed opening of the museum in August 2018, after twenty-nine years of bureaucratic delays, is representative of the Egyptian government’s focus on reviving foreign tourism, which has dropped significantly in the last decade.

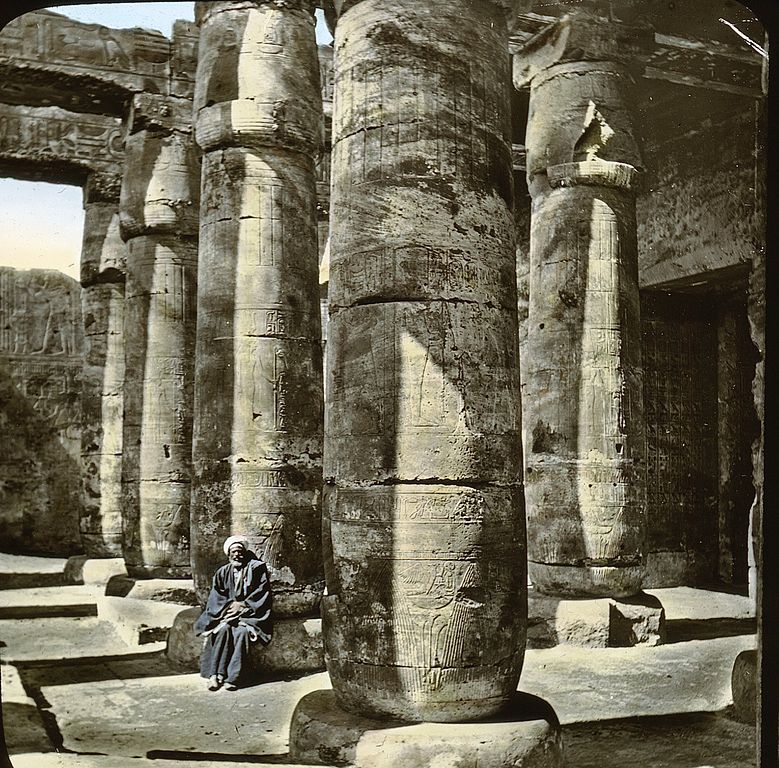

Abydos, Egypt. Lantern slide, 3.25 x 4 in. Brooklyn Museum, Goodyear Archival Collection. Brooklyn Museum, S03i2367l01.jpg

Abydos, Egypt. Lantern slide, 3.25 x 4 in. Brooklyn Museum, Goodyear Archival Collection. Brooklyn Museum, S03i2367l01.jpg