One hundred fifty years ago, students of art history learned through engravings and often heavy-handed reproductions and plaster casts of iconic works. Few could afford to travel to see original world masterpieces. Today’s technologically sophisticated replicas can be perfect copies, so far as the human eye can tell. But how does the lack of authenticity or of context influence our understanding and experience of historical artworks? Does using these reproductions open new avenues for appreciation or compromise the emotional resonance and sense of connecting to human history that we feel in the presence of the originals? Or both?

There is social and historical meaning even in familiar contexts that are not original – for example in Greek sculptures brought to Rome to meet Imperial tastes 2000 years ago. Is Britain’s competition with Napoleon for the Parthenon Marbles more meaningful when viewing them in the British Museum? How do our brains “see” authenticity? Do even “perfect” reproductions lose something in translation?

Plaster cast after Michelangelo Buonarroti, Medici Madonna. Original made ca. 1526–1532, cast in 1897. Photo: SMK, National Gallery of Denmark.

The National Gallery of Denmark (SMK) is challenging traditional notions of art authenticity with its upcoming Michelangelo exhibition. Opening March 29 and running through August 31, 2025, the show will juxtapose 19th-century plaster casts with cutting-edge 3D-printed replicas, bringing together works that are otherwise immobile or scattered across the globe. These reproductions, including Michelangelo’s David and the Medici Madonna, aim to give visitors access to pieces that must remain in their original contexts. The exhibition also includes original drawings by Michelangelo, models and correspondence about the works.

Matthias Wivel, the exhibition’s curator, sees today’s exact copies as a continuation of the tradition of learning about art through reproductions. “Used responsibly,” he says,”they have enormous potential and value.” Wivel acknowledges the experimental nature of the exhibition, viewing it as a chance to debate the role of replicas in art appreciation. He notes that utilizing replicas has enabled the museum to bring together different kinds of materials to enhance the understanding of original artworks. Using reproductions, the exhibition will reunite pieces originally created for the tomb of Julius II, now dispersed across Europe, such as the Boboli Prisoners in Florence and Rachel and Leah in Rome.

Factum Arte, the most technologically sophisticated company documenting and reproducing artworks today, collaborated with SMK to enhance its collection. Their replicas are so precise that they capture details down to the micron level, offering unparalleled fidelity in color, texture, and even marble veining. The company can also use earlier documentation to reconstruct the condition of artworks later damaged.

Another example in the show is the recreation of the Infant John the Baptist by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence in 1996, using archival photos taken before its destruction in the Spanish Civil War, when it was smashed with hammers and its head burnt. The work is presented with scars still visible. One of the many questions posed by the exhibition is – how has its destruction also become part of its history?

Plaster casts – ‘civilizing’ the public since Roman times.

In ancient Greece and Rome, plaster was used for a variety of purposes: for death masks, copying sculptures and as a sculptural medium in its own right. Pliny the Elder credited Lysistratus with inventing the casting technique in antiquity. Casting impressions were used to create clay models, which then could be used to make bronzes – or as the basis for new marble sculptures.

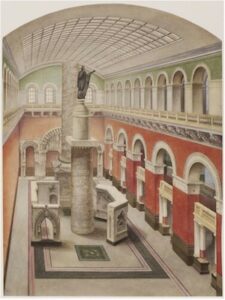

The Cast Courts, Room 46a, Victoria and Albert Museum, London. About 1873, © Victoria and Albert Museum.

The earliest art academies in Renaissance Italy employed plaster casts as teaching tools. French academies collected numerous plaster casts in the 1800s, a practice later emulated in Germany. The plaster casts were used both for studying classical art and for honing artistic techniques. Plaster casts were exported to the Americas in order to spread the influence of European art traditions. They became important tools and exhibits in museums in Mexico City, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, where there relatively low cost in comparison to original works of art enabled their acquisition, even in bulk, and museums built large collections of such plaster sculptures. In Britain, plaster casts were used in projects to educate the working public – including circulation of copies of the Parthenon Marbles. In 1867, Henry Cole established an International Exchange Scheme, a project aimed to promote art by facilitating the exchange of reproductions across Europe. The scheme was signed by 15 European rulers, showing how widely the use of the casts was appreciated at the time.

The current perspective on the exhibition and conservation of plaster casts varies widely across museums and institutions. Some museums, like NY’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, have opted to divest portions of their cast collections by selling or transferring them to other institutions. Others have invested in the redisplay and curation of plaster casts.

For example, the New Acropolis Museum and its Underground exhibit highlight the integration of plaster casts into contemporary museum spaces. The refurbished Galeries de Moulages at the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine in Paris celebrate its historic plaster cast collections. The Cast Courts at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London have been extensively refurbished, demonstrating a commitment to maintaining and enhancing the visibility of plaster casts in museums.

By the twentieth century, many museums relegated plaster casts to secondary status. Some were worried about the potential for casts to be misinterpreted as originals by viewers. For others, plaster casts lacked what Walter Benjamin called the “aura” or the unique presence of objects, and the fact that the casts had no real connection to the work of the original artists. This Danish exhibition argues for a rethinking of the possibilities of a whole range of reproductive technologies for art – and treating the replica as an object in its own right.

Head of David, Plaster cast after Michelangelo Buonarroti. Original made in 1501-1503, cast in 1890. Photo: SMK, National Gallery of Denmark.

Head of David, Plaster cast after Michelangelo Buonarroti. Original made in 1501-1503, cast in 1890. Photo: SMK, National Gallery of Denmark.