The EU Regulation 2019/880, which severely limits the import of ancient art, manuscripts and antiques into the European Union became law in 2019. When EU Regulation 2019/880 is fully implemented through a unified digital import application system in all countries, sometime between 2023 and 2024, it will likely act as a de facto ban on import of antiquities into the twenty-seven current EU nations.[1]

Draft Implementing Regulation and Rules Issued in Late March 2021

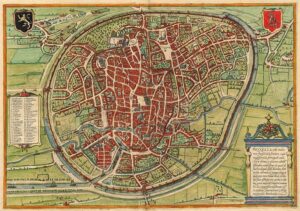

Antique map of Brussels, copper engraving, Bruxella, Urbs Aulicorum Frequentia, Fontium Copia, Magnificentia Principalis Aulae, Braun & Hogenberg, 1576. From: Beschreibung und Contrafactur der Vornembster Stät der Welt. Liber Primus. Köln, 1572. Public domain.

The Draft Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) and Annexes to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) were issued in late March 2021. These are the proposed rules implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/880 of the European Parliament and of the Council. In 45 pages of rules and recitals, the draft provisions outlined the rules and documentation that will be required for importing ‘cultural goods’, meaning art and antiquities into the EU.

Despite the lack of any evidence that the EU legislation is necessary to combat looting in unstable or war-torn countries, supporters in Parliament, among archaeological organizations and anti-trade activists have continued to argue that the art trade supports terrorism. This canard is reiterated in the proposed implementing regulations.

The EU requested comments on the implementing regulations via its “have your say” website. Despite the rules’ complexity, only a 4-week period for public comment was allowed. The majority of the 50+ submitted comments were critical of the proposed rules, many finding that they threatened the future circulation of art throughout the EU and would prove devastating to the art market and thence to collectors and museums.

Submissions came from a wide range of organizations. The IADAA stated that the regulations were not in line with international law, that they were disproportionately burdensome, that regulations were not evidence based and were intended to address a problem of terrorist funding that didn’t actually exist.[2] It noted that the cost and delay caused by the proposed implementing regulations will damage the legitimate art and antique markets, which contribute significantly to the EU economy, and provide employment for hundreds of thousands of people.

Comments were submitted by the Antiquities Dealers’ Association (UK), British Antique Dealers’ Association, the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art, SNA, Syndicat National des Antiquaires, the European Art Market Coalition (EAMC), International Association of Professional Numismatists(IAPN), Global Heritage Alliance, The British Antique Dealers’ Association, Ancient Coin Collectors Guild, and international art market analyst Ivan Macquisten and others. All are available at the EU’s Have Your Say website, although tracking them is made more difficult by the system, which often enters an organization’s comments as “anonymous.” While acknowledging the importance of halting trade in looted objects, the submissions criticized the regulatory process and made suggestions for clarifications and amendments to the proposed regulations.

One of the fullest responses was submitted by CINOA, the umbrella organization representing some 5,000 art and antique dealers. The CINOA Position paper questioned the legality of certain rules and characterized the rules and the processes for import as “unnecessarily complicated, burdensome, and disproportionate for the majority of ordinary cultural goods that are traded legally and unworkable unless modified.”[3]

Regulation 2019/880 Impacts the following goods.

For the reader who is not familiar with the underlying legislation Regulation 2019/880 to which the draft implementing rules apply – it will restrict import and export of items over 250 years of age into the EU. For ancient art and “archaeological” materials, Regulation 2019/880 requires either documentation of lawful export from the source country (although the majority of countries have no such permitting regimes) or in exceptional cases, if the source country cannot be determined, the exporter must provide documentation from a second country in which the object has been for at least five years. For other categories of art, it requires a sworn affidavit from the exporter that the item meets the same criteria. A key concern regarding the affidavit system is that the importer may have no way to know if that is true or not, since cultural items may have circulated for decades among multiple owners.

‘Article 4’ Items Requiring Proof of Legal Export from Source Countries to Obtain Import Licenses are:

1710 De La Feuille Map of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg – by Daniel de la Feuille. The main map is surrounded by seventeen plans and views of major cities in the region. It was originally prepared for inclusion as chart no. 27 in the 1710 edition of De la Feuille’s Atlas Portatif. Public domain.

(1) products of archaeological excavations (including regular and clandestine) or of archaeological discoveries on land or underwater, (2) elements of artistic or historical monuments or archaeological sites which have been dismembered, and (3) liturgical icons and statues. Effectively, the Article 4 requirements for import licenses could apply to all antiquities including most ancient coins.

‘Article 5’ Items Requiring a Sworn Affidavit for Entry include:

- rare collections and specimens of fauna, flora, minerals and anatomy, and objects of palaeontological interest

- property relating to history, including the history of science and technology and military and social history, to the life of national leaders, thinkers, scientists and artists and to events of national importance;

- antiquities, such as inscriptions, coins and engraved seals;

- objects of ethnological interest;

- objects of artistic interest, such as:

- pictures, paintings and drawings produced entirely by hand on any support and in any material (excluding industrial designs and manufactured articles decorated by hand);

- original engravings, prints and lithographs;

- original works of statuary art and sculpture in any material;

- original artistic assemblages and montages in any material;

- rare manuscripts and incunabula;

- old books, documents and publications of special interest (historical, artistic, scientific, literary, etc.) singly or in collections

The businesses likely to be hit hardest by the regulations are the legitimate traders, auction houses and small galleries dealing in art and collectibles in major art centers. These businesses are already subject to regulations on import and export transactions, banking, and tax collection under national laws. The U.S., E.U. and U.K. together dominate the approximately $800 billion annual arts industry and trade among these nations is very active, with the majority of the objects having been in circulation for decades.

The Committee for Cultural Policy also submitted commentary on the draft implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/880. We find serious fault with the proposed regulations, which we believe will threaten the most active art exchanges in the world – those between the United States and the EU and the UK and the EU, while doing little to stem illicit trafficking and having no effect whatsoever on terrorist financing through art.

Submission of the Committee for Cultural Policy

Comments submitted on the draft implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/880 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the introduction and the import of cultural goods into the European Union

Date April 21, 2021

The Committee for Cultural Policy (CCP) is a United States non-profit organization providing research and analysis of public policy issues related to art and cultural property.[4] We appreciate the opportunity to respond to the European Commission’s request for feedback on its draft implementing regulation listed as Ares (2021)2087089 and Annex – Ares (2021)2087089.

CCP supports policies that enable the lawful collection, exhibition, and global circulation of artworks and preserve artifacts and archaeological sites through funding for site protection. CCP deplores the destruction of archaeological sites and monuments and encourages policies enabling safe harbor in international museums for at-risk objects from countries in crisis.

CCP believes that communication through artistic exchange is beneficial for international understanding and that the protection and preservation of art is the responsibility and duty of all humankind.

Based upon our extensive research into cultural property law and the licit and illicit trade in antiquities, these proposed regulations will not be in any way effective in achieving Regulation (EU) 2019/880’s goal of “the prevention of terrorist financing and money laundering through the sale of pillaged cultural goods to buyers in the Union.” The Regulation (EU) 2019/880 will not be effective in halting any significant terrorist financing, since there is no evidence supporting the claim that it exists. Such claims have been widely debunked.[5] Instead, the regulations threaten to curtail the circulation of lawfully acquired art and artifacts through burdensome and excessive regulation. We believe that implementation of Regulation (EU) 2019/880 will in the end be detrimental to the interests of the public and to academic institutions and museums that will be denied the ability to acquire original works for study and exhibition.

We have the following concerns regarding the proposed rules implementing the Import of Cultural Goods (ICG) Regulation (EU) 2019/880:

I.

We find that several of the proposed regulations are poorly written and conceived. Many of the terms used in the rules are insufficiently or incorrectly defined or not defined at all. The proposed regulations lack definitions of key words and terms such as “of importance”, “licit provenance”, “provenance”, and “country of export,” creating confusion and making compliance difficult and uncertain.

1904 Kisaburō Ohara Satirical Octopus Map of Asia and Europe 1904 Japanese satirical map – A Humorous Diplomatic Atlas of Europe and Asia. Public domain.

There are significant uncertainties and ambiguities regarding the administration of Articles 1(3) and 8(1) in the draft Implementing Regulation:

Article 1(3): ‘country of interest’ means the third country where the cultural good to be imported was created or discovered or the last country where the cultural good was located for a period of more than five years for purposes other than temporary use, transit, reexport or transhipment, ‘in accordance with Articles 4(4) and 5(2) of Regulation (EU) 2019/880’;

And

Article 8(1): The applicant shall provide evidence to the competent authority that the cultural good in question has been exported from the country of interest in accordance with its laws and regulations or shall provide evidence of the absence of such laws and regulations at the time the cultural good was taken out of its territory.

Article 4(4) and 5(2) of Regulation (EU) 2019/880 provides an exclusion for cultural goods that have been in a third country for a minimum of five years AND

(a) the country where the cultural goods were created or discovered cannot be reliably determined; or

(b) the cultural goods were taken out of the country where they were created or discovered before 24 April 1972.

Note that Regulation (EU) 2019/880 of 17 April 2019 does not define or utilize the term “country of interest” anywhere.

Instead of taking the reasonable step of requiring proof that art or artifacts have been in a third country for five years, the draft regulations exclude objects held in the United States or another country with comparably strict import rules even if they had been in that country for 25, 35, or even 45 years – if the country of origin “could be reliably determined.”

If the above limitations under (a) and (b) of Article 4(4) are required to be met, then Article 8(1) of the draft regulations does not make clear how and by whom it will be decided that “the country where the cultural goods were created or discovered cannot be reliably determined.”

1593 map of Northern Europe by Gerard de Jode. Public domain.

This creates a standard in which objects with a history of extensive trade in ancient times that could be “discovered” in a third country, or objects very similar to those found in other countries, would be required to show a 5-year stay in another country without export restrictions, such as the United States, in order to be imported lawfully into the EU, while other objects not widely in trade could not.

While proof of a 5-year stay in the U.S. for import into the EU is eminently reasonable and wholly supported by the Committee for Cultural Policy, this regulation also appears to establish two classes of objects, where the country of origin either can or cannot be reliably determined based upon current knowledge about ancient trade or on subtle visual similarities or on fluctuating modern borders. None of this is easy to determine, even for an expert.

Customs officials are not trained to resolve sophisticated art historical questions which cannot be reliably determined even by art experts. Examples of objects for which “the country where the cultural goods were created or discovered cannot be reliably determined” could include:

- most minor objects from countries with formerly Greek or Hellenistic cultures from around the Mediterranean

- many early Islamic ceramics, wood and metalworks from Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and parts of Western China

- virtually all Ottoman period metalworks manufactured and circulating in trade throughout the Ottoman Empire

- All ancient Chinese ceramics utilized in trade

- Pre-Columbian ceramics and textiles from Peru/Bolivia

- Pre-Columbian artifacts from Central American nations where past civilization extended over multiple modern borders.

- Thai, Vietnamese or Cambodian artworks

- Tibetan or Nepalese sculpture

- Many Pre-Partition objects from India or Pakistan

- Virtually all ancient coins

- Virtually all ancient beads

This list is only partial.

its This policy potentially creates a two-tier system that has nothing to do with the intent of the Regulation. It means that having no knowledge of the actual findspot of an object will make it easier to import into the EU so long as it has been out of the country of origin for 5 years. Having more information will make it harder. The same regulations will make entry impossible for objects with an identifiable site provenance to a specific country that has been out of it for 45 years but which has lost its past documentation of lawful export. This is not only illogical, it is contrary to all academic principles in which correct information on provenance is desirable and has scholarly value.

II.

The requirements for proof of lawful export are unreasonable and burdensome. They are impossible to meet for the vast majority of lawfully owned goods in circulation worldwide and will severely limit the circulation of antiquities into the EU.

L’Europe en Ce Moment – Fantaise Politico-Géographique. 1872 Yves and Barret Pictorial Map of Europe after the Franco-Prussian War. Public domain.

Most artifacts and antiquities have circulated in the art market for decades and had numerous owners. This is a powerful reason why importers cannot reasonably attest “under oath” to whether an object left a country of origin lawfully: that information is not available.

The requirement for proof of lawful export is extremely unlikely to be available for antiquities from other countries imported into the United States because proof of lawful export is not required for importation into the United States except in the case of objects listed under an agreement with the source country under the Cultural Property Implementation Act AND which have not been outside of the country of origin for ten years or more.

In fact, well into the 21st century, if a document showing proof of lawful export was presented to U.S. Customs as proof of age or country of origin, they generally refused to accept it, demanding instead a statement made by the importer, in English. The unintended effect of the regulations will be to exclude the artworks longest in circulation from import, for which records of original export, never required for importation into the United States, have long since been discarded.

For example, some of the most widely circulated and popular antiquities in the United States are from Egypt, whose government licensed antiquities sellers and allowed permitted export until 1983.[6] Even when the owners of Egyptian artworks have retained the original paperwork, that paperwork does not sufficiently describe the goods to meet the 2019/880 regulations.

- Too much information is required for issuance of a single export license. The number of photographs required is excessive, far more than is needed to adequately identify the object. The lack of a value threshold for antiquities means that it is economically unfeasible to go through the entry process for low value objects.

- The process for entry of “several cultural goods” is not designed for commonly imported items such as ancient coins, which are often shipped in consignments of hundreds or even thousands. (Art. 6(2)) A coin should not be required to be the “same denomination, material composition and origin” in order to be combined with others in an importer statement. (Art. 11(2))

III.

The regulators have failed to provide necessary information to importers in order to facilitate compliance.

There is no database of laws in all EU languages to identify which countries have export laws and from which date. There is no database showing which countries actually enforced export laws and when they did so. As a result, accurate information on source country laws is not available to importers. Because the majority of antiquities have circulated for decades if not hundreds of years, without provenance documents or record of prior ownership, importers often cannot know when an object left its country of origin and therefore what laws applied at the time.

Article 4(4) of Regulation (EU) 2019/880 requiring holders of goods to provide “evidence of the absence of such laws” not only places the entire burden on the importer, it does so in the absence of information that would enable them to determine how laws on paper were administered. The regulations fail to take into account difference between art source countries’ cultural heritage laws on paper and their administration.[7] This is another reason why importers cannot reasonably attest to whether an object left a country of origin lawfully.

IV.

It is not clear what happens to an object whose application for import is denied. The regulations fail to define procedures and processes to be followed if an application is rejected. Nor is there a procedure for appeal.

The regulations vaguely reference returning objects whose applications are rejected to source countries. This appears to be a serious violation of the importer’s property rights if an incomplete or inadequate application creates a legal assumption that (1) the object is unlawfully owned, (2) EU customs can arbitrarily and without legal evidence make a determination that a specific modern political entity has superior title, (3) that seizure and delivery to a claimant nation is lawful under the law of the EU country of entry, and (4) in cases where religious or minority community artifacts are concerned, that human rights and cultural rights to property enshrined in international instruments can be superseded by an arbitrary decision by a customs official to return religious or minority community objects to a source country that is hostile to that religion or minority community.

The requirement that “Any costs related to an application for an import license shall be borne by the applicant,” is too open ended and given the excessive requirements for documentation, could discourage all trade in lower value objects solely based upon the potential cost of import. (Art. 6(4))

V.

Storage and marking provisions are inadequately defined and may easily result in damage to historical objects, and also engender unnecessary costs for importers of law value items.

Antiquities, even of low value, are fragile. They should receive proper storage protection and they should not be “marked” in a manner that damages them or compromises their integrity.

Conclusion.

The primary effect of the proposed regulations will be to lock lawfully owned antiquities and ancient coins that have circulated in the art market for decades into the countries where they now reside, regardless of whether or not these are the countries of origin.

The significant trade between the United States and the EU in antiques and antiquities will be adversely impacted simply as a result of the United States’ longstanding policies allowing importation of antiquities without requiring proof of lawful export and the consequent lack of documentation available to importers.

At most, importers transferring objects from the United States to the EU should be expected to verify that the object was legally on the market in accordance with U.S. laws and regulations. The U.S. is a major trading partner with strict laws. The EU should make special allowances for objects exported from the United States as a “country of interest,” when the object has been located in the United States for a period of more than five years for purposes other than temporary use, transit, re-export or transhipment.

Respectfully,

Kate Fitz Gibbon

Executive Director, Committee for Cultural Policy

[1] Current EU countries are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Republic of Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden.

[2] IADAA, It is time to ask again for the opinion of the Regulatory Scrutiny Board, April 21, 2021, https://iadaa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/IADAA-have-your-say-contribution-21-04-2021.pdf.

[3] CINOA, 2021 04 20 CINOA submission to the EC Have Your Say consultation on draft Implementing Rules of Import of Cultural Goods, April 20, 2021, https://www.cinoa.org/cinoa/perspectives?action=view&id=G3GXDXkBm0Z39cd18AMF

[4] The Committee for Cultural Policy (CCP) is an educational and policy research organization that supports the preservation and public appreciation of the art of ancient and indigenous cultures. CCP publishes news, opinion, and extensive legal analysis of cultural policy, including The Global Art and Heritage Law Series, a nine-volume, nine-country analysis of global heritage laws available for free download at www.culturalpropertylaw.org. The Committee for Cultural Policy, POB 4881, Santa Fe, NM 87502. www.culturalpropertynews.org, info@culturalpropertynews.org.

[5] See, for example, Matthew Sargent, James V. Marrone, Alexandra Evans, Bilyana Lilly, Erik Nemeth, and Stephen Dalzell, Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open Source Data, 3, 10, Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, California, 2020, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2706.html

[6] Frederik Hagen and Kim Ryholt, The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930, The H.O. Lange Papers, Scientia Danica. Series H, Humanistica, 4 · vol. 8, 2016.

[7] CCP’s publication of The Global Art and Heritage Law Series, prepared by independent legal teams in each of the countries studied, makes clear that while cultural heritage laws have existed for many years in the countries studied on paper, their terms were often ill-defined and they were rarely enforced. Among the countries whose administration of cultural heritage laws were documented were Nigeria, China, Peru, Bulgaria, and India. These countries also had not documented objects or implemented permitting processes that were stipulated under domestic law.

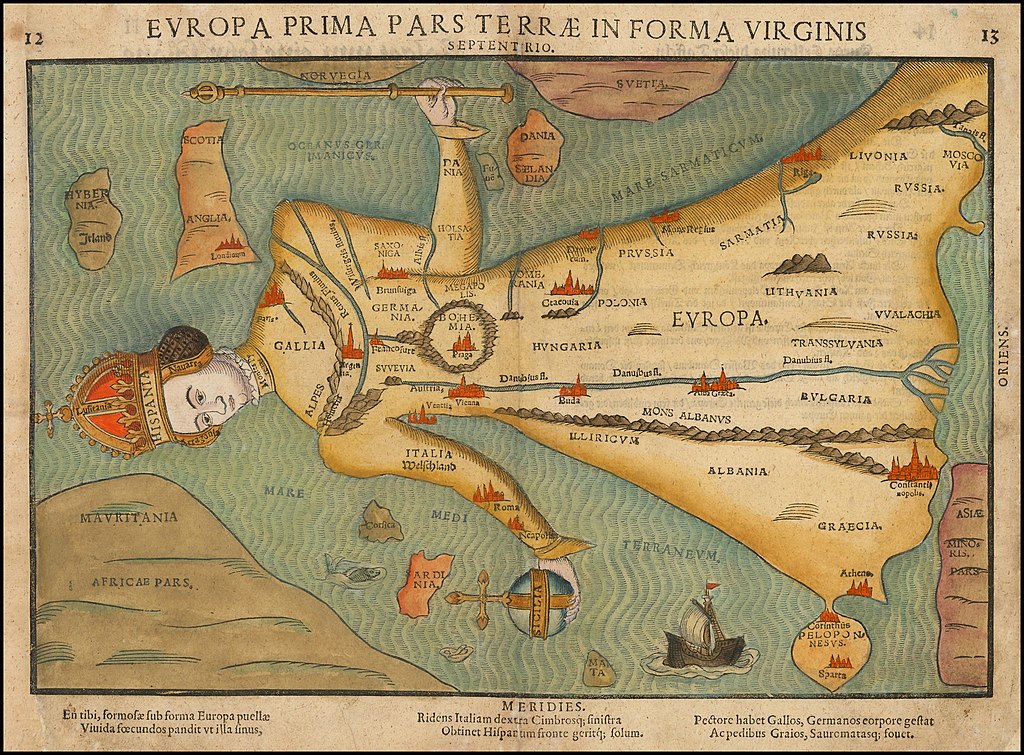

Europa Prima Pars Terrae In Forma Virginis, 1580s anthropomorphic map of Europe by Heinrich Bünting (1545–1606), 1580s, public domain.

Europa Prima Pars Terrae In Forma Virginis, 1580s anthropomorphic map of Europe by Heinrich Bünting (1545–1606), 1580s, public domain.