Juan Javier Negri has forwarded this article which La Nación, a large Buenos Aires daily newspaper, recently published as an editorial.

Athlete of Fano (Victorious Youth) 300–100 BCE, courtesy The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

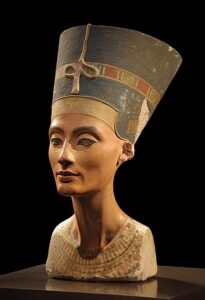

Two episodes linked to transcendent works of universal art have recently claimed worldwide attention. One of them is the bust of Nefertiti, from the fourteenth century BC, found in Amarna, Egypt, in 1912 and which has been on display in Berlin for a century. The other is the Athlete of Fano, a Greek bronze perhaps made by the sculptor Lysippus, personal artist of Alexander the Great, between the third and second centuries BC and found in 1964 in the sea off the small Italian town from which it now takes its name.

Both pieces share certain characteristics. Perhaps the most relevant is that of being remarkable examples of the artistic and creative capacity of those who conceived them. Another is their almost perfect state of preservation. A third, among other possible, is the degree of knowledge that they allow us to achieve about disappeared cultures.

Each of them is a paradigmatic example of the cultural cooperation – or lack thereof – between their countries of origin and where they are exhibited today.

The bust of Nefertiti was found by a German expedition, which had the necessary authorizations from the Egyptian government. Once the expedition’s task was completed, in 1913, a government official from that country established which pieces would remain there and which could be transported to Germany to be in the hands of James Simon, the German philanthropist who financed the expedition. Simon ended up donating his own property to the authorities of his country. Thanks to the wisdom of these behaviors, Nefertiti is celebrating these days the centenary of its peaceful exhibition at the Neues Museum in Berlin.

Bust of Nefertiti, painted stucco-coated limestone, Amarna, Egypt, photo by Philip Pikart, 8 November 2009, Neues Museum, Berlin, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

The Athlete’s story is almost the opposite of the previous one. The sculpture was taken from the bottom of the Adriatic Sea by Italian fishermen, who sold it on the black market to those who then illegally exported it from Italy. The J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu acquired it in 1977 for several million dollars. The Italian government resorted to all diplomatic and judicial resources to have the sculpture restored to it.

The latest episode was a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights following an appeal by the American museum against a 2018 Italian court’s forfeiture order, seeking an understanding that the restitution of the work to the Italian government would constitute a violation of the Getty’s property rights. The European Court held that not only was there no such violation, but that the museum had been negligent, at best, to have acquired a work of art of such importance without having exhausted a reasonable investigation about its provenance.

These facts show the imperative need for each country to have a sound and sensible cultural policy, which must take into account the need for a transparent market, with clear and precise borders, where collectors and dealers can freely negotiate the pieces obtained legitimately.

Fragmentary colored tiles used as wall-inlays, discovered by James Simon at Amarna, New Kingdom, 18th dynasty, 1351-1334 BC, © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung / Jürgen Liepe.

Monopolizing the possession of the works of art that make up the cultural heritage of a country in the hands of their respective authorities – as governments such as those of China, Turkey and Morocco intend – by amending the 1970 UNESCO Convention on Cultural Property can also be an effective tool to cancel the artistic expressions of certain cultural minorities.

Juan Javier Negri is an Argentine lawyer practicing in Buenos Aires. He holds a law degree from the University of Buenos Aires and a Master in Comparative Law degree from the University of Illinois College of Law. He is Chairman of the Board of Trustees of Fundación Sur, an organization preserving the history and creative works of 20th. century South American writers and artists. In 2015 he received the Uría Meruéndano Art Law Award granted by the Uría Foundation (Madrid) for his book ‘Banksy’s door: an essay on mistake and error in the purchase of artworks.’ In 2017 he was appointed to serve on the Board of Directors of the Fondo Nacional de las Artes, an autonomous state agency to provide financial assistance to artists and arts projects. Since January 2012, he is included in the Geneva-based WIPO List of Neutrals for Art and Cultural Heritage. He is also a member of the Court of Arbitration for the Arts, The Hague and the president of the Argentine Association of Comparative Law. He writes extensively on art law and cultural matters. He is currently teaching Art and Heritage Law at the Universidad de Palermo in Buenos Aires.

Athlete of Fano (Victorious Youth), detail Greece, 300–100 BCE Bronze with inlaid copper, courtesy The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles CA.

Athlete of Fano (Victorious Youth), detail Greece, 300–100 BCE Bronze with inlaid copper, courtesy The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles CA.