The Colgate University campus, 10 September 2008, Photo by Colgate University, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Administrators from Colgate University, a “little Ivy” liberal arts school in upstate New York, have worked for several years with officials the Mexican government to complete the return of almost 900 ancient artifacts to Mexico from the United States. Colgate University voluntarily repatriated 828 objects—adding to a previous return of 67 pieces—after conducting an internal provenance review. The artifacts, authenticated by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), included items from regions across Mesoamerica and ranged from 1500 B.C. to the early 16th century.

While the repatriation has been celebrated by Mexican officials as a triumph of cultural diplomacy, Colgate University framed its return as part of a broader institutional goal to “decolonize” its museum collections. University President Brian W. Casey and Longyear Museum Co-Director Rebecca Mendelsohn spearheaded this effort. Mendelsohn described the return as a pioneering act, stating, “If we are truly going to decolonize, really thinking about the significance of everything that we have in our collections to their communities of origin needs to be a part of the equation too.”

Ceramic fragments collected by David R. Hunter left for Colgate University in Mexican Ambassador’s Collection. Source Colgate University.

A formal letter of intent, signed by Dr. Casey and Mexican Consul General Jorge Islas López, initiated Colgate’s continuing process of review and potential restitution of still more objects from the university’s collections. Dr. Casey emphasized the university’s willingness to return any items deemed culturally or religiously significant to Mexico.

The voluntary repatriation effort occurred without evidence that the returned artifacts had been illegally exported or imported. The online catalog shows that the university’s collection had been gifted in 1993 by donors David R. and Barbara Hunter, but no other information about the Hunters was available on the university website. The Colgate announcement did not provide information on how the collection was made or the dates when the Hunters acquired them.

David R. Hunter, who died in 2000, was a lifelong leader as an administrator of philanthropies and “one of the first philanthropic officials to see foundations as an instrument for dealing with social and economic inequalities,” according to his obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle.[1] Among many other progressive projects, Hunter served as UNICEF’s Program Officer for Latin America from 1950-1959, living in Mexico for several years, where he was able to indulge his lifelong passion for archaeology, the likely background for his collection of Mesoamerican artifacts.

It should be noted that regardless of other restrictions that may have existed, Mexico did not have a national patrimony law explicitly vesting ownership in archaeological artifacts in the state until 1972.[2]

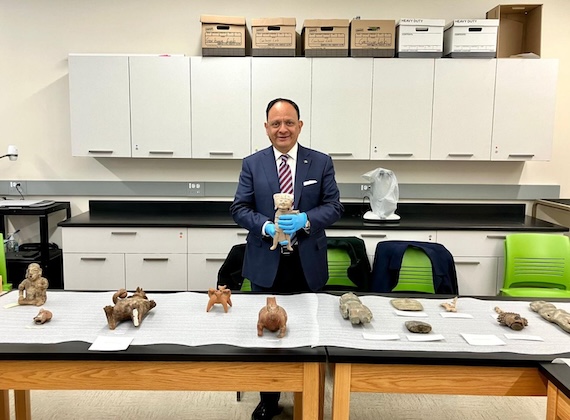

Jorge Islas López, Consul General of Mexico examining returned objects. Courtesy Consulate of Mexico, twitter.

Many of the items returned to Mexico had been held as part of an archaeological study collection meant to support student learning and cross-cultural scholarship. The artifacts chosen for return to Mexico were the ones most intact and artistically valuable for museum display. The 728 ceramic fragments left behind, simply labeled “unknown, Pre-Columbian,” appear to have been collected from the same sites at the same time. These potsherds were left behind as a “Mexican Ambassador Collection” for Colgate students.

Such a division seems questionable in light of the university’s pedagogic function. There is no indication that the returned items were of national importance to Mexico, or that they were in any way unique. Retaining the collection intact could have provided students with a broader understanding of Mesoamerican material culture. Failing to include the hundreds of potsherds in the return to Mexico meant that the returned materials had less archaeological value for scholars there, and left the potsherds behind without more particularized material to give them context.

Was this return necessary? Did Colgate University or Mexican officials consider sharing them – perhaps along the lines of the old concept of ‘partage’ – dividing the materials so that each benefited in both aesthetic and archaeological terms? There are tens of thousands of Mexican archaeological objects in university and public museum collections in the U.S. Did Colgate consider bringing Mexican students or scholars in to investigate the legal, political and ethical climate in which its collection was collected and exported from Mexico?

Ceramic fragments collected by David R. Hunter left for Colgate University in its Mexican Ambassador’s Collection. Source Colgate University.

It appears that Colgate’s decision to return the artifacts was not made due to alleged wrongdoing in their acquisition or importation, but as part of a broader political, symbolic effort to “decolonize” the university’s collections. ‘Decolonization’ generally relies on an assumption that objects’ acquisition was exploitative, that ownership by museums and foreign collections deprives countries of objects necessary to national identity, or that governments should control scholarship and ownership of the past. These premises often overlook both the facts of acquisition and the value of global access to the study of world cultures.

At their best, university collections of “other people’s art” honor the artists and their works, affirm the importance of cultural stewardship and scholarly exchange, and enable students and researchers outside of countries of origin to learn and engage meaningfully with global human history. Repatriation should be based on facts – and on the laws of the time – not today’s political rhetoric. Whatever the abstract ethical position one takes, it’s an error to ignore the facts of collection.

While the return has been lauded by Mexican officials as a moral and diplomatic victory, it should also raise important questions about the growing pressure on academic institutions to divest themselves of legally and ethically acquired study collections. In this case, there is not evidence that the artifacts were looted, smuggled, or stolen. Instead, they were studied, preserved, and served a clear pedagogical mission.

Colgate’s decision was made in good faith, but it represents a concerning precedent: one in which institutions may feel compelled to return items not due to legal necessity or the facts of acquisition, but under the weight of a politicized and increasingly absolutist narrative about identity politics and perceived historical injustice.

In the cafeteria of Colgate University. Photo by Stilfehler, 15 July 2017, CCA by SA 4.0 International license.

[1]. Obituary, David Hunter, San Francisco Chronicle, December 28, 2000. See also David R. Hunter, NDBB, David Hunter’s philanthropic career began as the creator of inner-city projects for the Ford Foundation that became prototypes for President Lyndon Johnson’s war of Poverty. Known as “the first venture socialist,” he helped fund a number of progressive projects throughout his life, ranging from women’s rights to labor union democracy to nonintervention in Central America to self-help in Appalachia, and serving at the Ottinger Foundation, Stern Fund, Akbar Fund, and Liberty Hill Foundation, among others.

[2] Federal Law on Archaeological, Artistic and Historic Monuments and Zones, April 28,1972, Official Gazette 6 May 1972, unofficial translation on UNESCO website.

Jorge Islas López, Consul General of Mexico examining returned objects. Courtesy Consulate of Mexico, twitter.

Jorge Islas López, Consul General of Mexico examining returned objects. Courtesy Consulate of Mexico, twitter.