For centuries, the societies of ancient Greece and Rome have been esteemed in the West as paragons of cultural excellence. Greek and Roman art, literature, politics, and philosophy have reigned supreme in the Western world’s collective historical consciousness. Latin remained the lingua franca of intellectual and religious discourse long after it was displaced as the vernacular, and the writings of Ovid and Virgil were necessary to an aristocratic education even in the 20th century.

The Renaissance – not just a re-birth, but a re-telling of Classical learning beginning in Italy in the fifteenth century – impacted European culture in ways that continue to be felt today. Among the intellectual legacies of the Renaissance are Neoclassical sculpture and architecture, and thousands of paintings and decorative artworks depicting scenes from Greek and Roman mythology. The Renaissance’s rediscoveries would also lead to eighteenth and nineteenth century colonialist campaigns in emulation of the Roman Empire, and more positive experiments with that great Athenian invention, democracy.

In the twenty-first century, we have our own ways of remembering, appropriating, and adapting the Classical legacy. Now that modernist and post-modernist architecture has driven out Neoclassical as the style of choice, the most visible public venue where we grapple with Greek and Roman culture is the movie house. While the last hundred years of film have revealed American filmmakers’ and their audiences’ disinterest in the classics per se, our fascination with classically-based themes endures in the bloody violence, fantastical monsters, and unbridled sexuality which we have come to associate with the cultures of the ancient Mediterranean.

Swords, Sandals, and Pepla

Agamemnon in pseudo-Turkoman ornamented armor. Troy (2004). http://moviecitynews.com/archived/specials/2004/troy_primer_04.html

Rome, whether as Republic or Empire, holds a clear preeminence over Greece as a setting for period piece movies. ‘Sword and sandal’ flicks – dramas, action movies, and even romances set in the age of the Roman Empire – are standard cinematic fare. The genre was pioneered by filmmakers in mid-twentieth century Italy, where such films are known as “pepla,” in reference to the ubiquitous costume tunics their actors don. Pepla, like their Hollywood counterparts, are more notable for their entertainment value than their historical accuracy. Aside from its sweeping historical liberties, Ben Hur (1959) famously includes a shot of a charioteer wearing a wrist watch. “Realistic” films set in the Roman period typically feature a bare-calved, gladius-wielding hero, doe-eyed ladies in clingy gowns, at least one gladiatorial combat, and an assassination or two, if not a complete coup d’état à la Julius Caesar. Our preconceptions also trump art historical visual accuracy; to my knowledge, no Hollywood film has shown classical sculpture or architecture as it once was: brilliantly painted and wildly patterned.

A Dearth of Temples

Perhaps unintentionally, the film genres inspired by Greek and Roman mythology also illustrate contemporary culture’s rejection of religion (even in our age of super-heroes, who turn out to be much more like us than gods). In most of the major works of Greek and Roman literature, from Homer to Aeschylus, Ovid and Virgil, the gods play major roles, where they are not themselves the protagonists of the narrative. Likewise, the most striking surviving examples of Greek and Roman artworks are depictions of deities and their worship. Examples include the National Archaeological Museum of Athens’ Artemision Bronze, the Louvre’s Venus de Milo and Nike of Samothrace, and the Vatican’s Apollo Belvedere, once hailed as the world’s most beautiful sculpture. Greece’s Parthenon and Rome’s Pantheon, two of the world’s most widely recognized and historically evocative buildings, both served as temples to the gods.

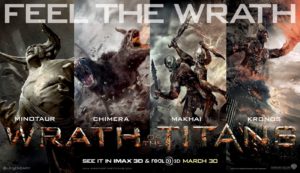

Wrath of the Titans (2013), banner poster.

In contrast, the human characters in movies based on classical myths often doubt their deities’ powers and even existence – a good example is the skeptical King Cassander in Immortals (2011). In Wrath of the Titans (2013), the waning faith of humanity in the Olympians is a key driver of the plot overall. Yet this skepticism – seemingly the most modern addition to the classical narratives – actually dates back to the golden age of Ancient Greece itself. Philosophers such as Protagoras and Aristotle expressed doubts about the Greek pantheon, while Socrates was charged with impiety for his religious skepticism.

Despite the important roles of gods attested by ancient art and literature, religion is almost an afterthought in films set in the Greco-Roman periods, and few filmmakers have translated ancient myths to the screen in any form recognizable to a student of the original legends.

In fact, modern cinema’s version of Greco-Roman mythology is a mess. Filmmakers usually take the jewelry-store robbery, smash and grab approach to Classical sources. The average ‘Olympian’ film features a jumbled handful of names, narratives, and locations, as if they were seized at random from the cases of a museum. These fractured elements of Greco-Roman tradition are then assembled into a haphazard plot, and the gaps between mismatched components filled in with plenty of shipwrecks, lovemaking, and armed combat between heroes, monsters, and even the gods themselves.

Muscle Men

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson as Hercules. http://screencapped.org/movi//displayimage.php?album=18&pid=55345#top_display_media

The mythic movie genre is well represented by Hercules (2014), starring the famously muscular Dwayne Johnson as its eponymous hero.

This Hercules, we are given to understand, is a man renowned for his strength, rumored to be the son of Zeus and despised by Hera. So far, so classic. The film is in fact exceptional for mentioning the two most notable, yet most often omitted, aspects of the Hercules myth: his accidental murder of his wife and children in a fit of rage, and the Twelve Labors which he performed in penitence for his crime. Confusingly, the movie shuffles the order of events in his life, so that the murder of his family happens after he completes his labors, which are in this version not his own achievement but shared with a troupe of fellow heroes.

The rest of the film is a wholly original (that is to say, non-classical) story of invasions, betrayals, and secret plots, liberally speckled with familiar names given to characters in unfamiliar roles. This film’s “Hercules” is captain of a band of roving mercenaries, including an Amazon woman, “Atalanta of Scythia.” (How an Amazon woman acquired the name of a Boetian/Arcadian princess, only the screenwriter knows.) Hercules’ other companions did exist in classical sources; both Iolaus, his nephew, and Autolycus, who according to some myths taught Hercules to wrestle, appear in roles very near to the original texts.

In fact, not one, but two films inspired by the Hercules legend appeared in 2014. Hercules did reasonably well at the box office, but the second movie, The Legend of Hercules, was a flop. This might gratify mythology purists. If Hercules took liberties with the original myth, Legend simply ignored ninety-five percent of it. It is a classic tale in name only: suffice to say that Hera incites Zeus’ infidelity to bring about Hercules’ birth, Hebe is downgraded from a goddess to a princess of Crete, and Hercules is shown in gladiatorial combat brandishing a Roman gladius.

Pulping History

Hercules and his action figure, in Disney’s animated Hercules, 1997.

Altogether, The Legend of Hercules reflects a general condition afflicting modern mythological films: the tendency to blend Greek and Roman legends, pantheons, and cultures into one monolithic Greco-Roman whole.

(Mea culpa. My own use of the amalgamating terms ‘Greco-Roman’ and ‘Classical’ reflects the common error: failure to distinguish between these very distinct cultures and periods. Though the Greek city-states and the Roman Empire existed simultaneously for part of their history, the cultural high-point of Ancient Greece was centuries before the apogee of Roman culture; and although the Romans emulated Greek art and architecture, studied Greek philosophers, and adapted Greek gods, myths, and legendary heroes, there are as many differences between their two cultures as there are similarities.)

There is a big difference between the Roman war god Mars and the Greek Ares but you wouldn’t guess that from how they are portrayed in the movies. In film, Greek or Roman gods are generally called by their Greek names. Perhaps this is because, to the modern ear, their Latin names (Jupiter, Mars, Venus, etc.) are more likely to recall planets than deities.

On the other hand, the gods’ dress, arms and armor, are far more often Roman than Greek, regardless of when or where the film takes place. Classicism in movies is marked by this amalgamation of cultures, and the erasure of historic variations in religion, dress, and language between Rome and its provinces, or between the city-states of Greece, Italy, and Asia Minor.

Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Lightning Thief (2010), http://www.syfy.com/syfywire/the_real_myths_behind_per

It’s too bad. Hollywood is missing out. The surviving library of narratives from the Ancient Greek period alone is vast, diverse, and full of the kind of romance, scandal, and shocking violence modern movies thrive on. The Illiad is as packed with gory combat sequences as the bloodiest modern action film, while The Odyssey features sea monsters, the slaying of 108 suitors, and the seductions of the doggedly infatuated Calypso. All this should, by right, tempt modern filmmakers. When Roman elaborations, variations, and continuations of the Greek myths are counted up, the number of potential big screen narratives swells into the thousands.

Yet cinema-goers have been treated instead to repetitions of a small selection of stories. Hercules is by far the most popular character to be resurrected for film: recent American productions include the two 2014 movies and Disney’s animated Hercules (1997). Theseus (or versions thereof) appears in Minotaur (2006), Immortals (2011), and Atlantis (2013). Perseus is the protagonist of Clash of the Titans (1981), the 2010 remake of same, and its sequel, Wrath of the Titans (2013), while his namesake, Perseus Jackson, is the hero of Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Lightning Thief (2010), and its 2013 follow-up, Sea of Monsters.

On the other hand, there is not a ‘classical’ rendition of the tale of Orpheus. The story has been given a modern remake in allusive form; for example, French director Marcel Camus’ Black Orpheus (1959), is set during Carnival in Brazil. Jean Cocteau’s delirious Orphée (1950) was also set in the modern world, rather than ancient Greece.

Sex and the Eternal City?

Ava Gardner and Dick Haymes, One Touch of Venus, http://screencapped.org/movie/h/displayimage.php?album=18&pid=55345#top_display_media

So few Greek and Roman gods and goddesses are depicted in films, that viewers could be forgiven for thinking that the Classical pantheon was limited to a half-dozen grouchy, bearded men. Zeus, Poseidon, Hades and Ares make up the vast majority of divine manifestations in film. The ever-present and relentlessly meddlesome Olympians of the Classical canon are generally relegated to offstage dramatics in the movies, or given marginal roles.

In the 2004 film Troy, which narrates a dramatically compressed version of the Trojan War, the gods are frequently mentioned, but only Thetis, mother of Achilles, appears on screen. The Greek deities’ role as active participants in the strife is entirely removed.

Movie goddess roles are even more marginal. Athena sometimes plays a sidekick part in Zeus’ battles, Hera is trotted out occasionally to play the jealous wife, or more often bowdlerized into an enabler and legitimizer of Zeus’ dalliances with female mortals. Aphrodite (despite cameo appearances in several films) has not had a major speaking role on the silver screen since 1948, when Ava Gardner portrayed her as a goddess out of her proper place and time in One Touch of Venus.

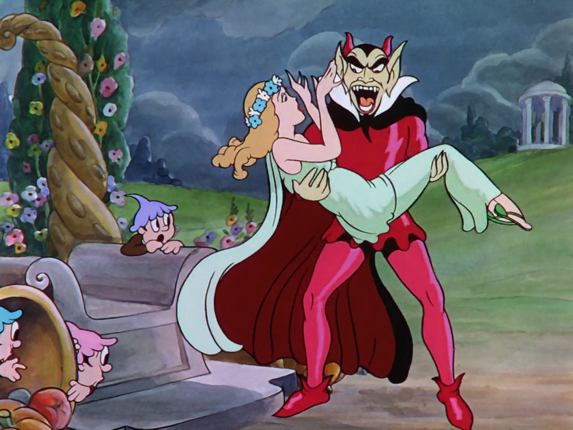

Persephone has had her story told only once by a movie house: in Disney’s Silly Symphony animated short, The Goddess of Spring (1934). There, a Mephistophelian cartoon version of Hades kidnaps Persephone from an Arcadian landscape inhabited by dancing gnomes in flower-shaped hats and pointy-toed shoes.

The Goddess of Spring (1934), http://disney.wikia.com/wiki/File:Persephone_(The_Goddess_of_Spring)_05.png

Admittedly, Persephone’s story is a difficult one to render innocently enough for a PG-13 rating. Abducting and forcibly “marrying” young women is frowned upon these days, and most audiences would find the myth’s ending, in which the victim is compelled to co-habitate with her kidnapper for six months of every year, something of a downer.

Greek myths are rife with sexual activity, most of it extra-marital and much at best dubiously consensual. Filmmakers tend to scrub this uncomfortable aspect of life on Olympus out of their movies. Disney’s 1997 animated Hercules turns its hero into the legitimate son of Hera and Zeus – going so far as to show a divine baby-shower for the infant god. When Zeus is admitted to be the father of half-mortal offspring, his infidelity is either tidied up by being condoned by Hera, or the fact that he is already married is concealed by omitting Hera (along with all her fellow goddesses) from the narrative entirely. (Disney had hoped to premiere Hercules at Pnyx Hill, a historic site in Athens, but its request was declined after members of the Greek government watched, and presumably disliked, the film. One newspaper at the time called Hercules “another case of foreigners distorting our history and culture just to suit their commercial interests.”

The ‘Classical’ Liberties of Film-making

Hercules and Pegasus make their mark, in Disney’s Hercules (1997).

There are classical precedents for the confused blending of history with myth which allows one character in Disney’s Hercules to cite Odysseus as a hero predating Hercules himself, or that enables Xena, protagonist of the hit TV show Xena: Warrior Princess to encounter Ares, Odysseus, and Virgil within the same six-year period.

Several of the best-known Greek myths served as origin stories for real Greek cities and states, which identified mythic figures as their hero-founders. Julius Caesar famously claimed to be a direct descendant of Aeneas, the legendary founder of Rome and son of the goddess Venus. Roman emperors routinely achieved apotheosis at their deaths, blurring the line between human and divine, reality and religion.

Even the copy-and-paste architecture and dismaying disregard for cultural and periodic distinctions in the sets and costumes of modern films has its historic origins. After all, when Rome subjugated the Greek states, wealthy Roman citizens imported thousands of Greek statues to ornament cities and villas, and today we know many Greek originals only through Roman copies. Fashions in both Roman and Greek art and architecture came and went, including phases of deliberate archaism.

It is tempting to imagine the existence of an authentic and pure Roman or Greek milieu, or of a single foundational set of myths from which our modern movies could draw inspiration. The truth is, however, that the stories which have come down to us are, like the archaeological record, a palimpsest. Pre-Hellenic, poly-ethnic religions and local deities were absorbed by the faiths of more dominant cultures; authors added their own interpretations to even more ancient tales or disputed their sources’ veracity. The origins, achievements, and legacies of Greek and Roman heroes evolved through time, as their stories were passed on, appropriated for political purposes, or adjusted to suit the requirements of new religions.

Syncretism: religious, cultural, artistic, and literary, has long been characteristic of life in the Mediterranean. This does not wholly excuse the hash modern directors have made of the ancient myths and legends, but it does make it easier to relax and enjoy a little Greek gladiatorial combat, or to blink at the sight of camels in Troy and Central Asian jewelry on both Agamemnon’s cuirass and Priam’s best court dress (see Troy, 2004).

The centuries of scholarship that kept the classics alive to this day also contributed their share of original additions to the canon; Virgil was a bold borrower of Homer’s poetry as the foundation for his own writings, while dramatic but not exactly well-researched paintings of scenes from Ovid ornamented the palaces of many a Renaissance prince.

Yet We Love the Classics

Andromeda and Jane Bennet

http://clash-of-the-titans.wikia.com/wiki/Andromeda?file=Andromeda_still.jpg

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/302726406172862537/

The multifaceted, historically contingent, and often-altered condition of the classical tradition in Western culture is exemplified by the curious case of British actress Rosamund Pike.

In the 2013 action-drama Wrath of the Titans, Pike plays a surprisingly combat-ready version of Andromeda, alongside co-star Sam Worthington, as Perseus. Despite her sturdy leather cuirass and knack for taking out monsters, Pike will be readily recognizable to Jane Austen fans as Jane Bennet, who the actress played in Pride and Prejudice (2005). As the Greek princess Andromeda, Pike sports exactly the same classical-statuary-inspired hairstyle which she wore in Pride and Prejudice. Ms. Bennet’s fashion sense is typical of the Neoclassical period in which she lived, when Greek and Roman art, architecture, and dress were all the rage. Two eras, two characters, one chignon.

In a way, this visual parallel encapsulates our entire history of cultural engagement with the Greco-Roman mythological legacy – from the original stories of Perseus and Andromeda, through the Renaissance’s excavations of Roman and Greek artifacts, which facilitated the development of neoclassical fashion based on Classical statuary, into our own era, when we borrow here and there from history, art, and tradition, and mingle it with our own tastes, for nudity, violence, and computer-generated monsters.

The Kraken arrives for Andromeda, in Clash of the Titans (1981)

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0082186/mediaviewer/rm3633125632.

The Kraken arrives for Andromeda, in Clash of the Titans (1981)

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0082186/mediaviewer/rm3633125632.