Let’s have a public access database of Egyptian and Nubian antiquities in circulation so that we have a clear record of what is held by collectors and the trade. Managed by the British Museum, it will allow us to check provenance and raise red flags over questionable items – better due diligence all round. It will also help spread confidence among the trade and collectors over items that have been subjected to this vetting process and published unchallenged on the database for a lengthy period. In short, the database will not only document material that is on the art market legitimately, but also feature objects reported stolen and missing, encouraging anyone who spots them to help enable repatriation. The data will be housed in an open-source semantic database, available on-line (with more sensitive data shielded).

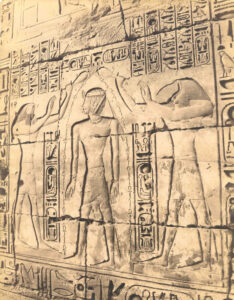

Photo by Zangaki, No. 1012, wall relief from Luxor, private collection.

As a concept, the CircArt database* was a slam dunk. Its proposed structure and function addressed concerns about illicit trade expressed by source countries such as Egypt, ethical and practical issues arising among museums and the on-going fears of dealers, auction houses and collectors caught in the crosshairs of anti-trade campaigning.

A call for funding document (vetted by the British Museum’s Department of Egypt and the Sudan, which oversaw the negotiations) supporting the proposal for a 4-year pilot project stated in February 2017: “Due to its public nature, the database will be a major disincentive to thieves and unscrupulous middlemen – far more effective, for instance, than current, non-public databases, which are maintained by teams with no expertise in the subject and limited resources. The project, if funded, will be a powerful tool to help protect the legitimate antiquities market from being infected by illicit material.”

So what went wrong?

Having been closely involved in negotiating terms between the trade associations and the Egypt and Sudan department at the BM in developing the database and securing funding for it, it seems to me that what started as a constructive, ground-breaking and potentially far-reaching initiative effectively died at birth through a mixture of naivety, tunnel vision and breach of trust.

The Egypt and Sudan department soon discovered securing project funding from the British Council (around £1.7 million was granted in all over the course of the project, I understand) depended on trade support. That meant negotiating with the Antiquities Dealers’ Association (ADA) in the UK and the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA). This is where I came in.

As an adviser to both associations, and someone whose knowledge of the trade extended back twenty years, chiefly in my role as Editor of Antiques Trade Gazette, I was well aware of the declining levels of trust between the trade and museums as curators came under increasing pressure to sever ties with dealers and auction house specialists on (in my view misguided) ethical grounds.

This was a fantastic opportunity to reverse the rot and build something positive for the future. However, with trust as eroded as it had become, establishing a constructive working relationship meant being crystal clear about the terms of engagement so that there could be no misunderstanding.

Photo by Zangaki, No. 996, wall relief from temple at Karnak, private collection.

The ADA and IADAA immediately saw the potential of the database, as set out above, but they were equally wary of signing up to it without guarantees about its remit and how the trade’s contribution to the project would be acknowledged.

A long drawn out series of meetings and emails between the ADA and the Egypt and Sudan department eventually led to a consensus, which in turn brought forth the vital letter of support from IADAA to secure the funding.

So what were the trade’s terms?

Firstly, the ADA and IADAA wanted absolute assurances that the database would be public in the manner described above and would not be used simply as a tool for source countries and anti-trade campaigners to make groundless and vexatious claims against legitimate objects. “So it is essential the Egyptians agree to co-operate fully with this project and to take a different approach or this whole project could back-fire,” the ADA warned in an email setting out the terms to the Egypt and Sudan department in January 2017.

Secondly, the trade proposed a statute of limitations on ‘orphan’ objects whose documented provenance was lacking to the extent that their source and history of sale and export from their home country could not be confirmed. Once published on the database, they should be deemed legitimate if they went unchallenged after a set period to be agreed by the source countries whose items appeared on the database. This condition could have been a breakthrough for the most intractable debate in the sphere of antiquities but was never accepted.

Thirdly, the project should make clear distinctions between the legitimate trade and illicit activity.

Fourthly, the trade would undertake to publish all records relating to an object alongside its image on the database provided they were not subject to any restrictions, such as data protection and privacy laws, which might prevent them from posting comprehensive data.

Fifthly, where a challenge was made, clear protocols should be established so both parties could work within a set of pre-agreed rules of engagement so as not to unduly damage the reputation of the owner/custodian of the object.

Finally, while acknowledging that the database needed to remain entirely independent and managed by the Egypt and Sudan department, the associations set out detailed terms on how the trade’s contribution to the project and its funding would be acknowledged. These terms included an agreed standard boiler plate summary added to every press release.

Photo by Zangaki, No. 914, Thebes colosses, private collection.

In a February 2017 email, the Egypt and Sudan department representative curator, Marcel Marée, who would be in charge of CircArt, told the ADA that the trade’s role would be properly acknowledged.

(Later, in response to questions from Antiques Trade Gazette in April 2020, Marée excused the failure to honour the arrangement by saying that the BM had not signed any formal agreement – a particularly discreditable statement, in my view, bearing in mind his earlier promise and the number of times he and his colleagues had viewed and edited the terms of the agreement to win support from the ADA and IADAA.)

While the Egypt and Sudan department used ongoing discussions and further amendments to the documentation to try to row back from some of the undertakings, this was essentially the basis on which members of the trade associations were consulted, and these were the terms under which they agreed to lend their support to secure funding. They remained in place after further review by senior staff at the department, constituting what Neal Spencer, Keeper of Ancient Egypt and Sudan, suggested should be referred to as a draft Memorandum of Understanding by early May 2017 – clearly a statement of intent for all parties involved. The deadline for applying for the funding was June 23, 2017.

Satisfied with the way negotiations had progressed with the ADA and the assurances given by the Egypt and Sudan department, on June 13, ten days before the funding application deadline, IADAA wrote to Spencer and Marée, setting out the terms of its support for the database. After a few tweaks from Marée, the final wording agreed to was as follows:

Having been consulted over the British Museum’s proposal to establish a database relating to circulating Egyptian and Nubian artefacts, IADAA understands that its purposes are:

- to create greater transparency in record-keeping of items in circulation among collectors, dealers and auction houses;

- facilitating research and the identification of objects, availing of the Egyptological expertise of the British Museum and its partners;

And thereby:

- reducing crime;

- enhancing due diligence; and

- promoting constructive relations between collectors, dealers/auctioneers, museums, law enforcement and antiquities officials.

To these ends IADAA is happy to endorse this project and encourage its membership to co-operate with the establishment and development of the database wherever possible, particularly in the provision of data and images.

On top of what had been negotiated with the ADA, this set the stage for an exciting and co-operative project.

Photo by Zangaki, No. 919, Children at site of temple at Thebes, private collection.

Official news that the funding had been awarded came through on January 3, 2018, although it was already clear from discussions the month before that something had gone seriously wrong. While the Ministry of Antiquities, Egypt had been listed as a project partner in the British Council’s announcement, alongside The National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM) and The Art & Antiques Unit of the Metropolitan Police Service (New Scotland Yard), there was no mention of the trade at all. (The auction houses had initially been listed but that mention had been withdrawn within a matter of hours).

The ADA was told that the Egyptians had objected so strongly to trade involvement with the project that the Egypt and Sudan department had agreed with the British Council that any mention of the trade’s involvement should be expunged.

It then emerged that the Egyptian Antiquities Ministry feared losing public support for the project if the Egyptian media discovered that the trade was involved. Worse, it transpired that formal acceptance of the project by the Egyptians had not been secured prior to the launch announcement, leaving them free to pull out if their demands were not met. With the added risk of being barred access to excavations and records within Egypt as a result of upsetting the authorities over the matter, the Egypt and Sudan department was in a hole.

Despite assurances that the department would rectify this abject failure to honour its commitment to the ADA by issuing its own press media announcement later in the month (never honoured satisfactorily), the damage was done. The Egypt and Sudan department had secured funding on the prerequisite basis of trade involvement and support – a condition set down by the British Council itself – and the associations’ hard-won trust of their members had been betrayed at the first test.

Needless to say, all the assurances the associations had been given, from crediting the trade properly in the BM media release to how the Egypt and Sudan department would approach the project, as well as proper credit on the website as a project partner, were abandoned. Emails to the BM were met with unsatisfactory answers. Eventually, a follow-up meeting took place between the ADA, Spencer and Marée in March 2018. This led to the ADA outlining its concerns via email on April 26 in which the association attached amendments to the text for the Egypt and Sudan department announcement, which Marée and ADA chairman Joanna van der Lande agreed after further discussions.

While the ADA appeared to be getting somewhere, requests for further contact and discussions from IADAA chairman Vincent Geerling – whose endorsement had secured the funding – continued to go unanswered.

Photo by Zangaki, Karnak, No. 996, private collection.

Despite ongoing assurances from Marée, when Martin Bailey’s Art Newspaper article Scotland Yard joins global crackdown on looted pharaonic antiquities was published on April 30, 2018, following a briefing from Spencer and Marée, it became clear that those assurances counted for nothing. My own letter to the Art Newspaper (see below), picking up on this, attempted to set the record straight.

Even then, the ADA and IADAA tried to continue a dialogue with the Egypt and Sudan department, with the odd call and email, and another meeting with Marée on December 3, 2018, at which Geerling was also present, but then another article, this time in Artnet News on January 21, 2019, made it clear that they were wasting their time.

In it, while yet again saying nothing of the trade’s essential contribution to securing the funding for CircArt and supporting the initiative in spirit as well as in practice, Marée was quoted as saying: “We have become alarmed at widespread practices in the art market. The more you pay attention, the more you notice patterns of laxity, misconduct or obfuscation.”

Having initially been assured that the database would not be used as part of a witch hunt against the trade, the ADA and IADAA were less than pleased when the article also included the following: “But to encourage transparency, the site will list every auction house and dealer that submits artifacts for documentation and study. “Those who do not will be conspicuous by their absence,” Marée said.

It appeared that the betrayal was complete.

Again, I attempted to set the record straight and the author of the Artnet News article agreed that a follow-up piece seemed required, but it never happened and the article was then used by UNESCO and others to disseminate a false picture of the database and its relationship with the trade.

Soon afterwards the Egypt and Sudan department confirmed to the ADA what it had been warning about for months: that the Egyptian Ministry for Tourism and Antiquities had decided not to endorse the project after all and had said that it would only consider endorsing it if the database was closed rather than open-source.

Attempts to rectify the situation dragged on for months. The ADA met with Marée again on February 25, 2019 – a three-hour meeting whose draft minutes were later sent to Marée for his approval. However, after two further emails chasing his response, he went silent, never to respond again.

It became clear when the CircArt platform finally launched in early 2020 that it was to bear little resemblance to what had been proposed as a positive joint initiative with the trade.

It will come as no surprise that having been let down so badly after showing such a high degree of trust and good faith, the trade associations and their members wanted nothing more to do with the project, especially as the database would not be open as promised.

The BM may not have signed a contract, but it seems clear to me that a formal agreement with the Egypt and Sudan department existed because, as all parties were well aware, both the ADA and IADAA’s support was conditional on the much-edited terms that they thrashed out with the department, which referred to the final terms as a draft Memorandum of Understanding. In using that support to secure the funding, the department must have known that it was effectively agreeing to honour those terms. However, it did not do so.

Despite all of this, the two trade associations continued to look for answers that would rescue their support for the project, as Antiques Trade Gazette detailed in an article on April 20, 2020.

Photo by Zangaki, wall relief, private collection.

It is an irony that having hoped to create a comprehensive database of Egyptian and Nubian objects, I understand that neither the Egypt and Sudan department at the British Museum nor the Egyptian Ministry for Tourism and Antiquities subjected their own collections to its scrutiny.

The Egypt and Sudan department originally set out this vision for the database in its call for funding document in January 2017: “After the 4-year kick-start, regular updates to the database will become an integral part of our department’s daily tasks, with continued collaboration from colleagues in Cairo and Khartoum. We will continue to take trainees from Egypt and Sudan as an extra component in our annual International Curatorial Training Programme, ensuring continued success in mutual collaboration.”

The reality is somewhat different. The project came to an end in February 2021 and one wonders what was achieved after such a failure to keep those it needed for support on board?

It is interesting to note the findings it published on its website. It reads: “While developing the system, CircArt recorded and researched more than 50,000 objects advertised on the open market and on social media. The project identified more than 1200 images and videos of potentially trafficked objects.”

That means that at least 97.6% of everything the project assessed raised no suspicions. How much of the remaining 2.4% was later confirmed as fake or looted? In other words, what evidence was finally provided of criminal activity by CircArt? We continue to await clarification on this.

For years now, governments, NGOs, law enforcement and academics have demanded trade co-operation in tackling crime associated with cultural property. At the same time, despite frequent offers from the trade associations to take part, these same groups have largely excluded the trade from the debate about what might work in beating the criminals. The reaction of the Egyptian Ministry for Tourism and Antiquities to the trade’s involvement in what had the potential to become the leading project of its type in tackling crime sends exactly the wrong message to dealers, auction houses and collectors. It seems that the only conditions under which the ministry might even begin to consider trade involvement is the trade’s annihilation. Who would agree to such terms?

The CircArt project should have heralded a new age of constructive co-operation, building trust on all sides and finally putting forward a solution for the seemingly intractable problem of ‘orphan’ objects. Instead, it appears to have been little more than an exercise in institutional aggrandisement and folly with, yet again, the taxpayer footing the bill.

* CircArt is the Circulating Artefacts database with Marcel Maree, curator in the Department of Egypt and the Sudan at the British Museum, its founder and project director.

Text of Letter from Ivan Macquisten to the Art Newspaper, No. 302, June 2018:

Trade bodies were essential in establishing anti-looting initiative

Your article Scotland Yard joins global crackdown on looted pharaonic antiquities (30 th April), (The Art Newspaper, May p8) makes me outraged on behalf of the trade associations whose leading role in this initiative appears to have been airbrushed from the record. To set that record straight, the Antiquities Dealers’ Association and the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art – both of which I advise – were instrumental in securing funding for the project and getting it off the ground.

Both associations have been working hard with the British Museum to ensure not only that such a database is effective, but that by acting as role models in their support for the project, they would encourage the rest of the trade to become active supporters too.

The success of such a scheme could be the first step in creating a database with a far wider remit, which would make due diligence a much more effective tool, while providing the authorities with a far stronger armoury for taking on the criminals.

My fear, in advising the associations on their involvement in this project, was that, yet again, their efforts would be glossed over and they would be left out in the cold. My suspicions appear to have been well founded, as the art market has been implicitly portrayed as a passive but unruly child whose activities the project is designed to rein in, while all the credit has gone to Scotland Yard, the British Museum and the governments of Sudan and Egypt, the last two of whom played no active role in devising the project, to my knowledge.

For years, non-governmental organisations, academics, archaeologists and lawmakers have berated the trade – often unjustly and on the basis of inaccurate and unchecked information– demanding that it get its house in order, co-operates with the authorities and helps to track down the looters and smugglers whose crimes do so much to damage cultural heritage. These associations have led the way in such co-operation, with very little thanks for doing so.

I am further interested to note that British Museum Keeper Neal Spencer has seen “a serious increase in the illicit trade in pharaonic antiquities in recent years.” Statements like this should be properly qualified. Let’s have the evidence to show this and put it on record.

The trade has every incentive to help raise standards and beat crime, quite apart from its own interest in protecting cultural heritage. As the recent arrests in Barcelona have shown (in April police in the Spanish city arrested two men suspected of selling antiquities looted from sites in north Libya by groups linked to Islamic State), when criminals strike they do untold damage to the reputation of those in the trade who act honestly.

My advice is as follows: not until those wishing to engage the art market understand that ‘engagement’ means listening and reciprocating, not simply handing down orders for dealers, auction houses and collectors to follow, will we make any real progress on this front.

Ivan Macquisten

Surrey

• The British Council, which is funding the project with £1m of government money, records the three partners as Scotland Yard and the antiquities departments of Egypt and Sudan. In a full interview, Neal Spencer gave his evidence for believing that there has been “a serious increase” in illicit trade; for reasons of space, we reported his conclusion.

Julia Michalska, deputy editor of The Art Newspaper

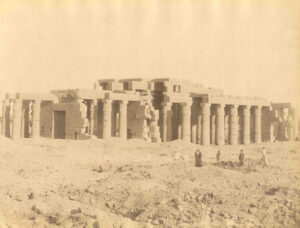

Photo by Zangaki, Luxor No. 919, Le troi Ramses de Louqsor, private collection.

Photo by Zangaki, Luxor No. 919, Le troi Ramses de Louqsor, private collection.