“They never really care about culture. This is the nature of the communists. To destroy the old world to rebuild the new one. They are not clear about what is most important in the so-called traditional art classics. The zodiac is the perfect example to show their ignorance on this matter.”

Ai Weiwei in a video on his Circle of Animals / Zodiac Heads.

China is rewriting its history to fit the ideas and agenda of its current political leadership. Part of that exercise includes encouraging Chinese buyers to bring ‘stolen’ art back to China. Chinese newspapers and magazines feature claims that there are millions of “looted” objects in foreign museums taken during military incursions against China in the 18th and 19th centuries. “Looted,” in these semi-official contexts, means not only items taken after battles, or even sold during lengthy periods of political weakness in the 19th and early 20th century. It can also refer to the millions of Chinese goods, such as ceramics and textiles, that circulated for centuries around the world as part of ordinary international commerce.

Some say that China’s government may be looking the other way when Chinese collectors acquire art stolen from foreign museums. A recent article by Alex W. Palmer in GQ, The Great Chinese Art Heist, raised the question, is the Chinese government behind one of the boldest art-crime waves in history?

Almost all art being imported into China is purchased legitimately, of course. Just as 19th century Western consumers acquired Chinese decorative arts for their pleasure and ancient examples of China’s culture for their growing museums, contemporary Chinese buyers are doing the same, building major collections that supplement and enhance the vast collections of Chinese art in its government museums. With China’s emergence as a world economic power, Chinese buyers have become the primary consumers of Chinese art in the global market. At the same time, the domestic Chinese art market has grown from zero in the early 2000s to currently around $1 billion per year, outpacing all other international markets. The majority of the artworks imported into China are sourced in Europe and the United States, both of which have experienced massive outflows of Chinese art over the last decade. (See: CPN’s market analysis in: Will US Embargo on Art of China & Tibet be Renewed?, Cultural Property News, April 10, 2018.)

Poster for the Chinese Dream.

There are multiple factors driving the return of art from the West to China. A billionaire class of Chinese collectors is eager to establish private museums, and the close ties between major Chinese auction houses and members of the government encourage monopolistic behaviors. Beijing Poly International Auction Co., Ltd., the cultural arm of the arms manufacturer Poly Group is controlled by the family of former leader Deng Xiaoping. The second largest auction house, China Guardian, is run by Chen Dongsheng, the grandson-in- law of Mao Zedong. There is an underlying policy of glorifying China’s heroic past, the “Chinese Dream” of President Xi Jinping and its promotion of Han cultural values.

Diplomatic efforts under the guise of protecting Chinese archaeological sites have helped China to increase its market share. In 2009, the U.S. State Department shepherded China’s request to prohibit imports of Chinese art through a malleable advisory committee process. China had sought import restrictions on virtually all art, textiles, antiques and antiquities from the Prehistoric period to 1912. The resulting agreement, which has been renewed and is still effective, was not as broad as requested by the Chinese government, but it covers all art through the Tang period and a limited range of items up to 1760.

Stealing it back?

Cultural Property News has followed apparent thefts-to-order of Chinese art since 2015 in a series of articles that examined both monetarily and politically driven thefts from European museums. Between 2010 and 2015 there were major thefts of Chinese art from museums across Europe; from the Chinese Pavilion on the grounds of Drottningholm Palace in Stockholm, the China Collection at the KODE Museum in Bergen, Norway, Durham University’s Malcolm MacDonald Gallery at the Oriental Museum, the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge University, at the China Collection at the KODE Museum in Bergen, Norway and from the grand Chinese Museum at the Château de Fontainebleau.

Police recovered this large jade bowl with a Chinese poem written inside that dates back to 1769 that was stolen from the Oriental Museum at Durham University.

The justification for bringing Chinese antiques “home,” even by stealing them, stems from a sense of loss and humiliation instilled by the Chinese government. Since the 1990s, the curriculum in Chinese public schools has focused on the idea that the plundering of Imperial wealth between 1839 and 1949 was a deliberate attempt to crush the spirit of the Chinese people. During this period, dubbed the ‘Century of Humiliation,” the Western powers’ removal of art and antiques was part of Western political domination. Specifically, the 1860 sacking of the Old Summer Palace and the looting of its cultural treasures continues to be seen as a crushing reminder of China’s political weakness. The Yuanming Yuan, or Summer Palace, was never rebuilt, and its ruins were left as a reminder of what imperialist British and French forces did to China.

The international museum community is shocked by China’s apparent lack of concern about the thefts and allegations that the government and key corporate players may actually be behind them. Perhaps they shouldn’t be. What museums regard as unconscionable thefts, many in China see as a justifiable taking of Chinese property back from thieves.

While Chinese officials have never openly supported the thefts, Palmer quotes Jiang Yingchun, the CEO of Poly Culture, an offshoot of the Poly Group conglomerate: “We can’t ignore that the art was taken illegally,” even if it was being well cared for, he said. “If you kidnapped my children and then treated them well, the crime is still not forgiven.”

Art in foreign museums deemed stolen

The super-wealthy in China who have helped to make it the largest art market in the world have achieved great prestige as collectors; some are museum builders or supporters of scholarship, like major art collectors in the West. But in China, art collecting represents more than this: collecting ancient and antique art is a recognized expression of patriotism. Thus, some major acquisitions are more about returning objects that have political symbolism, than an act of connoisseurship.

In a 2010 article in China Daily, high-ranking officials from China’s major auction houses referred indiscriminately to items shipped overseas in the global Chinese export trade from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) on as “looted.” Zhao Xu, director of Poly International Auction Co Ltd. told China Daily that, “”Buying looted artwork has become high-street fashion among China’s elite, especially in the past year.” The same article stated blandly that, “as many as 1.64 million looted Chinese relics are in the hands of 47 overseas museums, with another 16.4 million owned by individuals, according to a Xinhua News Agency report in 2009 that cited statistics from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.”

The British Museum responded to accusations that its collections were largely looted stating that,”There is clearly a serious misunderstanding,…There are around 23,000 objects in the museum’s Chinese collection as a whole, the overwhelming majority of them peacefully traded or collected, many indeed made for export. Very few objects entered the collection in the context of, even less as a result of, [the Opium Wars].”

In 2016, CPN detailed how UK and European museums had been targeted for years by local criminal gangs that were hired by agents for Chinese buyers. The most sought after objects in the heists were those taken by French and British forces from the Summer Palace.

Fourteen members of the Rathekeale Rovers gang convicted in 2016 for crimes in Cambridge, Durham, and Norwich.

In March 2016, fourteen members of a British gang known as the Rathekeale Rovers – veritable stock characters from a Horace Rumpole novel – were sentenced to prison for their roles in heists and attempted-but-bungled thefts from British museums. The gang stole small but extremely valuable Chinese objects made of jade, lapis, rhinoceros horn and other materials highly coveted inside China. Members of the gang targeted both the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge and Oriental Museum in Durham. The Rovers are well known for crimes involving theft of objects made from rhinoceros horn – but also for their association with the killing of a 4-year old rhino is a French zoo.

A porcelain sculpture and jade bowl were stolen in April 2012 from the Malcolm MacDonald Gallery at the Oriental Museum at Durham University. A judge termed the thieves “crassly inept” after they forgot where in a wasteland they had hidden their $3 million haul. The items were eventually recovered from the swampy ground.

Eighteen exceptional Chinese jade and lapis objects were stolen in April 2012 from the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge University; the stolen items were valued between $8-$23 million. The thieves were caught but the objects were not recovered.

Among those found guilty was London resident Chi Chong Donald Wong, who was described as having links to Hong Kong. Authorities believe that the £57 million worth of objects that were not recovered were sent to China, where some collectors are willing to acquire stolen objects despite their having been widely published and therefore identifiable.

The most sought-after objects are from the Summer Palace

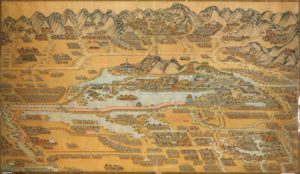

Map showing Eight Banners Brigade barracks, temples, villages, bridges, mountains, and the Summer Palace, Beijing, author unknown, after 1888. Library of Congress, Gift of Thomas Goodrich.

Many of the objects stolen from Western museums during the multi-year spate of art heists – and many of the objects most valued in the Chinese markets – have something in common: they were looted during the destruction of the Old Summer Palace in October of 1860.

It is undisputed that the Anglo-French expedition that destroyed the Yuanmin Yuan or Summer Palace was an unashamedly imperialist venture. However, the Summer Palace was initially sacked, then burned, on the order of British High Commissioner Lord Elgin in retaliation for the torture and execution of European and Indian prisoners by the Chinese. A diplomatic deputation of European officials and their retinue to the Summer Palace had been seized and then killed by Chinese officials and their mutilated bodies exposed; the murdered individuals included two official envoys and a journalist from the Times of London. Elgin decided that it would have little effect on Chinese government officials if he attacked the city of Beijing. He seems to have made a deliberate decision to harm China’s rulers where it hurt most.

The gardens were famously beautiful and what the English and French saw as retribution for the murder of diplomats, the Chinese considered a flagrant abuse of foreign power. Although Elgin ordered everything burned, the English and French soldiers disregarded his orders. They grabbed all they could and enormous numbers of looted objects came on the market in both China and Europe soon after.

These losses still rankled 150 years later, when in 2000, four objects from the Summer Palace were offered for sale by auction houses Christie’s and Sotheby’s in Hong Kong. Despite protests from the Chinese government, the sales, which included the heads of a tiger, monkey and ox from the water clock at the Summer Palace, went forward. These were three of the twelve zodiacal forms that originally decorated an elaborate clepsydra, or water clock, in the Yuanming Yuan garden of the Old Summer Palace under Emperor Qianlong (1736-1795). The Poly Group Corporation, which had been officially separated from the Chinese military just the year before, was the buyer.

The 2009 Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé sale in Paris

Bronze rabbit and rat, taken from the Yuanming Yuan 160 years ago. Featured in the sale of the collection of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé. The heads were presented to China by François-Henri Pinault in 2013.

Fast forward to the Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé collection sale after Yves Saint Laurent’s death, which included a pair of bronze heads from the same water-clock, a rabbit and a rat. The sale of these heads from the Yuanming Yuan was already highly politicized because of where the objects came from. It became even more fraught with controversy when the owner, Pierre Bergé, offered to bring the heads in person to China in exchange for a pledge by the Chinese government to honor human rights in Tibet.

Both Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé had been deeply concerned about the destruction of hundreds of Tibetan sites and monasteries in an effort by the Chinese government to eradicate Tibetan culture. Bergé saw the European looting of 1860 and the Chinese destruction of Tibetan culture as parallel events.

Chinese officials were infuriated. They said Bergé’s offer was “ridiculous.”

The Chinese government did not send an official request to intervene in the auction, held at Christie’s in Paris, but an independent team of Chinese lawyers did try to stop the sale. Their claim was rejected by a French court before the auction began. After the sale, the buyer, Cai Mingchao, a Chinese collector and auctioneer, refused to pay as a protest. He was lauded as a hero in China.

It was made clear to Christie’s that the Chinese government was unhappy with the sale of the zodiac heads. Christie’s was sanctioned by the Chinese government within hours of the sale. Christie’s management was likely aware that Chinese buyers would hesitate to buy from the auction house if it was in disfavor with the Chinese government. In 2013, François-Henri Pinault, whose company, Groupe Artémis, owns Christie’s as well as Chateau Latour, Gucci, Stella McCartney, Balenciaga, and other high-end consumer lines, presented the two heads to China as a good-will gesture.

Television and movies recharge and reinvent the trauma

Poster for the film, Chinese Zodiac, starring Jackie Chan. “Twelve heads. Five continents. One man.”

The political importance of retrieving the twelve zodiacal heads (which have also been ‘recreated’ in gold and bronze by contemporary artist Ai Weiwei), is complex and in some ways contradictory. The original heads were actually made by a Milanese Jesuit, Brother Giuseppe Castiglione. He was a young painter, trained in the Milanese style, who became a missionary and traveled to China in 1715, where he became enamored of Chinese painting. The Emperor Quianlong supported and encouraged Castiglione, who worked under the Chinese name Lang Shih-ning. The artist developed a syncretic style that blended both Chinese and Western artistic traditions. Thus, artworks made by an Italian have come to typify Chinese national heritage.

What makes these particular bronze objects important ‘cultural property’ in part arises from their exposure in popular culture. In 2005, a 24-part Chinese television series called “Palace Artist” was made about Castiglione, who was played by a popular actor from Canada, Mark Roswell, known as Dashan in China. In 2011, Jackie Chan donated replicas of the zodiac heads for an exhibition in the southern branch of Taiwan’s National Museum. The exhibition was targeted by vandals for political reasons and also criticized on the basis that replicas were not museum-worthy. In 2012 the museum removed the zodiac heads from exhibit. Chan also made a 2013 martial arts movie called Chinese Zodiac about hunting down stolen national treasures. Chan starred as Asian Hawk, directing a team of relic hunters who raced against time to find the bronze busts of 12 Chinese zodiac animals before the head of a ruthless corporation could destroy them.

Given the overwhelming attention paid to the looting of the Summer Palace, it should probably not surprise Western museums that their collections are seen as fair game. Or that some Chinese buyers see the return of artworks from colonial collections, even through theft, as a way of reclaiming their heritage. Items known to have come from the Beijing Summer Palace are particularly politically charged, and the end justifies the means, even if illegal.

The idea that you can correct history or settle a score by returning art is emotionally appealing to many. However, there was no legally sustainable claim for repatriation in the sales in Hong Kong or Paris; the objections raised were based either on the notion that all cultural property belongs in its country of origin or on the wrongful manner in which these particular bronzes were taken. Perhaps the position of Pierre Bergé is the most straightforward; intolerance for domestic dissent and repression of minorities is far more consequential to a nation’s cultural life than the temporary displacement of a few pieces of bronze statuary from a mechanical fountain.

Objects stolen in April 2012 from the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge University.

Objects stolen in April 2012 from the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge University.