Muslim Countries Surrender Principles for Chinese Cash

Seminar on Moderate Islamic Thought, Kazan Russia. courtesy Bitter Winter.

In July 2024, a fifth “International Seminar on Islamic Moderate Thought” was held in Kazan, Russia, to which ‘representatives of the international Muslim community’ were invited.[1] Guests came from Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, the UAE, Egypt, Iran, Bahrain, Qatar, and Ethiopia. Many came from countries close to China, behind whose barbed-wire borders Muslim minority peoples are trapped, crushed under an ongoing, nearly-silent genocide. All came from countries with significant Muslim populations that are sometimes in tension with their governments. All were from states with economic ties to Russia and China.

At the symposium, ‘moderate Muslim thought’ had nothing to do with actual religious belief or practice. Instead, it meant a willingness to turn religious authority over to the state.

Seminar on Moderate Islamic Thought, Kazan Russia. courtesy Bitter Winter.

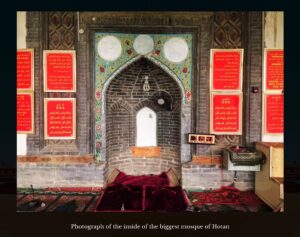

The attendees came to genuflect to the military and economic might of China and heap praise on its supreme leader, Xi Jinping. Uniformly, the attendees affirmed Xi’s right to deny basic religious and cultural rights to Uyghur, Kazakh, and Hui Muslims within China. Many speakers wore beards or turbans, a criminal act inside China. Many bore Muslim names, now prohibited as names for children in China. There was no mention at the conference of China’s admitted destruction of some 15,000 mosques, shrines and schools, of the burning of books in the Uyghur language, from poetry to translations of the Quran and hadith. There was no mention of the torture and imprisonment of teachers or of making traditional ceremonies and celebrations of weddings and births that included Muslim blessings illegal.

None of these so-called Muslim leaders expressed support for Uyghurs or other Turkic minorities currently facing extreme persecution in Xinjiang – or against the vandalization of mosques and suppression of religion in the Hui Muslim community, the most numerous and widely distributed Muslim community in China. Some delegations even offered to travel to China to proclaim that conditions for Muslims there are satisfactory.

Interior of the largest mosque in Hotan, Xinjiang, with Communist Party placards at the kibla, the direction of prayer, ‘Cultural erasure,’ ASPI, 24 September 2020.

The real goal of the conference was to define “moderate Muslims” as those who support the political agendas of China and Russia and condemn “separatism.” The alignment between China and Russia in using religious platforms for political ends highlighted a broader strategy of suppressing minority cultures and religions. Russian “State Muftis,” loyal to Putin, actively participated in the seminars. ‘Separatism’ in Ukraine was called out for criticism and Uyghurs in China and Chechens in Russia were specifically targeted as groups needing control.

The Chinese delegation came from the China Islamic Association, a state-run organization whose leaders are appointed by the Chinese Communist Party. Their claims to represent “moderate Islam” struck an especially cynical note, as ordinary Chinese Muslims, though sincere believers, have always taken a moderate and conspicuously tolerant approach toward religion. Only an infinitesimally small number of extremists have come from the region, even since the rise of Al Qaeda and the Taliban. These ‘Muslim leaders’ came to talk about economic opportunities available to Muslim nations, especially through China’s Belt and Road Initiative as a way of connecting countries with a significant Islamic presence – despite the religious repression and cultural genocide against Muslims taking place in China today.

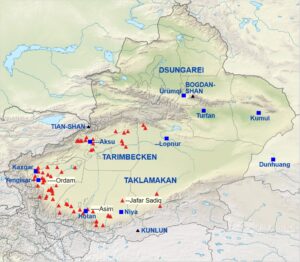

Sacred shrines destroyed by PRC government in Xinjiang, Source: Nathan Ruser, James Leibold, Kelsey Munro, Tilla Hoja: Cultural erasure – Tracing the destruction of Uyghur and Islamic spaces in Xinjiang, Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), 24. September 2020.

Although the attendees’ nations were diverse in foreign policy, they shared a common agenda, advocating for firm state control over religion and for compelling Islam to serve state interests.

The seminar was fraudulent and intended to spread disinformation – a shameful example of the manipulation of religious narratives for political and economic gain – and a reminder of how important it is to report the facts of the Chinese government’s continuing destruction of minority identity and culture.

Unfortunately, many Muslim international organizations, including the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and the World Council of Muslim Communities, are reluctant to criticize China or to defend the interests of Chinese Muslims.[2] The fulsome praise they offer to Xi Jinping’s policies in Xinjiang is in striking contrast to their positions on Palestinian rights to independence and self-determination. Instead of honoring the most fundamental teachings of Islam that Muslims constitute members of a single community, ‘umma, they have deliberately ignored the plight of Chinese Muslims. Instead they have prioritized maintaining economic and diplomatic relationships with China, despite Xi Jinping’s anti-Muslim policies.

Tourism to Cover Up Genocide

Pakistani media personnel dance at the Kazanqi folk tourism area in Ghulja, or Yining in Chinese, in Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture of northwestern China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Aug. 22, 2024.

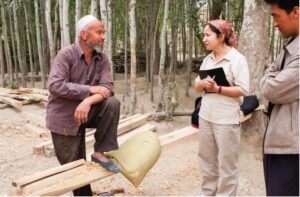

Although no Pakistan delegates were listed for the Kazan conference, a highly publicized first-time trip to Xinjiang this August by Pakistani businessmen, most of whom were ethnic Uyghurs, caused outrage among Uyghurs in Pakistan who fled Xinjiang. The visit was paid for by China’s government and resulted in numerous online postings of them dancing and visiting tourist spots, proclaiming that “Muslims of all ethnicities are living happily in Xinjiang.”[3]

Central Asian specialist Magnus Fiskesjö of Cornell University in NY has drawn attention to parallels between China’s efforts to deceive the press and public about Uyghur genocide and Nazi German efforts to showcase occupied Poland and recast it as ‘German heritage.’ Fiskesjö sums up its purpose:

“It’s about inviting people and tricking and fooling them into [seeing] this as a normal area, controlled and safe.” …” “Having suppressed all possible resistance — through a formidable surveillance apparatus, mass detention of anyone remotely suspect of pro-native sentiment, and mass forced labor for camp survivors — the Chinese government is now promoting both domestic and foreign tourism to the Uyghur region.”[4]

Cultural Heritage Destruction Expands Across China

Before and after: Yangjiazhuang mosque. Courtesy Bitter Winter.

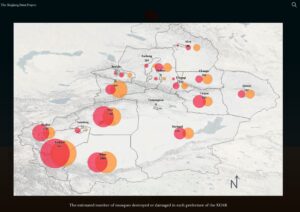

The continuing destruction of Uyghur cultural monuments is a key part of China’s policy of eradicating Uyghur identity and traditions. The last eight years of bulldozing and damage of cultural monuments continues unabated. An Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) publication estimated that “approximately 16,000 mosques in the region (65 percent of the total) had been destroyed, damaged, or desecrated, and a further 30 percent of important Islamic sacred sites had been demolished.”

A November 2023 report by the Financial Times found that the Chinese government’s crackdown on Islam has now spread throughout China.[5] Its analysis showed that out of 2,312 mosques with Islamic architectural features, three quarters have been modified or destroyed since 2018. Maya Wang, acting China director at Human Rights Watch, confirmed in 2023 that, “The Chinese government is not ‘consolidating’ mosques as it claims, but closing many down in violation of religious freedom.”

According to a Hui Muslim interviewed, “We’ve all deduced that this isn’t just about a dome,” he says. “They want to Han-ify all Muslims, to remove Islam from life . . . To stop prayer, stop religious study. To change our culture, our way of living.”

According to Cornell University fellow Ruslan Yusupov, “People feel that the government is slowly decreasing the difference between the way it handles Uyghurs and the way it handles [other] Chinese Muslims… But many think it will not come to the camps.”[6]

China’s “Strike Hard” Campaign Against Xinjiang Society

There could hardly be a worse outcome for Muslims across China than to be subjected to the repression, the human rights violations, and the destruction of historical monuments by the Chinese government in Xinjiang.

ASPA’s Xinjiang Data Project, estimated Mosques damaged and destroyed, January 10, 2020. Courtesy Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

The Chinese government has used repressive tactics to suppress Uyghur and other minority Muslim groups since the early 20th century. In the last decade, however, it has adopted a policy of complete eradication of all cultural expression except what it deems useful as a show for tourists. Starting in 2014, a “Strike Hard Campaign against Violent Terrorism” extended state control over Uyghur religious, community and family life.

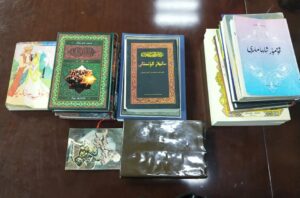

China’s systematic efforts to suppress Uyghur culture involve the mass detention and prosecution campaigns targeting not only community leaders but also ordinary citizens. Especially since 2017, routine social events, including family gatherings with religious elements, have been criminalized. Uyghur and Kazakh communities have been forced to purge all books in languages other than Chinese and all religious images and objects in order to avoid persecution and arrest. The state’s narrative portrays such common Uyghur cultural and religious practices as threats to social order, justifying extremely harsh measures.

A campaign of mass detentions and prosecutions has targeted Uyghurs and Kazakhs. Over 615,000 people have been formally prosecuted, reflecting a significant shift from ‘re-education camps’ to mass imprisonment. Criminal prosecutions increased dramatically in 2017, with Xinjiang accounting for a disproportionate share of national cases.

2024 Increased Retroactive Criminalization

Leaked Xinjiang police files. Young man in tiger chair.

China has retroactively applied new laws to activities that were previously legal. The Chinese government has criminalized ordinary Islamic practices, framing them as actions of “evil gangs.” Possession of Uyghur and Kazakh books and religious texts, including formerly approved official textbooks, are now used as evidence of extremism. Data from court cases and internal documents reveal widespread use of torture and coercion to extract confessions to committing anti-state activities such as reading Uyghur or Kazakh books, watching foreign videos or listening to criticisms of the Party.

A single case like that of Nurlan Pioner demonstrates the severity of abuse of individuals and the systematic nature of the repression. An important essay published in 2024 by Darren Byler, an anthropologist and author of several books on Xinjiang[7] describes the horrific persecution of a state-appointed Kazakh religious and community leader, Nurlan Pioner, for community religious activities that were perfectly legal just a few years before, but which are now deemed serious “crimes.” Pioner officiated at marriages, circumcisions, and funerals, had taught lessons on religion 17 times, had helped groups of local women, who lacked a female religious leader, to learn to pray at home since they were not always welcome in mosques, and gently helped the elderly at the end of life.

Leaked Xinjiang police files. Detainees preparing to recite.

When he was arrested in June 2017, Pioner was only fifty years old, healthy and active, serving as a village representative in the Jimunai County People’s Congress and known for his leadership in the Kazakh community. He was a scholar, able to read Chinese and Arabic in a community where most were illiterate, as he had studied religion in a Chinese, state-run Islamic training center. In sum, he was the most respected and beloved member of his community.

Fourteen months after being taken into custody, his sister-in-law Sholpan Amirkhan and her aunt were able to attend a bail hearing for him in Jimunai County People’s Court, Xinjiang. They watched as Pioner was carried into the courtroom, almost unrecognizable. Byler writes:

“He was gaunt, and a fetid smell followed him. When she shouted his name, she did not see any recognition on his face. He trembled, barely able to maintain a sitting posture as the guards settled him into the seat in the defendant’s cage for a bail hearing… now, his limbs paralyzed, he sat in his own urine in the courtroom.”

Leaked Xinjiang police files. Detainees under guard watching speech. Note club held by guard in back.

Pioner was arrested as part of China’s broader crackdown on ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, accused of leading the Kazakh community into extremism. He was accused of leading nikah (traditional wedding) ceremonies for 39 couples, 13 of whom had not received a state marriage license before the ceremony. In one instance, Pioner had conducted a marriage and divorce without state approval. He was accused of “gathering a crowd to disturb social order,” “using extremism to undermine law enforcement,” and “illegal possession of items propagating extremism and terrorism,” that is, books. The books now deemed criminal to possess were all legally available in circulation just a few years ago – they were an already censored Uyghur translation of hadiths, Garden of the Righteous, used widely until its authors’ arrest in 2017, a book of quotations from Indian imams, also formerly widely available, and a basic book of Islamic education.

At his hearing, Pioner was sentenced to 17 years imprisonment. Byler reports how, shocked and appalled, Amirkhan whispered to her aunt, “it would be better if they just killed him.”

Leaked Xinjiang police files. Guards inspecting basement cells.

Months later, Amirkhan was able to smuggle a copy of the official verdict given to Pioner’s family when she escaped to Kazakhstan, revealing how routine Islamic practices were criminalized. It not only described what books ‘fostered extremist thought,’ but also described how homes and phones were searched for extremist content (such as viewing non Chinese websites, any mention of prayer or Islam, who drove in which cars to religious events, and which young people followed traditional customs such as fasting during Ramadan).

It is illegal to teach children religion or for people under 18 to go to a mosque in China. Extremely stiff prison sentences are given for teaching religion to their children. Heyrisia Memet was sentenced to ten years in prison in 2014 for providing religious instruction to teenagers in her village at the request of her neighbors. Released briefly, she was resentenced to another 14 year term in June for the original offense.[8] Two others from her village were also resentenced for their previous supposed crimes; they had been accused of listening to audio recordings or watching videos, although they had been released for over a year and there were “no problems” according to their village security director. They each received new 18-year sentences because their previous “education” had not been sufficient.

The Vanishing Role of Books in Uyghur Culture

World renowned Uyghur folklorist Rahile Dawut conducting research at a mazar shrine, ca. 2005. She “disappeared” in 2017. In 2023, it was announced that she had received a life sentence. Her ‘crime’ is unknown. (Screenshot from Lisa Ross 2019)

Chinese government policy on education and access to information is clearly intended to limit free access to information and to erase minority histories. It seeks to deprive the Uyghur population of both its current cultural elite and potential future leadership and to remove the custodians of cultural heritage from communities. The State Department’s Office of International Religious Freedom reported in May 2021 that the whereabouts of “hundreds of prominent Uyghur intellectuals, religious scholars, cultural figures, doctors, journalists, artists, academics, and other professionals… remained unknown.”

A 2021 study by the Uyghur Human Rights Project details how over 300 noted intellectual and cultural producers including folklore expert Dr. Rahile Dawut, former Xinjiang University President and noted geographer Tashpolat Teyip, Medical University President Halmurat Ghopur, poet Addujagir Jalaleddin, and pop singer Ablajan Ayup have all disappeared into the camps and prisons.[9] So have the linguist Arslan Abdulla, and the folklorist Abdukerim Rahman. Editors of previously approved textbooks on Uyghur history have been given life sentences and “suspended” death sentences for “inciting ethnic hatred” and “fabricating separatist materials.

Screenshot from pop singer Ablajan Ayup’s video of song, “Dear Teacher” about the importance of learning in school.

At a day celebrating poetry worldwide, exiled Uyghur poet Isa Elkun asked for fellow poets currently jailed in Xinjiang to be remembered:

- Abduqadir Jalalidin: Poet and scholar detained without reason; notable for his poem “No Road Back Home.”

- Perhat Tursun: Contemporary poet sentenced to 16 years in prison.

- Gulnisa Imin Gulkhan: Female poet sentenced to 17.5 years for “spreading thoughts of separatism.”

- Ablet Abdurishit Berqi: Academic and poet sentenced to 13 years.[10]

In 2015, before the government crackdown in Xinjiang, In 2015, Uyghur youth in Urumqi frequently read Uyghur historical novels and travelogues in state-run bookstores. Reading offered an escape and connection to other cultures and times. Among Uyghurs, books are highly respected, even revered objects; burning or destroying books is considered an act of desecration.

Books seized by the Urumqi Public Security Bureau during home inspections in Xinjiang in 2018. Courtesy of Yael Grauer via ChinaFile

A local Uyghur bookseller was also accused of “fostering extremist thought” in Pioner’s case. Legal defenders of the bookseller, Tokhti Silam, have argued that the alleged crimes occurred before relevant laws were enacted (between 1994-1995 and 2011-2015). The lack of legal provisions during these periods meant there was no awareness of legal responsibilities.

After the house searches and arrests for ownership of Uyghur and Kazakh texts, the local bookshops shelves were stripped of all non-Chinese works. Families began purging their homes of any books related to religion and Islamic objects, in order to avoid arrest and prosecution. Byler reports how a family burned all their books, page by page, for fear that they might be tracked down if they tried to throw their books away.

Today, Uyghur- and Kazakh-language books have begun to reappear in Xinhua Bookstore, but they are mostly translations of Chinese texts, evidence of continuing government control of cultural expression.

Attendance at Traditional Weddings Now a Crime

Uyghur men dancing, hand-colored photograph from the Svesnska Missions collections. The Mission Covenant Church of Sweden (MCCS) was active in the oasis towns of Kashgar, Yengi-Hisar and Yarkand in East Turkestan (Xinjiang) between 1892 and 1938.

A traditional Muslim wedding in Xinjiang in 2015 would be conducted by a mullah and include a Quranic blessing, followed with celebratory activities such as feasting, music, and dancing. These events were important for transmitting Islamic traditions and were routine, even during periods of political sensitivity like the Maoist era.

By 2017, such celebratory social gatherings could be labeled as “gathering a crowd to disturb social order.”[11] After that time, a village mullah could face a five year prison sentence for reciting such blessings. For young men from local villages, a wedding was an opportunity to get a look at unmarried girls who might be potential brides and a chance to show off their dance skills. Now, attending a wedding where blessing were given meant they could be accused of receiving “illegal religious knowledge,” leading to potential re-education camp detention. A quieter wedding without music and dancing but which included traditional prayers was even more suspect. Charismatic mullahs who led such prayers were seen by locals as community leaders but were labelled as extremist ringleaders by state authorities.

Systematic Repression and Escalation of Detention and Imprisonment Since 2017

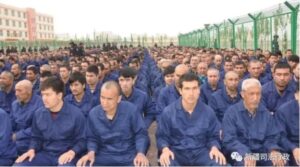

Detainees in the real brainwashing camps, where native languages are forbidden. Photo from Chinese social media; taken down after circulating outside China)

Chinese state actions have fundamentally altered cultural and religious life in Xinjiang. While the frequency of detention in internment camps may have decreased, control remains through much-expanded formal imprisonment and cultural regulation.

China’s government issued new and even harsher regulations in 2024 aimed at erasing traditional culture and Muslim identity in ethnic minority regions. The regulations are part of a broader effort to Sinicize Uyghur religious practices and align them with state ideology. The new 2024 regulations include:

- Stricter control over religious practices and institutions.

- Imposition of architectural guidelines for places of worship to reflect Chinese characteristics.

- Restrictions on religious education, allowing only government-approved teachings.

- Increased surveillance and monitoring at the grassroots level.

Human Rights Watch and other organizations classify these actions as potential crimes against humanity.

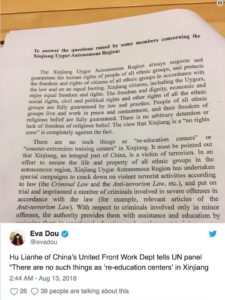

Official letter stating that “There are no such things as ‘re-education camps’ in Xinjiang.

The reeducation campaign that began in 2017 led to mass detentions, of about one-tenth of all adult Uyghurs and Kazakhs in Xinjiang, primarily in so-called education centers. In fact, these were high-security concentration camps in which brutal torture and rapes were frequent and withholding food, sensory deprivation and brutal brainwashing techniques were standard treatment for all.

Starting in 2018, there was a shift from internment camps and pretrial detention to mass imprisonment. Data from court cases and internal documents reveal extensive use of torture and coercion to extract confessions and cause deliberate suffering to prisoners.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) reported in 2020 in its Xinjiang Data Project that although China’s government claims the ‘educational’ concentration camps are being closed, construction of new camps continues despite government claims that their function was winding down.

Human Rights Abuses: The Uyghur people are the most imprisoned people in the world.

Xinjiang, Kashgar cultural heritage official accidentally included in a staged visit for foreign journalists, to a make-believe camp. (From Radio Free America 2019.)

Uyghurs are the most imprisoned people in the world. Over 615,000 people have been formally prosecuted in Xinjiang since 2017. A comparison of average annual prosecutions from 2014-2016 (about 41,700 per year) to 2017, where prosecutions jumped to 220,000, shows a 437% increase.

There is an extraordinarily high level of arrests and prosecutions in Xinjiang compared to elsewhere in China. Xinjiang prosecutions constituted 15% of all prosecutions in China in 2017 despite only having 1.8% of the national population. The fact that there has been a decline in prosecutions after 2017 is not a relaxation in policy but is likely due to the high number of already detained individuals and the very lengthy sentences imposed, removing prisoners from society for decades for nonexistent ‘crimes.’ Despite the decline, Xinjiang still accounted for 6% of all prosecutions in China from 2017 to the end of 2022.

Officials oversee a ribbon-cutting ceremony at the opening of a political ‘re-education camp’ in the Xinjiang’s Korla city, in June 2018. Korla city website.

The statistics on imprisonment are alarming. Despite forming only 1.8% of citizens in China, Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples constitute one-third of China’s total prison population. At least 1 in 26 non-Han citizens in Xinjiang have been incarcerated.

The U.S. based Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP) reports 3,814 Turkic people jailed per 100,000 in Xinjiang from 2017 to 2022, compared to 80 Han Chinese per 100,000. This is by far the highest rate of imprisonment in the world. It dwarfs that of El Salvador, previously known for its high imprisonment rate of 1,086 per 100,000 citizens.

Researcher Peter Irwin’s 2021 survey for UHRP revealed that at least 1,000 imams and mullahs have been detained since 2014. This is likely a significant undercount, as internal police documents from Urumqi show hundreds more religious figures detained. These detentions were often justified by citing to illegal religious activities or euphemisms like “disturbing social order” or “extremism.”

Village women targeted for religious ‘crimes’

Women convicted and sentenced to lengthy prison terms in Xinjiang for studying Islam.

At the same time that China’s government characterizes women as victims of ‘extremist’ male influences, it does not hesitate to imprison and torture elderly women, mothers, and female students. The charges made against women are even more implausible and the sentences even more disproportional than those against men – both because women’s everyday private religious practice has been criminalized and because imprisoning female and elderly family members is a tool used to coerce Uyghurs abroad to return – and then imprison them as well, simply for having studied or worked abroad.

Historically the government has had less oversight of women’s religious practices because in many communities, women do not attend mosques but pray in their homes. A common pattern in Xinjiang today is to arrest elderly women, some over 80 years old, for past religious learning, often for taking part in religious activities 20-30 years ago. There are a number of instances involving women who were as young as five or six at the time that they received so-called extremist religious education.[12]

China now imposes retrospective criminal sentences for actions that were not illegal at the time they were committed, such as studying the Quran or wearing a hijab. (The ban on any veiling also confines elder and pious women in their homes if their personal faith does not permit them to appear in public without a head covering.)

Büwi are female religious mem who carry out various religious and quasi-religious activities for other women. As early as 2012 the government attempted to register and regularize activities of büwi, initiating a required four-day course in instruction on washing the bodies of the dead. Traditional study could take years, and included “lessons on reciting the Quran, leading prayers and zikr, reciting Uyghur language prayers and praise songs (hikmet and monajat), conducting hetme and tünek rituals, as well as the mechanics of preparing the body for burial.”[13]

Female religious leaders who teach or lead prayers in village communities, büwi, are specifically targeted. Since 2017, ninety-one women from a single county were identified and imprisoned – because they were officially registered as büwi. The removal of female religious leaders from communities has a drastic, detrimental effect on community cohesion and Uyghur identity. Likewise, criminalizing children’s religious education accelerates the breakup of traditional communities, making it impossible for parents to instill values or even to speak with any frankness to their own children.

Where is my family?

Muherrem Mettursun, left, 49, was detained in 2021; her 68-year-old mother, Tajinisa Yimin, center, was detained on terrorism-related charges in 2021; and her father, Nuri Mettursun, right, was 67 when he was arrested in 2017. He died five months into a five-and-a-half-year sentence. Photo: Courtesy of Nurmemet Mettursun.

The families of Uyghur activists are specifically targeted in China. In June 2018, President of the World Uyghur Congress (WUC) Dolkun Isa was told that his mother Ayhan Memet, 78, had died two months earlier while in detention at a “political re-education camp.” He had not known where or how she was detained.[14] He said:

“I don’t know how to express my sorrow over her death and my anger toward China’s treatment of her… Killing one’s mother to retaliate against her son’s peaceful human rights activism is the most cowardly form of retaliation by any authoritarian government. I will solemnly mourn her death and continue to peacefully fight for the legitimate rights of the Uyghur people with dignity…”[15]

Activism of any kind by Uyghurs throughout the diaspora can result in horrendous retribution against their families in order to silence them. Nurmemet Mettursun, a doctor who immigrated long ago to Istanbul, not only mourns the loss of his father following his death in detention, but has no way of knowing how his 49-year-old sister, Muherrem Mettursun and his 68-year-old mother, Tajinisa Yiminare are faring in prison. His own wife and two children have simply disappeared.[16]

The late Nuri Mettursun. Photo: Courtesy of Nurmemet Mettursun

Coerced returns to China by students and workers abroad does not appear to protect family members – rather the reverse. Leaked documents now show that dozens of promising Uyghur and Kazakh students have returned from abroad only to be sentenced to lengthy prison terms – for having studied or worked abroad. The case of Bagdat Akin, a Kazakh exchange student, was not unusual. He was detained upon returning to Xinjiang from Egypt. His handwritten sentencing appeal describes severe interrogation tactics, including beatings, sleep deprivation, and psychological torture by forcing detainees to hear their relatives’ screams. He was not alone; there are consistent reports from former detainees confirming the prevalence of torture and of hearing screams during interrogations.

A Chinese government manual leaked to the New York Times directed officials to tell students returning for holidays from other towns in China to find their parents gone, that internees were not criminals but “Their thinking has been infected by unhealthy thoughts.” Students were instructed that even grandparents and the elderly could not be spared from reeducation in the camps. “Freedom is only possible when this ‘virus’ in their thinking is eradicated and they are in good health.” [17]

Where are my children?

Uyghur girl in Kashgar, in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. T striped clothing material is ikat dyed abr fabric, traditionally worn by Uyghur women.15 August 2008, photo Gusjer from Aranjuez, Spain, CCA-SA 2.0 Generic license.

According to the U.S. State Department, at least 880,000 Uyghur children have been placed in locked boarding schools.[18] Children as young as toddlers – 14 months old – whose parents are detained or in prison or forced-labor factories are denied guardianships by grandparents and other relatives. They are deemed a “special needs category” to be put in “centralized care.”[19]

The U.S. Department of State, China 2021 Human Rights Report, 75, states,

“The detention of an estimated one million or more Uyghurs, ethnic Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and other Muslims in Xinjiang left many children without caregivers. While many of these children had relatives willing to care for them, the government placed the children of detainees in orphanages, state-run boarding schools, or “child welfare guidance centers,” where they were forcibly indoctrinated with CCP ideology and forced to learn Mandarin Chinese, reject their religious and cultural beliefs, and answer questions regarding their parents’ religious beliefs and practices.” … “In Hotan some boarding schools were topped with barbed wire.”[20]

The Chinese government has promoted a specific narrative on Uyghur population growth over the last decade that describes population growth as “excessive” and links it to religious extremism, “splittism” or separatism, and national security threats.

Leaked documents from 2019 revealed plans for a mass sterilization campaign targeting rural counties in the southern Uyghur Region. Leaked data already shows significant declines in birth rates in parts of the Uyghur Region.

Chinese state propaganda photo of an “orphanage” for children confiscated from Uyghur concentration camp detainees, to deny them their culture and convert them into Chinese. (From Chinese social media).

Multiple government policies target Uygur and other minority birth rates, including through a Special Action Plan of the ‘Two Thorough Investigations’ of Illegal Births.’ Counties are mandated to enforce intrusive birth control measures. These policies have resulted in planned sterilization or IUD placement for 80% of women of child-bearing age in certain Uyghur-concentrated prefectures.

There is a political and anti-terrorism component to even policies on birthrates, stating that “religious extremism begets re-marriages and illegal extra births.” Locking people of marriageable age into concentration camps and prisons and sending young women away to forced labor factories across China are also components of “de-extremification” policies and seen as an opportunity to reduce religious influence on family planning policies.

Where is my home? Name changes in Xinjiang villages.

Xinjiang, Uyghur man, Sunday market, Kashgar, 3 December 2006, CCA-SA 2.0 Generic license, Photo flikr.

Recently, even place names have been targeted in anti-religious and anti-minority culture political campaigns. Chinese authorities in Xinjiang have systematically changed hundreds of village names with religious, historical, or cultural significance to Uyghurs, replacing them with names reflecting Chinese Communist Party ideology.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) identified about 630 villages where names were altered to erase Uyghur cultural and religious expressions. HRW’s research involved scraping village names from the National Bureau of Statistics of China from 2009 to 2023. Out of 25,000 villages in Xinjiang, about 3,600 had name changes during this period; 630 of these changes targeted Uyghur cultural and religious terms.

Village names were altered to take out religious terms such as “Hoja” and “haniqa” and shamanistic terms such as “baxshi.” So were names related to Uyghur history, referring to kingdoms, leaders, and political titles, for example, “orda,” (horde) “sultan,” “beg” were replaced. Terms indicating Uyghur cultural practices, like “mazar” (shrine) and “dutar” (musical instrument), were also changed.

Xinjiang, Kebab stand at Uyghur market, 11 September 2005, photo by Todenhoff, CCA-SA 2.0 Generic license.

Thus, “Two-Stringed Lute” village became “Red Flag village.” “White Mosque” village became “Unity village.” “Sufi Teacher’s Creek” village became “Willow village.”

The renaming has caused practical difficulties for villagers, including issues with government services as well as emotional distress due to the loss of cultural heritage. Personal testimonies indicate a deep impact of these changes –removing a last vestige of local identity – on the Uyghur community’s sense of belonging.

This petty form of cultural destruction may be less impactful than making it illegal for Muslims citizens to give their children Muslim names. In terms of cultural heritage destruction it may not compare to the bulldozing of 15,000 ancient mosques and shrines, and the imprisonment of multiple generations of scholars and rewriting of the history of a once independent nation.

An Uyghur home where the supa, a traditional oven, is being destroyed on order of the government. (From Chinese social media, captured by Timothy Grose; cf. Introvigne 2020)

But it is very personal, and like all the repressive actions of the Chinese government, a clear violation of Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which China has signed but not ratified, that protects the rights of ethnic, religious, and linguistic minorities to enjoy their culture and use their language. China stands in violation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, and every other international convention protecting human beings’ fundamental rights to life and liberty.

These are formal ways of identifying China’s crimes. There are other ways of putting it. In an article on China’s tourism propaganda to counter tales of genocide, the author quotes analyst Anders Corr, who simply says:

“They’ll try out some Uyghur actors to act happy, and they will try out Uyghur dancers to look happy and tell them to smile, but if [they] don’t smile wide enough, [they] are sent to concentration camps.”[21]

Demonstration for Uyghur rights, Berlin, 19 January 2020, Photo by Leonhard Lenz, CC0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Cultural heritage is not just about archaeology or monuments or statues. This article notes only a few of the ways in which China’s government and Xi Jinping’s policies have tried to destroy Uyghur and Kazakh culture, to erase it from Muslim peoples’ own memories.

So far, the world is doing little to prevent a repeat in China of the worst horrors of the twentieth century in Europe. Is another vulnerable, innocent people’s whole identity to be stolen from them? What can they know of family, of community, of weddings or poetry or music, of simply being in the world, when every piece of their identities is taken away, in bits, and buried, burned, or thrown away.

The cruelty, brutality and utter lack of mercy shown to China’s Muslim minorities is heartbreaking. It is unforgivable. Since 2017, the Chinese government has only escalated its campaign against Uyghurs. The burning of books, elimination of religious ceremonies, even changing village names are part of a broader effort to erase Muslim culture under a false guise of combating extremism. The UN and foreign governments including the United States have condemned China’s policies in Xinjiang and imposed sanctions, but it is not nearly enough. China’s government must be held accountable for every wrong.

See also:

[1] Ma Wenyan, “A Chinese-Russian Fraud: Kazan’s “International Seminar on Islamic Moderate Thought,”” Bitter Winter, August 15, 2024, https://bitterwinter.org/a-chinese-russian-fraud-kazans-international-seminar-on-islamic-moderate-thought/

[2] Abdulhakim Idris, “Muslim-Majority Countries’ Complicity in the Uyghur Genocide,” The Diplomat, December 2, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/12/muslim-majority-countries-complicity-in-the-uyghur-genocide/

[3] Gulchehra Hoja, “Pakistan-based Uyghur businessmen praise China during Xinjiang visit,” Radio Free Asia, August 29, 2024, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/pakistan-backed-businessmen-praise-china-08292024190606.html.

[4]Uyghar, “China is borrowing Nazi’s ‘genocide tourism’ practices in Xinjiang: scholar,” Radio Free Asia, August 27, 2024, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/china-borrowing-nazis-genocide-tourism-practices-xinjiang-08272024162026.html

[5] FT reporters, “How China is Tearing Down Islam, Financial Times,” November 26, 2023, https://ig.ft.com/china-mosques/

[6] Id.

[7] Darren Byler, “How China Made Xinjiang’s Ceremonies Illegal, Retroactively applied laws are used to prosecute Muslim community leaders,” Foreign Policy, March 8, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/03/08/china-xinjiang-uyghur-muslims-weddings-human-rights/.

[8] Shohret Hoshur, “Uyghur woman resentenced for teaching youth the Quran,” Radio Free Asia, June 18, 2024, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/woman-re-sentenced-teaching-youth-quran-06182024140408.html

[9] Abdullah Qazanchi, contributions by Abduweli Ayup, ‘The Disappearance of Uyghur Intellectual and Cultural Elites: A New Form of Eliticide,’ Uyghur Human Rights Project, December 8, 2021, https://uhrp.org/report/the-disappearance-of-uyghur-intellectual-and-cultural-elites-a-new-form-of-eliticide/

[10] Ruth Ingram, “Uyghurs Bravely Resist Oppression Through Poetry,” Bitter Winter, March 5, 2024, https://bitterwinter.org/uyghurs-bravely-resist-oppression-through-poetry/

[11] Darren Byler, “How China Made Xinjiang’s Ceremonies Illegal.” March 18, 2024. The author notes that the Xinjiang Communist Party Committee’s list of “75 Signs of Extremism” in 2014 included attending cross-county religious events and holding weddings without music or dancing.

[12] Dr. Rachel Harris and Abduweli Ayup, “Twenty years for learning the Quran,” UHRP, February 1, 2024, https://uhrp.org/report/twenty-years-for-learning-the-quran-uyghur-women-and-religious-persecution/

[13] Id.

[14] Shohret Hoshur; Joshua Lipes, “Uyghur Exile Group Leader’s Mother Died in Xinjiang Detention Center.” Radio Free Asia, July 2, 2018. Translated by Alim Seytoff. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/mother-07022018164214.html

[15] Id.

[16] Ruth Ingram, Uyghurs in China: The Most Heavily Jailed Group in the World,” Bitter Winter, June 28, 2024, https://bitterwinter.org/uyghurs-in-china-the-most-heavily-jailed-group-in-the-world/

[17] Kuo, Lily, “‘Show no mercy’: leaked documents reveal details of China’s Xinjiang detentions”. The Guardian. 17 November 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/nov/17/show-no-mercy-leaked-documents-reveal-details-of-chinas-mass-xinjiang-detentions.

[18] U.S. State Department’s Office of International Religious Freedom, 2020 Report on International Religious Freedom: China-Xinjiang, Executive Summary, May 12, 2021, https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-report-on-international-religious-freedom/china/xinjiang/.

[19] In one township, over 400 minors had both parents in some form of internment, and many more a single parent. Many children are reportedly kept in appalling conditions. See ‘Break Their Roots: Evidence of China’s Parent-Child Separation Campaign in Xinjiang,’ Journal of Political Risk, Vol. 7, No. 7, July 2019, https://www.jpolrisk.com/break-their-roots-evidence-for-chinas-parent-child-separation-campaign-in-xinjiang/

[20] United States Dept. of State, CHINA, 2021 Human Rights Report, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/3136152_CHINA-2021-HUMAN-RIGHTS-REPORT.pdf

[21] Uyghar, “China is borrowing Nazi’s ‘genocide tourism’ practices in Xinjiang: scholar,” Radio Free Asia, August 27, 2024, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/china-borrowing-nazis-genocide-tourism-practices-xinjiang-08272024162026.html

Xinjiang, painting for tourist sale of happy Uyghurs in Kashgar, photo by Raki Man, 3 August 2011, CCA 3.0 Unported license.

Xinjiang, painting for tourist sale of happy Uyghurs in Kashgar, photo by Raki Man, 3 August 2011, CCA 3.0 Unported license.