UPDATE! The CPAC hearing on renewal of MOUs with Italy, Chile and Morocco and a new proposed MOU with Vietnam is now scheduled for May 20, 2025! Despite the manifold changes at the Department of State, this particular committee’s operational staff and its appointed members, representatives of the fields of archaeology, museums, the art trade and the public interest appears to have continued unchanged.

The public may provide written comment in advance of the meeting and/or register to speak in the virtual open session scheduled for May 20, 2025, at 2:00 p.m. EDT.

How to submit written comments: After weeks of problems and broken links on the Federal Register site, we’ve been informed that it is now working. Use the following link:

https://www.regulations.gov/document/DOS-2025-0003-0001. Please follow the prompts to submit written comments. Written comments must be submitted no later than May 13, 2025, at 11:59 p.m. EDT.

How to make oral comments: Make oral comments during the virtual open session on May 20, 2025 (instructions below). Requests to speak must be submitted no later than May 13, 2025, at 11:59 p.m. EDT.

Committee for Cultural Policy: Written Testimony submitted to Cultural Property Advisory Committee, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, U.S. Department of State, on the Request for Renewal of Import Restrictions from the Republic of Chile, Submitted January 23, 2025 for Hearing May 20, 2025

The Committee for Cultural Policy[1] submits this testimony on the Request from the Republic of Chile for renewal of its 2020 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the United States, pursuant to the 1983 Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act[2] (CPIA).

The Cultural Property Advisory Committee at the Department of State (CPAC) will meet February 4-6, 2025 to vote on a 5-year proposed extension of U.S. import restrictions on cultural items from Chile, whose original agreement dates to October 7, 2020.

The Chile Request

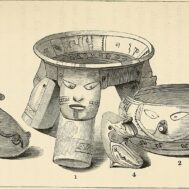

Chile has not provided any public summary of its renewal request or given reasons for the necessity of renewal of its cultural property agreement with the United States. Chile’s original request, 5 years ago, likewise failed to provide any information on the scope of restrictions and the reasons for which they are sought. Nor did it provide evidence of looting beyond the statement that “the most commonly trafficked objects are ceramic vessels and, to a lesser extent, stone, textile and metal artifacts”, or for the existence of a significant U.S. market.[3] A finding of these facts is necessary in order to meet the criteria for import restrictions under the U.S. law.

The first Chilean request itself failed to argue that Chile met any of the four specific criteria Congress set as justification for import restrictions. Yet when the Chilean MOU was signed and a Designated List of items restricted from import was issued, the list included virtually every known object from every period of Chile’s archeological history – a full five pages in the Federal Register, covering every conceivable object from mummified remains to pottery to textiles, as well as items made of metal, wood, bone and shell, from 31,000 BC to 1868 CE.[4]

Chile Cannot Meet the Requirements for an Agreement Under the Cultural Property Implementation Act

Failure to Substantiate Claims of Looting and Efforts to Protect Heritage

In the last five years, there has not been reporting of significant looting or seizures of antiquities – either through lack of looting or lack of police interest in halting or reporting it. Some paleontological materials were seized between 2007 and 2017, but these fall outside the scope of CPIA. Vague assertions about looting and seizures, unsupported by concrete data, and the numerous failures in archeological protection listed below violate the requirements under 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(A) and (B) to show the cultural patrimony is in jeopardy and that the source nation has taken measures consistent with the UNESCO 1970 Convention to protect its cultural patrimony.

Lack of evidence for a U.S. market in looted Chilean materials

There is likewise a lack of evidence for a current U.S. market for Chilean antiquities. Searches of major auction houses (e.g., Sotheby’s, Christie’s) show not a single sale of Chilean ancient or ethnographic objects – not just in the U.S., but worldwide, going back to 2015.[5] The request thus fails to demonstrate that U.S. import restrictions would significantly deter looting or trafficking under 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(C).

No traveling exhibitions or cultural exchange

The CPIA requires proof that restrictions are consistent with international cultural interchange, but Chile fails to meet this requirement under 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(D). Chile has not shown evidence of a commitment to share its culture with the world, instead relying on the world coming to Chile. There have been few cultural exchange programs or international exhibitions that promote its heritage in the U.S. No traveling exhibition of any of the ancient works on the 2020 Designated list has come to the U.S. The only exhibitions have been of the work of contemporary artists.[6]

Insufficient self-help measures and indifference characterize Chile’s government

The CPIA requires countries seeking MOUs to demonstrate significant self-help measures, which Chile has not adequately addressed. Regrettably, Chilean governmental cultural institutions have not given recent attention to much needed archaeological excavations except in conjunction with development projects[7]– nor have they made substantive efforts to prevent the sale of artifacts within the country to domestic collectors of archaeological and historical items.

Since Chile fails to meet the criteria for an agreement under the Cultural Property Implementation Act, the Committee for Cultural Policy urges Education and Cultural Heritage at the Department of State NOT to renew the 2020 MOU and instead to undertake meaningful assistance to archaeological and conservation organizations and institutions in Chile to encourage archaeological protections and engage collaboratively with the Chilean public, especially indigenous communities in archaeologically rich regions as described below – for none of Chile’s problems will be resolved by renewed import restrictions.

The Status of Archaeological Work in Chile

Santiago’s Metro excavation is Chile’s largest ‘archeological’ project.

The most successful archaeological project in Chile in decades was undertaken purely as a by-product of infrastructure development. Nonetheless the digging of Santiago’s Metro has reaped significant archaeological benefits since it began in 1969.[8] The archaeological excavation work has undertaken by different teams of archaeologists, supported by excavators, conservators, physical anthropologists, geologists and surveyors, far more intensively since 2020. The excavations for the Metro lines have yielded more than 181,000 archaeological pieces from sites showing human occupation, primarily by hunter-gatherers some of which date to 9,000 BCE.

Consuelo Carracedo, archaeologist of Metro de Santiago, explained, “These findings are of great relevance to the cultural heritage of our country, since on the site it is possible to recognize one of the most complete chronocultural sequences in Central Chile, which would cover the last 11,000 years to the present.”

Extraordinary Damage to Atacama Desert Geoglyphs

The Metro project, although originally conceived solely for infrastructure development, is Chile’s primary archaeological success. Weighed against this is Chile’s failure to preserve and protect the Atacama Desert geoglyphs and other important sites.

The Chilean geoglyphs, created by ancient civilizations over 1,000 years ago, are best viewed from high altitudes, revealing their intricate designs and scale. Made by clearing darker soil to expose lighter sand beneath, these geoglyphs were integral to ancient llama caravan routes and pilgrimages over 3,000 years ago. Their cultural and historical significance rivals that of Peru’s UNESCO-listed Nazca Lines, but Chile’s government has failed to give them formal recognition and protection.

Despite their cultural significance and similarity the Nazca Lines, the Chilean geoglyphs remain under the weak protection of a loosely enforced National Monuments Law, leaving them vulnerable to the most callous destruction. The Atacama Desert Foundation has reported significant and continuing damage to ancient geoglyphs in the Alto Barranco area of the Tarapacá region, caused by motorcycles, 4×4 vehicles, and other off-road activities.[9] Off-road riding is still a popular activity in the region, exacerbating the threat to their preservation.

Between 2009 and 2015, the annual Dakar Rally, which had temporarily relocated from Africa to Chile and Peru, sent hundreds of vehicles through the Atacama Desert. This event caused extensive damage to at least 318 archaeological sites, including geoglyphs that are over 1,000 years old.

The Atacama Rally, a local off-road competition, has denied responsibility for the continuing damage. Yet the absence of robust government oversight enables such events and activities to continue endangering these irreplaceable cultural monuments. Their destruction is the result of complete indifference to damage by tourists, party-goers and even Chile’s military. In the past, some geoglyphs were used as targets for Chilean military bombing training exercises, reflecting the government’s complete indifference to the need for protection.

Archaeologist Gonzálo Pimentel has described the destruction as the worst ever seen for these geoglyphs, emphasizing that restoration efforts would be nearly impossible without immediate and effective protective measures. He has also warned that further incidents are inevitable unless strict protections are enforced.[10]

Instances of Conflict Between Development and Archaeological Preservation in Chile

In Chile as in other developing nations, there has been a shift in archaeological practice from scientific conservation to archaeology as a companion to development activities, inevitable given the influence of transnational governance and the role of multilateral development banks in shaping heritage management. This has brought forward conflicts surrounding heritage rights and the impact of global climate change. There has been considerable tension between development goals and cultural preservation in Chile.[11]

A few examples underscore the persistent conflict. Santiago de Chile has experienced significant urban sprawl since the 1970s due to policies resulting in unchecked horizontal and vertical growth. The absence of sustainable urban and heritage conservation policies has exacerbated the deterioration and loss of residential and industrial historical buildings in Chile’s cities. Architectural heritage has largely been overlooked in urban development, as evidenced in the Estación Central commune, an area historically tied to the city’s first train station from the mid-19th century.[12]

Many non-listed historical sites in Estación Central have been demolished due to weak legal protection and permissive construction regulations. In recent years, high-density, low-quality apartment buildings have replaced much of the area’s historical fabric, erasing its constructed memory. The commune, spanning 1,550 hectares, has only 12 officially listed heritage buildings, reflecting the Chilean preservation policy’s focus on monumental heritage, often excluding smaller-scale or unrecognized historical structures.[13]

The Bypass San Pedro-Jama and Gas Atacama Pipeline infrastructure projects in Atacameño territory caused significant destruction to archaeological sites. The lack of consultation with indigenous communities led to disputes over the control and representation of archaeological heritage.[14]

Likewise, construction of the Bypass Temuco highway in Mapuche territory in 2015 disrupted burial sites, leading to protests by local communities. Although the human remains discovered were eventually returned to the Regional Museum of Araucanía, the project proceeded without adequately addressing Mapuche concerns, negatively impacting large areas and numerous communities.[15]

At about the same time, mining projects in Atacameño Territory have seriously impacted sites and community cultural preservation. Environmental impact projects, such as the one involving CODELCO, have led to contentious negotiations over the treatment of human remains and burial contexts. Indigenous leaders demanded minimal intervention and respect for cultural practices.

In San Pedro de Atacama, disputes arose over the management of archaeological sites like Tulor and Pukara de Quitor. While these sites were integrated into the Chilean government’s tourism initiatives, indigenous leaders are contesting their representation and control, demanding involvement in decisions regarding their ancestral heritage.

In Quillagua, an environmental project uncovered an archaeological burial site, sparking community efforts to preserve the remains and mitigate looting. Attempts at a collaborative process instead made clear the tensions between state and corporate interests and indigenous preservation goals.[16]

Neglect and Climate Change Threaten Many Heritage Sites

Archaeological Site of Monte Verde, the oldest known human settlement in the Americas

Monte Verde, located in southern Chile’s evergreen forests, dating from 13,000 to14,800 years ago, is the earliest known human settlement in the Americas. It was discovered in 1976, located in a peat bog about 500 miles south of Santiago. Excavations under layers of turf from a swamp have revealed timber-based rectangular dwellings with fur-lined walls, arranged in parallel rows, which likely housed a community of 20-30 people. A U-shaped structure with a compacted gravel and sand foundation appears to have been used for communal or ritualistic activities, including hunting, medicinal preparation, and possibly shamanic practices. Stone tools including projectiles, bolas, choppers, and digging sticks, and wooden tools like lances and mortars were also found. The inhabitants hunted mastodons, camelids, and small animals, but plant collection was central to their diet. Botanical remains included wild potatoes, seeds, berries, nuts, algae, and tubers, and this seasonal plant collection supported a year-round, sedentary lifestyle. Monte Verde challenges the traditional view of early humans as solely nomadic hunter-gatherers, showcasing evidence of a settled lifestyle, architectural innovation, and sophisticated ecological adaptation.[17] Today, however, there is nothing to see but a pretty green meadow. There is no public transportation available to the site, although tourists may engage private guides to take them there.

Chinchorro Culture Site- Endangerment of the World’s Oldest Mummies

The Chinchorro mummies, dating back 7,000 years, are the oldest known mummies in the world, predating Egyptian mummies by two millennia. The Chinchorro mummies are barely recognized compared to Egyptian mummies, partly due to limited international research and promotion. Local awareness in Chile is low, with many residents unaware of the mummies’ historical significance.

The Chinchorro people, a hunter-gatherer society, lived in coastal areas of modern-day northern Chile and southern Peru. The Chinchorro people developed intricate mummification methods, preserving bodies by using materials such as sand, clay, feathers, and plant fibers. They removed organs and muscles, reconstructed bodies, and even modified bone structures for aesthetic or preservation purposes. Unlike other ancient cultures, they mummified children and individuals with disabilities as well as full grown adults.

The San Miguel de Azapa Archaeological Museum is the chief holder of the Chinchorro mummies. Even with humidity control, the overall higher humidity in the Atacama Desert, attributed to climate change, has accelerated the decomposition of the mummies, with some turning into black ooze. Microbial activity on the mummies’ skin, triggered by the higher humidity, is breaking down the ancient remains. Many mummies remain buried in shallow graves, vulnerable to natural erosion, human development, and climate-induced changes. Arica, a modern city in northern Chile, is built above burial sites, and urban expansion further threatens them.

In 2021, UNESCO designated the Chinchorro mummies and their associated settlements as a World Heritage Site, highlighting the need for global efforts to preserve the mummies. Chilean researchers, including Marcela Sepulveda, have called for increased public and governmental support to raise awareness and implement long-term preservation strategies.[18]

UNESCO reports that despite these attempts to secure protection, there is increased illegal settlement in the proposed buffer zone and areas of burial, especially in Component 03, Desembocadura de Camarones. The installation of underground fiber optics has impacted the southern terrace of Component 03. Component 01, Faldeos del Morro, has experienced looting, animal disturbances, and improper solid waste disposal, all of which degrade the site’s condition. Open archaeological excavations in Component 03 require stabilization or backfilling to prevent further damage. Non-compliance with environmental regulations by nearby poultry farms in the Camarones River Valley has raised concerns about their impact on the site. Chile’s existing Law No. 17,288 on National Monuments lacks provisions for participatory processes, indigenous consultation, and Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA), which are necessary for comprehensive protection. While the Management Plan (2020-2026) has been approved, how integrated management and monitoring structures are to function has been left undefined.[19]

Frozen Inka Mummy

Some of the most sensitive and rarest archaeological finds are those of high-altitude mummies, sacrificial victims who may be found clothed in rich fabrics and jewelry. These human remains are not known to have been trafficked for decades, and even then were sold to museums in Chile. During the Inka Empire (1438–1533), children were ritually sacrificed in high-altitude ceremonies called capacocha, often as offerings to the gods during significant events like the death of a monarch. Physically perfect children were selected, paraded across the empire, and taken to sacred mountain sites where they were given coca leaves and maize beer to keep them calm. They were then killed by exposure, strangulation, or a blow to the head. Due to the extreme cold, their bodies were naturally mummified, preserving their soft tissues, clothing, and ritual artifacts.

In a looting that took place seventy years ago in 1954, treasure hunters led by Guillermo Chacón looted Inka ruins on Cerro El Plomo, a mountain in the Chilean Andes.[20] They discovered the frozen body of an Inka child at 4500 meters. They initially left the body in a cave, taking only the accompanying gold, silver, and ritual artifacts. Weeks later, they attempted to sell the objects in Santiago but faced challenges negotiating with museums. The head of the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural intervened, persuading the group to retrieve the El Plomo mummy and allowing them to purchase it. Today, the mummy is in the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural in Chile, but not on display. Similar mummies have been found in Peru and in Argentina, where the right of governments to possession to such remains is highly disputed by indigenous groups.[21]

Major Cultural Sites: Easter Island/Rapa Nui

Chile declared Rapa Nui a Chilean National Monument in 1935 and created a National Park there administered by the National Forest Service of Chile (CONAF). Since 1995 Rapa Nui National Park[22] has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site[23] covering 40% of the island of Rapa Nui. The park includes over 900 Moai, most of which have been placed back on the more than 300 ahu ceremonial platforms along the coastline in the traditional positioning – facing away from the water.[24] Others lie scattered in fields on hilly slopes, and along the island’s sea border. Many are half buried up to their shoulder, by tradition or because many standing moai had fallen or been pushed down by the 18th and 19th century. The statues stand 13 feet high on average; the largest, called Paro, was 33 feet tall and weighed over 90 tons

The park also includes the most visited site on the island, Orongo, the original home of Hoa Hakananai‘a and its fifty-three ceremonial structures dedicated to the Birdman tradition. By the time it was known outside of Easter Island, the moai tradition had faltered, in part as a result of European contact and the rise of another religious cult of Tangata Manu,[25] or Birdman. Recently, indigenous pride, recognition of the moai’s importance to the island’s history, and the rise of tourism, have resulted in many moai being raised again, including those originally placed on stone platforms called ahu. These characteristically face inland, away from the sea. Rock art sites, including petroglyphs and pictographs are also found there.

Cultural and Archaeological Significance

The Rapa Nui National Park was placed on the World Monuments Watch list in 1996 and again in 2000 due to concerns over lack of conservation and care for the site. Since 2001, extensive efforts have been made to develop Orongo and restore its ceremonial structures through funding by the World Monuments Fund and American Express.

A new visitor center, the Centro de Recepción de Visitantes de la Aldea Ceremonial de Orongo, was built in 2011. There is also a museum on Rapa Nui, the R. P. Sebastian Englert Museum of Anthropology,[26] which supports research and conservation efforts. The improvements to Orongo and the museum’s development of a cultural infrastructure to support its conservation have also prompted local interest in the repatriation of the British Museum’s Hoa Hakananai’a.[27]

Locals have repeatedly complained about tourism-driven archaeological exploitation in Easter Island, where foreign archaeologists have often excluded local labor and expertise from projects, creating distrust among the Rapa Nui people. The more recent incorporation of tourists into scientific expeditions has further strained relations, as it has reduced the local community’s historical ability to rely on archaeology for its livelihood.

The Rapa Nui community has also faced bureaucratic hurdles in reclaiming their ancestors’ remains, leading to conflicts over the state’s assertion of ownership versus the community’s genealogical claims. Chile’s Council of National Monuments has often regulated repatriation and reburial efforts, sidelining indigenous communities’ autonomy.

Rapa Nui was completely closed to tourists during the Covid pandemic. Two months after it reopened, on October 6, Rapa Nui authorities reported that a number of moai were severely damaged in a human-set fire that raced through 100 hectares (247 acres) of the Rapa Nui national park on October 6. According to Rapa Nui officials, a “lack of volunteers” caused delays in putting out the fire. By June 2023, UNESCO completed a detailed evaluation of the harm caused to the park’s archaeological treasures and emphasized the urgent need for immediate action to protect and preserve the globally significant heritage site.

The fires particularly affected the Rano Raraku area that served as the quarry for the famous moai statues. Many archaeological elements were exposed to extreme heat, compromising their preservation. Additional factors, such as erosion and biological impacts, have worsened the damage, leaving 22 moai in critical condition that requires urgent attention.

The damage observed includes discoloration, erosion, vegetation growth, lichens, and flaking. Among these, erosion caused by climate and water exposure was identified as the most significant issue, as it threatens the moai’s shapes and stylistic details. To address these challenges, specialists recommend controlling biological deterioration, applying materials to consolidate and protect the structures, and using water-repellent treatments. Additionally, long-term strategies such as fire prevention and mitigation efforts are vital to protect the area’s unique archaeological and cultural heritage.

The moai are highly protected under Chilean law – and by their importance to the island community. It is illegal to touch any of the nearly 1000 moai on the island. A Finnish tourist caused a “national uproar” and was fined $17,000 for chipping part of an earlobe off a moai[28] in 2008. In 2020, a Chilean resident on the island failed to properly brake his pickup truck, which rolled down a hill empty, striking and completely destroying a moai and its plinth at the bottom.[29] Many more moai have been lost to natural erosion of cliffs and damage from high seas and rough weather.

Serious Environmental Degradation and Lack of Resources

UNESCO has identified serious concerns over environmental degradation in Rapa Nui. Illegal cattle grazing damages vegetation and destabilizes archaeological structures. The proliferation of invasive plant species impacts the landscape and archaeological integrity. Weathering affects the volcanic tuff and other materials used in constructing moai and ahu.

Management and resource deficiencies include lack of infrastructure for visitor management, such as basic services and interpretation facilities, insufficient staffing and limited budgets for conservation, and lack of collaboration with the local community. Illegal land occupation is frequent and puts pressure on park lands from unauthorized settlements.

Indigenous Peoples and Archaeology

Archaeology in Chile has undergone an ethnographic shift that aims to address ethnic demands, mitigate the impact of research, and enrich archaeological interpretations by including indigenous perspectives. Several projects highlight this:

- In Ollagüe, Quechua territory, archaeologists renovated a local museum, and facilitated discussions among ethnic representatives, archaeologists, and state agents.

- Projects in areas like Belén and the Loa River basins employed “low-impact” methods, prioritizing indigenous consent and focusing on documentation and conservation.

However, conflicts remain. Indigenous communities, including Mapuche and Rapa Nui groups, have expressed dissatisfaction with archaeological practices that disregard their ancestral connections to heritage. These include concerns about excavation, the display of human remains, and the lack of informed consent. The history of archaeology in Chile reveals limited engagement with indigenous communities in regions like Arica and Parinacota and a history of neglecting informed consent and intellectual property.

Tourism remains the key reason for government interest in archaeology. Initiatives for the protection, and administration of archaeological sites, while designed for tourism, have increased. While these projects are primarily practical, some work to better align with indigenous priorities.

Overall, there is a growing acknowledgment of indigenous rights and perspectives in archaeological research, though challenges persist. For the most part, collaboration between archaeologists and indigenous communities has evolved through repeating stages of resistance, participation, and collaboration. Initial stages focused on indigenous resistance to outside interventions but recent efforts have included indigenous leaders and community members participation in various stages of archaeological projects, including surveys, excavations, and public education activities. In some cases, communities are actively involved in decision-making, ensuring research aligns with their cultural and ethical priorities.

Educational programs have been central to these efforts. The Andean School heritage program (2001–2010) in San Pedro de Atacama offered training in cultural management, tourism, archaeology, and indigenous legislation to Atacameño and Quechua communities. Similarly, heritage education initiatives with Mapuche Huilliches communities in southern Chile integrated oral history, material culture, and pedagogy in schools, museums, and archaeological field settings.

Despite greater focus on communication and collaboration, archaeological discourse dominates over indigenous narratives. Nonetheless, these programs aim to empower communities while promoting sustainable tourism and preserving Chile’s cultural heritage

Repatriation and Reburial of Indigenous Peoples

The Chilean state decides who is authorized and legitimated to reclaim excavated bodies and rebury them, as well as who is their rightful owner. The state regulates the procedures and determines which parties are authorized to make claims. Although Chile lacks a specific law on the matter, since 2009, the Council of National Monuments has provided guidelines for the reburial of remains at the request of communities.

The first repatriation occurred in the 1980s, prior to the Indigenous Law of 1993 and the U.S. NAGPRA Act of 1990. Atacameño communities requested the return of collections housed at the National Museum of Natural History. Subsequent cases involved Mapuche, Aymara, and Atacameño communities, often facilitated by agreements with institutions like the Smithsonian. Notable instances include the 2010 repatriation of Kawésqar remains from Switzerland and the 2011 return of mummies to the Miguel de Azapa Museum.

Collaborative projects, such as the Aymara community of Quillagua’s reburial ceremony and the Atacameño community of Taira’s negotiations with a mining company, illustrate efforts to balance indigenous rights with state regulations. However, some communities, frustrated by the lack of protection under patrimonial laws, have undertaken unauthorized reburials or opted for self-administration of discovered artifacts.

The Rapa Nui people have established their own independent repatriation program, emphasizing that their ancestors’ remains should be returned unconditionally to their community and challenging the state’s claim of national ownership.

Conclusion

Of all the issues discussed above, none are based on illicit trafficking of artifacts to the U.S. The Cultural Property Implementation Act is designed to deal with crisis situations of looting in which the sale of objects in the U.S. is the cause. The law requires proof that the U.S. is a primary market for looted artifacts taken today, not decades before.

Congress has also mandated CPAC to evaluate whether source countries like Chile are truly focused on halting archaeological looting and theft – securing and inventorying cultural sites, churches, and other vulnerable repositories of cultural items. Serious doubts remain whether Chile’s government is doing all that it can – or if its attitude to archaeology and site preservation basically indifferent. Chile has not sent an exhibition of its archaeological materials to the U.S. or supported and promoted its ancient and ethnographic art – except to bring in tourist dollars. Chile’s request for renewal fails to meet the statutory criteria required under the CPIA for imposing U.S. import restrictions. Specifically:

- No substantial evidence of a looting crisis.

- No proof of a significant U.S. market for illicit Chilean artifacts.

- Inadequate self-help measures to protect cultural heritage.

- Lack of any commitment to cultural exchange.

Instead of import restrictions, we urge additional funding for archaeological and ethnological projects in Chile by the U.S. government. Neglect and destruction of heritage in Chile is the direct result of underfunding and government disinterest. Past experience shows that public education and building pride in local heritage is the most successful way to combat the temptations to damage or neglect heritage.

In comparison to these proven benefits, U.S. border resources are being wasted by focusing on cultural property interdiction – hundreds of thousands of dollars are being spent to combat an illegal market that does not exist. This is the worst and most wasteful use of U.S. resources.

Thank you for your attention.

Committee for Cultural Policy, Inc.

[1] The Committee for Cultural Policy (CCP)[1] is an educational and policy research organization that supports the preservation and public appreciation of art of ancient and indigenous cultures. We deplore the destruction of archaeological sites and monuments and encourage policies enabling safe harbor in international museums for at-risk objects from countries in crisis. CCP supports policies that enable the lawful collection, exhibition, and global circulation of artworks and preserve artifacts and archaeological sites through funding for site protection. We defend uncensored academic research and urge funding for museum development around the world. We believe that communication through artistic exchange is beneficial for international understanding and that the protection and preservation of art from all cultures is the responsibility and duty of all humankind. The Committee for Cultural Policy, POB 4881, Santa Fe, NM 87502. www.culturalpropertynews.org, info@culturalpropertynews.org.

[2] The Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, 19 U.S.C. §§ 2601, et seq.

[3] U.S. Department of State, The Government of Chile’s Request for U.S. Import restrictions on Cultural Property, https://eca.state.gov/files/bureau/chile2018request_summary.pdf

[4] Id.

[5] In the last ten years, worldwide, Sotheby’s has sold several maps, a lithograph, two photographs, and a few watercolors and paintings by foreign visitors to Chile. https://www.sothebys.com/en/search?locale=en&query=chile&tab=objects&sortBy=bsp_dotcom_prod_en

[6] In recent years, contemporary art from Chile and by artists of Chilean heritage has been exhibited at New York University, the Denver Art Museum, and others, but these have been organized in the U.S. and Europe. The last truly major exhibit sponsored by the government of Chile was Chilean contemporary art, an exhibition sponsored by the Ministry of Education of the republic of Chile and the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Chile, which took place in 1941. https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/research/gallery-archives/PressReleases/1949-1940/1942/14A11_43556_19421010.pdf

[7] Santiago’s massive Metro de Santiago project has been the country’s most notable archaeological project. 13,000 year old remains found in Santiago’s subway construction site, Sharjah 24 News, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-IR9cGN6h8E

[8] From arrows to the remains of the Mapocho breakwaters, the more than 180 thousand archaeological pieces found under the Metro. https://www.latercera.com/que-pasa/noticia/de-flechas-a-restos-de-los-tajamares-del-mapocho-las-mas-de-180-mil-piezas-arqueologicas-encontradas-bajo-el-metro/RE7CZ3EKRVB2ZEBG4FMFOBZ4YY/

[9] Off-Road Racing Destroys Chilean Geoglyphs While AI Enables Hundreds of New Finds in Peru, Cultural Property News, October 15, 2024, https://culturalpropertynews.org/off-road-racing-destroys-chilean-geoglyphs-while-ai-enables-hundreds-of-new-finds-in-peru/.

[10] Id.

[11] Patricia Ayala, Archaeology and Indigenous Communities of Chile, 2019, Chilean Archaeological Society, Santiago, Chile, https://www.academia.edu/37867155/Chile_Archaeology_and_Indigenous_Communities_of,

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] New evidence from earliest known human settlement in the Americas supports coastal migration theory, May 8,2008, https://news.vanderbilt.edu/2008/05/08/new-evidence-from-earliest-known-human-settlement-in-the-americas-supports-coastal-migration-theory-58122, and Pino, Mario; Dillehay, Tom D. (June 2023). “Monte Verde II: an assessment of new radiocarbon dates and their sedimentological context”. Antiquity. 97 (393): 524–540.

[18] Paul Karoff, Saving Chilean mummies from Climate Change, Harvard News, March 9, 2015, https://seas.harvard.edu/news/2015/03/saving-chilean-mummies-climate-change

[19] UNESCO, Settlement and Artificial Mummification of the Chinchorro Culture in the Arica and Parinacota Region, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1634/, and Can UNESCO status save the world’s oldest mummies?, October 25, 2021, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/can-unesco-status-save-the-worlds-oldest-mummies.

[20] Plomo Mummy, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plomo_Mummy

[21] Juan Javier Negri, The Llullaillaco Mummies, Cultural Property News, October 20, 2022, https://culturalpropertynews.org/the-llullaillaco-mummies/

[22] World Monuments Fund, Easter Island (Rapa-Nui) Orongo, https://www.wmf.org/projects/easter-island-rapa-nui-orongo.

[23] UNESCO, Rapa Nui National Park, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/715.

[24] Easter Island, New World Encyclopedia, http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Easter_Island.

[25] The Birdman Motif, Therianthropic Figure, Half Man & Half Bird, The Rock Art of Easter Island, Bradshaw Foundation, https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/easter/birdman/index.php

[26] MAPSE Museo Rapa Nui, https://www.museorapanui.gob.cl/.

[27] Hoa Hakananai’a, British Museum Collection, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/E_Oc1869-1005-1

[28] Easter Island tourist faces fine, 3-year ban, NBC News, April 7, 2008, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna23981856

[29] Christine Hauser and Alan Yuhas, Truck Crashes Into an Easter Island Statue, March 6, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/06/world/americas/easter-island-statue.html

Mataveri Airport, Easter Island, By Jialiang Gao www.peace-on-earth.org, via Wikimedia Commons.

Mataveri Airport, Easter Island, By Jialiang Gao www.peace-on-earth.org, via Wikimedia Commons.