Peace Corps ID card, Nigeria 1965, photo Rcollman, public domain.

Doug joined the Peace Corps in his twenties straight out of the University of Chicago. He was posted to Nigeria from 1992-1995 when the Peace Corps mission there ended. Doug came from a wealthy family and had a minor in Art History. As a result, he had both the interest and financial means to purchase some art while he was posted in what was formerly the Kingdom of Benin. After leaving the Peace Corps, Doug attended and graduated from Yale law school, and then secured a position with a prestigious Washington, DC firm.

A few years later, he married another lawyer who worked with the federal government whom he had first met during his time with the Peace Corps. They had twins, a girl and a boy, who are now enrolled in a well-known “feeder school” for the Ivy League.

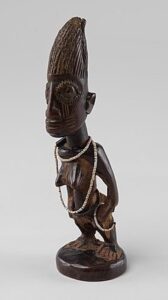

Ere ibeji, memorial figure for a twin, Nigeria, 19-20th C, Brücke Museum, Photo Nick Ash, 8 June 2021.

While Doug’s collecting has slowed due to the expenses associated with his kids’ pricey private school, he has still added some additional pieces to his collection purchased from long established ethnographic art dealers. He particularly likes metal work from the former Kingdom of Benin in today’s Nigeria, the same area where he was stationed while in the Peace Corps.

As a lawyer with an interest in African art, Doug has followed what began as an academic debate, but which has become a rush to repatriate artifacts voluntarily from Western museums, especially so-called “Benin bronzes” that were looted during a punitive raid by British troops in 1897. Little did he realize, however, that this debate would come home as the result of an assignment the twins received from their history teacher. The twins’ history teacher tasked their class to write an essay about repatriating art to Africa. From discussing the assignment, Doug surmised that the teacher had conveyed little more than the narrative that all African is “stolen” and must be returned.

After wondering for a moment whether all that tuition money was really well spent, Doug discussed the matter with his sympathetic wife, and they both agreed he should use the assignment as his own “teaching moment” for the kids. Doug’s hope was that the twins would at least learn that historical rights and wrongs are often not as clear as usually portrayed.

Doug took the twins back to his study where his African art was displayed to discuss the issue. The twins had grown up with the collection, but had taken only minimal interest over the years, other than commenting that some of the pieces “looked creepy” and might make good decorations for Halloween. Now, Doug wondered if this “teaching moment” would make his collection more meaningful to them or if the talk would just help solidify their teacher’s view that all African art should be treated as “stolen.”

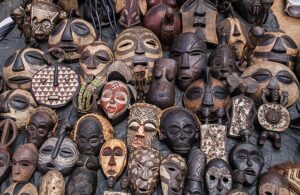

Fred van der Kraaij, A table on the market showing African pseudo old artifacts. Statues (Bambara, Dogon, Senoufo, and Lobi), straw Mossi baskets, small brass statues and figurines, bone carvings, and brass bracelets. Niamey, Niger, 1972, CCA-SA 4.0.

Doug began by discussing his own service in the Peace Corps and how he purchased his first pieces from local artisans who were happy to sell them so they could provide for their families. He then discussed his other purchases from established ethnographic dealers. He told the kids one could not assume all African art is stolen. Instead, many of the artifacts of an animistic religious nature on the market today were sold by Africans themselves after they adopted Christianity or Islam. Much more was simply destroyed as idolatrous. Doug added that nothing in his collection is known to have been looted during the 1897 punitive raid, and that African art owners and their property should be treated as “innocent until proven guilty,” which is a bedrock principle of our American legal system.

Doug then gave his “history is not black and white” lesson. He first acknowledged that Colonialism has damaged societies in Africa and elsewhere but argued that context remains important. For example, the United Kingdom, despite its colonialist past, was a growing Democracy in the 19th century where public opinion forced positive changes. Indeed, such public opinion made the UK one of the first countries to not only abolish slavery, but to actively fight against it. In contrast, the Kings of Benin grew rich through slavery, and it was the wealth derived from the slave trade that helped pay for the metal sculptures the British looted. Indeed, the so-called “Benin bronzes” were actually cast from brass “manillas,” a type of currency in bracelet form that was used to buy and sell slaves in West Africa. Calling them “bronzes” rather than brass sculptures was a form of compliment, associating them with bronze sculptures which had been collected by wealthy Europeans since at least the 15th century.

Brass weight for measuring gold, Africa, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, Photo Roger Culos, 23 October 2014, Museum Toulouse, former collection of French botanist Jean Baur, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Nor was the 1897 punitive expedition without cause. In fact, the British were responding to the massacre of a British trade delegation. Finally, while the destruction in the raid caused protests in the UK even at the time, looting was a commonplace practice for victorious armies. Today, looting cultural heritage is considered a war crime, but it still persists to this day, most recently in Ukraine where Russian troops have despoiled Ukrainian museums.

Doug continued to say that there are other issues that should be considered. First, the dispersion of art both protects it and exposes it to many more people than if it were to all be repatriated to where it was produced hundreds, if not thousands, of years ago. Second, by having such art here in the US, African Americans, both the descendants of former slaves as well as more recent immigrants, can enjoy and learn from it about their own heritage. Indeed, an advocacy group representing the interests of descendants of those enslaved by the Kingdom of Benin are fighting to have Benin bronzes stay here in the United States so their whole story can be preserved for posterity.

African masks in market, Nairobi, Photo by Ninaras, 2 May 2015, CCA 4.0 International license.

After the twins listened to Doug, they told him what he said made them want to learn more about the subject. In a hopeful sign they also asked for some additional reading materials, information Doug was happy to provide. Now, Doug anxiously awaits their essays, wondering how much he told them sunk in, and if they will hold onto his African art as a memory of him or repatriate it once he is no longer around to enjoy it.

Next Month: The Life Cycle of Collectibles

‘Manilla’ copper alloy bracelet with flared terminals, used as currency in West Africa slave trade. West Yorkshire Archaeology Advisory Service, Amy Downes, 2011-07-12. Courtesy The Portable Antiquities Scheme/ The Trustees of the British Museum, CCA-SA 2.0 Generic license.

Further Reading:

On repatriation:

Adenike Cosgrove, Send It Back! Chronicling the African Art Repatriation Debate, Imo Dara (Oct. 16, 2022), available at https://www.imodara.com/magazine/send-it-back/ (last visited November 23, 2022).

Kate Fitz Gibbon, Where will Benin bronzes go? Nigerian government, Edo Museum or Oba? Cultural Property News (October 4, 2022), available at https://culturalpropertynews.org/where-will-benin-bronzes-go-nigerian-government-edo-museum-or-oba/ (last visited November 23, 2022).

David Frum, Who Benefits When Western Museums Return Looted Art? Atlantic Magazine (October 2022), available at https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/10/benin-bronzes-nigeria-return-stolen-art/671245/ (last visited November 23, 2022).

On looting in wartime today:

Committee for Cultural Policy Staff, Putin Using Martial Law to Legitimate Ukraine Art Looting, Cultural Property News (October 30, 2022), available at https://culturalpropertynews.org/putin-using-martial-law-to-legitimate-ukraine-art-looting/ (last visited November 23, 2022).

On Manilla currency:

Shailendra Bhandare, A Brass Manilla, Ashmolean Museum (Undated), available at https://www.ashmolean.org/article/brass-manilla-west-africa#:~:text=Although%20used%20primarily%20for%20exchange,West%20Africa%20to%20procure%20slaves.(last visited November 23, 2022).

[1] Peter K. Tompa has written extensively about cultural heritage issues, particularly those of interest to the numismatic trade. Peter contributed to Who Owns the Past?” (K. Fitz Gibbon, ed, Rutgers 2005). He currently serves as executive director of the Global Heritage Alliance. (https://global-heritage.org/) This article is a public resource for general information and opinion about cultural property issues and is not intended to be a source for legal advice. Any factual patterns discussed may or may not be inspired by real people and events.

Hand-carved art on exposition on a street market in Angola, Photo by Paulo César Santos, July 2009, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Hand-carved art on exposition on a street market in Angola, Photo by Paulo César Santos, July 2009, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.