Monuments Men Lt. Frank P. Albright, Capt. Everett Parker Lesley, Polish Liaison Officer Maj. Karol Estreicher, and Pfc. Joe D. Espinosa, pose with Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine upon its return to Poland in April 1946. U.S. federal government, public domain.

In March 1945, U.S. troops crossed the Rhine River at Remagen and began their final push to defeat Nazism and end the Second World War. During their march through Germany, members of that victorious army “liberated” countless “souvenirs” of all sorts, mailing them back home. Now, as the WWII generation fades away into history, some of those “souvenirs” are being recognized as significant cultural artifacts and are being repatriated to Germany, long since a vibrant Democracy, as part of its patrimony.

Unlike Stalin’s Red Army which created specialized “trophy brigades” to systematically plunder enemy territory, the U.S. military adhered to international law which distinguishes between “spoils of war” taken from combatants on the battlefield and pillage of civilian possessions. Indeed, after receiving complaints about looting in France and Belgium, General Eisenhower’s Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) issued special orders meant to protect Germany’s defeated population from any depredations of a victorious American army. The problem was that while such orders were dutifully conveyed down the chain of command, junior officers typically overlooked transgressions during the bitter fighting that took place in 1945. As one tanker recalled his commanding officer to say,

German loot stored at Schlosskirche Ellingen, Bavaria, Germany found by troops of the U.S. Third Army, Office of the Chief Signal Officer, U.S. federal government, public domain.

The Colonel reminds us all there is to be no looting. Seems like some people have complained about things being taken from their homes. The rule is no looting! Then, half under his breath, “If you do any, see that you don’t get caught.”[2]

There certainly were plenty of opportunities given U.S. military doctrine that placed well-armed troops in close proximity with German citizens and their possessions. In 1945, it was standard U.S. military procedure for all houses in occupied territory to be searched for weapons that might be used by Nazi “Werewolf” units for an insurgency. Moreover, given Germany’s cold, rainy weather and the desire to control its conquered population, soldiers were quartered in homes upstairs while their owners were confined to basements. With so many well-armed troops in a position of power over a defeated enemy blamed for starting a total war that killed millions and precipitated the intentional destruction and looting of cultural treasures of the nations under Nazi rule, it is no big surprise that most GIs felt little remorse about taking a few “keepsakes” of their occupation of Germany.

Master Sergeant Harold Maus of Scranton, PA is pictured with a Durer engraving, found at Merker, 13 May 1945, National Archives at College Park – Archives II (College Park, MD).

Alcohol, watches and expensive Leica cameras were favorite “souvenirs,” but sometimes far more significant cultural artifacts, such as paintings, old master drawings, statuary, silver plate, historic coins, medals, and jewelry were also taken as trophies. Souvenir hunting GIs felt that they really hit the jackpot when they prospected the homes of Nazi functionaries or the ruins of bombed out cultural institutions, especially museums. Less frequently, cultural treasures were pilfered from heavily fortified concrete flak towers and bunkers or underground caves and mines that had been used as protection from allied bombing. The U.S. had formed a special unit of “Monuments Men” to take custody of such cultural treasures for safekeeping, but they were rarely the first on the scene, giving sticky-fingered GIs at least some time to score a few choice items. These were then either mailed back home or traded with other soldiers for Lugar pistols, SS ceremonial daggers, Nazi battle flags, cigarettes, liquor or whatever else that might be available and in demand.

Rembrandt self-portrait in the salt mine of Heilbronn is inspected by Lt. Dale V. Ford and Tec 4 Harry L. Ettlinger. Heilbronn, Germany, 3 May, 1946, photo by PFC Louis Meyer, US Army Signal Corps Photographer, U.S. federal government, public domain.

When WWII veterans began passing away in substantial numbers in the 1980’s, these cultural treasures started coming to light when heirs sought to sell them on the open market. Relatives sometimes received a “finder’s fee” for returning such items to German government institutions, but other times they donated these items voluntarily or only gave them up unwillingly after some “encouragement” to do so by U.S. law enforcement.

Perhaps the most famous return is the Quendilnburg Treasure, a trove of Medieval relics from the City’s cathedral, including objects associated with Henry I who is considered to be Germany’s first king. During the Third Reich, this association with Henry helped turn both Quendilnburg’s castle and cathedral, located in the Hartz mountains, into a Nazi shrine. The cathedral’s medieval treasure was removed at the end of WW II from a cave by a U.S. Army First Lieutenant, and then mailed back to his hometown in Texas. After he passed away in 1980, his heirs tried to sell the trove, but ended up settling for a $912,500 finder’s fee to facilitate the return of the items to Germany.

Francisco de Goya, Time and the Old Women, recovered by U.S. military, photo circa 1945, U.S. federal government, public domain.

Other recent returns include paintings, a Roman portrait bust from the Julio-Claudian period, a Flemish tapestry taken from Hitler’s “Eagle’s Nest” by a Lt. Colonel assigned to the 101st Airborne Division, a cane once owned by “Mad” King Ludwig II of Bavaria, some coins, and a wooden sculpture depicting Albrecht Ludwig Berblinger, the “Flying Tailor from Ulm”.

While the provenance of some of these items is uncertain, others have been repatriated with a showing of remorse for what was done so many years ago. The story of the return of some historic coins of modest value is a poignant one. According to the Monuments Men and Women website,

As to the coins, the Foundation received an anonymous package containing a note, the copy of a letter and a smaller parcel. The package contained nine coins. The note stated:

“Gentleman: The enclosed package contains some damaged coins that were looted from an exhibit at, I was told, Ulm, Germany, during at [sic] assault on the city by U.S. forces in 1945, during World War II. An explanatory note is enclosed with the coins. After you have inspected the package, would you please forward it to Ulm? Thank you.”

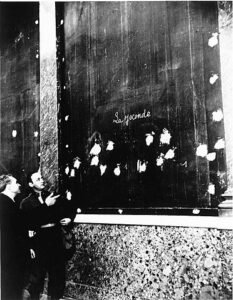

Monuments Man James Rorimer (right) and Ecole du Louvre director Robert Rey, stand before the empty wall where the Mona Lisa (La Joconde) hung before its precautionary evacuation from the Louvre in 1939. Paris, September 12, 1944, credit: National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, public domain

The letter, signed “A former American soldier,” was addressed to the Mayor of Ulm and explained that the coins were given to the writer by a fellow American solider, who had come across a display case containing the coins in a town museum, had impulsively smashed the glass of the case with his rifle butt, scooped up the coins, and taken them with him as his unit moved on. After hostilities had ended, he decided he no longer wanted the coins and had given them to the writer, who then modified them to be worn as pendants. He apologized for the damage caused to the coins, and wished them to be returned to the town of Ulm.

(Sculpture of Albrecht Berblinger, the “Flying Tailor from Ulm” and Nine Coins, Monuments Men and Women Foundation.)

With remaining WWII veterans now at least in their 90’s, the Monuments Men and Women Foundation hopes to help facilitate such returns. Indeed, its website contains useful information for heirs who ponder what to do with these last “souvenirs” of the bloody dénouement of the Third Reich.

Meanwhile, Putin’s Russia still holds many items pilfered by Red Army soldiers or taken by Stalin’s “trophy brigades,” the most significant of which must be the famous Schliemann treasure looted from a Flak Tower in Berlin at the end of WWII. It’s unlikely that such objects will be returned anytime soon, barring a major change in the Russian Government and its public’s attitudes about Stalin and the “Great Patriotic War.”

Next Installment: Importing Antiquities, Art and Collectibles into the EU Becoming Far More Challenging

Further Reading

Paintings in Klesshiem Palace or Castle, including Pieter Bruegels’ The Peasant Wedding. Behind the paintings is a corporal of the US Forces.

Articles:

Sarah Kuta, Painting Stolen by U.S. Soldier During WWII Returned to Germany, Smithsonian Institution Smart News (October 25, 2023).

Sarah Cascone, After 80 Years, a Long-Lost Painting Looted by U.S. Soldiers During World War II Has Been Returned to Germany, Artnet (October 20, 2023).

Frank Thadeusz, A New Look at the Great Quedlinburg Art Robbery, Spiegel International (May 26, 2023).

World War II Cultural Property Cases, Fact Sheet, U.S. Immigration and Customs Service (April 14, 2023).

Yekaterina Ivanova, How the Gold of Troy Became the USSR’s War Booty, Russia Beyond (April 5, 2023).

Elizabeth Dijinis, Ancient Roman Sculpture Likely Looted During WWII Turns Up at Texas Goodwill, SmartNews, Smithsonian Magazine (May 6, 2022).

Tom Mashberg, Returning the Spoils of World War II, Taken by Americans, The New York Times (May 5, 2015).

David Malakov, American Soldiers Saved Great Art. They Also Stole Some, Slate (Feb. 7, 2014).

Seth A. Givens, Liberating the Germans: The US Army and Looting in Germany during the Second World War, War in History , January 2014, Vol. 21, No. 1 (January 2014), 33-54.

Pastoral painting taken by an American soldier. Vienna-born artist Johann Franz Nepomuk Lauterer, 1700-1733, Landscape of Italian Character. Photo Art Recovery International.

Website:

Monuments Men and Women Foundation

Notes:

[1] Peter K. Tompa is a semi-retired lawyer who resides in Washington, D.C. He has written extensively about cultural heritage issues, particularly those of interest to the numismatic trade. Peter contributed to Who Owns the Past?” (K. Fitz Gibbon, ed. Rutgers 2005). He formerly served as Executive Director of the Global Heritage Alliance and now is a member of its Board of Directors. He currently serves as the Executive Director of the International Association of Professional Numismatists. This article is a public resource for general information and opinion about cultural property issues and is not intended to be a source for legal advice. Any factual patterns discussed may or may not be inspired by real people and events. The opinions stated in this article are the author’s alone and should not be attributed to any affiliated organization.

[2] John P. Irwin, Another River, Another Town: A Teenage Tank Gunner Comes of Age in Combat, 1945, 83 (Random House, New York 1983), quoted in Seth A. Givens, Liberating the Germans: The US Army and Looting in Germany during the Second World War, War in History , January 2014, Vol. 21, No. 1 (January 2014), at 51, available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/26098365 (last visited June 15, 2024).

Pfc. Ivan Babcock, of the 165th Signal Photo Company, 1st US Army, tries on the gold and pearl crown of the Kaisers of Germany, in an underground cave at Siegen, Germany. 3 April, 1945.

Pfc. Ivan Babcock, of the 165th Signal Photo Company, 1st US Army, tries on the gold and pearl crown of the Kaisers of Germany, in an underground cave at Siegen, Germany. 3 April, 1945.