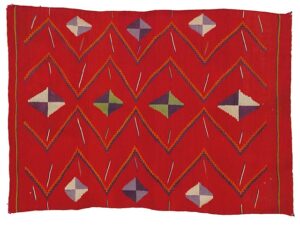

Navajo Transitional Period weaving, Saint Louis Art Museum: “Navajo Weavings from the Andy Williams Collection,” October 26, 1997 – January 4, 1998

Robert “Bob” Gallegos has interacted with Native Americans from the Southwest for decades as a dealer in tribal arts, an auctioneer, and as former President of ATADA, the Authentic Tribal Arts Dealer Association. Some years back, Bob had an epiphany after the federal government started using its police powers to return artifacts to the tribes in the American Southwest. Often, the returns only happened under pressure after a heavy-handed criminal investigation predicated on the assumption that the items were “stolen.” Sure, the tribes “won” the return of their sacred artifacts, but only after an acrimonious battle in the courts and in the press. Bob saw that all the negative publicity only helped poison mutually beneficial relationships between the tribes and dealers and collectors. After all, it takes collectors and dealers to support Native American crafts and all the cultural and economic benefits they have brought to community members. Bob thought there had to be a better way, and so the idea of the ATADA Voluntary Returns Program was born in 2016.

Window Rock, Arizona. Diné bizaad: Tségháhoodzání, Hoozdoh Hahoodzo. Photo by Ben FrantzDale, 19 August 2006. CCA-SA 3.0 license.

From the beginning, the program has been based on mutual understanding, trust and good faith. Efforts at mutual understanding are necessary to bridge gaps in perceptions found in dealer/collector and Native American communities. These gaps relate principally to evidence showing that a sacred item is stolen or even whether it should be considered sacred at all. These controversies helped feed media coverage and have been the source of much of the acrimony.

Collectors observe that many sacred artifacts were originally released onto the market decades ago after the tribes adopted Christianity and turned away from their ancestral religion. They note that Native American craftsmen have made artifacts indistinguishable from sacred ones to outsiders. These replicas can be found for sale at markets in Santa Fe and elsewhere. Moreover, collectors have pointed to a lack of police reports to show that items were actually stolen. In their view, one cannot assume that such items are stolen or even sacred at all.

Navajo Eyedazzler weaving, Exhibited Saint Louis Art Museum: “Navajo Weavings from the Andy Williams Collection,” October 26, 1997 – January 4, 1998

In contrast, Native American advocates for returns have countered that sacred items were always held as community property and could not be sold legally by individual tribal members. Some have also taken the position that only items signed by native artists can be held by outsiders legally as examples of Native American crafts. Collectors respond by noting that the practice of native artists signing their work is a recent one, driven by collector demand, not a desire to verify that an object is not sacred.

Cutting through these perceptions, Gallegos has relied on trust and good faith to foster mutual understanding and voluntary returns of sacred artifacts. Bob has trusted the tribes to only lay claim to objects that are truly sacred. Bob has come to trust the determinations of tribal religious figures as to which items are sacred because he knows they believe that violating that trust would have deleterious spiritual consequences. He also knows that collectors and dealers have come to trust a voluntary system of return through ATADA because their privacy is respected.

View from Hopi Point over Grand Canyon with rainbow. Photo by Txyso, 8 September 2013, Tuxyso / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0.

In conjunction with the creation of its voluntary returns program, ATADA has modified its bylaws to prohibit members from selling sacred items that currently have ceremonial use. ATADA has also adopted due diligence guidelines directed at prohibiting sales of items removed unlawfully from tribal communities. Finally, ATADA has created educational programs for the public aimed at raising awareness of the issues. Gallegos has also consulted with other dealers and auction houses, including Heritage, Bonhams and Cowan’s, regarding what items should be considered sacred and subject to possible return.

The results have been impressive. So far, ATADA has returned well over four hundred artifacts with Gallegos often driving long distance to facilitate the returns himself. Items that have been returned include an Apache Crown (Gan) Headdress used in the Apache Crown dance ceremony, a Zuni war god, Acoma and Laguna flat and cylinder dolls, Hopi ‘friends’ dolls, Navajo Yei masks, prayer sticks, bandoliers, rattles, arrowheads, altars and altar elements, and other items from shrines belonging to a particular Native community.

Southwest, Pueblo (Hopi or Rio Grande), Post-Contact, Early Period, Ceremonial Dance Kilt, Cleveland Museum of Art, between circa 1900 and circa 1925, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

The tribes view these returns as a way to promote healing of past wrongs. Gallegos has received letters of appreciation from tribes, including the Navajo, prompted by the return of traditional Navajo Jish, or medicine bundles to the tribe.

Of course, success encourages emulation. Recently, the federal government announced plans to establish its own voluntary returns program as part of a statutory scheme to ban exports of Native American grave goods and sacred objects. It remains to be seen if a program involving federal authorities is as successful as this initiative based on mutual understanding, trust, good faith as well as the protection of collector privacy.

Note: No sacred items have been illustrated with this article, only holy places.

Next Installment: Resetting the Collecting Narrative

Further Reading:

ATADA Voluntary Returns Program, available at https://atada.org/voluntary-returns (last visited July 20, 2023).

CCP Staff, Art Dealer Program Brings Over 100 Artifacts Back to Tribes, Cultural Property News (March 12, 2018).

James Compton, Repatriating a Zuni War God Plank, James Compton Historic Native American Art (May 16, 2020)

[1] Peter K. Tompa is a semi-retired lawyer who resides in Washington, D.C. He has written extensively about cultural heritage issues, particularly those of interest to the numismatic trade. Peter contributed to Who Owns the Past?” (K. Fitz Gibbon, ed. Rutgers 2005). He formerly served as executive director of the Global Heritage Alliance and now is a member of its board of directors. (https://global-heritage.org/) This article is a public resource for general information and opinion about cultural property issues and is not intended to be a source for legal advice. Any factual patterns discussed may or may not be inspired by real people and events.

Hopi Point, Grand Canyon (South Rim), Arizona, USA, photo by Alan D. Wilson, 26 January 2017, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

Hopi Point, Grand Canyon (South Rim), Arizona, USA, photo by Alan D. Wilson, 26 January 2017, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.