Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo is Restored for Tourism

A restoration project undertaken in 2022 by the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities culminated in a grand opening with Egyptian dignitaries at the end of August 2023. There were no Jews in attendance for the opening.

Egyptian Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly (center) attends the inauguration of the newly restored Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo, Egypt, August 31, 2023. Egyptian Cabinet photo.

The Ben Ezra Synagogue is located in Fustat, in Old Cairo. Originally founded in the 9th century CE, it is considered the oldest synagogue in Cairo. The current building dates mostly to the 1890s; the synagogue has been partially destroyed and rebuilt several times over the centuries. The synagogue has been restored more than once and has served as a tourist destination in Cairo for years. Visits are expected to increase after the current rehabilitation of the synagogue.

Since the number of Jews remaining in Egypt can now be counted on one hand, the Sisi government’s focus is exclusively on promoting foreign tourism, not on restoring cultural ties with the Egyptian Jewish diaspora. Cairo’s Jewish population numbered almost 50,000 before the 1956 and 1967 wars. The forced emigration of the vast majority of Egyptian Jews in the mid-20th century left the Ben Ezra synagogue deserted and dilapidated for decades.

The newly restored Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo, Egypt, August 31, 2023. Egyptian Cabinet photo.

For its re-opening as a tourist site, the synagogue has been cleaned, its ceiling repaired and its lighting and wall decoration restored. The synagogue is not intended for worship, but to be seen as a relic of Jewish history in Egypt.

Tourist travel to Egypt underwent a significant drop in popularity after turbulence of the Arab Spring and the violent crackdowns that followed. It has still not recovered, but rather than learning from the travel industry’s dictum that “democracy promotes tourism,” the Egyptian government appears to hope that building museums and promoting new venues will distract the world from its authoritarian rule. Notwithstanding Egypt’s appalling human and civil rights abuses against political dissenters and multi-year prison sentences given to TikTok-ing teenage girls for “violating family values,” Egypt’s government has made conciliating gestures in some areas of culture. One is to encourage cooperation between Egyptian authorities and foreign Jewish heritage organizations dedicated to restoring ancient sites and cemeteries.

Ben Ezra Synagogue in Old Cairo, founded in 882 CE and site of the Cairo Genizah.

Egypt’s on-again off-again support for restoration of Jewish heritage in Cairo demonstrates both its government’s interest in promoting Jewish tourism to Egypt and its marked reluctance to commit to a more significant commitment to allow researchers and scholars access to the Jewish community’s historical records.

In the last decade, a number of Jewish sites have been refurbished and restored – with the approval of the Egyptian government but with much of the funding coming from the USA. The Egyptian government not only cooperated in the restoration but also provided much of the funding for cleaning and restoring the Eliyahu Hanavi synagogue in Alexandria and most recently, the Ben Ezra synagogue in Cairo.

The newly restored Ben Ezra is known worldwide as the original holding place of the Cairo Geniza, discovered in an attic in the women’s section, the most private in the synagogue, in 1896. The term Geniza designates a repository of discarded writings. According to medieval Jewish tradition, no writing that contains the name of God should be destroyed by fire or otherwise; it should instead be put aside in a special room for perpetuity or buried in a cemetery.

Solomon Schechter studying the fragments of the Cairo Genizah, c. 1898. Public Domain.

While the existence of a Geniza in the temple was known to European travelers by the late 18th century, its extent and importance was not realized. In 1895, the scholar Solomon Schechter of Cambridge was shown some fragments from the Geniza and immediately recognized their significance. Schechter and fellow scholar Charles Taylor organized an expedition to Egypt in 1896-1897, where they worked with the Chief Rabbi to sort and remove over 400,000 documents and fragments of texts dating from the 6th to the 19th century. Now dispersed to some seventy university and museum collections in Britain, Europe and the United States, the records of the Cairo Geniza are in process of full digitization, and tens of thousands are already available to students, scholars and the public online.

The texts in the Ben Ezra synagogue Geniza are arguably one of the most valuable resources for the study of the medieval Mediterranean world. While many Geniza documents are religious texts and commentaries, Geniza archives can be incredibly varied. They are an immediate, direct window into the past, sometimes stretching back more than a thousand years. They contain not only the records of politics and the actions of rulers as experienced by Jewish communities but also highly personal documents. Geniza records have been essential to our understanding of routes and patterns of trade and international rates of exchange in the medieval world, but they also contain an extraordinary variety of documents illuminating the lives of ordinary people. The details they contain have enabled researchers learn about family, business, and community relationships that can be seen through thousands of personal communications such as marriage and divorce records, letters sent home by distant traders and records of the negotiation of property and business contracts.

The refurbishment of two synagogues is a welcome move – but one tinged with bitterness when looking to the decades of past vandalism and deliberate destruction of Jewish cemeteries and places of worship. The importance of the known Geniza records to scholarship in the last 100 years also points to the depth of loss of another potential treasure trove of information when Egyptian authorities seized a newly discovered Geniza from a Jewish cemetery in 2022 – a treasure whose whereabouts remains unknown.

Building a Record of Egypt’s Jewish Past from Garbage Dumps

Inside of the Synagogue of Moses Maimonides before its renovation in 2010, Jewish quarter, el-Muski, Cairo, Egypt, Photo Roland Unger, 27 February 2006. CCby SA 3.0 license.

The story of the lost Geniza begins with how decades of neglect of Jewish synagogues and cemeteries in Egypt inspired foreign activists and historians to extraordinary efforts to retrieve and preserve what remains. Prof. Yoram Meital of Ben-Gurion University’s Middle East Studies Department has been active in helping Cairo’s Jewish community to restore cemeteries and places of worship. He has expressed appreciation for the Egyptian government’s support of restoration and cleanup of Jewish sites, saying that the government’s attitude has much improved under the Sisi regime. He told Israel’s Haaretz News Magazine that, “conserving Jewish heritage as part of Egypt’s heritage depends on the wide support of Egypt’s government and society.”

The position of the Jewish heritage workers volunteering in preservation projects in Egypt today is that in principle, Jewish items should remain in Egypt. The Egyptian government has remained rigidly tied to this position, and even Torahs are listed in an Egyptian agreement executed by the U.S. State Department that blocks imports of objects taken from Egypt and requires returning them to its government. Jewish and Christian ritual objects, including antique Torah scrolls, tombstones, books, Bibles and religious writings are covered under these agreements.

(See Egypt’s Brutal Regime Wants to Renew US Blockade on Art; Claims to Protect Heritage & Culture, CPN, March 10, 2021)

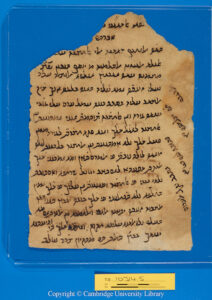

Letter (T-S 10J14.5) Recommendation by Moses Maimonides to a judge in a provincial town. 1235 CE, Donated by Dr Solomon Schechter and his patron Dr Charles Taylor in 1898 as part of the Taylor-Schechter Genizah Collection. © Cambridge University Library.

Meital has also said that the volunteers understand that restored synagogues could be used as public community centers, “on condition that they don’t change anything having to do with artifacts and architecture.” This perspective is controversial among Egyptian Jews in the diaspora, for whom Jewish religious objects should belong to Jewish communities and a synagogue is exclusively a place for worship and study.

Without the efforts of the Jewish volunteers and that of Egyptian supporters who share concerns for preservation, almost all Jewish religious heritage, whether synagogues or cemeteries, would be at risk of destruction through neglect or appropriation. Meital says that he and others working to restore synagogues have recovered over 1000 books from disused buildings, “strewn all over the place.” They also found a metal container in the cellar of a Cairo synagogue filled with records of the entire Ashkenazie community in Egypt. Their most important find was in a Karaite synagogue in Cairo, a manuscript of the Bible written 1,000 years ago. The project hopes to establish a library in Cairo to hold all the materials they have collected and are now documenting, but for now, the finds are being held in a “safe location.”

Meital’s main focus has been to photograph and document in detail the existing conditions, any inscriptions, architectural forms, or remaining ceremonial objects in old Jewish sites in Egypt for a comprehensive database. Meital says that there are 16 known synagogue buildings in Egypt – 13 of these are in Cairo. A number of cemeteries were deemed abandoned by surrounding communities and simply used as garbage dumps. Meital described how the Bassatine cemetery was so covered in trash that 250 truckloads of garbage were removed before tombstones could be cleared and righted, gates to tombs reinstalled, paths cleaned and restored, and graves polished. However, not all has gone smoothly with that renovation.

A Jewish Geniza Discovered in 2022 Now Seems Lost to History

After forcing entry to a Cairo Jewish cemetery, Egyptian Antiquities Authority Authority piles bags filled with the contents of the Geniza onto a truck. Roi Kaisos, VIN News.

The renovation project at the Bassatine cemetery was originally inspired by Magda Haroun, one of handful of Egyptian Jews remaining in Cairo today and a staunch supporter of the preservation of Jewish history. The cleaning and restoration of the cemetery was approved by Egyptian authorities and paid for by American Jews and other sponsors. However, the authorities’ attitudes have not been entirely supportive.

In 2022, members of the Jewish community were working to clear the tons of old tires and rubbish from the Bassatine cemetery in Cairo when a Geniza – a buried storehouse of religious, family, and economic records – was discovered buried in the cemetery.

While the Jewish sponsors of the restoration have insisted that all finds from Jewish buildings and cemeteries will remain in Egypt, and only asked to be able to safely preserve them there, Egyptian authorities aggressively took possession of what appear to have been thousands of records in the buried Geniza.

As soon as the news of the Geniza’s discovery spread, the government’s Antiquities Authority broke through a cemetery wall and interrupted their removal by the Jewish community. The Jews present pleaded that at the least, a rabbi should oversee the dismantling of the relics of their community, but they were ignored. Government agents threw the records into 165 plastic sacks, loaded them onto trucks and took them away.

No access has been granted since. All information about when the records in this Geniza were made, their contents and the light they could shed on the historical community remains unknown. Sen. Gary Peters, a Michigan Democrat, has urged the Biden administration to protest the seizure of records that rightly belong to Egypt’s Jewish community. It is not known whether the U.S. State Department has made a serious effort to reclaim these records for Egypt’s tiny remaining Jewish community – or sought greater access for the world’s scholars. The Egyptian government has also remained silent on what has been done with this lost Geniza.

Additional Reading:

Plaque showing Moses Maimonides in the synagogue of Moses Maimonides (Moses ben-Maimon), Jewish quarter, el-Muski, Cairo, Egypt, Photo by Roland Unger,

27 February 2006

Plaque showing Moses Maimonides in the synagogue of Moses Maimonides (Moses ben-Maimon), Jewish quarter, el-Muski, Cairo, Egypt, Photo by Roland Unger,

27 February 2006